The South African

The South African

George Chadwick

Probably the most important and best known battle ever to be fought on South African soil, Blood River presents a number of fascinating and apparently insoluble problems. We have few original sources on which to base a reconstruction of the events, but so much has been written and said about it that varying versions have gained wide credence.

In attempting to give an account of the sequence of events the author has taken into consideration such original sources as are available (some of which are listed in the appendix), the account given by Capt.J.R. Garden in his diary (see appendix) and the accounts given by various historians, but has relied also on his own conceptions of military probability based on the nature of the terrain as well as on the military traditions, resources and experiences of the adversaries. He is well aware that his views differ radically from those of many recognised authorities with whom he has had frequent friendly differences of opinion. He realises that other interpretations may be placed on the facts available.

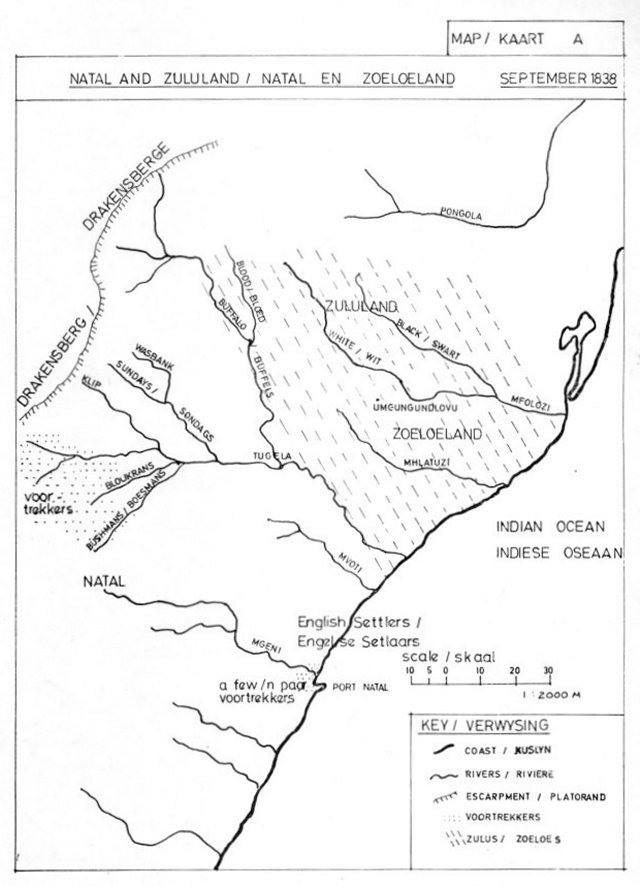

THE BACKGROUND TO THE STRUGGLE (SEE MAP A)

As is well known the first Bantu tribes to settle permanently in Natal were not highly organised nor very powerful, with the result that intertribal warfare, although common, seldom resulted in heavy casualties or the depopulation of large areas. The main accoutrements of war were light throwing assegais, a heavy stick or knobkerie and a fairly small oxhide shield. Opposing forces would advance to within assegai throwing distance, say 50 metres of each other, make much ado of stamping, whistling and threats and exchange volleys of assegais. If the groups were not tightly packed these were comparatively easy to dodge or ward off. Casualties were low and seldom fatal. The side gaining the advantage of this exchange would charge forward but savage hand to hand fighting was not common as the losers would soon break and flee.

Shaka, in building up the Zulu military empire from about 1818, changed all this. He established a well organised Zulu state with a very efficient military machine at its disposal. In the course of his conquests he scattered the Bantu tribes which he did not subdue, far and wide, leaving a large area of the Natal Midlands almost depopulated. The murder of Shaka and the accession of Dingane in 1828 made no material difference to the Zulu power because Dingane, although no military genius in the stamp of Shaka, followed his military policy and had the support of many able commanders who trained under Shaka.

Map A - Natal and Zululand

The first Voortrekker contact with Natal was in 1834 when the Kommissietrek under the leadership of Pieter Lafras Uys travelled north through the present Pondoland and visited the Natal Midlands as well as the southern banks of the lower Tugela. The lack of Bantu inhabitants in central Natal as reported by this group was the main reason why many of the Voortrekkers chose it as their goal. Piet Retief and a small party of his followers entered Natal on 14 October 1837, proceeded to Port Natal where he was welcomed by the British and further to Umgundhlovu, Dingane's chief kraal. Here he obtained a promise of land in central Natal subject to the recovery of certain Zulu cattle which had allegedly been stolen by the chief Sikonyela. On receipt of this news various Voortrekker parties streamed into Natal, establishing themselves in the Tugela, Bloukrans and Bushman's River valleys. On 20 January 1838, Piet Retief and 70 of his followers set [- 2 -] out to return the stolen cattle to Dingane. On 6 February he and his party lay murdered at Kwa-Matiwane (Moordkoppie) near Umgungundhlovu. The struggle between the Zulus and the Voortrekkers had commenced.

THE MILITARY ORGANISATION AND EXPERIENCE OF THE ZULUS

Shaka's military genius lay in the fact that he exploited the previous disorganised character of Bantu warfare by welding his forces into an organised unit armed with effective weapons. (Whether or not he was instructed by others is beside the point - his was the genius that carried the policy out.) The basic changes brought about ensured that all Zulu youths on attaining manhood were absorbed into a regiment or Mabuto where they received systematic training. The stabbing assegai with a long broad blade (approximately 35 cm long by 5 cm wide at the broadest part) and a short handle of some 50 cm was introduced as the main weapon of attack. It was held so as to deliver an underarm upward stroke to pierce the abdomen, stomach or left armpit, and from the sucking noise made when withdrawing it from the human body became known as "iklwa".

A Zulu warrior would also carry one or two throwing assegais with narrow short heads (10 or 15 cm by about 3 cm wide) and a long (approx. 150 cm) light handle. These were thrown overarm. He would also have a heavy fighting stick (iwesa - to lay low) or knobkerie and his shield which in Dingane's time was made of an oval heavy hide some 120 cm long and 50 cm wide. Regiments were trained to move at a jog trot, obey commands, launch their throwing assegais and to charge forward en masse. The basic manoeuvre was to launch the throwing assegais at a distance of 40 to 50 metres (maximum accurate throwing distance approximately 60 metres) and charge forward to engage the enemy hand to hand and if possible to hook the shield under the left edge of that of the opponent and force it to his right, leaving the lower left part of the body exposed to an upward stab. One must remember that Zulu iron was of very inferior quality and that an overarm stab into the rib cage or against the shoulder blades, while probably being fatal to the opponent, would have bent the assegai head. Even as late as the Zulu War 1879 there is good evidence that a stab through a British soldier's uniform into his chest bent some assegai heads to such an extent that they became useless.

A Zulu warrior was dressed in a loin kilt or umuTsha with a cluster of tails or hide strips hanging down in front. He might have tassles of hair hanging from his arms and legs with rattles of seed pods attached to his limbs. The colour of the shields and tassles would denote his regiment. The Zulu attack also embodied the basic aspects of what we would call the psychology of war: drumming on the shields with the assegai handles as they advanced, stamping, shouting and whistling as they prepared to throw a volley of assegais and the bloodcurdling cry of "Usutu" as they charged forward.

Although the Zulu line of command was well organised and a large army could be mobilised in a short time the provisioning of an army on the move proved to be a problem. The army was accompanied by uDibi boys carrying cooking pots with grain but unless replenishments or cattle could be found along the route the army could not stay in the field for more than about five days.

When offering battle the Zulu army was organised into four tactical units. The strongest section, composed of the older and more experienced warriors, formed the "chest" or main force while on each flank were two "horns" composed of younger and often more impetuous warriors. Their function was to race forward and surround the enemy while the chest closed to deliver the main blow. The fourth tactical unit was the reserve also composed of experienced warriors, which formed up behind the chest to be used as and when required.

[- 3 -]

This type of attack proved deadly against Bantu opponents who were not so well organised but because its effectiveness depended upon coming to grips with the enemy, it was not always so successful against Europeans armed with firearms and mounted on horses. The Zulu attack on the unprepared Voortrekker encampments in the Bloukrans and Bushman's valleys on 16 and 17 February 1838 was initially very successful but parties of mounted Voortrekkers or those who had reached fortified positions were able to beat off the Zulu attacks. On 11 April when the combined commandos under Potgieter and Uys engaged the Zulus at the so-called Battle of Italeni, Voortrekker mobility enabled them to escape the "horns" with comparatively minor losses. When the Zulus attacked the laager at Veglaer near Estcourt on 13, 14 and 15 August 1838 their tactics and weapons proved unequal to the task of breaking into a well fortified position in the face of musket and cannon fire. However they were successful in driving the Voortrekker cattle away, rendering the wagons immobile.

THE MILITARY ORGANISATION AND EXPERIENCE. OF THE VOORTREKKERS.

Those who have experience of modern armies, are prone to assume that the organisation of Voortrekker commandos was haphazard. While it is true that it was of an informal nature the commando system which had grown up in the Eastern Cape was a very effective one. All able-bodied men, some mere youths by our standards, were liable for service. A commandant controlled a commando and a field cornet a group equivalent to a small company. Each man knew his responsibilities and had to provide his own horse and arms.

There was no standard firearm available but the majority of Voortrekkers were armed with a muzzleloader very similar to the "Brown Bess" issued to British troops at this time. Some would have had better quality firearms. Many would also be in possession of "elephant guns", i.e. large calibre weapons unsuitable for firing from the saddle but deadly when fired from rests. The average musket if carefully loaded with a well fitting ball probably had a range of some 250 metres. Under stress of action, i.e. hurried loading, the effective range of a ball would be considerably reduced, say to 150 metres. When firing shot (loopers) the range would be 60 to 90 metres. Handling such a heavy and clumsy weapon presented problems with the result that the rate of fire would seldom exceed four shots per minute and under difficult circumstances would be reduced to about two. Muzzleloaders were notoriously temperamental and tended to misfire. On misty or rainy days the powder in the pan became damp, making them virtually useless.

The experience of wars against the Xhosas who made skilful use of throwing assegais (range about 60 metres) had taught the Voortrekkers when making a mounted attack to adopt a tactical formation where two commandos would advance parallel to each other with the ranks formed up in fours. The commando taking up the attack would ride past the enemy while the two files nearest would fire from the saddle leaving half the weapons loaded in case of an emergency. The commando would ride away in a loop and return to present those with undischarged weapons to the enemy while the others loaded. If firing from a laager formed by placing the wagons in a rough circle or square, the Voortrekkers would also work in groups of four or perhaps eight, half firing and half loading to keep up a continuous fire. Here spare weapons and heavy elephant guns would probably be available. In such conditions the firers would stand or kneel. A muzzleloader cannot be handled from a lying position unless one has someone to load and hand on spare weapons.

The Voortrekkers had undoubtedly learnt the lessons of their previous engagements with the Zulus. The success of their mounted parties and [- 4 -] groups fighting from fortified positions on 17 February 1838 could not have escaped their notice nor could they have been insensible to the disaster brought about by unco-ordinated action at Italeni on 11 April. The success of the fortified position at Veglaer was resounding but the serious losses suffered when the Zulus drove away the cattle during the attack and the subsequent immobility of the wagons must have given them food for thought.

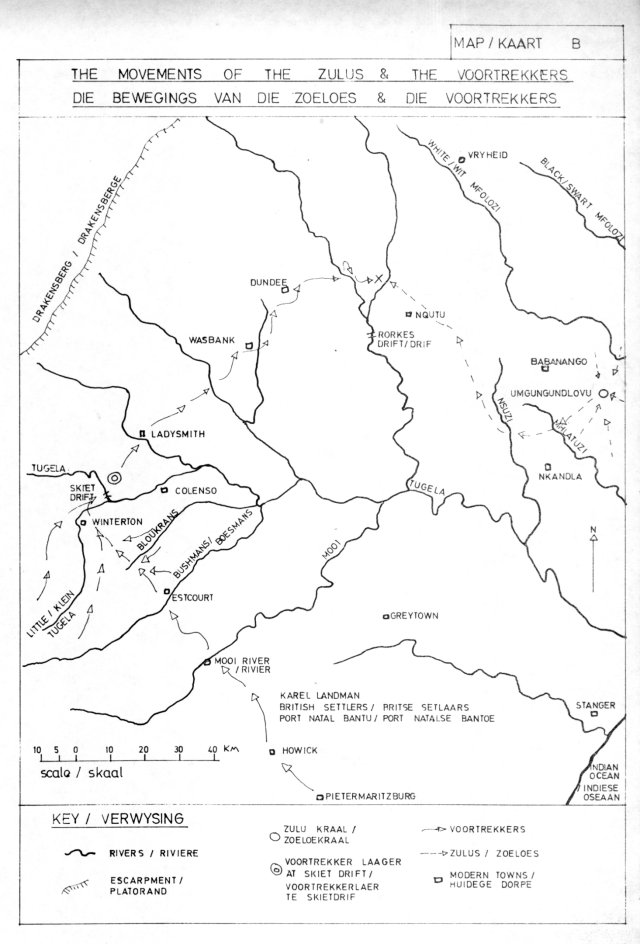

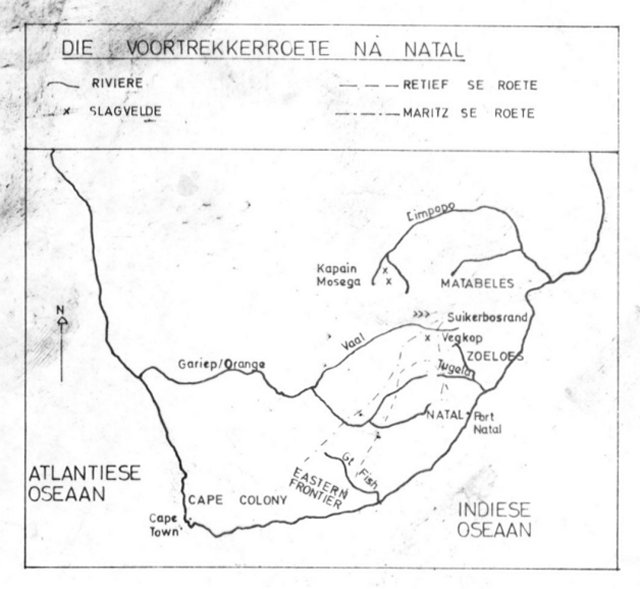

THE VOORTREKKER ADVANCE TO BLOOD RIVER (SEE MAP B)

After the defeat of the combined commando of Potgieter and Uys at Italeni and the Zulu attack on Veglaer it could only be a matter of time before the Voortrekkers took the initiative in attacking the Zulus. The death of Maritz in September 1838 left the Voortrekkers in Natal temporarily without a leader but the arrival of Andries Pretorius with 60 followers and a cannon in November 1838 changed matters. He was elected Commandant General and immediately set about organising the most powerful commando yet mobilised by the Voortrekkers. It assembled at Skiet Drift on the Tugela River on 28 November 1838, set out on 3 December and followed a route leading past the modern towns of Ladysmith, Washbank and Dundee.

Map B - The Movements of the Zulus and the Voortrekkers

Serving under Commandant A.W. Pretorius was Karel Landman as his deputy while there were six other commandants: J.H. de Lange, (Hans Dons), J. Potgieter, P.D. Jacobs, S. Erasmus, J.J. Uys and L. Meyer. With them moved a force of 464 Voortrekkers plus three English settlers, Parker, Joyce and Capt. Alex Biggar. The latter had moved up from Port Natal in the company of Karel Landman and had with them approximately 120 Port Natal Bantu and Biggar's scots cart. They joined the commando at Skiet Drift. It is probable that there were 64 wagons with the commando but as these were almost empty the span of oxen for each wagon probably numbered no more than ten, but there must have been a few spare oxen. They probably totalled some 650 in all. In all probability most of the Voortrekkers, who were all mounted, had two horses. One could guess at a total of some 750. To handle the wagons and spare horses, agterryers ("after riders" to lead the horses), drivers and leaders would be necessary. With two per wagon and approximately 100 agterryers to ride some spare horses and lead the others, as well as at least one driver and one leader per wagon, the Coloured and Bantu servants must have numbered about 230. It is certain that most of the Voortrekkers had two guns with them while it is known that Pretorius had brought a small ship's cannon. There was at least one other large cannon but some evidence points to a third, i.e. "Ou Grietjie". The range of the latter two, when firing grape-shot, pieces of iron as well as stones, was probably not more than 300 or 400 metres, but at least Potgieter's cannon must have had a range of ap proximately 3 000 metres when firing balls. It is interesting to speculate on the strength of the commando. If the figures given above are accepted, there were 475 Europeans and approximately 340 Coloureds and Bantu, giving a total of approximately 815. With 650 oxen and 750 horses there were 1 400 animals in all.

Since the beginning of their advance patrols had been sent out far ahead and by the time they reached Dundee Pretorius must have been well aware that the Zulus were advancing against him while on 14 December patrols made contact with considerable numbers of the enemy. On the 15th a reconnaissance led by Hans Dons de Lange made contact with the Zulus, probably near Nqutu. All patrols were called back by a cannon shot.

[- 5 -]

Pretorius went out with a force of some 600 men but because of the late hour, the fact that the Zulus were in broken terrain, and the fact that the morrow was Sunday, it was decided not to attack.

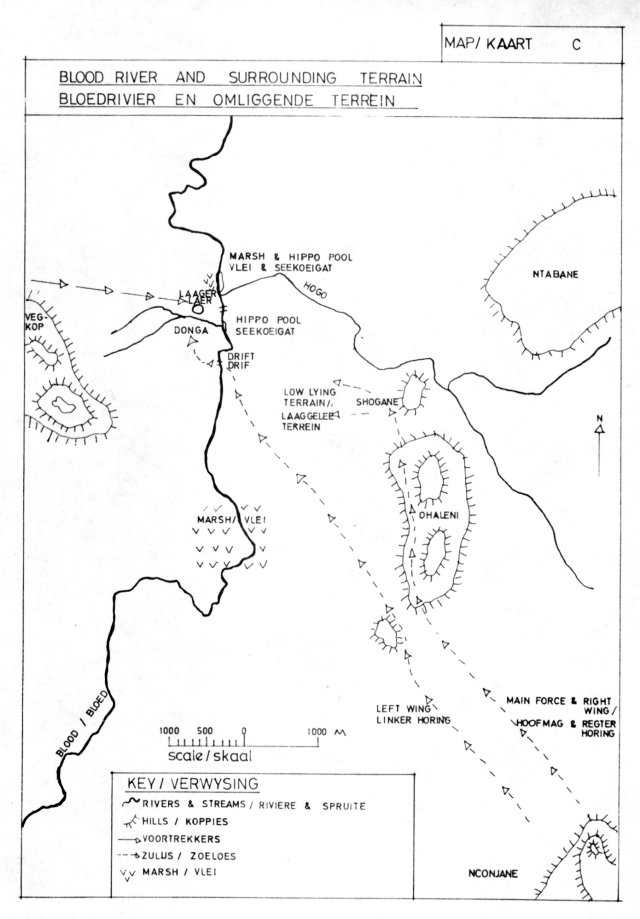

THE TERRAIN AND THE LAAGER (SEE MAP C)

The commando approached the future battlefield from the West over a low ridge to the north of the saddle-shaped hill which was later to bear the name of "Vegkop". Before them they saw a gentle, boulder-free slope levelling off near the banks of the Ncome. To the south was a deep donga joining the river. Some 400 metres away to the north, the Ncome broadened out to form a large marsh studded by several deep pools. Away to the south and about 1 000 metres downstream a wide reed-grown marsh stretched on both sides of the river. Immediately in front of them the river ran fairly high between low reed-grown banks. On the east bank stretched a level plain interspersed by reed-grown shallow pools and ending some 2 500 metres away against a low rocky ridge now known as the Shogane. About 600 metres downstream there was a frequently-used drift, while above the confluence with the donga there was a deep hippo-pool which the Voortrekkers could not sound with a long whip stick. Slightly upstream from this the river was fordable. It is important to realise that the banks of the river were heavily reed-grown, making it appear wider that it does today. The level of the water would have been higher. Research indicates that the donga had a fairly regular course but was deeper than at present while the bend in the river below the confluence may be a recent phenomenon.

Map C - Blood River and Surrounding Terrain

There must have been at least one main entrance made by placing two wagons with the disselbooms facing into the laager so that they could be pulled away to make an opening. This probably faced north, across the plain. There is much uncertainty about the number of artillery pieces in the laager but it would seem that there were at least three cannon available. The indications are that the "great cannon" was placed on the north-wast side of the laager to fire over the plain at close range. A long-range cannon belonging to Pretorius appears to have been on the east side, i.e. facing across the river to the Shogane but available for short-range work if necessary. Both these cannon would have been on light, small-wheeled carriages as was the custom at this time. They were probably fired from the ground and could be moved as required. Ou Grietjie, home-made and mounted on plough-wheels, seems to have been mounted in the main entrance. One of the most outstanding features of this laager was the "veghekke" (literally "fighting gates") which resembled a rough gate or hurdle some three metres long and 1.5 metres broad with slats placed some 20 cms apart. These veghekke were bound between the wheels of the wagons to prevent the Zulus crawling underneath or between them should they approach close enough. Here again we have evidence of forethought and careful preparation. The usual custom was to cut branches of thorn trees to strengthen a laager by pulling them under and between the wagons, but Pretorius and his commandants knew that they would be passing through an area devoid of thorn trees and had the veghekke made before the commando crossed the Tugela River. The veghekke were carried in the wagons but projected over the tail boards giving the impression of ladders as shown in some old illustrations. Another precaution had been to sew buckshot (loopers) into small leather bags (probably 11 to the bag). This made loading easier while on firing the bags would burst after travelling some 30 metres, thus grouping the shot better.

A further precaution was the hanging of lanterns on whipsticks all around the laager. It is probable that the whipsticks were near the rear and front of the wagons. The lanterns would have been of the old carriage type burning a thick candle and could not have shed a very bright or extensive light. It would seem that they were not so much intended to light up the enemy should they attack at night but to throw light on the sights of the muzzleloaders enabling the Voortrekkers to take accurate aim at an advancing mass.

Bearing in mind that the Voortrekkers would probably stand or kneel when firing one can imagine that the defenders would be grouped between the wagons, i.e. between the rear of one and the front of the other and would fire over the disselboom and veghekke. Firing from under the wagons or from the beds if the tents were in place, as seems to have been the case, would have been almost impossible. Taking approximately 60 wagons in the outer circle (omitting two for the entrance and two for ammunition) each gap could well have been defended by eight men thus allowing four to fire and four to load or half to be withdrawn to reinforce other sections or make a mounted sally.

It is interesting to speculate on the role played by the Natal settlers, i.e. Capt. Alex Biggar, Joyce and Parker as well as the Port Natal Bantu. The position of Biggar's scots cart is unknown but its unique shape when compared to a Voortrekker wagon would probably have excluded it from the [- 7 -] outer ring. It would seem reasonable to assume that Biggar, Parker and Joyce took their places in the firing line. The Port Natal Bantu are more problematical. It is known from accounts of the Battle of the Tugela fought on 11 April 1838 that Joyce, presumably a former member of the 12nd Regiment, had his division of Port Natal Bantu armed with a fair number of muskets which they were trained to fire in volleys at his command. At this battle they shot the advancing Zulus down in hundreds. It is doubtful if they were armed or organised in the same way at Blood River and probably played a passive role.

THE ADVANCE OF THE ZULUS (SEE MAP B)

Unfortunately we have no record of the mobilisation of the Zulu Army or its line of advance. However it can be safely assumed that Dingane's spies kept him aware of the movements of the commando and that by the time it had reached Wasbank he must have realised it would attempt to cross the Buffalo River somewhere upstream from Rorke's Drift. (He may even have realised, as we do, that a crossing lower down was almost impossible for a commando encumbered by wagons.) Knowing the approximate rate of advance of the Voortrekkers he would have been able to judge the general area in which his impis would meet them. It would seem reasonable that the Zulu commanders wished to engage the Voortrekkers at some considerable distance from Umgungundlovu and that the main force would have left the capital on about 12 December in order to reach the vicinity of Nqutu in three easy stages by evening on 14 December.

It is probable that the Zulus would have preferred to attack their enemy in hilly country, but knowing their own limitations with regard to staying in the field, decided to attack when the Voortrekkers' laager was formed and it was obvious that they intended to remain there for some time if necessary.

There appears to be general agreement that. the Zulu army was commanded by Ndhlela nTuli, an experienced leader who had been in command at Veglaer, and that Tambuza, another famous leader, also played a leading role. The numbers of Zulus engaged has also given rise to some difference of opinion. Some accounts make it as high as 32 000 or 40 000. While the Zulus could probably have mobilised that number of men by denuding all their military kraals it would seem very doubtful if they could handle such a large army in the field. It is more probable that the army numbered 12 000 to 15 000. This would have given the "horns" a strength of about 4 000 each while the "chest" and the reserve would have numbered about 4 000 each.

One must not assume that the Zulu attack was a series of haphazard charges: their military skill and training indicates a definite plan. More probably lack of co-ordination and impetuosity caused their plans to go awry. One may speculate that it was the intention to surround the laager, allow the "horns" to attack from East and West, and break in if possible, but to engage with a final rush of the "chest" from the South to round the matter off. It can be imagined that had such a concerted rush come from three directions at once the defenders would have faced an almost impossible task.

THE BATTLE ITSELF

In the writer's view the battle can be divided into three stages which resulted from the nature of the terrain and the lack of co-ordination of the Zulu forces.

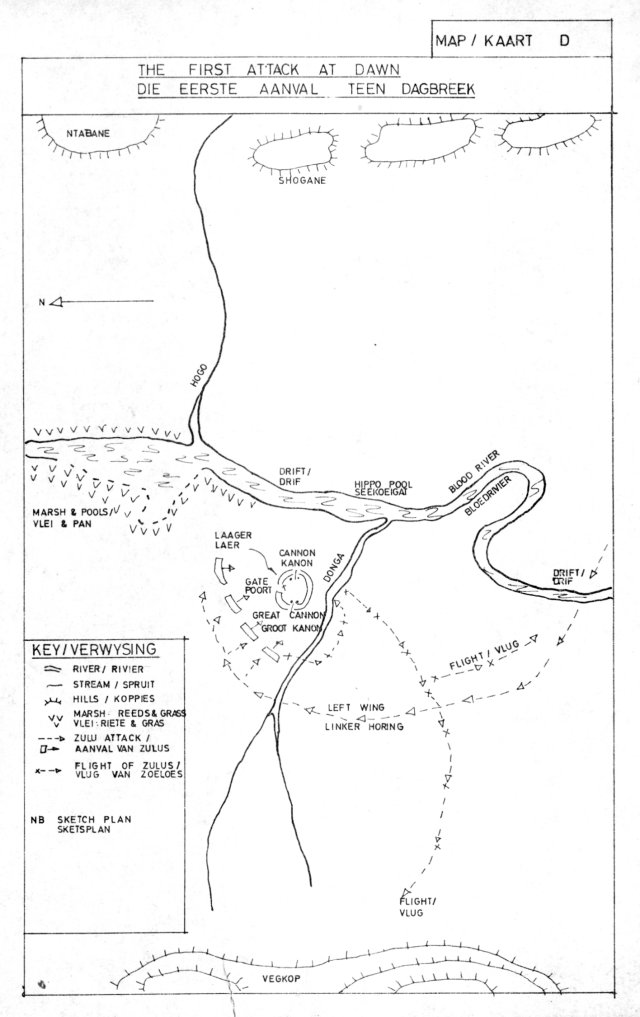

I. THE DAWN ATTACK (SEE MAP D)

Knowing that the Zulus were within striking distance the Voortrekkers [- 8 -] must have been apprehensive after evening service, at which the Vow was repeated, had been held and the lanterns were lit on Saturday 15 December. Pretorius then gave orders to close the gates and entrances ("Dat die hekken en poorten goed te verzekeren") and posted guards. Advance parties of the Zulus were near enough to hear the singing while the circle of light was clearly visible even to those on distant hills and induced many to remark that the laager was inhabited by spirits. The night was moonless and the mist which covered the river-plain must have added to the ghostly, unreal atmosphere.

Map D - The First Attack at Dawn

Assuming the above it would seem that the left "horn", composed of young warriors probably carrying black shields, advanced well before dawn on Sunday 16 December, crossed the Ncome River by the drift below the confluence of the donga and the river, circled to the west and massed on the plain to the north-west of the laager. The Voortrekkers could hear the shuffle of their feet and the Port Natal Bantu warned that the Zulus were near. This force probably numbered some 3 000. They sat quietly some 60 metres from the laager formed up by regiments in a semicircle some 100 metres deep. When the morning mists began to lift they became visible. No wonder a Voortrekker was able to recall that "the whole Zulu kingdom sat there" ('t hele Zoeloerijk zat daar - Hatting). Luckily for the Voortrekkers the day dawned dry and clear, otherwise they would have experienced difficulty with their muskets. Bantjes was able to record that the day "was made for us" (word voor ons gevormen).

Immediately the command was given to charge at which all sprang up, drummed on their shields, whistled, shouted their war-cry and dashed forward. The Voortrekkers were alert and loosed a devastating fire using the bags of loopers they had so carefully prepared. At 40 or 50 metres these would be deadly. It would seem that the cannon firing grape-shot, broken pot legs and stones did great damage, tearing swathes through the Zulu ranks. The rapid fire, lack of wind and moist air would have caused the northwest side of the laager to be enveloped in a dense cloud of black powder smoke within minutes. The Zulus charging through this would have had an even more distorted and terrifying appearance. The noise and confusion is difficult for us to imagine.

The Zulus fell in hundreds and despite fearless charges across the plain littered with their dead and dying, they could make no impression on the laager. Withdrawing from the deadly fire and circling to find a point from which to charge many began to take refuge in the donga where they bunched together and hindered one another's movements. As this became apparent, Pretorius ordered a sally from the laager to attack the Zulus in the donga. Firing down in close range the Voortrekkers inflicted heavy casualties. No wonder the Zulus broke and ran: some towards the drift over which they had come and some over Vegkop to be hotly pursued by the mounted Voortrekkers. This phase of the battle probably lasted [- 9 -] from the lifting of the morning mist at about 0630 h until about 0800 h.

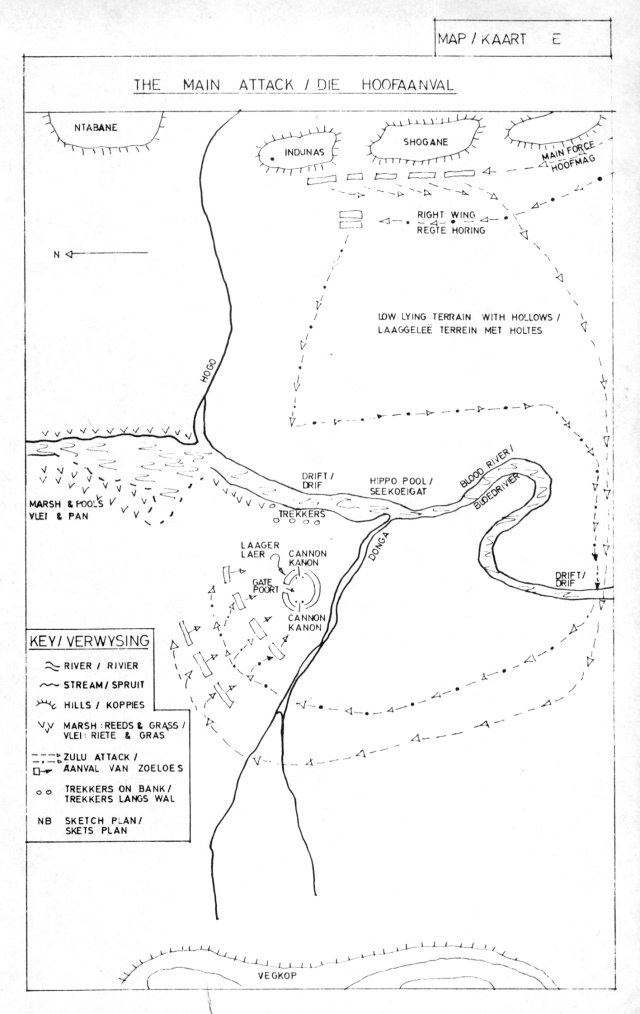

II. THE ARRIVAL OF THE MAIN FORCE OF ZULUS (SEE MAP E) Scarcely had the Voortrekkers achieved their initial success than they were confronted with a more powerful threat. The main body of the Zulu army was seen advancing from the direction of the nKonjane (the southeast) towards the low range of koppies about 1.5 km east of the river - the Shogane. If the assumption that the left "horn" launched the first attack is accepted, this force must have consisted of the right "horn" in the lead with the "chest" (main force) and the reserve following it: some 9 000 to 12 000 in all. While the majority of the Zulus, presumably the "chest" and reserve, formed up on the lower slopes of the Shogane, the commanders congregated at the extreme north of the range. At the sarne time a large force, apparently the right "horn", advanced across the plain towards the Ncome River and the laager. The hollow nature of the ground sheltered them until they were very near the river when they came under devastating fire from the Voortrekkers, who had lined the banks, and from the cannons. While this engagement was taking place, Pretorius's cannon was turned on the commanders on the conical hill and apparently killed a few with the first shot.

Unable to effect a crossing immediately opposite the laager the horn veered left towards the drift downstream from the donga. lowed by the "chest" and reserve which had been drawn up on the slopes of the Shogane.

Map E - The Main Attack

III. THE MAIN ATTACK (SEE MAP E)

Streaming across the drift the Zulus advanced on the laager but it would seem that once again a tactical error was made. Using the traditional style of attack the right "horn" and the chest should have attacked at different points but the right "horn", formed of young and impetuous warriors carrying red shields (Hatting), being in the lead appears to have stormed at the laager across the plain between the donga and the river river while the "chest", i. e. experienced warriors with white shields (Hatting), formed up behind them.

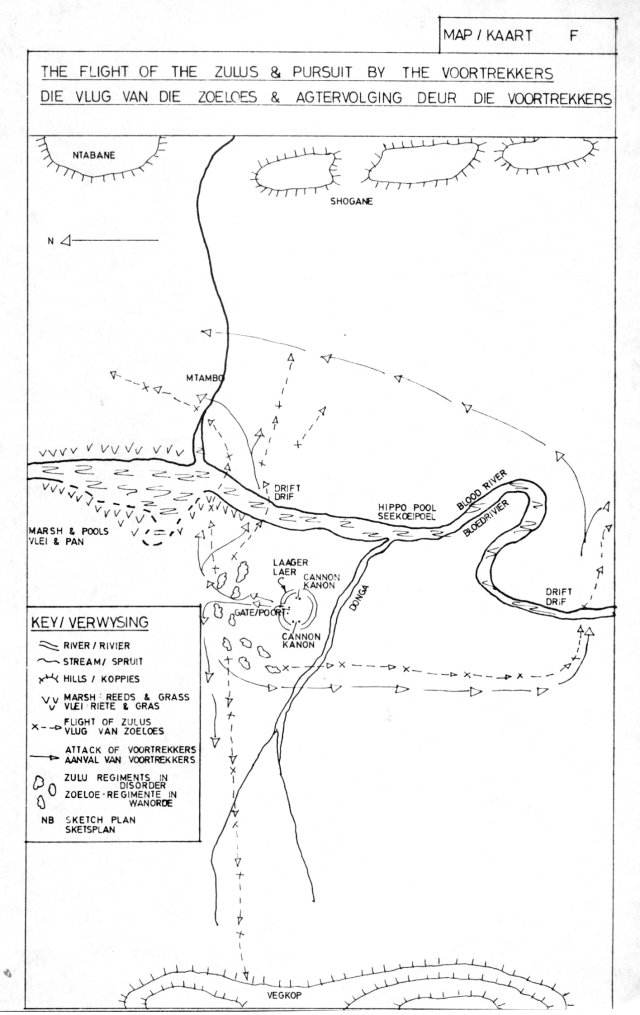

This was the most desperate stage of the battle. The right "horn", thirsting for the glory of "eating up" the white men and thus avenging the defeat of their comrades, made repeated and most determined attacks on the laager. The defenders, realising that their all depended on the outcome, redoubled their efforts to beat off the Zulus who were shot down in droves by both musket and cannon fire. The whistling, shouting, noise and confusion reached its peak. As an attack failed the older regiments of Zulus in the rear hurled insults and taunts at their comrades and often attempted to charge through them to come to grips with the Voortrekkers thus increasing the confusion and packing the rear ranks even tighter. On their side the Voortrekkers shouted to the Zulus, challenging them to come forward and fight. Bart Pretorius, the commandant's brother and a Zulu linguist rode out to taunt the Zulus in their own language. Under these circumstances the deadly thrust of the "chest" was hampered by the disorganised remains of the right "horn". At about 1100 h the Zulu attacks began to wane and many commenced to withdraw. At the same time, the cohesion of the Zulu regiments apparently broke down, making control by their commanders extremely difficult. Seizing his opportunity, Pretorius charged out with a mounted commando of some 160 men and broke the Zulu forces in two. (see map F)

Map F - The Flight of the Zulus and Pursuit by the Voortrekkers

- - - - - - - -

Cover map - Voortrekker routes from the Eastern Cape to Natal

APPENDIX : Partial list of sources.

Note - numbers in square brackets [] refer to page numbering on the original article.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page