The South African

The South African

Introduction

War, its declaration, strategy and tactics are issues of unending controversy. Less frequently addressed, however, are those involving the weapons actually used in achieving its objectives. So, by way of a change, this article will briefly examine one of these initiated by Great Britain during her imperialistic wars at the close of the nineteenth century - the so-called 'dum dum' bullet, the legacy of which continues to this day.

Display of the bullets referred to in the article

As an appropriate introduction it is probably necessary to briefly cover a few relevant basics in the field of ballistics as relating to bullets:

Muzzle velocity: This is the speed with which the bullet leaves the barrel of a rifle. It drops off rapidly over distance covered. Velocity also influences trajectory which is the path in the air followed by the bullet to its target. The higher the velocity, the flatter the trajectory and the more accurate it will be.

Weight of the bullet: This is generally expressed in grains of which there are 15.4 to the gram. Obviously, the heavier a bullet, the more power is needed to propel it at a high velocity over a long range.

Construction of the bullet: This includes shape and, very importantly, what the bullet is made of and how it is assembled. This will greatly influence the performance of the bullet once it strikes its target.

Muzzle energy: This is the force with which the bullet strikes. It is termed muzzle energy and for the present purpose will be expressed in foot pounds. It is calculated using a formula based on the bullet weight, and particularly, velocity. Very importantly, these four factors interact and deficiency in one can often be compensated by adjusting others to produce the desired effect. Obviously, the further the bullet travels, the lower is its velocity and hence its striking power and shocking effect. If a bullet is retained in what it hits, this target will fully experience both of these, while, if it passes through, much of the energy is lost. We must here also note that the composition of the target will influence the bullet's behaviour once it strikes. In the present context this target is the human body which is largely composed of water. A bullet at high velocity, however constructed, can thus induce an explosive hydrostatic effect.

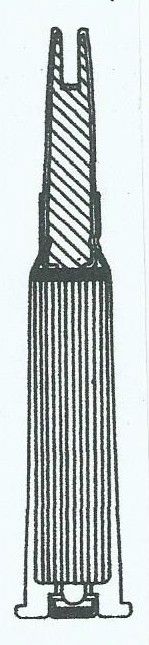

Typical early explosive bullet with internal charge

of gunpowder and fulminate.

The explosive bullet and the Declaration of St Petersburg

In the early 1850s, the British Army had just adopted a conical lead bullet of .577 calibre, shot from a rifled muzzle-loader, the Enfield. The effects of this rifle against the Russians during the Crimean War were considered satisfactory with wounds of a generally fatal or incapacitating nature. However, British hunters in Africa and India had to contend with more resistant game than Russians. They thus needed something even more effective. Their difficulties were largely resolved by the introduction of the explosive bullet, which was, in effect, a bullet of military shape, but containing a charge of fulminate and gunpowder which detonated upon hitting its target.

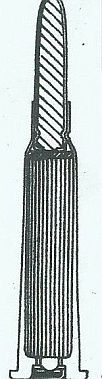

Enfield bullet

Bullets of this pattern were copied by the Russians, supposedly for use against ammunition wagons. As time has proved, the main reason a nation attempts to outlaw anything is fear that it will be used against itself. Tsar Alexander II thus called for an international conference to limit weapons amongst nations. This was held at St Petersburg and the resulting code of conduct is known as the Declaration of St Petersburg. High on the agenda was the banning of explosive bullets and, on 11 December 1868, the nations present, including Britain, ratified an agreement, one of the clauses of which was as follows:

'The contracting parties engage mutually to renounce in cases of war amongst themselves, the employment by their military or naval troops of any projectile of a weight less than 400 grams which is either explosive or charged with fulminating or inflammable substances' (https://ihldatabases.icrc.org/applic/ihl.nsf/0/3cO2bafO88a50f61c12563cd002d663b?OpenDocument, website of the International Red Cross, Declaration Renouncing of Certain Explosive Projectiles, 1868).

Development of the hollow-point bullet

The 1860s also marked the commencement of the European arms race which was largely initiated by the Prussians, who had introduced their Dreyse breech-loading rifle. Pressed for time in the race to adopt a serviceable breech-loader, the British converted their muzzleloading Enfields into what became known as the Snider rifle. The .577 of an inch calibre remained, but the lead bullet was incorporated into a self-contained brass cartridge. Keen to increase velocity and accuracy, the British set about lightening and balancing this bullet. This was partly achieved by punching a cavity in the nose and spinning the lead over to seal it. Enter the hollow-point bullet!

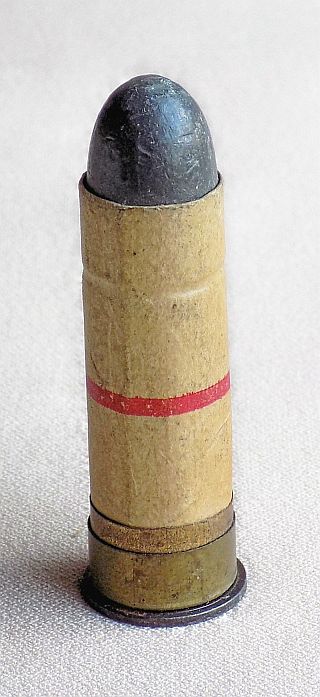

Snider Cartridge and Sectional diagram

from Majendie V D and Browne CO,

Military Breech-Loading Rifles

[Arms & Armour, 1973 reprint] p 81

This new bullet had a velocity of 1 250 feet per second (380.8 m/s) and muzzle energy of 1 666 foot pounds. Its effects upon striking flesh and bone were dramatic. Its soft lead flattened, facilitating retention in the body with a deadly transfer of kinetic energy. The chamber in its nose was thus also compressed, causing the trapped air to burst out with explosive force creating a devastating wound which immediately killed or incapacitated its victim - a decided 'improvement' over its earlier version as used in the Enfield muzzle-loader! This bullet contained no explosive substance and thus, despite its explosive effect, was entirely acceptable in terms of the St Petersburg Declaration. There was consequently no objection from any other nation (Hamilton; pp 1 250-1).

However, the Snider rifle was merely a stop-gap while a purpose-built breech-loader was developed and, in 1871, the Martini-Henry of .45 calibre was introduced. The velocity of its bullet was now 1 350 feet per second (411 m/s) with a corresponding increase in muzzle energy to 1 940 foot pounds, a considerable gain over the Snider which made up for its reduced weight and size to produce a similar wound.

Martini Henry cartridge

The Martini proved extremely successful, being greatly feared by the tribesmen against whom it was used. Once again, the fact that its bullet contained no explosive rendered it acceptable to nations which had signed the St Petersburg Declaration.

The next crucial development in the European arms race was made by France, which, in 1886, introduced an 8mm magazine rifle, the Lebel. Its relatively small projectile was propelled at the then exceptional muzzle velocity of over 2 000 feet per second (609 m/s), making for a flatter trajectory, improved accuracy and a longer range. Germany reacted with a magazine rifle in 1888 and, in 1889, came the British answer, the Lee-Metford.

The British Lee-Metford .303

Like the French and German rifles, the Lee-Metford was a bolt-action rifle with a magazine. Its calibre was reduced from the Martini's .450-inch to .303inch and this bullet was also propelled at a muzzle-velocity approaching 2 000 feet per second. Muzzle energy was 2 010 foot pounds. This was not appreciably more than the Martini, but provided the bullet was retained in the body, kinetic energy would likely produce its effect. The Lee-Metford's increased velocity also lowered trajectory and improved accuracy.

A Lee Metford Rifle issued to 1st Battalion Devonshire Regiment in 1892.

It may have been used in the Tirah Campaign where the Dum Dum was first used in British service.

How did the new .303 bullet compare to the leaden Martini bullet which it replaced? Apart from a considerable weight reduction from 484 grains to 212, the most significant difference was in its construction. Here it must be noted that, should a lead bullet be driven through a rifled barrel at high velocity, its surface will strip against the rifling intended to rotate it for accuracy. The British answer to this problem was to encase their bullet in a metallic jacket made from cupro-nickel to engage the rifling grooves. This covered the whole bullet except the base through which the soft lead core was inserted. This arrangement was entirely successful and Britain now had a rifle which equalled those of the other European powers. From the early 1890s the Lee-Metford and its Mk II cartridge with metal jacketed bullet went into full production.

The Mk II Cartridge introduced in 1893.

(Sectional drawing from Temple, B A,

Identification Manual on the .303 British Service Cartridge, p16)

The Lee-Metford's first significant test took place in India during the Chitral Expedition. This was a relatively minor campaign in 1895 to relieve a besieged fort near the present Afghanistan border. It was marked by a number of skirmishes involving British troops against fanatically brave tribesmen. These warriors, even though hit, often continued their charges right to the muzzles of the British rifles. This resistance against the rapid fire of the new rifle came as an unpleasant surprise to the British who were accustomed to the dramatic knockdown power of the Snider and Martini-Henry. Subsequently, it was found that many of the Chitrali warriors, even though severely hit by one or more bullets, had continued fighting, left the battlefield without assistance, and later made full recoveries (Broadfoot, Blackwoods, June 1898, pp 831-2), most unlike the expected behaviour of European soldiers!

The Dum Dum Mk II expanding bullet

It was obvious that the Lee-Metford's cupro-nickel jacketed bullet had nowhere near the killing power of the earlier cartridges. Instead of expanding and depositing its remaining energy in the enemy's body or blowing a large hole and pulverising bones, the .303 bullet was likely to pass right through, causing little damage unless striking a vital organ. The British soldiers began to lose confidence in their new rifle and something had to be done (Spiers, p 4). A similar problem had been noted by Indian hunters using jacketed bullets and a certain General Tweedie had invented a bullet which had largely resolved the matter.

The Tweedie Bullet, as developed

by General Tweedie for hunting

Although the Tweedie bullet had the new metal jacket, this covering had slits in the side and a shortened tip exposing the lead core. The result of this arrangement was that, upon striking flesh, the metal jacket mushroomed, or opened up like a flower, increasing the bullet's diameter and resulting in a wide wound channel and a gaping hole if it passed through. Should the bullet be retained in the body, its victim suffered the full effect of its kinetic energy.

The Indian Army did not wish to infringe patent rights and the problem was handed to Captain Neville Bertie-Clay on the staff of the Indian Dum Dum Ammunition Factory (hence the name of the specific type of bullet which he was soon to develop). Clay's solution to the problem was most effective, involving merely a slightly altered Mk II bullet which, instead of having a full cupro-nickel jacket, had one slightly shortened thus exposing one millimetre of the lead core at its tip (Spiers, p 4). 'Dum Dum' has now become a generic term often incorrectly applied to all forms of expanding bullets rather than to this specific pattern.

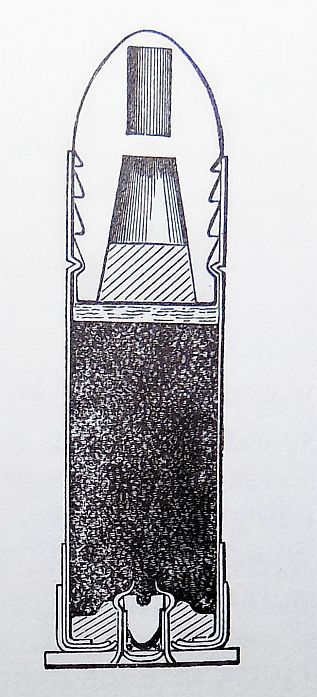

The Indian Mk II Special or Dum Dum cartridge

(Sectional diagram from Temple, Identification Manual

on .303 British Service Cartridge, p17)

This bullet, the Dum Dum Mk II, special as it was officially called, was soon to be tested during late 1897 in what became known as the Tirah Campaign, when an Afridi tribe revolted in the region of the Kyber Pass. British troops armed with their Lee-Metfords and new expanding Dum Dum bullets encountered fierce resistance. However, the results, most particularly at close quarters, were all that had been hoped for. The resulting wounds were similar to those produced by the trusty Snider and Martini-Henry: any limb struck almost always required amputation, while wounds to the body or head were generally fatal. It should be noted, however, that at distances exceeding 400 yards (366 m) the destructive powers of bullets of this sort decreased rapidly, eventually producing wounds similar to those of the fully jacketed Mk II (Ogston, BMJ, 17 September 1898, p 815).

Naturally, events in Chitral and the Tirah had been closely followed back in the United Kingdom. High Command soon became uncomfortably aware of the shortcomings of the Lee-Metford with its Mk II ammunition. A supply of Dum Dum cartridges was imported from India and tested. However, the War Office decided to adopt its own cure for the Lee-Metford's shortcomings: the Mk IV cartridge with expanding head, developed at Woolwich.

The Mk IV Bullet

The Mk IV bullet differed from the Indian Dum Dum in that it was merely a standard Mk II with a ⅜-inch deep hole punched into its nose, creating a cavity reminiscent of the old Snider bullet, another hollow point, which, when encountering a moist substance such as flesh at high velocity, was subjected to extreme pressure causing its nose to burst open. This increased its diameter with similar effects to the Indian Dum Dum, the Snider and the Martini (Spiers, pp 4-5).

Mk IV Cartridge with expanding bullet

(Sectional diagram from Temple, Identification Manual

of .303 British Service Cartridge, p 19)

Once again, the consciences of the War Office were clear. Despite the new bullet's explosive performance, Britain's St Petersburg Declaration had not been violated as the Mk IV contained no explosive. Whether, of course, the Mk IV's effects met the spirit of this commitment was another matter! It was officially adopted in February 1898.

However, before adequate supplies could be produced, the forces under Kitchener had already advanced into the Sudan with the intention of overthrowing the Khalifa and avenging General Gordon. The prospects of facing the fanatical Dervishes at close quarters with the Lee-Metford rifle and its ineffective Mk II ammunition were obviously a matter of serious concern to General Gatacre, the second in command. His contemporary report reads: 'The present-shaped bullet of the .303 Lee-Metford rifle has little stopping power. So, I am altering the shape of the bullet to that of the Dum Dum bullet. I do this by filing the point off. Before I left Cairo I provided 400 files and small gauges to test the length of the altered bullet and daily we have 2 800 men at this work. I borrowed 50 railway rails and mounted them flat side uppermost to form anvils upon which to file ... I am getting on very well with altering the ammunition. We have 3 000 000 rounds to alter, but are making good progress, altering 80 000 rounds per day' (Meredith, p26).

Mk II with filed tip as prepared

by General Gatacre in the Sudan.

(Sectional diagram by Temple, Identification Manual

on the .303 British Service Cartridge, p 16).

These home-made dum dum bullets were used at the battle of Atbara, on 8 April 1898, when the British stormed an entrenched Dervish zariba (protective hedge around a camp). At close range, they proved effective, but there was a price to pay. The tips of the bullets were no longer rounded, but square, and these cartridges were inclined to jam when fed into the breech from the magazine during rapid fire (Broadfoot, Blackwoods, September 1899, p 418). This was a matter of serious concern, but fortunately an adequate supply of the new Mk IV cartridges, with their hollow-pointed expanding bullets, arrived during May and the substitute dum dums were used up in volley-fire practice.

The Battle of Omdurman, which saw the forces of the Khalifa routed, took place on 2 September 1898. Mk IV cartridges were used by the British soldiers in their Lee-Metford rifles and Maxim machine guns. The Egyptian troops were armed with the obsolescent, but effective, Martini-Henry. Personal accounts concerning the wounds inflicted by the new Mk IV bullets at Omdurman are rather non-committal. However, back in England they were considered to have been effective. In all probability the results proved disappointing. As previously mentioned, it had been found that, at ranges exceeding 400 yards, the effects of the dum dum and Mk IV bullets differed little from those of the solid Mk II. Nowhere did the Dervishes get closer to the British lines than 800 yards (731 m).

Meanwhile, back in England, problems had arisen, both political and technical in nature. Firstly, there was a parliamentary concern that the use of Dum Dum and Mk IV ammunition by the British would cause other European nations to follow suit. The parliamentarians were obviously reminded that, since the bullets contained no explosive, they were internationally acceptable, and, moreover, the wounds caused were no worse than those of the Martini and Snider, which had raised no international concern (Hansard parliamentary reports: 25 February and 1 March 1898). Secondly, a technical problem had arisen. It was found that heat and pressure generated upon firing softened the lead core of the Mk IV bullet to the extent that it occasionally squirted out through the hollow nose, leaving its metal jacket in the barrel. If undetected this could cause the rifle to explode when fired again. This matter was also raised in Parliament and resulted in the withdrawal of the Mk IV cartridges from the South Africa Garrison.

However, the military commitment to the expanding bullet remained, with the problem being resolved by merely adding antimony to the lead in the bullet's core to harden it. Thus was introduced the Mk V cartridge which, in other respects, was identical to the Mk IV hollow point (Spiers, p 10).

The Hague Convention

Another political issue originated in Germany, where Professor von Bruns, Surgeon-General of the Württemberg Army, conducted experiments with British Mk IV ammunition and German sporting cartridges approximating the Dum Dum. He used live animals and human cadavers. His dramatic results were presented to the German Society of Surgeons which, in turn, petitioned the German Government to promote an international agreement whereby only fully jacketed bullets could be used in war (Ogston, BMJ, 25 March 1899, pp 754-5). Unfortunately for Britain, the von Bruns report was shortly followed by another international arms conference, this time held at The Hague. For nations such as France and Germany, which never lost an opportunity to embarrass and inconvenience Britain, this was a wonderful opportunity to make a major issue of the use of expanding bullets.

Major General Sir John Ardagh,

Great Britain's representative at The Hague, 1899 (Source: Wikipedia)

Britain's justification, one of 'military necessity', was presented by her delegate, Sir John Ardagh at the conference: 'In civilised war a soldier penetrated by a small projectile is wounded, withdraws to the ambulance, and does not advance any further. It is very different with a savage [sic]. Even though pierced two or three times he does not cease to march forward, does not call upon the hospital attendants, but continues on and before anyone has time to explain to him that he is flagrantly violating the decisions of the Hague Conference he chops off your head. It is for this reason the English delegate demands the liberty of employing projectiles of sufficient efficiency against savage races [sic]' (Proceedings of the Hague Peace Conference, p 343).

Significantly, the American delegate, a Captain Crozier, argued that a bullet should be judged by the wound it caused and not by its construction. This was an important point with later ramifications. The motion against the use of expanding bullets in any war whatsoever was carried by 22 votes against Britain and America. America was considering their use in the Philippines (Tuchman, p 262)! The wording of the motion, which was adopted on 29 July 1899, reads: 'The contracting parties agree to abstain from the use of bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body, such as bullets with a hard envelope which does not entirely cover the core or is pierced with incisions' (Hague Peace Conference, p 262). Nations ratifying this clause of the Hague Declaration were bound in conflicts between each other, provided the other side was not joined by a non-signatory. Britain and the United States had the option of later agreeing to abide by this clause, but without ratification. As is later recorded, Britain did so.

Soon after the Hague Convention, the Boer War commenced in South Africa. One week later, the Mk V Cartridge hollow point was officially approved for issue. Since Britain was not bound by The Hague Convention and the Transvaal had not participated in it, this cartridge could have been used. Although the British considered the Boers a race of primitive farmers, they were white, and that made the difference. Requests for the issue of the Mk V by senior officers were refused, and only the Mk II cartridge was authorised (Spiers, p 11).

Regrettably, the Boer War was not entirely without the use of expanding bullets. There is proof that some Mk IV cartridges were fired by the British during the Armoured Train incident and it appears that the Boers occasionally used soft-nosed sporting rounds in their Mausers or tampered with the points of their issued ammunition.

Post-Boer War developments

Even though the Mk V Cartridge was declared obsolete in January 1903, production recommenced later that same year following the virtual annihilation of a British detachment at Gumbura in Somaliland.

Mk V Cartridges were despatched, but the extent to which they were actually used, if at all, is unknown (see D E Watters, www.the gunzone.com/dum-dum. htm/). The final official use of the Mk V expanding bullet was during the 1906 Bambatha Rebellion when these cartridges were used against the Zulu (Stuart, p 59). Direct evidence of the results is lacking, but it is understood that some members of Natal units who took part in the close range shooting of Bambatha's warriors at the Mome Gorge were haunted for years afterwards by their experiences!

A second Hague Convention took place in October 1907. Two weeks later, Britain agreed to abide by, but not ratify, the provisions relating to expanding bullets as previously provided for in 1899. However, by that date, this would seem to have been merely a political gesture. By then, the old Mk II Cartridge had been replaced by the Mk VI. To all appearances, this bullet resembled the standard Mk II, but, in fact, its Hague-compliant unbroken metal jacket on the nose had been made thinner in the expectation that it would rupture allowing the bullet to expand upon high velocity contact with flesh and bone. Actually, the modification was not particularly effective (Watters, www.thegunzone.com/dum-dum.htm/ ), but this setback was not serious, a most effective replacement being in development by then.

Other nations, most particularly Germany, had adopted what was known as a 'spritzer', or sharp-pointed bullet. This shape, combined with a reduced weight, resulted in a higher velocity and flatter trajectory with improved accuracy. Obviously, with a lighter nose and most of the weight concentrated at the rear of the bullet, this pattern was less stable upon contact with a target and, if this target happened to be flesh, it had a tendency to cartwheel, creating a very severe wound. The British Mk VII Cartridge entered the arena in 1910.

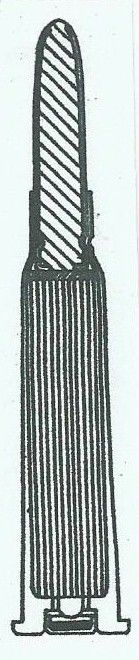

The Mk VII Cartridge with aluminium or fibre tip.

(Sectional diagram from Temple, Identification Manual

on the .303 British Service Cartridge, p 22).

As in the case of the Mk VI, the construction of the Mk VII could not be faulted in terms of the Hague requirements. It was covered by another Hague-compliant, unbroken, cupro-nickel jacket. Officially, to reduce weight even further and thus increase velocity and improve balance, the British version of this design incorporated an aluminium or fibre insert in the point, replacing the front of the lead core. This arrangement, combined with the new streamlined shape had the effect of lowering weight from the Mk VI's 212 grains to 174, thus increasing velocity from 2 000 feet per second to 2440 (609 m/s to 743 m/s). Kinetic energy increased from 2 010 foot pounds to 2 310. However, in our context, the lightened tip even further lowered stability upon contact with flesh, according to Watters (www.thegunzone.com/dum-dum.html ). This cartwheeling bullet, at high velocity, resulted in wounds recalling the good old days of the Snider and Martini-Henry.

Despite German indignation, referring to this bullet as a 'latent dum dum', the Mk VII's credentials in terms of the Hague requirements of an unbroken metallic jacket remained impeccable. It continued to serve the British for more than 50 years through two World Wars and Korea with its last users probably being British snipers with their .303 No 4 Mk I (T) Rifles during the early days of the problems in Northern Ireland.

Into the 21st century

Although the Hague Convention, with its exclusion of 'bullets with a hard envelope which does not entirely cover the core or is pierced with incisions' remains officially in force, modern technology has rendered its provisions largely irrelevant. As previously mentioned, in connection with wounding capacity, bullet construction, weight and velocity interact. In the days of the Dum Dum and hollownosed Mk IV bullet, muzzle velocities were relatively low. Currently, military bullets are generally lighter, but have very high velocities, many well exceeding 3 000 feet per second (914 m/s). The destructive hydrostatic effect of such bullets at short range is phenomenal, irrespective of construction. A case in point is the use by American snipers of cartridges containing the Sierra-designed Matchking or M 852 bullet.

The Sierra Matchking or M 852 bullet.

Note the pierced jacket and hollow nose.

(Photo: Small Arms Defence Journal, 23 August 2012).

The M 852 bullet is renowned for accuracy at all ranges, a product of its construction, which incorporates a solid base. This, in turn, is facilitated by a pierced tip with a hollow nose, enabling both insertion of the lead core from the front and improving ballistic balance. The American justification of these characteristics, reminiscent of both the British Mk IV and Mk VII, is interesting and perhaps has some validity. Firstly, it is emphasised that the United States is not bound by The Hague Convention, nor has it ever been. Secondly, Captain Crozier's argument of 1899 again comes to the fore. As stated above, he advanced the view that bullets should be judged by their wounding capacity and not their construction. It is here claimed that the hole in its tip of the M 852 bullet is very small and that the wounds it causes are no worse than those used by other nations. At the longer ranges at which snipers usually operate, this is probably correct.

Although the United States was again not a signatory, wordipg contained in the 1977 Geneva Convention is also examined in mitigation: 'It is prohibited to employ weapons and projectiles of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering'. The Americans' argument is that the wording 'unnecessary suffering' was not defined and, in their opinion, the need for accuracy at long range and the sniper's obligation to avoid collateral injury, particularly to civilians, results in a strong military necessity, which far outweighs any undefined level of unnecessary suffering (Hays Parks, 1990). Internationally, also, certain police forces are equipped with hollow-nosed expanding pistol bullets which they maintain are necessary to protect their men in close combat situations. This is achieved by exploiting the stopping power that accompanies expanding bullet retention in the body with its maximum transfer of kinetic energy. Here again, limited penetration also avoids collateral injury to civilians in urban environments (see the Wikipedia entry for the hollow-point bullet, https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollowpoint_bullet).

Thus it would appear that we are back where we started. Expanding bullets and those creating severe wounds remain in service. As in the 1890s, the justifications are military necessity and close range stopping power. The only new angle is the cosmetic need to avoid collateral injury to civilians! Perhaps, the British were merely 120 years ahead of their time?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Spiers, E M, 'The use of the Dum Dum Bullet in Colonial Warfare' in The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Volume 4,1975, pp 3-13.

Stuart, J, The History of the Zulu Rebellion 1906 (Macmillan & Co Ltd, London, 1913).

Tuchman, B W, The Proud Tower (Papermac, London, 1988).

Website of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Treaties, States Parties & Commentaries: Declaration Renouncing in Time of War of Certain Explosive Projectiles, 24 November to 11 December 1868 (https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/O/3c02baf088a50f61c12563cdOO2d663b?OpenDocument).

Watters, D E, 'The truth about Dum Dums' (www.thegunzone.com/dum-dum.html).

Wikipedia, Hollow-Point Bullet (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollow-point_bullet).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org