The South African

The South African

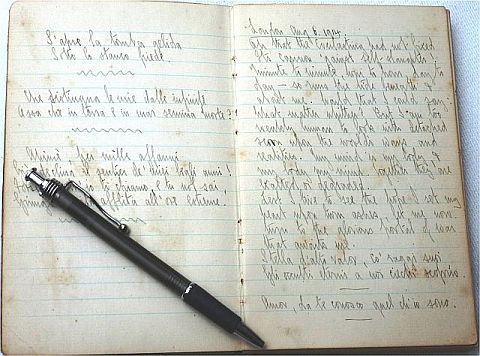

I have in my hand a small diary which is a hundred years old. It belonged to my Grandfather, who took part in the Great War (1914-1918). I met him a few times when I was a little girl, but I was too small to appreciate the magnitude of what he had experienced. His diary is interesting because personal diaries were expressly forbidden, and his descriptions of some of the events differ from official accounts. In his words, he brings to life some of the major events of the War, such as the Christmas Truce, Gallipoli and the first Day of the Somme. Like many young people of his time, he loved poetry, so his writing is quite poetic ... there are many beautiful descriptions of mud, but it would never be a best seller today.

Diary cover and sample page

The volunteer

Born in Grahamstown, Harold Sampson was a Rhodes Scholarship student, who was studying law at Oxford University when war broke out in 1914. Caught up with patriotic fervour, he volunteered as a private with the Artists' Rifles two days after war was declared. He was 23 and did not want to mis_s out on the grand adventure which he believed would be over before Christmas. There was a shortage of uniforms. He wrote: 'with a boy's impatience I buy one for myself.' .. second-hand. I wonder what its first hero died of, disease or glory?'

Harold Sampson

The Artists' Rifles was the volunteer 28th (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment. It was one of the new Territorial Force units set up to supplement the regular army. The Artists' Rifles (known later as the 'suicide club') was made up mostly of university men and public schoolboys.

The Artists' Rifles badge

On 27 October, after undergoing some basic training, his battalion set sail for France. Harold was shocked by the state of the soldiers he met there: 'A parade of stragglers from the retreat in all stages of unshaven weariness. The "Ragged regiment" indeed! I had not thought its picture could be found in the British army'. This was what was left of the original British Expeditionary Force, who had suffered shocking losses in the opening days of the war with 90 per cent of its soldiers killed and with officer losses being the highest.

The reality of war. New recruits were often shocked to see

the state of some of the soldiers returning from the frontline.

On 6 November 1914, on their way to Ypres, the Artists' Rifles were suddenly and dramatically halted. The Commander-in-Chief, Earl French, interviewed their Colonel, and in a desperate experiment, invited 50 of the men to volunteer as probationary officers in what was left of the regular army. Harold tossed a coin and volunteered. Thus, on 13 November, he joined the 2nd Battalion, The Border Regiment, of the 20th Brigade, 7th Division, as a probationer officer. There was no time for officer training. Harold noted: 'I confess my awe at finding myself in a brigade with the first Grenadiers, the 2nd Scots Guards ... and the 2nd Gordons ... without the least badge of rank or elementary knowledge of an officer's duties'.

The next day Harold went to the frontline, still in his Territorial private's uniform and Artists' Rifles badge with the addition of a 'pip'; in command of seasoned regular soldiers of the 7th Division. For much of November and December the diary is about the terrible conditions in the trenches: the bitter cold, the mud, the trenches collapsing and burying people, and the feelings of hopelessness and despair.

18 December: Rouges Banes, Aubers Ridge

Harold went into action for the first time. He wrote: 'The signal for our battalion's attack will be a whistle from the Scots Guards. A few rounds of shell on the Bache [Germans] momentarily lighten our darkness, and then a glorious cheer fades into the gloom and is drowned in a sweeping tide of fire. I find myself blankly staring into the rainy night where they have gone ... '

Their Division lost over seven hundred men that day, without gaining any ground.

Three days later, two men in Harold's platoon, Privates James Smith and Abraham Acton, spotted wounded men lying in No-Man's-Land, and went out twice to rescue them. They were awarded the Victoria Cross for their brave rescue. According to family legend, Harold was also nominated for this award, as he took part in the second rescue. The official account said it was during the day and under heavy fire. Harold's diary is different. He noted that it was at night and there was no fire.

He wrote: 'At eleven (pm) I return ... I am told that the two men have been out for almost an hour. Wondering what their delay is I wander forth in a search. Our corner of the war seems asleep, save for a distant machine-gun and a sniper nearer by with insomnia. Presently two figures loom towards me, proving to be my men carrying a body and, with it, much smell of decomposition. To my surprise their burden is by no means dead, but wounded in the groin. He tells us of another fellow still alive, lying a little nearer the Boche. So, after handling the first into the trench, we return for the other. '

'[We] locate him, after some search, in the trip wire apparently about twenty yards (18.3 metres) from the German line .... 1f they have a sentry, how he fails to notice my waterproof cape flapping in the wind is a mystery ... We lift the poor lad from the stinking mud - himself smelling like a corpse, but alive - and carry him back. Scarcely a shot is fired within a hundred yards (91.4 metres)'.

December 25: Christmas Truce

Harold wrote: 'We hear that there is a truce on in the line, for the burial of the dead of the 18th. And, what's more, Briton and Boche are now most amicably conversing together by word, sign and deed'. Some historians report that it was a one day wonder, but in the line where Harold was, it went on (unofficially) for over three weeks.

Across No-Man's Land. The Christmas Truce, 25 December 1914.

On December 26, he wrote: 'The truce, although officially expired, continues by mutual consent... mud has made the whole world kin. Their trenches are apparently as damnable as ours. They say they won't shoot if we don't. .. Not a shot can be heard. Men stroll about as they please, as at a mighty picnic - except that you may not picnic within your enemy's gate ... Like an evil dream, war and enmity have vanished ... Leave it to the men. They will shake hands and depart for their homes today'.

Three days later: 'Our little peace remains as firm as ever, so much so that a Boche' artillery officer politely sends word that his battery is about to fire on an area visible from the line where a number of our men are carelessly strolling about. He thinks it only fair to warn them to get away.' On the day after that, Harold exchanged souvenirs: ' ... I wave to a lean German, go out and meet him, and exchange a coloured handkerchief for the national pipe. He says the pipe was issued to him at Christmas, but that he does not smoke ... '

On 8 January 1915: 'I receive orders to open fire on the alleged enemy. Duly advise him that war is, re-declared and that he would do well to take cover.

Hereupon I put a section up which fires over and towards Germany. But our friends over the way take no more cover than before. They merely look pained and incredulous ... Anyway that is quite enough war for today'. Finally, on 12 January, Harold noted that the war was on again.

Shot at dawn

Conditions in the trenches got even worse as the war continued. On 20 February: Harold wrote

'most of the men will hardly stand their pitiful condition much longer. They look like slimy sacks of mud as they sleep huddled up on the parapet.' Soldiers who could "not bear the situation anymore and breached military discipline were court-martialled and shot at dawn. On 6 March, Harold witnessed the execution of Private James Briggs from his company, who had tried to desert. The whole battalion had to witness it and its own men made up the firing squad.

' ... the prisoner is marched out between his warders. The front rank of the firing party is already kneeling. Shrunken with fear he is hurried, stumbling, to the stake, fastened at the shoulders with the black loops, and blindfolded despite his protests ... "Present! Fire!" - and the wretched being sags from the pole. Instantly we are turned about, and marched off. The raw wind blows in our faces, and not a man has the will or wish to speak. Thus the machine, which all hearts hate and dare not stop'.

In 2006, the British Ministry of Defence gave in to strong public pressure, and posthumously pardoned 306 executed soldiers on moral grounds. Briggs was one of them.

On March, 11, Harold was badly wounded in action at Neuve Chapelle and he was shipped back to a London hospital to recover.

Gallipoli, September 1915

In September, Harold had recovered from his injuries sufficiently to be transferred to Gallipoli, and to the 6th Battalion, The Border Regiment, at Suvla Bay. He commented on how vulnerable the troops were: 'Beyond belief the bay is crammed with stores, hutches, mule-lines, tents, men. All within Turkish range and sight. Why don't they blow the whole show to bits? Apparently it is a more amusing diversion to drop destruction unexpectedly...'

On 11 November, he was badly wounded by a shell, and was evacuated to London. After recovering from his injuries, Harold went back to light duty, until it was time to return to the Front.

The Battle of the Somme, 1916

On 5 June 1916, Harold returned to France and joined the 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment, in the 87th Brigade of the 29th Division who were preparing for the Battle of the Somme: 'Another dip in the lucky packet', he noted.

On 23 June, he wrote: 'All we have to do is to march at a leisurely pace across No-Man's-Land ... with the ultimate object of taking the Beaucourt Redoubt across the valley... ' Harold's diary records that he survived, but with a fractured right arm, so he had to teach himself to write with his left hand before he could record what had happened: On 30 June, they had marched to the frontline: '... Gradually, it seemed, we were being drawn into the Gulf of Hell. A muzzle flashed from every hedge and mound. When a fifteen-inch Howitzer beside us blasted the sky, one's sense of gravity was suspended. Such things confirmed our confidence. Hearts were high with the promise of victory, .. At last we entered the communication trenches ... Soon they were becoming crammed to the last foot with doomed but merry men, smoking the night away ... The intensity of our bombardment appeared to increase hourly ... '

'1 July: At 07h 10 am we had our platoons on the fire-step ... The bombardment had reached its maximum intensity ... Presently the order to fix bayonets was passed down by example, words being inaudible. Then the village of Beaumont-Hamel rose on the air like a monstrous hill, almost solid, to a height of apparently 200 feet (60.9 metres), and collapsed in a disintegrating mass of debris ... One thought that the bowels of the earth had burst ... The S[outh] W[ales] Borderers now began to emerge from the frontline. No sooner were they all out and moving - after the lapse of perhaps a minute from the lifting of the barrage - than a fresh but familiar sound became audible: German machine guns. As the S W Borderers advanced down the ridge, columns of earth shot up about them, and bullets swarmed over us like bees ... '.

1 July 1916. Over the top.

'... I trembled to think of our compact marching formation. A charge with the Light Brigade would have been preferable ... Fraser then gave the signal, and climbed out. With fatalistic abandon, I did likewise. My men followed me, I believed; certainly I had no doubt they would. Through our first wires we went ... and (eventually) into No-Man's-Land. I felt that I was walking on air with a charmed life ... With growing amazement, I caught glimpses of Fraser and Stuart striding unscathed on my flanks ... On we went over that unnatural earth, littered with smoking shell-holes, and through that blurred atmosphere. The wire we passed had been tortured into tangles thick with rusty grime. The grass was like a macerated fungus. A sickly greyish hue had beset everything. '

' ... On entering No-Man's-Land, we should have borne 15 degrees to the right, but at that stage no one seemed to worry about such a formality. As we were merely advancing until killed or wounded - our objective being obviously unattainable - what matter what angle we took! Suddenly an intangible force, like a wind, caught my right arm and jerked me round off my balance. I stumbled to the ground. '

A bullet had fractured his right arm: 'When I looked up after those moments spent in examining my arm, I beheld our advance, within a few charmed and fatal yards, ebb to its end ... ' With great luck, Harold was able to take cover in a shell-hole nearby. 'Soon the machine guns, which had partially subsided, reopened with fresh fury. This meant "0" Company ... Then later, still another uproar of swishing lead. I am told the Newfounders got this ... '

Harold then had to endure the terror of being a target for the whiz-bangs and machine-gun fire, as the Germans tried to pick off the survivors: 'According to my wrist-watch, it was now 11.30 am, that is, about four hours since I had been hit... And I have said nothing of the groans and cries about me throughout that time. The ground was thronged with the men of three battalions. Many were the human fragments that must have shot up with those repeated earth-spouts. '

'And then deliverance came -a torrent of shell on the Boche ... A man ran past me, in the right and obvious direction, and was not fired upon ... Getting up, I made for the dear trenches, not without seeing, however, what No-Man's-Land now revealed. Bodies were everywhere, in every posture. Blood had long since blackened in the sun. I shall not forget those blood-stricken dead faces, and the awkward prostration of the instantly killed. These men were filled with the bravest hope at dawn. Now they were unaware that they had ever lived.'

The result: Out of 23 officers and 809 other ranks in 1st Battalion,

The Border Regiment, 20 officers and 619 other ranks were killed, wounded or missing.

In Harold's battalion, 20 out of 23 officers, and 619 out of 809 other ranks were killed, wounded or missing. He wrote this poem:

Now from a trance of sorrow and pain

Before the reeling sun had set,

With torn shirt caked with blood and sweat

I crawled from the tumbled dead -

There where my friend's face, yellow and stark

'Stared at the sun as it were the dark,

God knows I feared and fled.

I wake to walk God's earth again,

Where morning's flowing gold

And the sweet breath caught from grass and flower

Give me more joy in one live hour

Than my heart and soul can hold.

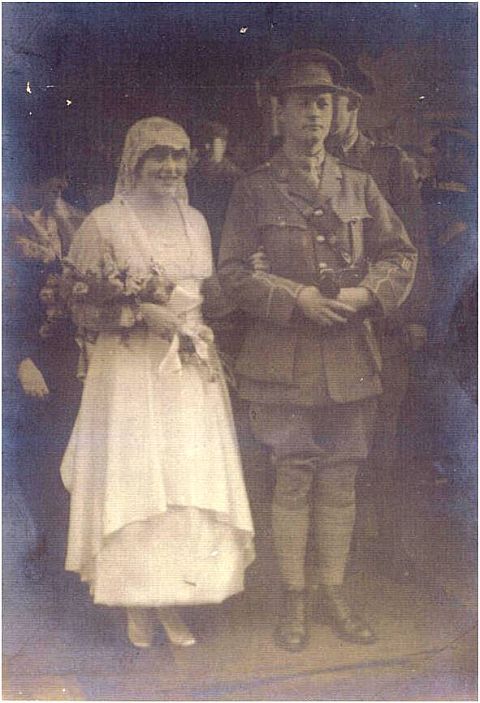

One good thing happened to Harold as an indirect result of the tragedy of the Somme. While recovering from his injuries in a hospital in London, he met a fellow South African, my Grandmother, Margie Anderson, who was a nurse with the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment). They got married a year later.

Wedding day.

After a long recovery and many operations, Harold transferred to the Balloons in January 1918, where he learned to fly helium sausage balloons at the Balloon School in Richmond Park.

July 1918: Balloons

Harold transferred to the 43rd Balloon Section, Royal Air Force, on the Western Front as a balloon pilot. His job was to be winched up in the balloon to a great height, and gather intelligence, such as enemy movements and the positions of their guns; and report what he saw via telephone to the men below.

One day, he was observing in his balloon when a German aircraft attacked: ' ... Archie cracks warningly overhead ... In a moment I am sitting on the rim of the basket, with the [telephone] receiver held to my ear ... Far off there is a little trouble in the sky, but of imminent Boche planes I can see none - simply because my back happens to be turned to the three adjacent balloons flaming down, and a wasp-like plane darting upon me. '

'The words 'Jump, jump" in the receiver coincide with the spiteful wisp of the relevant bullets ... My parachute was a new one and took a little longer than usual to open. But... all was well, save that the belt of my parachute harness had loosened and I had to cling to the rope like a monkey. A glance upward showed the wheeling Boche putting a parting shot into the balloon as it began to crumple in fire. But now I became aware of a new danger - the possibility of being caught by the roaring mass ... I endured fifty terrified heartbeats. However, nothing but flying cinders and flaming tatters of fabric reached me.'

Luckily, Harold landed safely.

Peace

Finally, the war ended. Harold's last entry in his diary was:

'After four and a half years I return to life. With a secret flutter in my heart, and a marvelling diffidence in my step, I disappear once more in the crowds of the world'.

Conclusion

After the war, my grandparents returned home to Grahamstown, where they both lived long, healthy lives. Harold always maintained that he was a peace-lover, and he warned against the glorification of war. Thus I close the diary on the events of a hundred years ago.

Sources

Sampson, H F, unpublished diary of the First World War.

'The regimental Roll of Honour and war record of the Artists' Rifles (1/28th, 2/28th and 3/28th battalions, the London Regiment TF) Commissions, promotions, appointments and rewards for service in the field obtained by members of the corps since 4 August, 1914 to 1917'

(https://archive.org/ details/regimentalrollofOOhighiala).

The London Gazette (18 February 1915),

https://www.the gazette. co. uk/London/issue/29074/supplement/1699.

Shot at Dawn Campaign (online research)

www.telegraph. co. uk/news/1526437/Pardoned-the-306-soldiers-shot-atdawn, etc.).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org