The South African

The South African

Published on the Website of the South African Military History Society in the interest of research into military history

National Memory and Selective Forgetting

Forgotten men of the Indian Army left their imprint in Observatory, Johannesburg, during the early 1900s. Although their story has been largely forgotten and lost to public memory, a monument at the summit of Observatory Ridge1 honours their memory. This Indian Monument stands as a memorial to Indians who fell in the Anglo-Boer War South African War of 1899-1902, overlooking the valley where Indians served at a remount depot during the War. Erected soon after the end of hostilities, the Indian War Memorial was launched in the first flush of peace amidst a wave of enthusiasm and fanfare. Public interest and understanding of the monument then dissipated over much of the Twentieth Century.

More recently, the rise of revisionist accounts of the War has seen more inclusive representations of the conflict coming to the fore. Commemorations to mark the centenary of the Anglo-Boer War, held in 1999 – 2002, brought a flurry of publications and public events in which the experiences of black people in the War, having long been ignored and suppressed, were highlighted as never before. Yet this first ‘inclusive’ anniversary failed to raise the public profile of the Indian Monument, or to recover its meaning and significance.

The War Memorial takes the form of an obelisk of sandstone cut from the hill on which it stands. A tablet on the monument’s east side bears the inscription:

Figure 1: Johannesburg’s first war memorial:

the Indian Monument dates from 1902.

Photograph: Doke, J.

M.K. Gandhi: an Indian patriot in South Africa.

London Indian Chronicle, 1909.

Figure 2: The Indian Monument on Observatory Ridge in 2009

Photograph: Clive Hassall

Indians in the Boer War

These Indian men, although fully-fledged troops of the Indian Army, were ordered to act in an ostensibly non-combatant role during the Anglo-Boer War, serving as “auxiliaries” or “followers”. The Johannesburg memorial raised in their honour has been noted as the only monument to non-combatants under military service who fell on foreign soil in this region (Brink and Krige 1999, p 406). To the north, the monument overlooks the valley where Indians set up camp during the war, and where a group of their comrades were buried in the aftermath of the conflict.

Elsewhere however, in the standard works and official histories issued after the war, the enormous contribution of “Native”men of the Indian Army – men drawn from indigenous peoples of India - to the British war effort in South Africa is largely ignored. More recent histories have continued to tread these well-worn paths. The traditional view is, for example, echoed in a dictionary of the Boer War published in 1999 (Barker , p. 68-9). Under the entry for ‘Indians in the War’ the dictionary states: “Apart from the Indian Stretcher-Bearer Corps [consisting of volunteers from Natal led by M.K. Gandhi], there is no record of Indians having participated in the war as a group”. The author concedes only that “a few Indian officers of the Indian Army accompanied the British Army as observers but did not serve as combatants”.

As the Indian subcontinent2 was under British Rule, regiments of the British Army provided a garrison there alongside the Indian Army from 1858. Although no Indian Army regiments took part in the Anglo-Boer War, volunteers from these regiments, referred to as “Indian Army auxiliaries”, participated in supportive roles. The regiments from the Indian subcontinent that were sent to fight in the Anglo-Boer War were regular (permanent) regiments of the British Army stationed in India.

Whereas little information has been made known in South Africa of the role of the Indian Army auxilaries during the Anglo-Boer War, the distinguished service of Gandhi and his Natal Indian ambulance Corps has, by comparison, attracted much attention. Gandhi’s Ambulance Corps was, however, disbanded early in the war – at the end of February 1900 – when the British were able to take the offensive with large reinforcements and relieve the siege of Ladysmith3. The Natal Indian Ambulance Corps numbering 1 100 men served for only two months, whereas the Indian Army auxiliaries were far greater in number and many served throughout the war.

The centenary of the Anglo-Boer War was the first major heritage commemoration in South Africa since the advent of democracy in 1994. For the ANC government, this was an opportunity to foster inter-racial unity and reconciliation (Dominy and Callinicos 1999). One way of furthering this objective was to emphasise the shared involvement and suffering of Africans and Afrikaners in the War. Efforts at recovering African participation took centre- stage in a new ‘inclusive’ nationalist project to reconstruct a “South African War that belonged to all. For the first time, Africans’ war-time experiences as family retainers, auxiliaries, soldiers and concentration camp victims were recognised in commemorations, exhibitions and new popular histories.

For all the many tours, events and celebrations held across the country, there was relatively little to recall the Indian contribution in the War. As part of this nation-building centenary, not a single commemoration was held at the Indian Monument. Predictably, a number of tour operators revived the familiar figure of Gandhi. As expressed by Witz , Minkley and Rasool (1999, p. 372):

“Under the heading, ‘Indian Participation in the War’, the organisers of the centenary are also able to find a person of prominence to include in the war pantheon alongside Winston Churchill, Paul Kruger, Baden Powell and Jan Smuts: the stretcher-bearer and spokesperson for the Indian merchant elite, Mohandas Gandhi …”

The International Contingents

Far from being a purely South African conflict, the war of 1899-1902 soon became an international encounter, involving Canadians, Russians, Americans, Swedes and others. For all that, British troops drawn from the garrisons in India were greater in number than those of the foreign contingents from colonies such as Canada, Australia or New Zealand, with only the British homeland supplying more troops than India. Reinforcements from other British colonies or dominions comprised a combined total of 30 328 officers and men and 337 219 from Britain itself (Grant 1910).

The garrisons in India contributed 17 950 British NCOS and men together with 584 officers (or a total of 18 534) (ibid.), not counting the large numbers of Native auxiliaries who were deployed to assist them in South Africa. Despite reluctance to use Natives of India at the beginning of the campaign, by the end of the war large numbers of these troops had been deployed in all theatres of the conflict, in Natal, the Orange Free State, and above all the Transvaal.

Many accounts have been published on the role of contingents from Australia, Canada and other countries that took part in the Anglo-Boer War. Their sacrifices have inspired war memorials scattered throughout the world. Comparatively little research has however appeared on the Indian contingent which was the first to arrive after the outbreak of the war and became the largest of all the foreign forces brought in to reinforce the British garrison in South Africa. In general, the role of the Native Indian component of the Indian Army has often been neglected by researchers4. The Indian scholar Dr. T. G. Ramamurthi is however a notable exception, producing a little-known pioneering study (1996).

As detailed by Ramamurthi, by the time hostilities ended thousands of Indian soldiers were deployed South Africa in ostensibly non-combatant roles. Even though the War Office insisted and the Government of India faithfully instructed the Quarter-Master-General in India that there should be “no Native followers”, the first contingent sent out from India, and which arrived in Natal in early October 1899, included over 1 000 Natives. These included commissariat staff, veterinary and field hospital staff, as well as tindals and lascars of the Indian Ordinance Field Park.

According to a telegram dated 30 August 1899 from the Viceroy to the Secretary of State for India, the Indian contingent consisted of 5 635 British officers and men, 1 078 Natives, 2 334 horses and 611 mules and ponies. Most of the Indians were hospital workers, the Viceroy noted, though they also included grooms and private servants. The Indian contingent brought with it medical units, with three complete field hospitals for British troops and one field hospital for their Indian followers.

Black Contributions in the War

Despite the reluctance of the British War Office to acknowledge the involvement of “Natives” (Indians) in what was officially to be a “White Man’s War,” over 3 000 Indian troops including NCOs were in South Africa on war duty by April 1900. According to a footnote in the Times History of the War in South Africa, India supplied over 7 000 non-combatants in the course of the war.

From the outbreak of the conflict, the two protagonists, the Boers and the British, claimed this as a “White Mans’ War”. For many decades afterwards, historians cultivated the myth that the war was exclusively a white affair. This tide began to turn around the 1980s when Peter Warwick (1983) and others began to show how all sectors of the population were touched by the War. The focus of this wave of research has been to recover the African (and to a lesser extent Coloured South African) experience of the war.

The Indian auxiliaries shared the fate of other “Non-Whites” who were drawn into the conflict, but whose contribution was ignored for many years. About 11 000 African and Coloured servants accompanied the Boer commandos, playing a role similar to that of the Indian auxiliaries, carrying out such tasks as looking after horses, cooking and guarding ammunition (Labuschagne 1999). It is only in more recent years that the role has been brought to light of these so-called Agterryers (mounted grooms or attendants) and other black participants who served on both the Boer and British sides. However, even such belated recognition has, for the most part, been denied to their Indian counterparts.

In the case of African involvement, few traces exist in the form of monuments or memorial from the past – an absence which did much to erase this aspect from public memory. In part, this absence is rooted in the nature of the society in which Africans found themselves, a measure of their subjection and the disparaging attitudes of the time. As remarked by Cuthbertson and Jeeves (1999 p. 11): “Public commemoration [of black contributions and experience in the War] would have seemed to whites, if any of them had thought about such a thing, as bizarre and irrelevant”.

Remount Camps

Indian auxiliaries were employed as hospital staff, horse trainers, and transport drivers, cooks, water carriers, laundrymen and in other non-combatant roles. Though reluctant to bring in Native troops as combatants, the War office made repeated requests for veterinary, health and equestrian establishments, leading to several native contingents being dispatched to South Africa.

The breaking in and training of horses was among the main functions of the Indian auxiliaries, second only to stretcher-bearing. Faced by highly mobile Boer commandos on ponies, the later British campaigns under Lord Roberts were forced to rely increasingly on cavalry and especially on mounted infantry.

As recounted by Ramamurthi:

Syces (grooms for horses), nalbands5 (farriers) and other Indian support staff at the Remount Depots helped keep the cavalry going, much as repair and servicing facilities might do for mechanised divisions today.

Figure 3: Bengal Lancers at the Kroonstad Remount Camp.

As shown here, certain of the Indian forces carried arms,

as they were part of the Indian Army.

Photograph: Wilson, W.H. After Pretoria: the Guerilla War p. 282.

The Observatory Monument

By Ramamurthi’s calculation, a total of over 9 000 Natives of the Indian Army were eventually sent to South Africa during the three year war, either accompanying British regiments or sent in separate Native corps. But the War Office preferred to ignore their presence officially, throughout the War and in the official histories.

Nevertheless, support for a monument near Johannesburg to honour the Indian followers come from sympathetic British officers on the ground. Set in what would in 1903 would become the suburb of Observatory, the monument was unveiled soon after peace was declared, with invitations going out to councillors and other dignitaries. As recorded in Johannesburg Town Council minutes, guests were called to a ceremony below the ridge:

Funded by public subscription, with contributions from the local Indian community, the monument was unveiled in the first flush of victory, during the surge of patriotic feeling which followed the end of the war. For South Africa’s Indian community, accustomed to years of discrimination and contempt from the country’s white rulers, the monument was a rare acknowledgement of Indian dignity. As reported in The Star (1 November 1902), Indians from around the country greeted the monument with delight:

Adding further to the monument’s significance, the site was associated with Indians who formed part of the British force which occupied Johannesburg in 1900. Staffed mainly by an Indian detachment, a large Remount Depot was set up in Bezuidenhout Valley, beneath the ridge on which the monument would later be erected.

Figure 4: The Remount Depot in what became Observatory Park,

where

thousands of horses could be sheltered under corrugated iron roofs.

As many as 4 000 horses could be accommodated by this central remount station in what become Observatory Park6. Even in 1900 the location offered park-like surroundings, with large trees affording shelter for sick horses and for farriers at work. Natural springs also made it ideal for the purpose, providing a supply of water for both horses and men throughout the year (Craig 1989).

Four unknown Muslims from the remount Station were buried nearby in August 1902. The cause of their deaths is uncertain, though it is known that typhus claimed the lives of a number of Indian details in the area. The four men were originally buried in a small cemetery on the east side of the present Observatory Park, near the bowling greens. In 1964 the remains of the four men were exhumed when the municipality developed the park, with the Indian Cemetery making way for a Protea Garden. The remains were then taken to Braamfontein Cemetery for reburial, but with the Muslim section already full up, the Indians were placed in the “General Section” normally reserved for Whites.

The Observatory Monument commemorates not only these four but also many of their countrymen who died on the battlefields of the Anglo-Boer War, their graves unmarked and unrecorded7. Those who fell include Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and Zoroastrians as well as Muslims. Specific mention is made on the monument of the mens’ religious diversity. Small tablets on three sides of the obelisk are inscribed:

Many of the Indian auxiliaries - though not all -returned to India following the end of the war, never to form part of South African society. In this sense, reviving their memory may not fit neatly within a narrow conception of South African nation-building. It remains nonetheless important to acknowledge the varied, multi-racial and transnational elements which have shaped South African history. Actors in this complex and composite history include not only the South African mainstream, local minorities and immigrant populations, but includes also non-South Africans who have come, left their mark as an enduring presence on the historical landscape, and have gone from the country’s shores.

After the close of the war of the South African Anglo-Boer war, a few at least of the Indian Army soldiers remained in South Africa, becoming absorbed into the Indian community and, more broadly, into the continuing stream of South African history. Drawn from these veterans of the British Indian Army, Captain Nawab Khan and Sumander Khan were among those who participated in the seminal protest movement led by M.K. Gandhi in South Africa from 1906 to 1914.

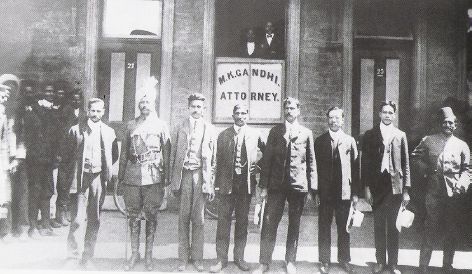

Figure 5: Gandhi, third from left, with passive resistance leaders in Johannesburg,

1908.

Captain Nawab Khan, with turban, is on Gandhi’s right.

Photograph: Transvaal Leader Weekly, 11 January 1908

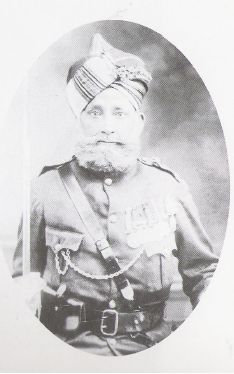

Figure 6: Captain Nawab Khan in later life. He died in 1939, aged eighty,

and is

buried in Braamfontein Cemetery.

By January 1908 Captain Khan stood trail in Johannesburg along with a fellow ex-soldier, Sumander Khan, a veteran of the Anglo-Boer War with 30 year’s service in the Indian Army. Accused of refusing to register under the Transvaal Asiatic Registration Act, the two were defended in court by M.K. Gandhi in his role as an attorney (Gandhi 1958).

On 3 January, Gandhi began his examination of Nawab Khan by establishing the military credentials of the accused:

Gandhi: You are a Jamadar8?

Accused: Yes.

Gandhi: You came to the Transvaal at the time of the War?

Accused: Yes, during the War.

Gandhi: Attached to the transport corps?

Accused: Yes.

Gandhi: What expeditions have you served in?

Accused: Burmah, Chitral, Black Hill, Tirah Expedition (1897) and the Transvaal War

Gandhi: And you were wounded three times?

Accused: Twice I was shot and once I was cut over the eye.

Gandhi: Your father was attached to Lord Robert’s staff when he went to Kandahar?

Accused: Yes, he was Subadar Major

A prominent resistance figure, Captain Nawab Khan brought a long military tradition to Gandhi’s non-violent Satyagraha (‘Truth Force’) movement of the early 1900s. The son of a major killed in the Second Afghan War, Nawab Khan joined the Indian Army at the age of thirteen years old. His campaigns included the first Sudan War of 1882-1883, Burma (1885- 1893), the Chitral Frontier (1893-1896), the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), and the Zulu Bambatha Rebellion of 1906. As a result of his leading role in the Satyagraha movement, Nawab Khan lost his grant of land and his military pension was terminated.

An earlier version of this article was published in New Delhi: Africa Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 2, 2003.

References Cited

NOTES

1 The highest ridge in Johannesburg, Observatory Ridge rises 1 808 metres above sea level. Access to Observatory Ridge, approached from Steyn Street or Gascoyne Street, is complicated by a series of road closures around the Urania Village, a suburban enclosure heavily fortified against urban decay and feared criminality spreading out from the periphery of the inner city. In the 1980s, Observatory Ridge was incorporated as part of the Mervyn King Ridge Trail, a now-defunct hiking and picnic trail stretching from Hillbrow to Bedfordview. African church groups who worhip along the hillside are the main users of the pathways, as they have been for many years.

2 The Republic of India, formed of a union of states and territories, came into existence in 1947.

3 Among those who played a crucial role in the defence and relief of Ladysmith was a unit of the Indian Army – An Indian Ordinance Field Unit – which included Indian Lascars (camp followers) – some of whom lost their lives. This Ordinance Field Park consisted of 81 tindals and lascars, 30 artificers and 5 clerks, all of them Indians, as well as 3 ordinance officers, 6 warrant officers and 9 sergeants (all Europeans).

4 See for example: J.B. Brain, Indians and the South African War, 1899-1902. Africana Journal no. 15, 1999. In attempting to give an overview of Indian participation in the war, Brain touches briefly on the contribution of Native soldiers of the Indian Army. Much of the article is however devoted to Gandhi’s Ambulance Corps and to the Anglo-English volunteers of Lumsden’s Horse.

5 Some of the terms like “nalbands” (farriers) used to describe Indian auxiliaries were transliterations of words from Indian vernacular languages. These terms cannot always be translated exactly. However, to convey an idea of the work done by these men, some of the terms roughly cover the following:

6 Observatory Park was included in the Johannesburg Town Council’s list of Parks from as early as 1910.

7 In the absence of any comprehensive records or statistics of casualties suffered by Indian troops, one has to rely on scattered reports of actions in which Native followers were involved. Here and there an Indian is reported as having been killed or wounded in action, or more commonly of having died of disease, such as pneumonia or enteric fever, directly traceable to active service. In the case of the Indian Ordinance Field Park there were no deaths and only one lascar was wounded. The overall picture of Indian casualties remains hazy and incomplete and the true number of deaths may never be known.

8 Jamadar (sometimes spelt Jemadar) denotes a rank used in the British Indian Army, where it was the lowest rank for a Viceroy’s Commissioned Officer (JCO). Typically, a Jamadar commanded platoons containing 30 – 50 soldiers, or assisted their British commander.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org