The South African

The South African

31st May 2022 marks the 120th anniversary of the Treaty of Vereeniging and the end of the 1899-1902 Anglo-Boer War. The last major armed engagement of the three-year conflict took place between the Boers and the Zulus at Holkrantz (aka Holkrans and Mthashana), near Vryheid, in today’s northern KwaZulu-Natal Province 1 in the early hours of 6th May 1902. The circumstances surrounding the action, remain however, controversial to this day; it is regarded by some as retribution for alleged Boer misdeeds 2 but is considered by others as plain, even cold-blooded murder.3 General Louis Botha described it as “The foulest deed of the war”.4 Such diverse views suggest it may be worth briefly re-visiting the event with a view to differentiating the facts, as we are able to ascertain them, from possible fiction.

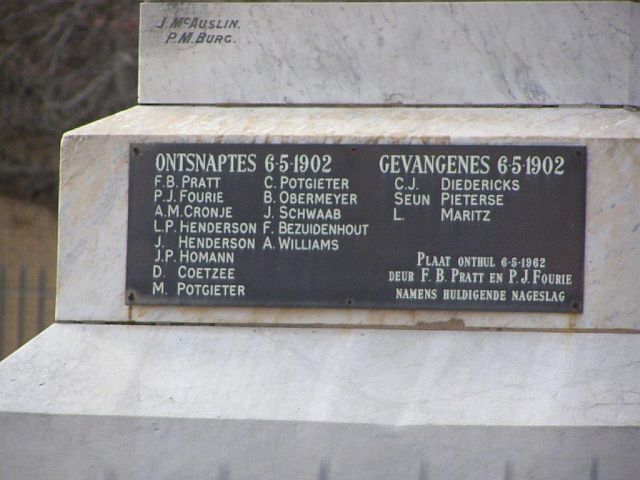

The engagement is variously described as a battle, an ambush, a sneak attack, and an incident, but is arguably more accurately and objectively understood as a significant skirmish. In essence it was a pre-dawn surprise attack on 73 Boers of the Vryheid Commando under Veldkornet Jan Potgieter 5 by 300 warriors of the abaQulusi clan of the amaZulu under command of Sikhobobo. During the attack 56 Boers were killed, three taken prisoner and 13 escaped. AbaQulusi losses were 52 killed and 48 wounded. By South African standards, these were a significant number of casualties for a relatively short engagement.

In the majority of the general histories of the Anglo-Boer War, the fight at Holkrantz receives little or no mention.6 Many, but not all, of those who do mention it, state or suggest that it influenced Boer thinking during the peace negotiations underway in Vereeniging at the time.7 While the engagement appears to have influenced some delegates quite strongly, its overall impact on the peace conference is not clear. It did, however, have a major impact on the Boer farming communities in the Vryheid-Utrecht district of the Transvaal, where it is still regarded by some members of the community as murder.8 Not everyone is, however, necessarily aware of the role which the British administration of the area played in the event.

Another feature in writings about the event is the extent to which the Boers are seen to be provocative. Some writers suggest that Potgieter not only grossly insulted Sikhobobo (there are several different variations of these purported insults 9), but challenged the abaQulusi to come and get their cattle back.10 The latter, it is claimed, responded with alacrity and in some accounts the Boers have been deemed to have got their just desserts.11

A characteristic feature of most the accounts of Holkrantz is how little reference has been made to primary documentation and consequently how little evidence is provided for statements made and views expressed. The single major exception which offers the most thorough and best documented examination of the event, is the research of S J Maphalala.12 He is the only writer who makes extensive use of primary documents – 39 in all – and substantiates his views with source-based evidence. After careful analysis of the data and available historical records, including background factors, he is almost alone in concluding that blame for the incident lay largely with the British. Minnaar and Wessels are also exceptional in that they are the only writers who indicate having consulted Maphalala’s work.13

The crux of Maphalala’s argument is that not only were the abaQulusi under chief Sikhobobo part of the combined British force based in the Vryheid area, but that they had been tacitly encouraged by the British to attack and arrest the Boers and take their cattle, even though an armistice was in force.14 They were also armed by the British – part of the chain of events which led to the incident.15 After partially accomplishing these tasks, Sikhobobo and his men could not return to their kraals for fear of Boer reprisals and were protected in Vryheid by the British army, during which period they continued to raid farms and attack and kill isolated groups of Boers.16 Chief Sikhobobo and his men became known as ‘Mr Shepstone’s Commando’ due to them being aided and abetted by A.J. Shepstone, the British appointed Magistrate in Vryheid. 17,18

As a consequence of these activities, General Louis Botha instructed that Sikhobobo’s kraals were to be burnt with a view to placing the burden of responsibility and care for the wives and children of the abaQulusi on the British. Some of the women were also suspected of providing the British with information on Boer movements. Maphalala emphasises that the Boers allowed the women to take provisions for three or four days with them to reach the British lines 15km away, before burning the kraals. Homes in which there were sick or infirm individuals were not burnt and, on occasion, the Boers accompanied the women to Vryheid to ensure their safety.19 All Sikhobobo’s cattle were confiscated.20

Maphalala argues that on 5th May, Shepstone, having ascertained from spies the position of the Boers at Holkrantz, ordered Sikhobobo to attack them.21 Such a straight-forward statement is absent from British accounts such as those of Pakenham and Warwick. The attack took place at 04h00 on 6th May, employing the traditional three-pronged amaZulu battle formation. All accounts agree that the Boer commandos did not expect an attack from the British as an armistice was in force. They had, in addition, failed to put enough sentries out, and so were caught almost completely unawares. Although some managed to fight their way out, most were surrounded and killed.

After the engagement, a British Commission of Enquiry was convened which, according to Maphalala, after ignoring some of the crucial evidence – not surprising given the sentiments of the time – concluded that the Boers had been killed because they had been ill-treating the amaZulu and thus brought reprisals upon themselves.22 Amongst the crucial evidence not taken into account was that provided by some of the Boers 23 and that Magistrate Shepstone was not only complicit in allowing Sikobobo to proceed to Holkrantz, when in terms of the prevailing armistice, British troops should have prevented the attack, and that the three prisoners were taken on instructions of Shepstone. Another item ignored was the Boer contention that relations between the Zulus and the Boers were good prior to British interference and arming of the Zulus. 24 Boers testified to the Commission that despite being alone on their farms while their men were away on commando, no Boer women or children had been attacked, harmed or ill-treated by the Zulus.25,26 Maphalala also makes no mention of any Boer insults as suggested by some writers.27

In conclusion, he suggests that the attack was indirectly or directly carried out on the instructions of Magistrate Shepstone and that the abaQulusi were merely carrying out British orders at Holkrantz.28

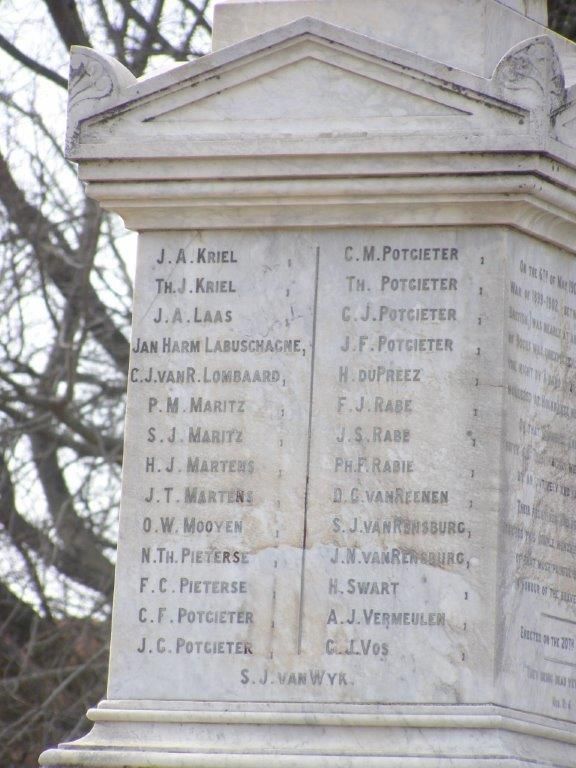

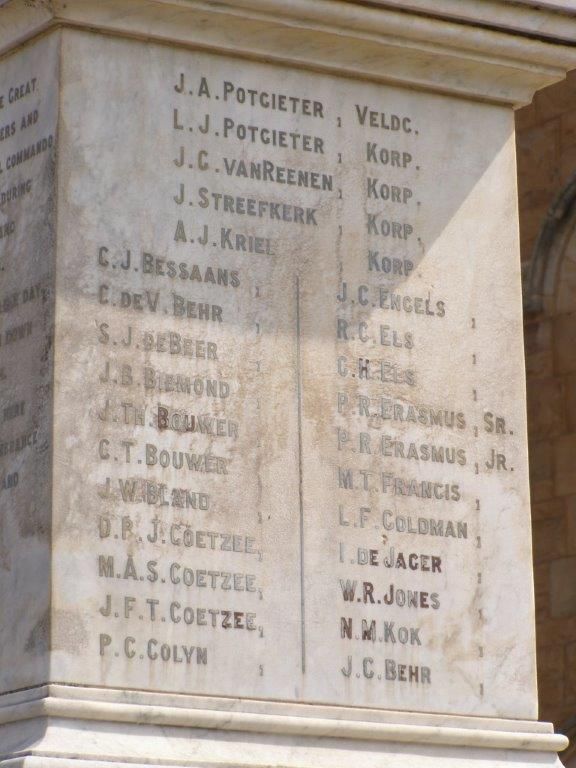

A monument to the Boers stands on the hill above the place where they were attacked and where the last of them retreated to. There is also a memorial plinth in the precincts of the NG Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) in the nearby town of Vryheid, where many of the commando members would have regularly worshipped. All their names have been recorded. No monuments have been erected to the abaQulusi who died in the incident.

Memorial on the Battlefield

Memorial in the precinct of the N G Kerk, Vryheid.

Panel bearing names of casualties

N G Kerk, Vryheid.

Panel bearing names of casualties

N G Kerk, Vryheid.

Panel bearing names of escapees and PoWs,

donors and stonemasons of the Monument

N G Kerk, Vryheid.

Acknowledgements First and foremost I thank my wife, Anne, who not only kept me good company throughout the process of gathering information but kept notes and looked after our logistics. She has also given me valuable critical comment during the writing of the article. I also wish to express particular thanks to ‘Anna-Marie’ of the farm Holkrans who acted as our guide to the battlefield, and for her warm hospitality. The staff of the Vryheid Museum is also acknowledged for their helpfulness and for sharing their knowledge and perspectives on the event with us.

NOTES

References consulted reflecting different viewpoints

Amery L S & Childers, E 1907 The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902 Vol 5 p605 London Sampson, Low, Marston & Co.

Barker Brian Johnson 1999 A concise dictionary of the Boer War Cape Town Francolin Publishers.

Brookes E H & Webb C de B 1965 A history of Natal Pietermaritzburg University of Natal Press.

Cloete Pieter G 2000 The Anglo-Boer War. A chronology Pretoria J P van der Walt & Son.

Conan Doyle Arthur 1902 The Great Boer War Reprint under Project Gutenberg Ebook, updated 6th March 2018. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3069/3069-h/3069-h.htm

De Wet Christiaan (General) 1902 Three Years War London Archibald Constable & Co Reprinted by Galago in 2005 under the same title.

Gillings Ken 2000 Newsletter of the Durban Branch of the SA Military History Society December 2000. http://samilitaryhistory.org/0/d00decne.html

Grobler Jackie 2018 Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902: Historical guide to memorials and sites in South Africa Pinetown 30º South Publishers.

Hendey Brett The Battle of Holkrans. http://www.angloboerwar.com/forum/8-events/177-the-battle-of-holkrans

Kestell J D & Van Velden D E 1982 Die vredesonderhandelinge tussen die regerings van die twee Suid-Afrikaanse Republieke en die verteenwoordigers van die Britse regering: wat uitgeloop het op die Vrede wat op 31 Mei 1902 op Vereeniging gesluit is Kaapstad Human & Rousseau [Originally published in 1909 as De vredesonderhandelingen tusschen de regeeringen der twee Zuid-Afrikaansche Republieken en die verteenwoordiges der Britsche regeering. Amsterdam

Kruger Rayne 1967 Goodbye Dolly Gray London New English Library.

Maphalala S J 1977 ‘The Murder at Holkrantz (Mthashana) 6th May 1902’ Historia 22 (1)41-46.

Maphalala S J 1979 The participation of Zulus in the Anglo-Boer War MA University of Zululand.

Minnaar A de V 1989 ‘Zululand and the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902)’ Military History Journal Vol 8 (1) 14-20 June 1989.

Nasson Bill 2010 The War for South Africa: The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 Cape Town Tafelberg.

Pakenham Thomas 1979 The Boer War Jonathan Ball Johannesburg.

Pretorius Fransjohan 1991 Kommandolewe tydens die Anglo-Boereoorlog, 1899-1902 Johannesberg Human & Rousseau.

Pretorius Fransjohan 1999 Life on Commando during the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 Johannesberg Human & Rousseau. This first appeared as Kommandolewe tydens die Anglo-Boereoorlog, 1899-1902 in 1991, also published by Human & Rousseau.

Pretorius Fransjohan 2013 The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902Cape Town Don Nelson.

Thompson P S 1994 ‘Isandlwana to Mome: Zulu experience in overt resistance to colonial rule’ Soldiers of the Queen 77: 11-15.

Von der Heyde Nicki 2013 Field guide to the battlefields of South Africa Cape Town Random House Struik.

Warwick Peter 1980 ‘Black People in the War’in Warwick P & Spies S B (Eds) The South African War; the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902.

Warwick P 1983 Black People and the South African War Cambridge University Press.

Wessels Elria 2002 ‘Die moord by Holkrans 6 Mei 1902’ Veldslae: Anglo-Boereoorlog 1899-1902 Pretoria Lapa Uitgewers.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org