The South African

The South African

[KwaZulu-]Natal's involvement in the 1914-18 war provides an encompassing insight into South Africa's contribution to the conflict better known as the First World War. Durban, one of the Union's main ports, linked the territory with the campaigns in Africa, Europe and Asia as well as providing a link with Australia and New Zealand through ships passing by, while Pietermaritzburg, the then provincial administrative centre, brings the Home Front to the fore, not least with it hosting the main internee camp at Fort Napier. Other towns such as Dundee played their part through the provision of coal and other produce, however accounts of their involvement are scarce. What follows is an overview of the role Natal played in the Great War of 1914-1918. A summary article appears in The June 2021 Military History Journal.

Due to its coastal position, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) was put on alert on 31 July 1914 pending war being declared between Britain and Germany. When war was eventually declared on 4/5 August 1914 (time differences considering), the RNVR was called out to protect the harbours, a necessity as German ships were now enemy ships and could be impounded as spoils of war, but similarly could cause problems by relaying information back to Germany. The harbour, as with others around the Cape and Port Elizabeth, would play an important role in South Africa's contribution to the war, not least for revictualling troops and others in transit, but also for trade. That Britain was soon able to control the seas worked in the Empire's favour but also led to potential rivalries between constituent parts, significantly around shipping. For example, the issue of spying and sharing sensitive information impacting on national security would cause friction between the Union and Portugal. The Union government wanted to go through mail and goods on Portuguese ships destined for Portuguese East Africa as it believed the Portuguese, despite being allies of Britain, were supporting the Germans in the East African colony. However, Britain refused, thereby undermining the Union's attempts to ultimately occupy the Portuguese territory and harbours.1

On the outbreak of war, enemy ships were on the seas and in some cases in port loading or offloading goods. According to the rules of war captured ships became spoils of war and goods on neutral ships destined for enemy territories could be confiscated. However, complications set in when goods on enemy ships were destined for allied territories, such as Australia, and around who paid docking fees and other costs. Prize Courts were therefore set up to mediate the various interests, two of which sat in South Africa, one in Durban. During the first six months of 1915 for example, five cases were put before the Durban Prize Court which convened in terms of Section 12 of the Naval Prize Act, 1864. The cases concerned two German ships SS Surat and SS Gotsland, and three British ships, RMS Briton had lost its cargo to German agents, while the SS Glendhu had on board tubes and other cargo belonging to the German steamer Muanza which had been at Swakopmund. The last was the Guildford Castle also carrying German goods.2

Inland, on 6 August the South Staffordshire Regiment, on garrison duty since 1913, arrived back at Fort Napier from Potchefstroom where they had been undertaking their annual manoeuvres. The garrison forces, at Cape Town, Pretoria and Pietermaritzburg, had been retained in South Africa following the 1899-1902 war, initially to maintain peace between the previous warring factions, and after 1910 to support the new Union with maintaining internal order in case of black unrest. On 7 August, the South Staffordshires were granted leave pending further instruction, the Union government having informed the British Prime Minister that South Africa would look after its own defence thereby enabling the Imperial garrisons in Natal, Transvaal and the Cape to return to Britain to assist in the defence of the motherland. The garrison commander was Lieutenant Colonel Robert Montgomery Ovens (1868-1950), who went on to serve in Europe being wounded on 31 October 1914 at Gheluvelt (1st Ypres) in an encounter which saw 78 of the original battalion march out. Ovens survived to become a Brigadier General.3

While waiting further orders, the garrison entertained the local community with band performances and marches, no doubt providing a presence at the Patriotic gatherings in Pietermaritzburg on 8, 10 and 12 August, the garrison 'officially' leaving Fort Napier on the 12th after fittingly having played the 'Retreat' at the meeting that day. Their leaving would cause economic problems for the capital as they withdrew their savings from the banks. On the positive side, an auction of the regiment's furniture on 13 August raised £300.4 Despite ostensibly having left Fort Napier on 12 August, it is recorded that the South Staffordshires held their final regimental event on 17 August 1914 when the band played at the Town Hall. The actual date of departure was kept quiet for security reasons.5

It was not only the white inhabitants who held patriotic meetings and pledged their loyalty. On 17 August, the Indian community sent a declaration of loyalty to London and on 27 August the Natal Indian Association at a mass meeting promised to do their duty towards the Empire. The South African National Native Congress (SANNC, now ANC) which had formed in 1912 passed a resolution of loyalty on 22 August 1914 in Vryheid. At the time the President of the SANNC was Albert Luthuli (1898-1967) who although born in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, had close links with Natal, specifically Stanger (KwaDukuza), where he was employed.

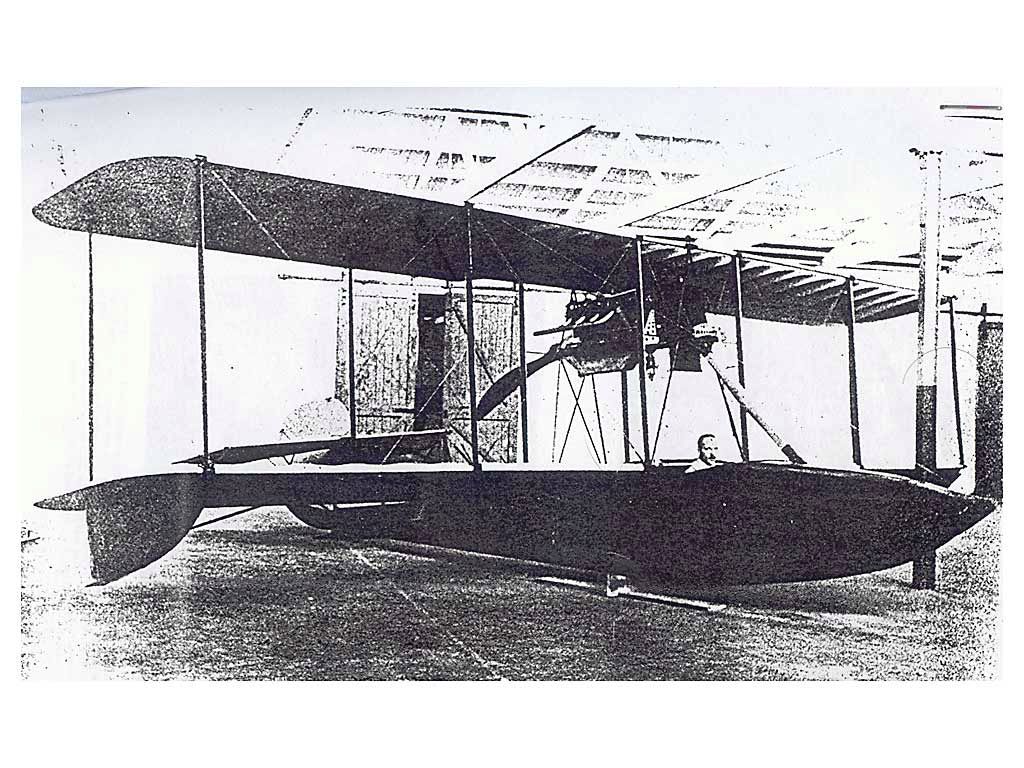

In Durban on 12 August, rumours were circulating about the presence of the German cruiser Königsberg which was reported seen 29km (18 miles) off the Durban coast. This resulted in a tightening up of harbour security due to an increased fear of spies, and greater plane reconnaissance. The Königsberg had been falsely sighted, but its taking refuge in the Rufigi (Rufiji) Delta in German East Africa (now Tanzania) from 20 September 1914 was to see a Durban resident, Dennis Cutler,6 called to East Africa to locate the ship. Cutler was an aviator flying short flights around Durban harbour in a Curtiss 90hp Flying Boat Type S.

Dennis Cutler in the Curtiss Type S

He and the aircraft, owned by Gerald Hudson,7 were duly sent north, Cutler being recruited into the RNVR to make this official. The plane went north on the Kinfaus Castle from Cape Town but had to call in at Durban to be repaired following damage caused by heavy weather. Why the plane had to go from Durban to Cape Town to return via Durban on route to East Africa has not yet been ascertained although it might have been that Cutler had to enlist and register the boat with the RNAS based in Simonstown. It had taken from September to November 1914 to get Cutler from the Union to East Africa.8 Meanwhile Cutler was taken prisoner in December 1914 when his plane crash landed; he was only released in November 1917. On 11 July 1915 the Königsberg was finally scuttled, making this the longest "naval engagement" of the war.

Meanwhile, the Imperial garrison having left, Fort Napier was standing empty. This provided a suitable space for German internees who were moved from Roberts Heights (Voortrekker Hoogte, now Thaba Tshwane) in Pretoria on 24 and 25 October 1914. Two thousand men marched through Pietermaritzburg with the local Defence Rifle Association, commanded by Colonel John Weighton,9 guarding the prisoners. Over time, other internees were brought to the camp, at its height a total of 2,500 being interned, including men from German South West Africa (Namibia). On 27 October, it was rumoured that there had been an attempted breakout from the camp. Colonel William Manning, South African Police,10 in command of the camp denied this but had asked for additional guards. It is said he received twenty times more than he asked for.11

Internees playing cards to while away the hours at Fort Napier

The following year, on 7 May 1915, the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine led to anti-German riots across the country, Durban and Pietermaritzburg shops and business being affected. Donald Davies identified that less than a week after the sinking - no doubt when the news arrived in South Africa - in Durban, within an hour on the evening of 13 May, Baumann's Bakery in Point Road, Gutten's Small Shop, Rand Hotel, Sea Breeze Hotel, Alexandra Hotel, Anchor bar had been targeted, with goods from some premises dragged out on the streets and burned. The burning continued with Rolfes, Niebel & Co in Cato Street and Smith Street, Liebermann & Belstedt in Mona Road, Mullers Wood Mart and Karl Gundelfinger's building. There were a couple of 'mistaken identity' incidents such as WH Muller & Co (Netherlands) being attacked. The Marines were called out to reinforce the Police. On Friday 14 May, the burning continued with St Cyprian's Church (Anglican), Heubner's Store, Eberhard, Bull & Oehmann, Orenstein - Arthur Koppel Ltd, Mr Liebermann's home on the Berea, Vogel's Sweet Shop, and Joisten's shop in West Street (which was saved) being attacked. Malcomesses, Buttery & Hutton, Korte Cabinetmakers, the German Club, Baumann's in West Street, Central Motors and Lowenthals followed. A breeze caused other buildings to catch fire. The following morning, Arabs Store (Turkish), the Sea Breeze and Beach Hotels continued, followed by the Hotel Oceanic, Berea Bar and Bartholomai Jewellery Shop in the afternoon and evening. On the Monday, a public meeting took place outside the Town Hall with resolutions of allegiance to the crown being passed. As a result, more German people were interned at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg.12 As with the earlier targeting of German residents, many of neutral Austria-Hungary and other European countries were mistakenly identified as being German. After the war, German and other enemy country born naturalised South Africans were excluded from accessing bursaries such as those started in 1916 by the Durban Municipality for students studying a BA or BSc in Pietermaritzburg.13

Internees gathered for a meeting at Fort Napier

On the military front, the Durban Light Infantry and Natal Carbineers had been mobilised on 8 August 1914 in readiness to act against a coastal invasion and to relieve the Imperial garrison. These two regiments together with others were to serve in German South West Africa (GSWA) and helped put down the 1914 rebellion, while individuals served with distinction. Back in August, on the 12th, Minister of War Jan Smuts had written to Sir Duncan McKenzie, the senior military officer in Natal, about the need for a contingency force to replace the Imperial garrison. It was hoped McKenzie would remain available to assist in Natal in case of disturbance by 'Natives or attacks at Durban.' Smuts wanted McKenzie's opinion on the matter and to recommend any commanding officers to serve with General Christian Frederick Beyers (1869-1915) in the proposed expeditionary force for GSWA with Durban-born Colonel John Robinson Royston (1860-1942) being entrusted with raising the Natal Volunteers.15 However, the units would only be able to serve outside of the Union once parliament gave permission which happened in early September when the new Governor General, Lord Buxton, arrived.

Recruitment for the various units took place locally after the regular regiments had been called up, with Jacobs camp being the Durban mustering point. This was likely to be the same ground previously used for the 1899-1902 concentration camp16 as large spaces and bespoke buildings tended to be reused as seen by Fort Napier and other locations in Cape Town (Richmond) and Johannesburg such as the showgrounds. Jacobs was also to include a labour camp for SANLC men going to East Africa and Europe, and probably also for those employed on the docks and in the other nearby camps. On 20 December 1917 the Cape Corps was sent home from East Africa. Six hundred of them were sent to Jacobs to be quarantined and to receive medical attention before being allowed a month's recuperative leave before heading to Egypt and the Middle East. They eventually sailed from Durban on the HMT Magdalena on 3 April 1918. On 18 September 1918 at the Battle of Square Hill in Palestine they suffered their greatest losses: 51 killed, 101 wounded and 1 captured.

Despite Smuts' desire that McKenzie remain in Natal, he commanded the 1st and 2nd Natal Carbineers during the rebellion and in GSWA, being recognised for his meritorious service in the latter campaign. The other unit under McKenzie's command was the Natal Field Artillery. McKenzie and the Natalians were involved in the attack on Gibeon in April 1915 where the German commander von Kleist was defeated but managed to get away. McKenzie lost three officers, 21 ordinary ranks killed and ten officers and 56 other ranks wounded against 11 Germans killed, 30 wounded and 188 prisoners as well as various ordnance captured. The force covered 322km (200 miles) in 12 days before the action. This was to be Natal's last involvement in the campaign and during May they all returned home.17 The commander of the Natal Light Horse, Royston was recognised for 'meritorious service' in the rebellion and GSWA. He had served with the Natal Mounted Rifles during the Zulu War, with the Imperial Light Horse in the 1899-1902 war, was involved in the siege of Ladysmith and after his service in GSWA in 1915, saw action in Egypt in 1916 when the South Africans earmarked for the Western Front were diverted to that theatre.

Botha's Natal Horse, totalling about 125 men, commanded by JJ Botha, a brother of the Natal-born Prime Minister Louis Botha, had three squadrons in the field. According to Captain Edward Sylvester Archer who was in command of A Squadron (the original Botha's Natal Horse), 'Served […] late Transvaal rebellion and German West Campayne [sic]. I was the originator and organiser of this Regiment which served through the Rebellion and GW Campayne to a finish. … My Squadron captured Tsumeb, my centre took the village, my right the three Guns on the hill, my left the position on left. This village held our prisoners who were in a barbed wire inclosure in a pittable condition and were released. This ended the GW Campayne.' Another entry has 'After the rebellion was quieted and a months furlough we marched to Kimberley in route to GW. Here we joined by the Barberton [Major Hazelden] and Sabie [Major McLaughlen] Commanders. This was suggested by the Defence Department so as to make our Regiment stronger for service in GW. The whole was termed Bothas Natal Horse which was three Squadrons.' On 1 June 1915 Burgher WP Richardson of Botha's Natal Horse, 3rd Mounted Brigade was captured whilst on patrol.18 The 3rd Natal Mounted Rifles19 was commanded by William Arnott, which first saw service in the Orange Free State during the rebellion, and the 4th Umvoti Rifles under Samuel Carter20 also formed part of JJ Botha's command.

The Durban Light Infantry Historian, Arthur Clive Martin (1892-1985), was surprised on arrival at Walfisch Bay to see the Durban tug Sir John in service.21 After his time in GSWA, he served in Europe and later in Tobruk during World War Two where he was taken prisoner in 1942. Lieutenant Colonels James Dick and Richard Leonard Goulding commanded the 1st and 2nd Durban Light Infantry respectively. They saw service in GSWA under Ben (Barend Daniel) Bouwer (1875-1938) and Percival Scott Beves (1868-1924). Colonel James Scott-Wylie (1861/2-1937) and Lieutenant Colonel George Mary Joseph Molyneux (1874 Ireland-1959 Durban) also served with 1st Durban Light Infantry during the war and went on to command the unit when it was involved in the 1922 Rand strike.22 At the end of May 1915 when the southern portion of the GSWA campaign was over, men of the 'railway company' of 2nd Durban Light Infantry were transferred to the newly formed Railway Regiment and South African Engineer Corps.23

The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, Durban fell under the command of the Senior Naval Officer at Simonstown, in 1914 Admiral King-Hall. It comprised the Natal and Cape Naval Volunteer units and on the outbreak of war totalled 12 officers and 276 ratings.24 It was into this unit that Dennis Cutler was recruited for service in East Africa.

The Durban Garrison Artillery manned four 15-pounder guns at Durban Bluff. The Garrison was made up of what had previously been the A and B Batteries of the Natal Field Artillery. They were supported by the Durban Coast Defence Force which was a reserve unit and provided engineering, signalling, telegraph and harbour support services. Men of the DGA were to join with others to form the South African Heavy Artillery Brigade under Lieutenant Colonel JM Rose, Royal Marine Artillery. DGA provided K Heavy Battery which accompanied Colonel Christian Anthony Lawson Berrangé's (1864-1922) Eastern Force in GSWA and N Heavy Battery which served with Northern Force under Beves. In 1918, the Bluff received two six-inch guns and two three-inch quick firing naval guns which were placed in new emplacements. The Garrison forces were to later serve in France25 and in East Africa as the 4th Battery Heavy Field Artillery. 'The guns were drawn by teams of six mules with Coloured and African drivers riding postillion.'26

Natal Carbineers arriving in Cape Town

at the end of the Namibian (German West Africa) Campaign

At the end of the German South West Africa campaign, the South African forces were demobilised as agreement had not yet been reached on future involvement in the war. Not long after, however, recruitment started for the Imperial Service Unit to be commanded by H Timson Lukin which saw service in Egypt and Europe and in November recruitment started for the East African Expeditionary Force. Both these units were paid for by Britain with the Union supplementing the pay. This was to overcome opposition by the anti-Empire National Party.

During this hiatus, in October 1915, Lieutenant Colonel Herbert of the Military Records Office, South African Expeditionary Force, approached Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener privately 'with regard to the desire of the Natal Carbineers, of which he is Colonel, to send some detachments over to serve with the affiliated Regiment, the 6th Dragoon Guards.' Pretoria did not approve, and the matter was referred to the Colonial Office. A letter was sent to Governor General Buxton to ascertain officially the Union's view.27 No reply is recorded in the file and it is unlikely the Union agreed given it was recruiting for East Africa at the time and had denied other similar requests by Aubrey Woolls-Sampson, Percy Fitzpatrick and Colonel Byron.28 Abe Bailey seems to be the only private individual in South Africa to have been granted permission to raise a contingent for Imperial service. Three of Bailey's Sharpshooters had Natal links:29 Lance Corporal Harold Potterill was a farmer born in Pietermaritzburg who served with the Hamburg Rifles and then Natal Carbineers. He was missing in action, declared dead on 8 April 1918. Bert Arthur Lowring although born in Walthamstow, UK, served with the South African Mounted Infantry and recorded his father in Durban as his next of kin. He was discharged in 1919 and later served in World War Two with the Durban Coastal Garrison. Garnet Evelyn Lugg was born in Greytown, Natal, and worked as a clerk in the Durban Law Courts before he signed up. He was discharged from the army in 1919.

Others went on to serve in German East Africa such as Molyneux who commanded 6th South African Infantry which saw action alongside 5th and 7th SAI as part of Beves' 2nd South African Infantry Brigade at Salaita Hill on 12 February 1916, the South Africans losing 138 men of the 172 lost that day. Another was Philip Davis of the Natal Witness. He was commissioned into the Natal Carbineers before the war, served in South West Africa, was ADC to Lieutenant Colonel DW Mackay of the 7th Mounted Brigade, and served in East Africa with the 8th South African Horse and later the South African Service Corps (Mechanical Transport). On his return to the paper in 1919 he became editor, retiring in 1939 'after twenty years at the helm', ending an '87 year long dynasty'.31

While most units from South Africa serving in East Africa were composite with the initial recruitment being provincial, one unit was completely provincial from Natal. This was the Indian Bearer Corps consisting of 500 men of whom 17 lost their lives and 92 suffered long term health issues. The corps was founded along the same principles as Gandhi's 1899-1902 Stretcher Bearer Corps. A camp was set up for them on Stamford Hill Road and were trained by Captain Dunning who had Indian Army experience. The first group comprising 88 Tamalians and 26 Calcutias left Durban on 13 December 1915 for East Africa where they were split between Captain Briscoe of the South African Horse and General van Deventer. The second corps served under Captain Murdock. On Christmas Day 1916 and 27 January 1917 respectively 51 and 41 bearers returned. Of the total who served, 10 died in 1916, 10 in 1917 and three in 1918. They were demobilised in March 1918.32

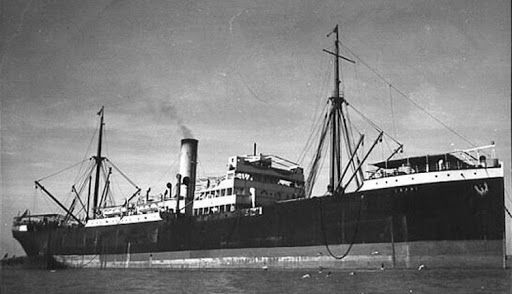

Ostensibly the hospital ship Ebani was staffed by the Natal Medical Corps and which saw service between 13 August 1915 and 12 October 1919.33 Prior to this, the Natal Medical Corps had served in German South West forming the 6th Stationary Hospital at Swakopmund, with the Ebani. It could care for between 300 and 400 patients. Lieutenant Donald McCauley was Officer Commanding the Hospital Ship which travelled over 200,000 miles and treated 50,000 sick and wounded during its commission.34 Three members of Ebani were recommended for 'valuable services rendered' between 1 August 1918 and the end of the war: Chief Officer A Downs, Master Mariner A Faill, Chief Engineer W Lumsden. Faill was also recognised, together with Downs, for 'excellent services rendered' between 1 December 1917 and 31 July 1918. While not from Natal but rather Hermanus, Pte Edward Edmond Williams who served on Ebani is buried in Brookwood Military Cemetery having been killed accidentally on 20 May 1919 when he '[fell] down a hold on the Hospital Ship Elbani [sic], which was in dock for repairs. The hatchway, it was stated had been negligently left open by workmen.'36

The Hospital ship Ebani which was

medically staffed from Natal

While the medical staff were of the Natal Medical Corps, a perusal of the Ebani crew listing for 1915 suggests few were from Natal, only one name being identified: Steward Ernest Denby French, age 30, with previous service on the Goorkba. A few others were from Cape Town and Barberton while most were from other territories, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Seychelles amongst others.37 Dr Dugald Campbell Watt, the brother of Cabinet Minister and Natal Representative Thomas Watt (1857-1947), sailed on the Hospital Ship Ebani from 7 August 1915 to the 15th when he disembarked in Cape Town for return by train to Pietermaritzburg.38 Dr Kenah Murray of the Molteno family recorded that in May at Walfish Bay he met Campbell Watt and a section of his hospital who was in charge of a clearing hospital in German South West Africa. He had been there for two months, that is since January. Later, on 6 March 1915 Watt and Murray again met up in Swakopmund.39

Natalians served elsewhere in the war too. Natal University College saw 77 students or ex-students volunteer, of whom two were awarded Distinguished Flying Conduct medals and six Military Crosses while 13 were killed including Second Lieutenant (Acting Adjutant) Erroll Victor Tatham who was killed on 18 July 1916 at Delville Wood. His death was the same day as his cousin Second Lieutenant Russell Pears Tatham. Three days earlier Erroll's brother, William Inglis (Boy) Tatham, was killed at sea in the Bay of Kotor, Montenegro when the submarine he was on H3 was sunk by a mine. It is suggested he was the first South African submariner to lose his life.40 As a result of these and other enlistments, the college saw numbers decline from 72 in 1913 to 33 in 1915 with a slight increase to 36 in 1916. Few who left during this time completed their degrees. As a result, the entry age was reduced which saw an increase in student numbers in 1918, of whom a large number were women.41

While Britain had its Pals Battalions, it appears that South Africa had its equivalent given the Natal University College and Dundee High School account of the war. Apart from the Tatham deaths mentioned above, there was another Tatham who served in and survived the war, namely Sidney Mortimore Tatham, cousin of Russell. He broke his military service to get married on 9 July 1917, and settled in Pietermaritzburg on his safe return in November 1920, dying in the Cape in September 1938.42 Another Dundee school boy was Garnet George Green who was awarded the Military Cross. He had held Delville Wood with 118 men against three German divisions, served in GSWA and Egypt before being killed at Arras on 23 March 1918.43 This school link, particularly strong in Natal was the result of the Cadet system which had been introduced in 1909 eventually becoming compulsory. In 1908 there were 3,277 Cadets across 57 School Corps. As with the Pals Battalions, there was a camaraderie and ethos among the boys which led them to enlist. Hilton outside Pietermaritzburg saw 371 old boys enlist of whom 47 were killed while College had 91 old boys die in the war.44 The Rector of Michaelhouse in summing up why so many enlisted, captured the sentiment Kitchener had tried to espouse in encouraging cadet corps: 'Boys leave this school with a taste for military work.'45 Mr AJ Turton of Dundee High School recalled that in the early days the school cadets looked like soldiers of the French Foreign Legion. "Suspended from the back of their kepis were the white linen spine protectors made famous by the Foreign Legion. We later changed to the New Zealand type broad-brimmed hat turned up at one side without the spine protector."46

While it has not yet been possible to know exactly how many Natalians served in the war, there is greater clarity over the number who died, with the names of 629 men and women being recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves catalogue as being from Natal. A sample of firsts and lasts confirms the extent of Natal, and South Africa's, involvement in the conflict. What obscures the figures to an extent are the unknowns such as one of the last recorded deaths being Corporal 1630 Gysbert Johannes Roos of 3 SAMR. He died on 31 December 1920 and is commemorated in the South African Book of Remembrance. We know he was from Natal as the additional information on the CWGC website records 'Husband of Louisa Christina Catherina Roos, of Vryheid, Natal', yet this level of detail is not available for all dead recorded on the database.47

The earliest death is recorded as Reginald Gordon Hindson, Royal Field Artillery on 13 September 1914. He is buried in Carlisle (Dalston Road) Cemetery. He was a medical student at Edinburgh University and his parents were in Nonoli Peak, Kearsney, Natal. It is not clear what he died from, likely disease as he was still in the UK.

Rifleman 2501 George Jenkin Waters, 1 South African Mounted Rifles was the first Natal related death recorded in German South West Africa on 26 September 1914. He is buried at Warmbad (Belo Belo). His parents were of Church Street, Pietermaritzburg. Trooper 268 William George Furner of the Natal Carbineers died on 25 January 1914 and is buried in Upington.

The first death in Europe was Second Lieutenant James Reginald Shippey, 4th (attached 1st) Battalion Bedfordshire Regiment who died on 14 October 1914. He is buried in Bethune Town Cemetery in France. The last death in Europe recorded is that of Flying Officer Stephen Percival Marcus of 6th Flying Training School who died on 15 August 1921 and is buried at East Sheen Cemetery. He was born at Tongaat although his parents were living in Berea, Durban.

Captain Edward Kenelm Bird of Pietermaritzburg was one of the last Natal linked men to die in the war on 27 September 1919. He is commemorated on the Cairo War Memorial Cemetery having served with the 29th Punjabis attached 20th Duke of Cambridge's Own Infantry (Brownlow's Punjabis).

The last Cape Corps soldier to die was Corporal 1093 Thomas Joseph Knipe of 1 Cape Corps on 12 August 1919. He is buried in Alexandria (Hadra) War Memorial Cemetery. His parents were in Pietermaritzburg while his wife was in Kearsney, Stanger.

Lieutenant Cecil Francis R Bland of 3 Royal Berkshire Regiment died on 7 July 1919 and is commemorated at Archangel Allied Cemetery where he had been serving against the Red Army. He was born in Durban and was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palms (France) and the Military Cross.

Company Sergeant Major 12229 Percy William Pryce of the Military Labour Corps died on 16 May 1919 and is buried in Cape Town (Plumstead) Cemetery. Although from Arundel, Sussex, he had served in the 1906 uprising and had been attached to the Rufigi River Transport and Transvaal Horse Artillery.

Lieutenant James George MacLennan of the South African Service Corps died 20 April 1919 and is buried in Mombasa (Mbaraki) Cemetery in Kenya. He was born at Inverness but was resident in Pietermaritzburg where he left a wife.

The last recorded female death was Nursing Sister Hilda Maude Bettle of the South African Military Nursing Service who died on 27 February 1919 and is buried in Zomba Town Cemetery in Malawi. Her husband Lieutenant JS Bettle served with 1/1 King's African Rifles having served four years of which three and a half were in East Africa. They were from Durban. Three other nurses from Natal lost their lives in the war too: Annie Winifred Munro of Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg on 6 April 1917 Constance Addison on 12 September 1918 and Edith Agnes Baker on 6 November 1918. Gertrude Eliza Dunn of the South African Nursing Service born in Yorkshire is buried in Durban (Stellawood) Cemetery having died on 14 December 1918. Other Natal linked women who served with QAIMNS have not been included in this analysis as the search returned 'nil records'.

Some, but not all deaths were recorded in the press. For example, Driver Granville Davies who died of pneumonia in April 1917. EJ Hennesey - East African Mounted Rifles, ex Natal, died on 3 September 1915, JH Roberts of 6 South African Horse, Natal and Fred Stott, Royal Naval Reserve, died 11 December 1918 were all reported in the Natal Witness of 25 December 1918.

Of the 4,159 First World War dead buried in South Africa, 374 are in 23 cemeteries in Natal. The greatest number of burials are at Durban (Stellawood) - 196 burials; Durban (Ordnance Road) Military Cemetery - 81 burials and Pietermaritzburg (Commercial Road) - 54; Durban (West Street) - 12; Pietermaritzburg (Town Hill) - 6; Durban (Stamford Hill) - 4; Dundee - 3; Kokstad and Ladysmith - 2 each and the remaining cemeteries with one burial each.48 While most buried at Stellawood are South African, there are significant numbers of Nigerians, Gold Coast (Ghana) and Royal Navy including two German Navy. Not all who died in Durban though are buried or recorded on the CWGC listing. For example Charles Richardson Hird of Ulverston, Captain of HMS Moorland, a merchant navy vessel died on 2 December 1917. His place of death is recorded as Durban Hospital and the death certificate suggests he was buried at Stellawood. However, an on the ground search of Stellawood and its registers do not have any reference to his burial. He may well have been buried at sea. Until his death can be proven to be war related, he will not feature on the CWGC listing.49

Sister Catherine Decima Dick of the South African Military Nursing Service (SAMNS) who served in the 1899-1902 war, GSWA and France died in Pietermaritzburg in 1931. She played an instrumental role in setting up the SAMNS.50

Not all was bad news, Sister Alexina Donald, Acting Matron Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service at the Kaiserhof Hotel which became General Hospital 2 married WC Donald becoming the grandparents of Donald Davies of Natal.51

Many of those buried in South Africa had been in military hospitals either on route somewhere or on arrival back home. Natal had a number of hospitals, convalescent camps and homes. The following list is from the Official History: The Union of South Africa and the Great War 1914-1918.

No 3 General Hospital, Addington, Durban was on the sea front adjoining the Durban General Hospital. Although it was planned for 1,700 beds, it only managed 510 Ordinary patients, 93 venereal disease patients and 10 Isolation. They took over the school building which found a replacement at Rinkoscope. The school eventually returned in July 1918.52

No 3 General Hospital - Drill Hall Section was the property of the Durban Light Infantry which was used as hospital accommodation.

Pietermaritzburg Military Convalescent Hospital In the grounds of University College, Pietermaritzburg about one mile outside the city centre. It provided accommodation for 388 patients but could take one thousand if needed.

Jacob's Camp, Native Convalescent Camp catered for labour from East Africa in particular those suffering from malaria. It was four miles from Durban and adjoined the Native Military Hospital. It cared for 480 patients. In May 1918 it was partially closed and patients moved to Native Orderlies Quarters, Addington Military Hospital.53

Ocean Beach, Imperial Rest Camp [Marine Parade] housed troops on route under canvas. It catered for 3,000 officers and men but was later increased to accommodate 5,000.

Ocean Beach, military convalescent Hospital, Durban was on Durban beach. It had previously been the Imperial Rest Camp, which was moved to Congella [King Edward Hospital] and accommodated 504 patients.

The Internees from Fort Napier suffering from enteric and typhoid were housed in the grounds of Grey's Hospital. The nurses did not want to treat the sixteen admitted, of whom one died. They were accommodated in three tents between February and May 1918.54

Not all who passed through Durban were ill or in need of medical attention. The vast majority were in transit, with a stop over of a day or longer pending onward movement. A number have left recollections of their experiences of Durban and its environs. Some enjoyed it so much, they tried to stay.

A General Depot was set up at Congella 'further up the harbour'55 which saw local labour employed. Men on route stopped off at camps in Congella whilst officers were housed in Pietermaritzburg and Durban. In December 1917, a court martial was to take place concerning 8th Cheshire Regiment Albert Charles Amsler's desertion from the camp at Congella whilst stopping off on route India. He had failed to report on 17 November, the day the unit was to sail. Having missed the boat, he was placed under arrest until his trial being found guilty and sentenced to one year detention. The sentence was confirmed on 21 December 1917 by the Base Commander. He arrived in Bombay on 23 January 1918 and was hospitalised, eventually dying on 18 October 1918 at Secunderabad of influenza, having seen little military action due to regular stays in hospital.56

CM Smith of Brisbane in his diary recorded on 28 February 1917 that he 'Arrived in Durban today at 8 am. The sight of land was a welcome one after three weeks of nothing but water around us. A tug called the "Harry Escombe" took us in past the breakwater and over the bar [… having moored] we were - about 1500 of us - then taken for a dusty and dirty route march to the beach through coal dust and snad and returned at 12.30 pm when we had dinner. We were paraded again, boarded the tug which piloted the Troopship in, and ferried by it to the opposite side of the bay on which side the City lays, marched to the Town Hall, about 3¾ miles away, and there dismissed. The YMCA have a hut just opposite […] Most particularly noticeable in Durban to a visitor were the great width of the streets, the number of coloured people in evidence (seemingly greater than the white), the number of Richshas, the scarcity of motor cars, and the sturdy well built Zulu police. We were well catered for, the trams being free and admission to the Zoological Gardens free.'57

Another, EG Moore, wrote, 'An interesting memory was the circular pier. It had wire netting to keep sharks out, and bathing took place within its perimeter. Fair enough, but what was most amazing was that the semicircle was divided in two by a fence of the same wire netting - segregating the sexes while bathing!'58

While many enlisted serving outside the Union, others provided services in country - managing camps, transport, recruitment, supplies of food, equipment and ordnance, and undertaking various administrative duties. Others did not enlist, remaining in their posts as educators, manufacturers, medical and veterinary practitioners which kept the country and economy functioning. While some objected to the war as seen most graphically by the 1914 rebellion, others did so less visibly. Of those remaining, many got involved in fundraising events as AJ Turton of Dundee High School recalled. 'In 1916 and 1917,the school decided to contribute to war funds and put on Gilbert and Sullivan's operettas H M S Pinafore, Iolanthe and The Pirates of Penzance. We played to packed houses in Dundee, Newcastle and Ladysmith. Extra shows were given beyond the advertised days. We had succeeded beyond our wildest expectations.' A Mr Gray wrote that 'When the First World War broke out, proceeds went to War Funds, so doing its "bit" was no small consideration with all of us.'59 There was fundraising for the Governor General's Fund, Red Cross Society through various committees. The Women's Patriotic League, Indian Women's War Relief Committee and the East African Comforts Committee all played their part in raising funds and organising and sending comforts to the men in the various theatres of conflict.

With men having left their jobs to enlist, there were vacancies left in the Union which needed to be filled to ensure society functioned. In 1914, the Women's Municipal Franchise Ordinance was passed allowing Mrs SA Woods to be voted into local office in Pietermaritzburg in 191560 and in 1917 the first two Women Police Constables were appointed as an experiment.61

Others did their bit as part of their daily lives. In late October 1917 Durban experienced excessive rains causing the Umgeni (uMngeni) River to flood its banks. On 28 October 400 men from the Springfield Flats (Tintown) area of Durban lost their lives, however 176 men were saved from drowning by the work of six men who became known as the Padavatan Six.62 This civilian act of bravery brings to light that, as yet, little if anything has been found in military memoirs to date of the natural environmental factors that affected South Africa.63 The influenza outbreak at the end of the war in 1919 accounted for 362 whites, 1,937 Indians/coloureds, and 11,663 blacks in Natal, Julie Dyer suggesting that 34 per cent of Pietermaritzburg's citizens were affected which had a knock on effect on local business.64 This compared with an estimated 139,471 persons across the Union of whom 11,726 were white and 127,746 'coloured' who 'died of influenza, pneumonia and broncho-pneumonia between 1 August and 30 November 1918'.65

The guns in Western Europe ceased firing on 11 November 1918 at 11am, the day becoming a recognised day of remembrance, especially across the Commonwealth. In addition to the usual 11 November remembrance services, Natal has an additional commemoration event, which few realise. This is the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg. It was started by Vic Clapham (1886-1962)66 who had served in the East Africa campaign who sought a fitting way to remember comrades who had fallen during the gruelling months they spent in that theatre, covering 1,700 miles. The race which covers 89km (55 miles) was first run on 24 May 1921.

Natal which according to the 1911 census had a population of 1,194,043 (98,114 or 8.2 per cent whites), saw 2,912 Active Citizens Force and 993 Veteran Reservists serve between 4 August 1914 and 24 August 1915. Although figures for Natal itself are not available, it was estimated in 1916 that the following numbers served voluntarily in addition to the Imperial Contingents: 11,900 overseas in East Africa, 3,000 in the SWA Garrison and 7,500 independently in British regiments.67

The 500 Indian Bearer Corps were from a population of 133,420 or 11.2 per cent. Of the 953,398 or 79.8 per cent black or Zulu population, very few served in the labour corps, the total Union labour contribution being around 25,000.68 Apart from the general reluctance to serve, there was the added reluctance caused by the government's handling of the 1906 uprising, Grundlingh noting that amongst the Zulu peasant community in rural Natal there were pro-German sympathies. Both Pietermaritzburg and Dundee having prophets predicting that the Germans 'would restore the land to their rightful African owners'.69

This has been a brief overview of Natal's involvement in the Great War of 1914-1918. There is, as the various references used indicate, much more which can be discerned if one takes the time to explore. What this article has hopefully shown is how local history can be international history.70

Footnotes

10 Manning was made a Commander of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the Bath for his work commanding the camp, London Gazette, 27 June 1919 p8090

11 Graham Dominy, 'Pietermaritzburg's Imperial Postscript: Fort Napier from 1910 to 1925' in Natalia 19 (1989). For more on Fort Napier and German internment see Stefan Manz and Panikos Panayi, enemies in the Empire: Civilian Internment in the British Empire during the First World War, Oxford University Press, 2020

12 https://www.genza.org.za/index.php/af/takke/durban-en-kus-tak/701-durban-aflame-the-burning-of-german-1915

13 http://www.natalia.org.za/Files/Publications/Stella%20Aurorae.pdf p55

14 Anne Samson, South Africa mobilises: The first five months of war, in Scientia Militaria Special edition, 2016

15 Hancock and vd Poel 3, pp188-9, letter from Smuts to McKenzie, 12 August 1914

16 http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/thread/voortrekker-concentration-camp-memorial-jacobs-durban

17 JJ Collyer, German South West Africa campaign, reprint

18 Great War Forum - In search of Botha's Natal Horse. Others who served in the unit included: Private George Grahame, Captain Will van Rooyen, Dr Captain Briscoe, Lieutenants Wallie Meek, B Faulie, Capt Payne who was killed in German East Africa. Captains Spiers, Currie, Lieuts McDonnell, Lloyd, Ronnie McLaughlen, Thorpe, Prinsloo, Theodore Strassberg from the Greytown, Dundee or Newcastle areas

19 See SAMHS KwaZulu-Natal Branch newsletter No 383, October 2007 for brief overview of 3NMR

20 DNW Auction 24 February 2016

21 AC Martin, Durban Light Infantry 1854-1934, vol. 1. Durban: Headquarter Board of Durban Light Infantry, 1969

22 https://www.facebook.com/IMFA.Page/posts/imfa-mystery-address-contest-continues-this-is-a-long-one-but-bear-w-us-as-its-i/1124147914338485/

23 Durban Light Infantry, Vol. I, pp. 192, 195 in Salute the Sappers, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/UN/SouthAfrica/Sappers-I/Sappers-1.html

24 Ian van der Waag, A military history of modern South Africa,

25 Deon Fourie, 'The South African Corps of Marines,' in SAMH Journal, 1:1, December 1967

26 LA Crook, 'Ubique, The Gunners of South Africa,' in Scientia Militaria, 13:3, 1983, p70

27 TNA: CO 616/47 50988 Desire of Natal Carbineers to serve with 6th Dragoon Guards

28 Anne Samson, 'South Africa mobilises'

29 William Endley, South Africa at war: The Union Defence Force in World War One, GWAA, 2020

30 Charles Hordern, Military operations East Africa, vol 1, 1942

31 The Natal Witness, Open Testimony: An introduction to The Natal Witness South Africa's Oldest Newspaper

32 GoolamVahed, 'Give till it hurts': Durban's Indians and the First World War' in Journal of Natal and Zulu History 19:1

33 A record of his service is held at the Cory Library, Grahamstown

34 https://wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/greatwar-day-by-day/viewday.php?day=&mth=August&year=

35 London Gazette 7th supplement 5 June 1919 Number 31387; London Gazette 9th supplement 31 January 1919 Number 31156

36 www.ramc-ww1.com

37 https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/651505.html;

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/651506.html;

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/651507.html;

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/651508.html

38 Cory Library: Campbell Watts papers diary entries. Campbell (1858-1940) and Thomas Watt were born in Glasgow, emigrating to Pietermaritzburg in 1889 and 1883 respectively where Campbell qualified as a doctor in 1901 and Thomas as a lawyer. Both served in the 1899-1902 war. [Keith Hancock and Jean van der Poel, Selections from the Smuts papers, vol 3, p397 for Thomas; Biographical Database of Southern African Science (s2a3.org.za) for Campbell]

39 Chronicle of the Molteno Family, 2 August 1915 [https://www.moltenofamily.net/stories-and-history/chronicle-of-the-family/chronicle-of-the-family-1913-1920-table-of-contents/]

40 Tatham Family History, www.saxonlodge.net/getperson.php?personID=10807&tree=Tatham

41 Bill Guest, Stella Aurorae: A history of the South African University volume 1 Natal University College (1909-1949), Natal Society Foundation Pietermaritzburg, 2015 online:

http://www.natalia.org.za/Files/Publications/Stella%20Aurorae.pdf p51

42 Kevin Burge, StrenusArduaCedunt: A History of Dundee High School, Orange Grove Books, 2018, online: https://www.talana.co.za/images/2018/Dundee_High_School.pdf [27

43 http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/last-man-walk-out-delville-wood-was-dundee-man

44 Robert Morrell, From boys to gentlemen: Settler masculinity in colonial Natal, 1770-1920, UNISA, 2001,pp151-2

45 Robert Morrell, From boys to gentlemen,p152

46 Kevin Burge, StrenusArduaCedunt: A History of Dundee High School, Orange Grove Books, 2018, online: https://www.talana.co.za/images/2018/Dundee_High_School.pdf p59

47 https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/75463437/GYSBERT%20JOHANNES%20ROOS/

48 Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery search

49 South African War Graves project - author's assistance in researching the case

50 Lucy London and SANDF Doc Centre

51 Donald Davies talk, SAMHS Newsletter 460 KZN July 2014. WC and Alexina were Donald's grandparents.

52 SANA: GG 674 9/93/172 - No 3 General Hospital, Addington, Durban

53 https://kznpr.co.za/durban-addington-old-military-hospital-nursing-home/

54 https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Greys-hospital-1910_fig1_287764503

55 http://www.scotlandswar.co.uk/pdf_Cairnie_Great_War_Diary.pdf 13 Nov 1917

56 Durham University Roll of Honour, https://www.dur.ac.uk/library/asc/roll/register/

57 AWM2018.19.89 - Auto Diary of Charles Malcolm Smith, 1916-1918 Book No 1 orinal, available on line at https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/AWM2018.19.89

58 WG Moore, Early Bird, Putnam (1963) p85

59 Kevin Burge, StrenusArduaCedunt: A History of Dundee High School, Orange Grove Books, 2018, online:

https://www.talana.co.za/images/2018/Dundee_High_School.pdf p48

60 Julie Dyer, Health in Pietermaritzburg (1838-2008), p18

61 PS Thompson, 'The Natal home front in the Great War'

62 The Padavatan Six and the 1917 Natal Floods,

https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/padavatan-six-and-1917-natal-floods

63 Anne Samson & Melvin £ Page, 'Food and Nutrition' in Enclyclopedia 1914-1918, 2020

64 Julie Dyer, Health in Pietermaritzburg (1838-2008): A history of urbanisation and disease in an African city, Natal Society Foundation, 2012, p18

65 PS Thompson, 'The Natal home front in the Great War'

66 Vic Clapham was discharged on 7 July 1917 having been returned home from German East Africa where his health had suffered. During World War Two he served with the South African Harbours and Railways Division. Anne Lehmkhul, Comrades Marathon History, Bygones and Byways, 2012,

https://bygonesandbyways.blogspot.com/2012/05/

67 Thomas Boydell, 8 April 1916 Cape Town. Reported by Reuters

68 Anri Delport, 'South African Troops in Europe and the Middle East Union of South Africa' in Encyclopedia 1914-1918, 2017

69 Albert Grundlingh, Black men in a white man's war: the impact of the First World War in African Studies Seminar Paper, August 1982

70 Thanks to David Killingray for this insight

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page