The South African

The South African

Introduction

On 8 January 1806, the Battle of Blaauwberg was fought just outside Cape Town. This battle, arguably the most important in South Africa, was destined to change the course of South African history. Its outcome has triggered many events and its aftershocks are still felt today.

The battle has remained obscure for mainly political reasons and modern authors have often misinterpreted the available information. The cannon used at Blaauwberg fall into this category. The contemporary British references, notably those of Major-General Sir David Baird, Captain Dugal Carmichael and Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Wilson mention 23, 22 and 30 Batavian cannon respectively at the battle, whereas the Batavians themselves reported only sixteen. This is understandable; whereas the British would want to overstate the number so as to enhance the battle's prestige, the Batavians would like to understate it. But how many cannon did the Batavians actually have? Sources tend to agree on the number of cannon the British had at the battle.

There are also modern reports that four of the Batavian cannon at Blaauwberg were Indonesian lantakas. This is doubtful as lantakas are small calibre weapons and several found in Holland have a maximum bore of 53mm (one-pounder). They are heavy and cumbersome and not really suited for mobile warfare, the role they would have been expected to play at Blaauwberg.

This article attempts to clarify some of the misconceptions and put forward the most likely number of cannon that were present at the battle, but it must be understood that there is no final definitive answer, as the relevant information was not accurately recorded at the time.

Determining the number of cannon

There are no problems concerning-the number of cannon that the British had at the battlefield as a quick analysis of other sources such as maps and manpower records confirms there were eight. According to the official report from Lieutenant-General Janssens to Right Honourable Majestic R J Schimmelpennick, the Prime Minister of the Batavian Republic, prepared some two months after the battle, the Batavian forces had the following cannon and related equipment at the battle (Leibbrandt, p 110):

Two 24-pounder howitzers, six 6-pounder field cannon, two 3-pounder field cannon, six one-pounder field cannon, and thirteen caissons. This gives a sum total of sixteen pieces of artillery, substantially lower than the numbers claimed by the British sources above. We are now left with the more difficult task of determining which is correct. It is possible to conclude which total is correct but we first need to consider the following information in detail: Manning of the Batavian cannon, horses required and information sources.

Manning of the Batavian Cannon

During the Napoleonic Wars there were three main branches of artillery: Siege (generally heavy calibre cannon lacking mobility), Foot (mid-range calibre cannon generally used to hold key points on the battlefield and more mobile than siege artillery), and Mobile or Horse (a relatively new branch of artillery comprising generally lighter calibre cannon designed to keep pace with the very mobile mounted units on the battlefield). The earliest known British reference work on this subject is The Artillerist's Companion. There are later books, notably Adye's The Bombardier and Pocket Gunner.

According to The Artillerist's Companion (Fortune, p 5), the following manpower was needed to man the cannon in the field (excluding the commanding officers in cases where there were two or more guns, the men required to operate the ammunition supply trains, and the musicians):

| Table 1 - Return of the Number of Men (Light Guns) - Foot Artillery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duty | 5¼ howitzer | 6-pounder | 1-pounder* |

| Superintend | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| To Steer | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prime & Fire | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Load & Ram | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Drag Ropes | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Ammunition | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 12 | 14 | 6 |

as it is not included in The Artillerist's Companion but based on manpower requirements for the 3-pounder (see Table 2).

| |||

The formation of the horse artillery was, by the time of Fortune's book, a little-known branch. However, there are other records, notably sketches, detailing manpower requirements for light 3-pounders (Caruana, p 19).

| Table 2 - Return of the Number of Men - Horse Artillery | ||

|---|---|---|

| Duty | 3-pounder | 1-pounder |

| Superintend | 1 | 1 |

| To Steer | 1 | 1 |

| Prime & Fire | 1 | 1 |

| Load & Ram | 2 | 2 |

| Drag Ropes | 2 | 2 |

| Ammunition | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 8 |

Using Lieutenant-General Janssens' report, which states the number of cannon, we can summarise the manpower requirements as follows:

Mobile Artillery Unit: This had two 3-pounders, which, according to the above, would have required sixteen men to man them, as well as the commanding officer, Lieutenant Pellegrini, a non-commissioned officer, and the musician (bugler or halfmaanblazer), giving a total of nineteen men. According to records, the mobile artillery unit had nineteen men (Liebbrandt, p110).

Javanese Artillery Unit: This was a foot artillery unit which had six 1-pounders. Therefore the return of manpower would be 48 men. Lieutenant Madlener of the 5th Artillery was seconded to this unit at the battle. There would also have been a Malay officer, three non-commissioned officers and a musician, giving a total of 54 men. According to the records (see Leibbrandt, p 110), the Javanese Artillery had a total of 54 men, comprising one lieutenant, three sergeants, six corporals, one musician and 43 men.

The 5th Artillery Regiment: This foot artillery regiment had two howitzers and six 6-pounders. The command structure would have been slightly different. Just before the battle this regiment was divided into three separate companies, which were later divided into four companies. The cannon were positioned well to the front of the line with the caissons behind the line. The manpower would have been: For the howitzers, 24 men, and the 6-pounders, 84 men, as well as three musicians, four senior officers, four junior officers, eight non-commissioned officers, one NCO musician, and eight extra ammunition carriers, giving a total of 136. According to the records (Liebbrandt, p 110), the 5th Artillery had four captains, five lieutenants, 25 noncommissioned officers, two cadets, three musicians and 102 rank and file, giving a total of 141 men. (It is interesting to note that there are five more men in the records than the theoretical calculated number and, of those, one is a lieutenant and four are corporals. It is possible that the lieutenant may have been Madlener, who, with the four corporals, was seconded to the Javanese Artillery.

Horses

Another way to determine the number of cannon at the battle is to look at the record 'of the number of horses used. There were 149 horses assigned to the artillery train, which had two officers and eight commanders, excluding the nineteen horses assigned to the mobile artillery (Liebbrandt, p 110). On good roads, the number of horses normally required per 6-pounder was two, and per howitzer, three (Fortune, p 6; Muller, p179). However, as the roads in the area were poor and the cannon were positioned on deep, sandy soil, additional horses would have been needed. Janssen's report mentions the loss of six horses with the 6-pounder (Liebbrandt, p 7), which shows that each artillery piece needed four extra horses. There were thirteen ammunition caissons, which would normally have required three horses each, but again it may be assumed that due to the terrain there were three extra horses.

| Table 3 - Return of Horses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | Artillery Piece | Number of Pieces | Horses | Extra Horse | Per Unit | Total Horses |

| Mobile | 3-pounder | 2 | - | - | 19* | |

| Javanese | 1-pounder | 6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 24 |

| 5th | Howitzer | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Artillery | 24-pounder | |||||

| Artillery | 6-pounder | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 36 |

| Artillery | Caisson | 13 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 78 |

| Artillery Train | Officers # | 2 | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| Total | 171 | |||||

# Possibly not mounted.

| ||||||

Return of Ordnance Report

Immediately after the battle, General Janssens informed Lieutenant-Colonel van Prophalow in Cape Town of his loss and ordered all the horses and other military equipment to be sent to the Hottentots-Holland headquarters. Van Prophalow then sent everything requested. The report mentions that two howitzers and four 3-pounders were sent from the Castle (Liebbrandt, p 130).

The Batavian army had a roll call on the morning of 9 January, when Adjutant Rancke confirmed the number of cannon as fifteen. According to General Janssens and others, one 6-pounder and a caisson had to be left on the battlefield. These were obviously captured by the British (Liebbrandt, p 113). Adjutant Rancke, in his journal entry dated Friday, 10 January 1806, states that, on their arrival at the Hottentots-Holland headquarters, Major Horn had brought a further two howitzers (Liebbrandt, p 9). Based on this information the number of cannon held by the Batavians at Hottentots-Holland can be summarised as follows:

| Table 4 - Batavian Cannon in the Hottentots-Holland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannon Type | At Battle 8 January | Lost in the battle | Sent from Simon's Town | Sent from the Castle | Total |

| 1-pounder | 6 | - | - | - | 7 |

| 3-pounder | 2 | - | 4 | 6 | |

| 6-pounder | 6 | 1 | - | - | 5 |

| 24-pounder howitzer | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 16 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 25 |

| Table 5 - Batavian Field Guns in the Return of Ordnance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannon Type | In Store | Serviceable | Repairable | Non Serviceable |

| 1-pounder | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| 3-pounder | 6 | 6 | - | - |

| 6-pounder | 13 | 8 | 1 | 4 |

| 24-pounder howitzer | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| Total | 29 | 24 | 1 | 4 |

Although there are two anomalies in this document - namely, the total of 1-pounder and 24-pounder howitzers handed over - this document concurs mostly with Janssens' statement regarding the number of cannon on the battlefield. Overall, the Batavian records appear more reliable. However, in examining the sources, an interesting question emerged. Major Spicer's 'Return of Ordnance' report records five 1-pounders, yet the Batavians claim they had six at the battle and that they lost one 6-pounder (which was spiked) and a caisson. Lieutenant-General Ferguson, on the other hand, claims that they captured two cannon. Did the Batavians therefore actually lose two cannon, one 6-pounder and one 1-pounder?

The analysis of the deployment of men and horses above proves that there could only have been sixteen Batavian field pieces at the battle. Why were the reports written by the British officers so different? My hypothesis is as follows:

Major-General Baird: Is it sheer coincidence that Baird's despatch of 12 January 1806, stating that 23 cannon (WO 1/342, P 7) were on the battlefield, matches the number of cannon handed over to the British on the capitulation of the colony on 18 January 1806? My theory is that when Cape Town capitulated on 10 January, Baird would have had access to the Castle records, which would have indicated that there were 23 serviceable cannon at the Castle prior to the battle, not including the two howitzers from Simon's Town.

Captain Dugal Carmichael: Unfortunately, the date of Carmichael's letter is unknown, but by tracking his movements, we can be fairly certain that it was penned either in late January or early February. After the battle, Carmichael was sent to Stellenbosch. There he received orders to march to Paarl and then onto Tulbagh, where he arrived on 20 January. He returned to Stellenbosch towards the end of January and finally was sent to Simon's Town. In theory, Carmichael could have found on his return that the total number of cannon captured was 24. As he was stationed in Simon's Town, he would have known that two had come from there. This could explain why he stated that the number of cannon at the battle was 22.

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Wilson: Wilson did not participate in the battle as he had been sent to Saldanha. He arrived in Cape Town on the date of its capitulation on 10 January 1806 and was present when Janssens surrendered the colony on 18 January. As he was due part of the prize money, he must have been well aware of the 29 field cannon on Major Spicer's 'Return of Ordnance' report, plus the one captured (the latter which should not have been included as it was now the property of the 71 st Regiment). This explains his total of 30. There are several errors in his journal record of the battle which can be attributed to his having received second-hand information.

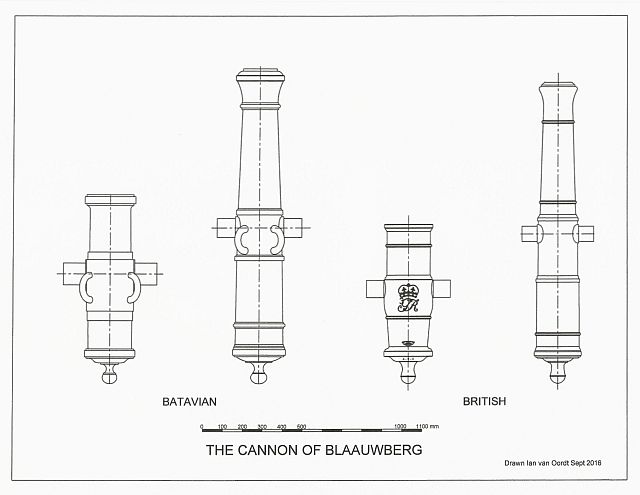

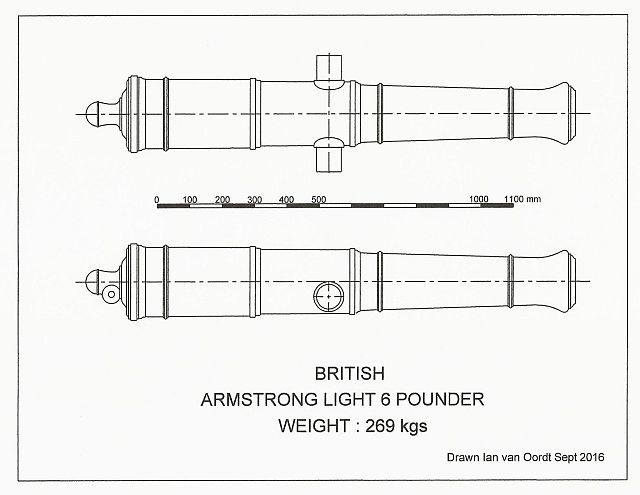

Types of Cannon - British

It is not too difficult to work out the type of cannon the British used at Blaauwberg. Most sources refer to six 6-pounders, but, from the 'bill of lading' for the transport ship, Walker, and others (see WO 1/341, P 99), it is very clear that the cannon were of the light type. The cannon were assigned to the 5th Battalion, Royal Foot Artillery, Clason's and Watson's Company. At that time, the typical light 6pounder pieces were of the 4 ft 6-inch Armstrong pattern and were most likely mounted on Congreve bracket carriages (see Rudyerd, plate 39), as the more modern Desagulier block trail carriages were reserved for the horse artillery and the European theatre.

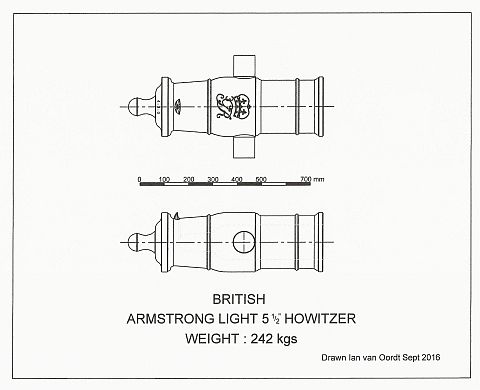

The two howitzers in British use are much more difficult to pin down. It is fairly certain that they would have been the lighter 5½-inch and most likely the Armstrong/Frederick pattern, as the heavy 5½-inch would have been difficult to move over the sandy tracks by manpower alone. The carriages were most likely of the Congreve bracket type (WO 55/1194, P 52), as these were not completely phased out in the colonies until 1811 (Caruana, 1982, p 128).

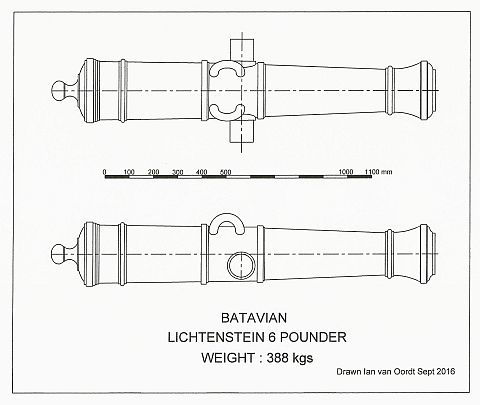

Types of Cannon - Batavian

The identification of the Batavian cannon is considerably more complicated, as Holland was never really considered a military power and, as such, never developed an artillery system, or, if they did, no treatise was ever written about it. They did, however, have a number of foundries in several places capable of producing bronze cannon, but these were mostly of the naval type (Roth, p 52).

An historical perspective

At the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, countries that were able to cast bronze cannon included Austria, England, Prussia, Russia, Italy (Piedmont) and Holland. To understand the origin of Batavian artillery, we have to look at Dutch history. Holland was the first country in Europe to experience a revolution against the rule of the 'stadholder' or monarch, from 1781 to 1787. This Patriot Revolt or 'velvet revolution' was finally suppressed with the help of the Prussian Army. In consequence and in fear of their lives, the Patriots were forced underground, some seeking refuge in France (Schama, pp 64-135). At the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Patriots requested, and were given, French aid. This led to the French occupation of the United Provinces of Holland in 1795, and thus the Batavian Republic was born.

One of the military gunfounders who supplied the United Provinces of Holland was located in the town of Michelin, just north of Brussels. When the country was under Habsburg rule, the Austrians ran a foundry there, called Imperial Bohrwerke (Dawson, p 32; Kennard, p 67). In the late 1780s, Austria closed the foundry. The Austrian Lichtenstein M1753 cannon, developed in 1753 and improved over the years was, at start of the French Revolutionary Wars, still one of the most advanced artillery systems in Europe (Hollins, p 10). During the French Revolutionary Wars, a large number of Austrian cannon were captured and several French regiments were entirely equipped with them. The Batavian Republic, which was allied to France, would no doubt have obtained some captured Austrian pieces for its artillery requirements (Dawson, p 136). It is interesting that during our extensive search of the Archives in The Hague, we never found any documents that related to the supply of new cannon pieces from 1802 onwards. We did find documents detailing the cannon stored at various armouries as well as documents detailing the supply of cannon balls from the foundry of Jean Maritz in The Hague.

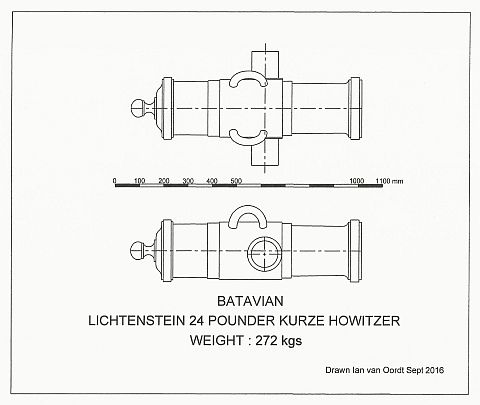

Clues in the 'Return of Ordnance' report Interestingly, Major Spicer's 'Return of Ordnance' report includes a number of French calibre field cannon that lacked limbers and were thus unsuitable for use (WO 1/342, P 100). This helps to confirm the French as a supply source for Batavian artillery. The report also gives details of the length and weight of a 24-pounder howitzer, indicating that it was the light howitzer.

The howitzers

The French, like the British, specified their howitzers in the nominal size of the bore. The Austrians, by comparison, specified the size of a howitzer by the effective poundage of an iron shot in a stone shot density. Thus the 24-pounder would, in fact, be called a 7-pounder (Dawson, p 39).

Adjutant Rancke records the two howitzers as 24-pounders. Major Spicer, who was familiar with the British nomenclature, should have recorded the howitzer in the 'Return of Ordnance' report in terms of its bore size (the 24-pounder howitzer bore is very close to 5½-inches) but he did not; this then is a clue to the pattern of the howitzer.

The 3-pounder

Another observation concerns the 3-pounder used by the Batavian Horse Artillery. By this stage of the war, Britain and France had abandoned the use of the 3-pounder in favour of the much harder-hitting 6-pounder for their horse artillery. The extra barrel weight combined with new developments in carriage design (Gribeauval for the French and Desagulier for the British) did not seriously hamper mobility; in fact, the new Desagulier carriage was so successful that there was an immediate demand for it to be supplied to the foot artillery. The extra hitting power and increased range had proven effective in battle and far outweighed the slight loss in mobility. Austria, whose doctrine in the use of artillery was still far behind that of Britain and France, was the only European nation still to use 3 and 1-pounders. This is the next clue as to the origins of the Batavian artillery.

Schrotbüchsen

There is an ammunition type which is found only in Austrian artillery handbooks (Smola, p 548). This is a cased shot enclosing 21 cast iron balls of 32 loth (560g weight) each, arranged in three tiers of seven balls per tier (Dolleczek, p 308). The shot, known as 'Schrotbüchsen', loosely translated as 'shot bus', was exclusively used in 'kurze Haubitzen' or light howitzers; The British equivalent is known as 'grape' or 'quilted grape'. Iron shot artefacts recovered from the battlefield match the weight required for a 24-pounder light howitzer Schrotbüchsen round.

My visit to Soesterberg

In the course of my special tour of the Dutch Military Museum at Soesterberg, the curator, Dr Louis Sioos, arranged a special visit to their warehouse to view their full collection. It was unfortunate that, at the time, their examples of 6-pounders were out on loan, but amongst their collection was a 3-pounder field cannon of the right period. The carriage is new but the resemblance to an Austrian M1753 Lichtenstein piece was unmistakable (see Dolleczek, p 295, figure 120). Lantakas ?

The use of lantakas has been attributed to the Javanese Artillery Regiment. Apparently after the battle a Mrs Marie Koopmans de Wet approached the commanding officer at the Castle to have four lantakas returned to her. This has led some researchers to suggest that they were at Blaauwberg and to postulate that it would make sense for the Javanese Artillery to have used them. However, the use of lantakas poses additional questions:

There were six 1-pounders at the battle. Most lantakas in South Africa have a bore of approximately 32 to 36mm, making them ¼-pounders. From a military perspective, this calibre of cannon would not have had sufficient hitting power. The 'Return of Ordnance' report dated 26 January 1806, lists the four lantakas as 1-pounder brass swivels, but they are not mounted. The Javanese Artillery opposed the British landings at Melkboschstrand on 6 January 1806. This area was covered by white sand dunes and is not readily accessible to wagons or cannon, so light and manoeuvrable cannon would have been preferred. During our visit to Holland, I inspected a number of lantakas, some of which were 1-pounders. They were at least 2 metres in length with a calculated weight of 195 kg and generally not suitable as mobile artillery. The surprise of this trip came during my visit to the Dutch Military Museum at Soesterberg. In their colonial field cannon collection, was an example of a 1-pounder. This piece was not a lantaka.

My conclusion

The conclusion that I arrived at is that the British artillery pieces at the Battle of Blaauwberg were two Armstrong pattern light 5½-inch howitzers on Congreve bracket carriages and six 6-pounder light Armstrong 4 ft 6-inch pattern cannon on Congreve bracket carriages. The Batavian pieces at Blaauwberg were most likely either actual or Dutch copies of the Lichtenstein pattern (Dolleczek, p 294):

two 24-pounder Austrian M 1795 short pattern howitzers on bracket carriages;

six 6-pounder Austrian M 1753 pattern cannon on bracket carriages;

two 3-pounder Austrian M1753 pattern cannon on bracket carriages;

and six 1-pounder Austrian M 1780 pattern Tschaiken cannon.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org