The South African

The South African

'Lord, there is no-one like you to help the powerless against the mighty. Help us, O Lord our God' -

2 Chronicles 14: 11 (NIVUK).

Mosega Koppies

The remnants of the Potgieter trek reached Blesberg from Vegkop, shortly before a new trek, led by Gert Maritz, arrived from the Cape Colony. A form of government was elected, with both men occupying positions of leadership. The Citizen's Council decided to eliminate the threat of Mzilikazi and to retrieve the stolen cattle. A commando, that included local auxiliaries, set off for this purpose to Mosega, via Kommando Drift. The Ndebele were totally surprised and defeated, with 6 500 head of cattle being recaptured. An American missionary station found itself in the midst of the hostilities and the missionaries decided to return with the commando.

Introduction

The last members of the Potgieter trek arrived from Vegkop at Blesberg (Thaba Nchu), a few days before the coming of the Maritz Trek from the Cape Colony (Van der Merwe, 1987, p106). Gert Maritz, who had been a prominent businessman and a respected civil administrator in the town of Graaff-Reinet, was the leader of a large group of family and friends that arrived at Blesberg on 19 November 1836 (Thom, 1947, p103). Both Maritz and Potgieter realised that some form of official government for the Voortrekkers had become an urgent necessity.

A general assembly was therefore conducted in the Potgieter laager on 2 December 1836, where a Burgerraad (Citizen's Council) of seven members was elected by secret ballot. Maritz was chosen as 'President' and Potgieter as 'Legerkommandant' (Army Commander). This management council was elected by using democratic principles and was the first of its kind in South Africa (Thom, 1947, pp104-6). Apart from administrative considerations, the Burgerraad had to attend to matters arising out of the treatment of the Voortrekkers by King Mzilikazi.

Many members of the Potgietertrek were impoverished, if not destitute, when the survivors of the Battle of Vegkop reached Blesberg during November 1836. Their leader, Kommandant Hendrik Potgieter, for example, had lost 5 000 sheep, 300 head of cattle and 100 draught-oxen at Vegkop (Potgieter and Theunissen, 1938, p65). For subsistence farmers, the possession of livestock, especially cattle, implies wealth (Thom, 1947, pp83,109). The Voortrekkers therefore keenly desired to repossess the animals that Mzilikazi had taken from them. They "also yearned for the permanent removal of the threat that his marauding impis presented (VDM, 1986, pp130-1; Thom, 1947, p121).

The Voortrekkers at Blesberg were very much aware of the possibility of another Ndebele attack. On 9 December a rumour of an Ndebele advance reached them. They immediately prepared a laager for defence, but it proved to be a false alarm. Two days later, on the afternoon of 11 December, however, another report was received. It was also taken very seriously by Maritz and Potgieter, and by 13 December they had a well-prepared laager to counter any attack. This rumour turned out to be another false warning. These events prompted the leadership to organise a commando for departure on 20 December, but on that day the weather was unfavourable. Maritz also considered the commando to be below strength. He therefore went south towards late arrivals, to recruit volunteers to accompany the commando. Maritz returned on 29 December, to make final preparations (Thom, 1947, pp121-7).

The advance of the commando

The commando left Blesberg on its way to Mosega in two detachments. The burghers under Potgieter departed on 2 January 1837. A prayer meeting was conducted that evening by Erasmus Smit, the unofficial dominee (minister) of the Voortrekkers. His message was based upon the verse quoted above (2 Chronicles 14:11). The detachment led by Maritz proceeded the following day. The latter group bore distinctive red ribbons around their hats (Thom, 1947, p128). This arrangement raises the question as to who was in overall command.

As mentioned previously, the degree of command and control in a Voortrekker commando is not comparable to that in a modern military unit. The majority of the burghers saw service during the Border Wars in the Cape Colony, but in essence they were civilians looking for a better way of life. They had attached themselves to a leader and would follow him whether trekking or fighting. The dual leadership of the commando should therefore not be surprising. However, it appears as if there was indeed a supreme commander, and it was Maritz. He did not have the military experience of Potgleter, but he was an able leader and was elected to the highest position of the Voortrekker community (VDM, 1986, pp141-5).

The total strength of the commando consisted of 107 Voortrekkers, plus 100 auxiliaries. These men were made up of 40 mounted Griquas under Pieter Dawids, as well as 60 members of the Barolong tribe on foot. The latter were led by Matlaba (Matshabe), a Barolong chief. They were hired to act as herdsmen for the cattle that were to be taken from the Ndebele king. Matlaba also acted as guide, as he used to be a vassal chief of Mzilikazi and knew the route to Mosega well (VDM, 1986, pp137-141).

The commando advanced in a north-westerly direction and crossed the Vaal River at Kommando Drift, not far from the modern town of Makwassie. On their way, they did not find a single kraal or any sign of habitation. At Kommando Drift the wagons were left behind, while the commando continued north-west until it reached the Kuruman-Mosega road. From there it followed the road to Mosega in a north-easterly direction. They therefore approached Mosega on the approved route, not to arouse any suspicion. The leaders were well aware that they were seriously outnumbered and that success depended upon total surprise.

Map of Mosega Mosega

Motsenyateng, the military capital of Mzilikazi, was situated in the Mosega basin, about 10km south of the modern town of Zeerust. It was located in a well-watered, fertile valley surrounded by hills, which is today known as the Little Marico. In February 1836 some missionaries sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions had settled there. The Rev Daniel Lindley, the Rev Henry Venable, and Dr Alexander Wilson, and their wives, had rebuilt a missionary station that had been founded a few years earlier by missionaries of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society (Kotze, 1950, pp124-6). These missionaries were Samuel Rolland, Prosper Lemue and Jean Pierre Pellissier, who had settled there in April 1832, but, during July of the same year, had to flee for their lives, on account of a perceived attack by the Ndebele king's impis. Initially Mzilikazi was in favour of the missionaries settling in his kingdom. He had captured about 60 muskets from the Griquas during the Battle of Moordkop (Massacre Hill) in June 1831 and wanted the missionaries to teach his warriors how to handle them, and to assist him in obtaining more firearms. The Ndebele king's enthusiasm diminished considerably when he realised that they proclaimed a gospel of peace (Pellissier, 1956, pp108,118-119).

Today there is nothing left of Motsenyateng or the missionary station, but the farm where the latter used to be, is still known as Zendelingspost (Missionary's Post). Mzilikazi's complex consisted of the main kraal, about 5 km north of Zendelingspost, and about eighteen to twenty smaller kraals in the vicinity. Here approximately 2 000 warriors lived, being the bulk of the Ndebele king's army. This strategy makes sense, as his largest threats were from the south. Motsenyateng also was the home of Khalipi, the supreme commander of Mzilikazi's impis.

The Ndebele kraals were constructed as accommodation for both people and cattle. A kraal consisted of two concentric circles, made with poles planted in the ground. The inner circle was used as an enclosure for the cattle at night. In between the circles, in an area ranging from about half to one and a half hectares, there would be around 20 to 100 huts, each in the form of hemispheres with a diameter of between 3 and 6 metres. The framework was made of branches that crossed one another rectangularly, and were tied together with grass. This strong framework was covered completely and densely with grass. There was only one small opening for illumination and ventilation. This entrance was usually so small that a man had to crawl in a prostrate position to enter (VDM, 1986, pp153-4).

The attack

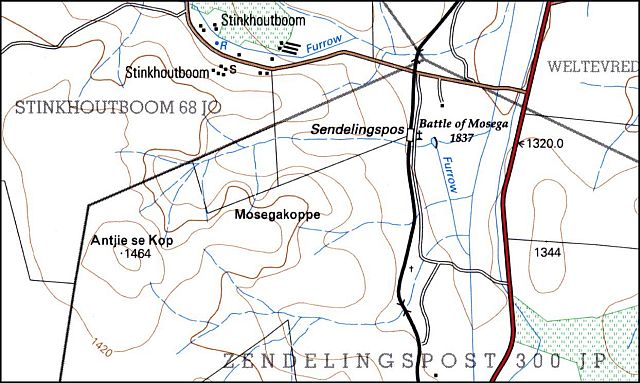

This account of the attack on kraals at Mosega is based in part on local oral tradition, supplied by the Gronum family who had lived in the vicinity since 1855, and recorded by Prof van der Merwe. The commando moved out early on the morning of 17 January 1837, over Antjie-se-kop. Here it split up. Potgieter, with the bulk of the burghers, descended down Groot Kloof (Large Valley) in a northeasterly direction. Maritz initially advanced to the east, descending down the Mosega Koppies, but later turned north. The battle plan was that Maritz would do a frontal and Potgieter a flank attack, both detachments being mounted. They would regroup at the entrance of Groot Kloof, in the vicinity of the later, but currently abandoned, railway siding of Sendelingspos.

The attack commenced at daybreak, which was at 05:00, at a kraal in the proximity of the missionary station. The Ndebele were taken completely by surprise. They were awakened by the firing of the first shots and attempted to escape through the narrow openings of their huts. They fled in utter confusion, while being hotly pursued by the detachment of Potgieter. Another group of Ndebele fled from Maritz and his burghers (VDM, 1986, pp156-9).

Potgieter's detachment attacked the nearest kraal, where Groot Kloof opened up. This happened to be a few hundred metres from the house of the missionaries. Some Ndebele fled towards the house and also to a vleiland (wetlands) behind it in Zendelingspruit (Missionary's Creek), thus drawing fire from the attackers. The missionary station soon found itself involved in a severe fire-fight. Some slugs were stopped by the walls, and one entered through the window where Venable and his wife were lying in bed.

After the first kraal was torched, the commander (presumably Maritz) approached and assured Dr Wilson that they would do the missionaries no harm. He also invited them to leave with the commando, as it would not be safe for them to stay behind. He added that the Voortrekkers intended to do a second attack with a stronger commando against Mzilikazi (Kotz€!, 1950, pp154,168). Following this conversation, he left to re-join the commando.

The Ndebele fled eastwards as far as the current railway line and then turned north. Initially the attack proceeded at a fast pace, sometimes at the gallop. As more and more Ndebele were wakened by the battle noise, they began to provide resistance and the attack slowed down. Meanwhile their huts were being torched, adding to the chaos and slowing down the attack even .further. Some burghers and auxiliaries began rounding up the cattle, kraal after kraal.

At sunrise, three groups of Ndebele converged in the neighbourhood of the modern railway siding, which was a few hundred metres from the home of the missionaries. Here some indunas tried to organise a counter-attack, as neither Mzilikazi nor Khalipi were present. They attempted to execute the proven 'horns of the bull' formation, but by then the Voortrekkers were well aware of these tactics. They concentrated their fire upon the developing horns, until the enemy gave up and fled northwards, in the direction of the modern town of Zeerust (Thom, 1947, pp132-135).

The commando, also moving northwards, attacked kraal after kraal, setting them on fire. The auxiliaries collected the cattle. Some fourteen or fifteen kraals were attacked and destroyed. A number of Ndebele women were either shot or killed by the assegais of the auxiliaries (Kotz€!, 1950, p164). All who could possibly do so, fled in great haste. Details from reliable sources regarding the duration and extent of the attack are scarce and vague. Maritz and Dr Wilson agree, however, that the battle was over between 11:30 and 12:00 (VDM, 1986, pp163-165).

The missionaries

At noon the commando returned to the missionary station. The missionaries were faced with a life-changing decision. Should they leave Mosega with the commando for good, or should they stay behind and face the consequences? There was not much time to make a decision, as the commando was anxious to put maximum distance between it and Mosega before nightfall. The leaders were well aware of the

possibility of a counter-attack by Mzilikazi's impi (VDM, 1986, pp169-172).

If the missionaries chose to remain behind, they would be regarded as being sympathetic towards the attackers. To make matters worse, their home was not destroyed when the huts in fourteen or fifteen kraals were. Mzilikazi had demonstrated an ambivalent attitude towards them, especially since he had discovered that the American missionaries also believed in a God of love and peace. Throughout his life, his policy was to obliterate his enemies from the face of the earth. He even went so far as to forbid his subjects to attend church services (Thom, 1947, pp1356). If the missionaries were to decide at a later stage to leave, they would have had to obtain permission from the king. This could either be granted or refused, at Mzilikazi's whim (Kotze, 1950, pp170-1).

Leaving with the attackers, on the other hand, would mean giving up their dream and their calling, namely to bring the Gospel of Christ to the Ndebele. They had sacrificed everything to do this, including undertaking a dangerous sea-journey from the United States lasting some months, and then a harrowing trip by ox-wagon from Cape Town. On their arrival at Mosega, there had been nothing but the ruins of the French station. They had camped in their wagons until they had built a home while engaging in difficult negotiations with Mzilikazi in a foreign language. In September 1836, all but Dr Wilson had fallen ill from rheumatic fever, and the doctor's wife had died of the illness and was buried near the missionary station (Kotze, 1950, pp170-1).

The missionaries at Mosega realised that they would not be able to continue their work among the Ndebele, following the Voortrekker attack. They were also aware that the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions had established another missionary station at Port Natal in March 1836, to work amongst the Zulu of King Dingane. They therefore decided to return with the commando, in the hope of eventually joining their colleagues at Port Natal (Kotz€!, 1950, pp155, 168-172). In order to do this, they had to pack two ox-wagons within an hour, leaving behind a substantial part of their earthly possessions, including the library of Venable. Meanwhile, some of the hungry burghers helped themselves to biltong (raw meat) that the missionaries had hung out to dry, as well as vegetables from their garden (VDM, 1986, p165).

The return journey

What an extraordinary spectacle the returning party must have been! It consisted of horsemen armed with guns, footmen armed with shield and assegai, 6 500 cattle and some sheep with unarmed herdsmen, as well as the two ox-wagons with the five missionaries and their two children. The commando trekked through the entire first night without taking a break. They rested for an hour at 11 :00 the next morning, after which they trekked on until late the following night. Dr Wilson, who was the healthiest of the missionaries, frequently had to act as touleier (leader of the team of oxen), something that was entirely new to him.

The commando followed the route by which it came, but the large number of animals slowed down the pace of movement. At night the men struck camp, with the animals surrounded by herdsmen. The noise made by the thousands of animals was deafening. Sometimes migrating antelope were mistakenly regarded as an advancing Ndebele impi, adding to the anxiety of some, especially the missionaries.

The latter had very little food, but Maritz took great pains to make their journey as comfortable as circumstances permitted (Thom, 1947, p137).

After a week, they reached Kommando Drift, to find the Vaal River in flood. This would delay the crossing, but was regarded as a blessing in disguise, as the threat of a pursuit would be diminished. The animals had to swim across, and a few auxiliaries drowned during the crossing. The men built a raft of tree trunks to ferry the missionaries across the river. When they arrived on the other side, they and their possessions were soaking wet. That night it began to rain heavily.

The commando made a halt at Kommando Drift for a few days, while the remainder of the cattle were brought across the river. The burghers butchered an ox to supplement their rations. Then the commando split up, with some mounted men leaving for Blesberg, while others with the wagons and animals followed behind. Maritz and the missionaries also proceeded at a slower pace. For the rest of the journey it rained virtually continuously, making it necessary to replace some trek ropes with the braking chains. The missionaries eventually reached Blesberg on 31 January 1836, where they were welcomed by the Rev Archbell and the Wesleyan missionaries with extraordinary kindness (VDM, 1986, pp172-3).

Mosega Monument Aftermath

The number of Ndebele killed cannot be determined accurately. The American missionaries estimated it to have been between 200 and 400 (Kotze, 1950, p169), whereas Maritz, who might have been in the best position to make an assessment, gave a number of 400. No Voortrekker was killed or wounded, but two auxiliaries lost their lives. One had crept into an Ndebele hut to see what he could appropriate, but had been slain by the owner. Another was shot by a Voortrekker, who had mistaken him for an Ndebele warrior (VDM, 1986, p168).

A preliminary redistribution of the cattle was conducted at Kommando Drift. This was done to compensate the auxiliaries for partaking in the commando. At Blesberg a second redistribution occurred, this time to recompense the members of the Potgieter trek for their losses incurred at the Vaal River and Vegkop. When this had been completed, the remaining cattle were divided between the members of the commando (VDM, 1986, pp174-7). Unfortunately, a difference of opinion arose between Maritz and Potgieter, regarding the division of the cattle.

Maritz had assured Dr Wilson that the Voortrekkers would return with a stronger commando to drive Mzilikazi out of the area and to eliminate the threat that his impi represented. Events at Blesberg delayed this second commando considerably. Among these was the arrival of Piet Retief with his trek from the Winterveld region of the Cape Colony. On 17 April 1837 Piet Retief was elected as 'Goewerneur en Opperbevelhebber' (Governor and Commander-in-Chief) for the Voortrekker community .. Retief and the newly formed Political Council had various other urgent matters to attend to, among them constitutional considerations, relations with the neighbouring tribes, as well as with the British Government, organisation of the church and the ultimate destination of the trek (Thom, 1947, pp150-6).

The second commando eventually set out during the last months of 1837 in the so-called 'nine-day campaign', that also became known as the Battle of Kapain. This campaign surely has to be one of the poorest documented conflicts in South African military history. Potgieter and Theunissen give a detailed account, but their book was written a century after the events and is largely based upon oral narratives of unknown origin (Potgieter and Theunissen, 1938, pp79-95). They provide numerous particulars, including the route of the commando and a map indicating the individual battlesites. These are described in detail, complete with dates. Van der Merwe had serious doubts about the general credibility of their descriptions. There is no doubt however, that the Ndebele were heavily defeated by the Voortrekkers during this campaign (VDM, 1986, pp220-6).

After being dispersed by the Voortrekkers, Mzilikazi and his remaining followers fled from the Marico to the eastern parts of the modern Botswana. From there he settled during 1840 in what became known as Matabeleland, in the present Zimbabwe (VDM, 1986, pp227 -240). Meanwhile, the Voortrekkers trekked over the Drakensberg into Natal, where they encountered Dingane, king of the Zulu. Following the disastrous Battle of Italeni (1838), Potgieter and his trek returned to what would later be known as the Transvaal, where he had further confrontations with Mzilikazi (VDM, 1986).

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Louis Retief for assistance with this article.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page

Kotze, D J (Ed), Letters of the American Missionaries, 1835-1838, VRS Publication No 31 (Cape Town, The Van Riebeeck Society, 1950).

Pellissier, S H, Jean Pierre Pellissier van Bethulie (Pretoria, J L van Schaik, 1956).

Potgieter, Carel en Theunissen, N H, Hendrik Potgieter, (Johannesburg, Afrikaanse Pers Beperk, 1938).

Thom H B, Die Lewe van Gert Maritz, (Kaapstad, Nasionale Pers Beperk, 1947).

Van der Merwe, P J, Die Matabeles en die Voortrekkers, Argiefjaarboek vir Suid-Afrikaanse Geskiedenis, Nege-enveertigste Jaargang - Deel II, (Pretoria, Die Staatsdrukker, 1986).