The South African

The South African

The Peace of Vereeniging, 31 May 1902 and the amnesty

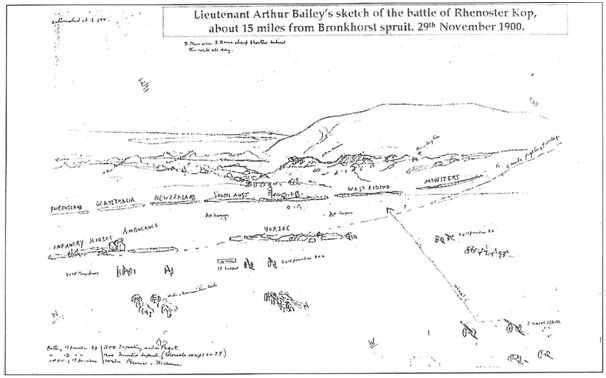

Peace in the Anglo-Boer War did not come easily. It seemed to be more difficult to stop the war than to start it. Peace had been a long time coming. Early in February 1901, it seemed that an opportunity for negotiation had arisen. General Louis Botha's night attack at Bothwell (Lake Chrissie) had been beaten off, although Major-General Horace Smith Dorrien had lost so many horses that pursuit was only half-hearted. General Christiaan de Wet's invasion of the Cape Colony, in company with the Orange Free State President Marthinus Steyn, was also being beaten back.

Mrs Botha, living in Pretoria, was given a letter to send to her husband. A meeting with the British Commander-in-Chief, Lord Kitchener, was proposed for the purpose of arranging terms of peace. Everything was up for discussion 'except that the question of independence of the two republics was not to be discussed in any way'. This, of course, was Botha's opening gambit when he and Kitchener met at Middelburg on 28 February 1901. Kitchener refused to discuss this point, but, nevertheless, details of a possible settlement were discussed in a friendly and reasonable spirit. After the meeting, a draft letter was sent by British High Commissioner Lord Alfred Milner to the British Government who returned it for Kitchener to send a final version to Botha on 7 March 1901. With Botha's letter of 16 March, the Boers declined to negotiate further (Chilvers, Vol V, 1907, p183).

Another year would pass before there was a further development that was to lead eventually to the Peace of Vereeniging. The Boers had sent a three-man deputation to Europe in March 1900, and they had been given full powers to canvass support for the Boer cause but were acknowledged only by the government of the Netherlands. In January 1902, the Dutch Government proposed that they would act as a neutral power to mediate a peace agreement. The Boer peace delegates were to be sent to South Africa to deliberate with their leaders in the field. On their return they would be put 'in communication with the British government and given facilities for the conduct of negotiations in Holland'. (The members of this deputation were Abram Fischer, J B Wessels and A D W Wolmarans, all executive members of their respective governments).

Intervention by a foreign power was clearly not acceptable to Lord Lansdowne, the British Secretary for War, acting on behalf of the British Government. Nevertheless, Kitchener was empowered to send a copy of all the correspondence relating to this matter to the Transvaal Government, which he did on 7 March 1902, but without explanation or comment of any sort.

The Acting President of the Transvaal, Schalk Burger, replied that he was 'desirous and prepared to make peace proposals' but indicated that he needed to meet with President Steyn of the Free State 'to enable us to make a proposal jointly' (letter from Acting President Schalk Burger to General Lord Kitchener, 10 March 1902). The Acting President was met at Balmoral Station by a special train and taken to Kroonstad. Kitchener had been sent a telegram by Burger to be forwarded to Steyn, but the British commander responded that 'it is ... not easy for me to communicate with him, especially as he does not at present make a prolonged stay in any part of the country' (letter from General Lord Kitchener to Acting President Schalk Burger, 18 March 1902).

From Kroonstad, two dispatch riders, Robberts and Hattingh, were sent out to find President Steyn. He was with General Koos de la Rey at Zendelingsfontein, west of Klerksdorp, undergoing treatment for his eyes by de la Rey's Russian doctor, Gustavus von Rennenhampf. (See De Villiers, Vol II, 2008, pp167-170, for details of President Steyn's illness).

Steyn suggested 'Klerksdorp or Potchefstroom or any farm in that neighbourhood which His Excellency Lord Kitchener may consider most suitable' for a meeting with the Transvaal government. Klerksdorp was confirmed as the venue and the first meeting took place on 9 April. After three days of discussions, it was agreed that they should meet with Kitchener in Pretoria so as to put forward their proposals and they arrived there on 12 April. Both sides presented their views, the upshot being that the Boers would elect thirty representatives from each of the two republics to meet in Vereeniging to finally negotiate an agreement leading to a cessation of hostilities.

Proceedings began on 15 May 1902 in a large tent outside the town. The discussions were tortuous with so large a number of representatives with widely divergent views. Many considered that they should (and could) fight on for at least another year, but others thought that they had reached the bitter end (Kestell and van Velden, The Peace Negotiations, 1912, give full details of the proceedings of the meetings at Klerksdorp, Vereeniging and Pretoria). Finally, a draft peace treaty was telegraphed to the British Government, who responded on 28 May with their proposal. General Botha asked whether there would be 'any objection to the delegates deleting some clause or other from the proposal now submitted by the British Government?' but Lord Milner replied 'there can be no alteration, there must simply be a reply of "yes" or "no'" (Kestell and van Velden, 1912, p136).

Very broadly, the proposals were much as Kitchener had discussed with Botha the previous year at Middelburg, but codified with clauses for each of the conditions. The surrender of burgher forces, the return of prisoners-of-war and a number of other conditions were laid down in ten clauses with a further statement describing the payment of reparations.

On Thursday, 29 May, the proposals were put to the Boer delegates for them to decide on one of three actions - to continue the struggle, to accept the proposals of the British Government or to surrender unconditionally. After further deliberation, they gave the 'yes' reply, albeit reluctantly, meeting the British deadline of midnight on 31 May.

Clause 4 of the proposals read as follows and caused some discussion at Vereeniging as to what was meant or implied: 'No Proceedings, CIVIL or CRIMINAL, will be taken against any of the BURGHERS so surrendering or so returning for any Acts in connection with the prosecution of the War. The benefit of this Clause will not extend to certain Acts contrary to the usages of War which have been notified by the Commander-in-Chief to the Boer Generals, and which shall be tried by Court Martial immediately after the close of hostilities.'

During these final deliberations, General S P du Toit of Wolmaransstad asked Botha to clarify the meaning of the clause, asking, 'May I know what acts are here referred to?' Botha then notified the meeting that Kitchener had communicated informally to him that the three persons concerned were:

'Mr van Aswegen [sic] for the shooting of Captain Mears [sic]; Mr Celliers for the shooting of Capt Boyle; and a certain Muller for the alleged murder of a certain Rademeyer in the district of Vrede. These three persons will have to stand their trial on the conclusion of peace' (Kestell and van Velden, 1912, p141). The names of van As and Miers are misspelled.

Kitchener told Botha that these three alleged murders 'had attracted much attention in England, and that the British Government. .. did not see their way open to leave these three cases untried.' On a later occasion, Kitchener repeated, in the presence of both Botha and General Smuts, that only these three would be excluded from the benefit of Clause 4. General George Brand, son of former President Sir John Brand of the Orange Free State, asked why these names were not inserted in the peace proposal. General Hertzog explained that the British Government had required that there could be no alterations made.

General Christiaan de Wet was not satisfied with this, saying that they had only the word of Lord Kitchener and that 'it is not down in black and white, that the three persons mentioned will be the only exceptions'. General de la Rey explained that 'only the three persons mentioned are excluded ... and because we were afraid that there might be more cases, General Botha went and satisfied himself' (Kestell and van Velden, 1912, p142).

At the peace conference, Kitchener told Louis Botha that the British Government required the three alleged murderers to stand trial immediately after the cessation of hostilities. It appears that the Boer leaders had little option but to agree to terms which made provision for the three burghers to stand trial. Conceivably they did this so as to avoid any more burghers being prosecuted for 'crimes against the usages of war'. Shortly after the conclusion of the peace, Salmon van As was tried and executed, even though Botha had assured him that nothing would happen to him. Louis Slabbert, who was merely an accessory to van As's actions, was also prosecuted and sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour.

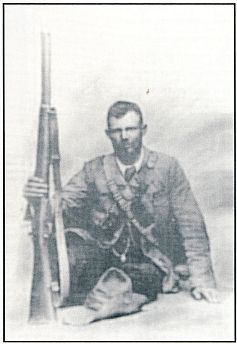

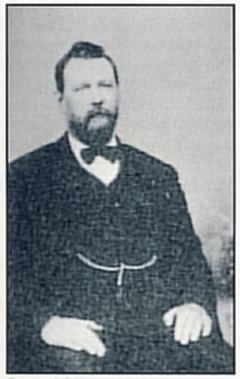

The case of Salmon van As

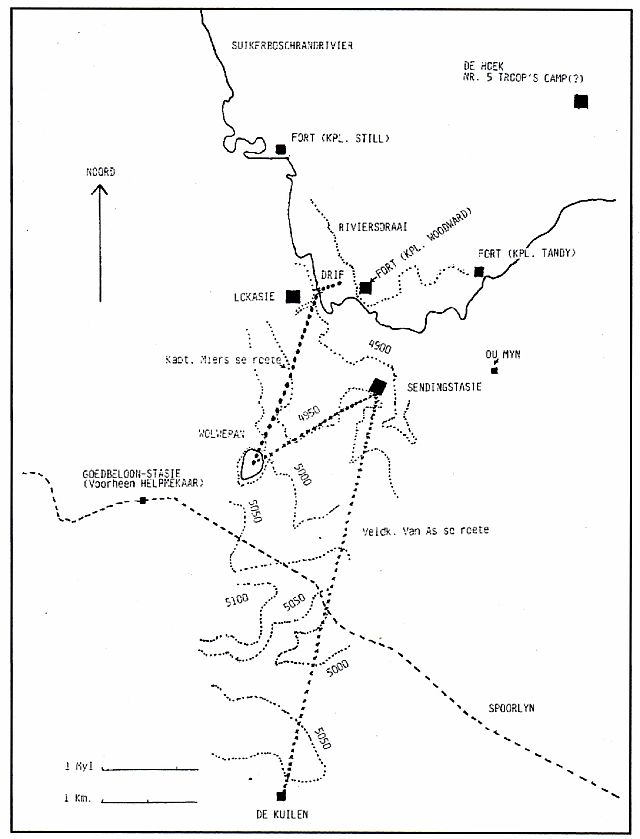

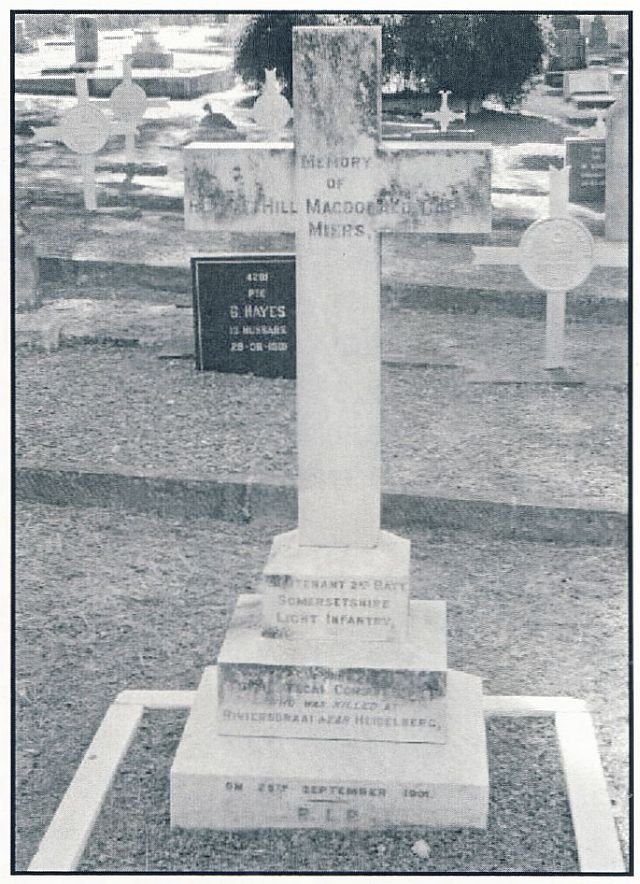

There are a number of published accounts covering the case of Assistant Field Cornet Salmon van As. On 25 September 1901, Van As shot Captain Ronald Miers of the South African Constabulary (SAC) near the Wolwepan, a natural pan of water south of the Suikerboschrand River, not far south of the town of Heidelberg. (Lieutenant Miers of the Somersetshire Light Infantry had transferred to the SAC, with the rank of captain.) Wolwepan is a small crater about 800 metres in diameter and 20 metres deep, always filled with water to a certain level, and fed from the strata beneath. It was an ideal place to keep watch on the police posts along the spruit as they and their horses were hidden from sight in the crater. The Wolwepan is four kilometres from the Suikerboschrand River, and a similar distance from de Kuilen, in the south.

The confrontation between Miers and van As occurred a short distance north-east of the Wolwepan. The SAC took to the field in May 1901 and the area around Johannesburg and Pretoria, supposedly completely cleared of Boer commandos, was protected by a series of police posts. South of Heidelberg there was a line of small forts along the Suikerboschrand River, which is scarcely more than a spruit or stream in that area. Major J Fair in Heidelberg was in command of 'C' Division of the SAC posted to man this line. Captain A Essex Capell was the officer in charge of the line and had his command post on the farm, De Hoek. Captain Miers was in command of a number of forts, each manned by a corporal and a few men. It seems to have been his practice to ride out to Boers whom he had seen in the distance, perhaps with a white flag, to talk with them and to persuade them to lay down their arms. He was reputed to have convinced a number of Boers to stop fighting. (Louis Siabbert's 1953 account to his daughter, Mrs Breitenbach of Ohrigstad, is quoted by H J Jooste in 'Veldkornet Salmon van As' in Christiaan de Wet Annale, 6). The Boer commando, which was still in the area in September 1901, commonly made use of the Wolwepan, where they kept watch on a line of SAC posts along the Suikerboschrand River.

The fatal encounter

On 25 September 1901, Corporal E H Woodward of the SAC, who was stationed in one of the forts to the north of the Wolwepan, reported that he saw '7 or 8 mounted Boers appear on the skyline to our front'. Woodward said that they had a white flag and three of the party advanced on foot 'slowly, making a great display with the white flag'. He was reluctant to go out towards them but Corporal Tandy, from the adjacent police post, saw what was happening and went to speak with the three men. After spending 'quite 10 minutes with them', according to Woodward, he cantered back and crossed the spruit at the drift (sworn statement by Acting Corporal E H Woodward [Transvaal Archives, PMO 81, file no 37]). Tandy reported that the Boers had asked to see an officer so as 'to assure them that they would not be compelled against their own countrymen' (sworn statement by Acting Corporal E J Tandy [Transvaal Archive, PMO 81, file no 37]; Wilson, After Pretoria, pp798-800). Shortly thereafter, Tandy and Woodward met Captain Miers, who had his dog with him, on his grey mare. Tandy told Miers what the Boers had said. Miers reproved both corporals for having acted wrongly and foolishly. He wrote a note for Captain Capell and left his carbine and bandolier, but not his revolver, in Woodward's fort and crossed the spruit towards the Boers (sworn statement by Acting Corporal E H Woodward [Transvaal Archive, PMO 81, file no 37]).

The British soldiers, watching from their small forts, saw one of the Boers with a white flag come forward to meet Captain Miers. After a short conversation with the man, Captain Miers went with him to the other two Boers. Shortly afterwards, the soldiers in the forts heard a faint shot and saw the Captain's mare galloping away. It later turned out that the three Boers who were involved in the incident were Salmon van As, Louis Slabbert, a young man who spoke no English, and Piet du Toit, 'a thirty-year-old man (a whole lot older than I)'. Slabbert had been told by van As to put his rifle down 'and stop that fellow so that he does not get into our outpost'. Slabbert was two hundred yards (183 metres) away from the Boer outpost when he shouted at Miers to stop. Miers ignored him and galloped up to van As. Slabbert followed on foot and was 'ten yards (9 metres) behind the Englishman's horse' when a shot rang out. All Slabbert could say was, 'God, Veldcornet, why did you shoot that man?' (according to war memories of Louis Slabbert as told to his daughter in 1953), but he always maintained that he had not seen what had happened. Piet du Toit would have had an even better view of the incident from his position. After the shooting, the three Boers made their way back to the farm, De Kuilen, where van As reported to a senior officer. Van As had taken Miers' revolver and binoculars and these were seen by a number of their commando colleagues. Van As always maintained that his deed was an act of war and that he had acted in self-defence.

Had van As acted in self-defence after being threatened by Miers with his revolver? We will never know. The British corporals were adamant in their sworn statements, made within a day of the shooting, that Corporal Tandy had been lured out by the Boers, who were waving a white flag, which was a recognized signal of truce. Captain Miers had stated, in his note to his senior officer, that he would go out cautiously in the direction of the Boers and see if the one with the white flag would come to meet him, but he would not use a white flag. In Louis Siabbert's account to his daughter, written more than 50 years after the incident, however, he stated that Captain Miers had indeed approached them with a white flag. It is also conceivable that van As had been ordered to deal with Miers, who was a nuisance to the Boers by seeking to persuade them to lay down their arms (Louis Slabbert makes such a suggestion in the account told to his daughter, quoted by H J Jooste in 'Veldkornet Salmon van As', Christiaan de Wet Annale 6, 1984 ).

Corporal E H Woodward also wrote a letter to The Times (London, 29 November 1901) describing the incident in rather lurid detail. Whether a journalist had helped him with the letter is unknown. The letter is very well written, the facts are as stated in his sworn statements, but the language is emotive, describing how Miers' body was 'stripped of everything but his shirt ... ' Although the Boers denied this, at that stage of the war it would have been difficult to overlook a good pair of boots and Woodward's account is not inconceivable (sworn statement by Acting Corporal E H Woodward [Transvaal Archives, PMO 81, file no 37]). Shortly after the appearance of this letter, an account appeared in H W Wilson's After Pretoria, based very much on Woodward's letter. (The publication, After Pretoria appeared weekly and was only later bound into a large volume which appeared in May 1903). These accounts of the incident created a good deal of interest in Britain, the matter being raised by the opposition in Parliament.

The SAC investigated the incident and regarded it as an act of murder. The matter was reported to Kitchener, who thereafter addressed a letter to General Louis Botha, the last sentence of which was unequivocal: 'I trust your honour will see that the murderers are brought to justice.' (Letter from Kitchener to Botha in the Transvaal Archives, PMO 81, File 37). Botha referred the matter to General Piet Viljoen on 28 November 1901 who replied that 'he knew nothing at all of the alleged murder and no such incident has been reported by my officers.' (Reply of General P R Viljoen to Botha's letter of 28 November in the Transvaal Archive, Preller collection, Volume 34, document 693.) Commandant Alberts was also asked to investigate, but became convinced that van As was innocent of any charge and that he had acted on the orders of his superior officer and in self-defence (G S Preller, Sketse en Opstelle, p 163.)

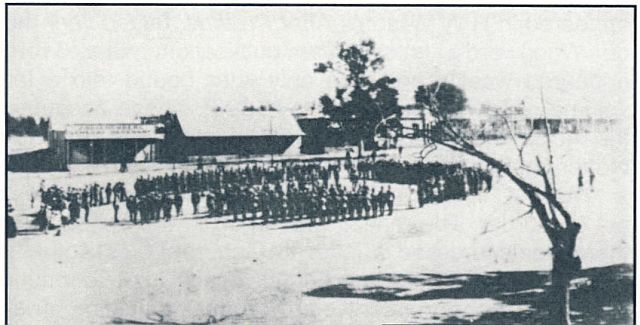

Assistant Field Cornet Salmon van As was with the Heidelberg Commando at Kraal Station, south of the town, when they laid down their arms on 2 June 1902. General Louis Botha told them about the terms of peace and that they were to surrender their arms while the officers could retain theirs. He told them that van As was excluded from the amnesty provided in the peace treaty. Van As asked the general if his life was guaranteed, but Botha told him that 'nothing will be done to you. There will only be an investigation' (Uys, 1981, p227).

Van As then approached Major-General Bruce Hamilton at Kraal Station and 'surrendered voluntarily' according to Hamilton's letter of 7 June to Lord Kitchener (Transvaal Archives, PMO 81, file no 37). By 8 June, both van As and Louis Slabbert had been arrested and were being held in the Heidelberg army camp. Piet du Toit's name was called when the other two were arrested but he was not found. Du Toit, who was thought to be a prisoner-of-war in Bermuda or India, had in fact been held in Merebank Camp in Durban. He arrived back in Heidelberg on 5 June 1902, passing the surrendered burghers at Kraal Station. He was not immediately arrested, but there is a letter in the Transvaal Archives to the effect that his trial was to take place at Pretoria. However, there is no further record that any trial ever took place.

The court martial

The court martial of van As and Slabbert took place in the Waverley Hotel on 17 to 19 June. The record of the proceedings has never been traced. The British produced, as evidence, sworn statements from three black men and six black women from the farm, De Kuilen, and, also as witnesses, Major Phillips, Corporals Woodward and Tandy, and Trooper Wallis, all of the SAC. The black witnesses all mentioned seeing a revolver and binoculars in the possession of van As and also boots, gaiters and other items of clothing. (The various sworn statements are in the Transvaal Archives, PMO 81, file no 37). Van As was apparently fluent in English, as he had grown up in Heidelberg, which had a substantial English population at the time. He apparently cross-examined the black witnesses and destroyed their credibility as they could not have seen what had actually happened. Slabbert did not understand much of the proceedings because of his lack of English, but he clearly understood van As's cross-examination of the black witnesses, as that was conducted in Afrikaans. Nevertheless van As was convicted of the murder of Captain Miers and sentenced to death. The court martial must have based its findings substantially on the evidence of the two corporals, and in particular on the evidence that the Boers had waved a white flag before Captain Miers rode out towards them. Louis Slabbert was sentenced to penal servitude for life, which was later varied to five years. Slabbert was released after an amnesty was given to all political prisoners and Cape and Natal Colony rebels. He eventually served twenty-one months of his sentence. (See Jooste, 1984, pp63-65 for Slabbert's account of the court martial proceedings.)

Execution

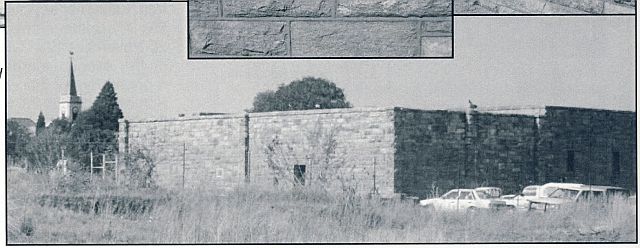

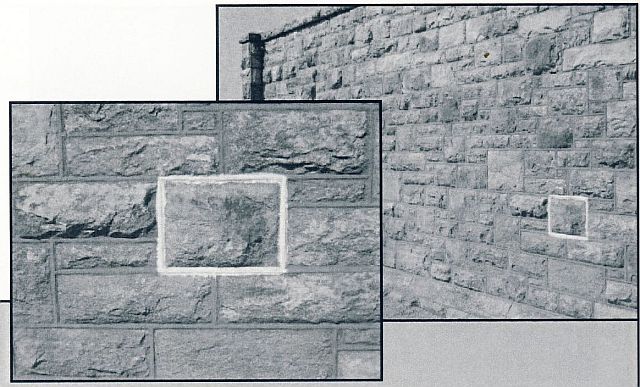

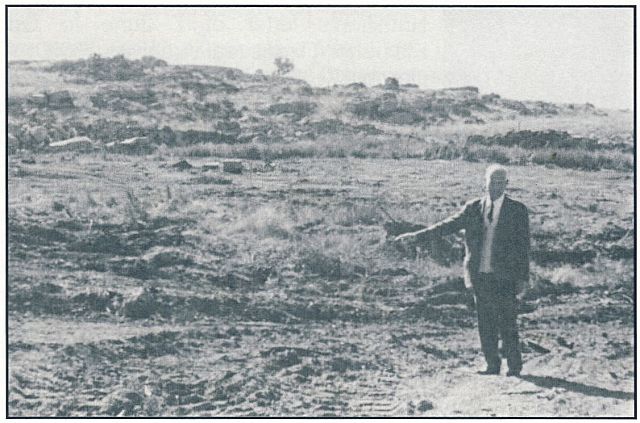

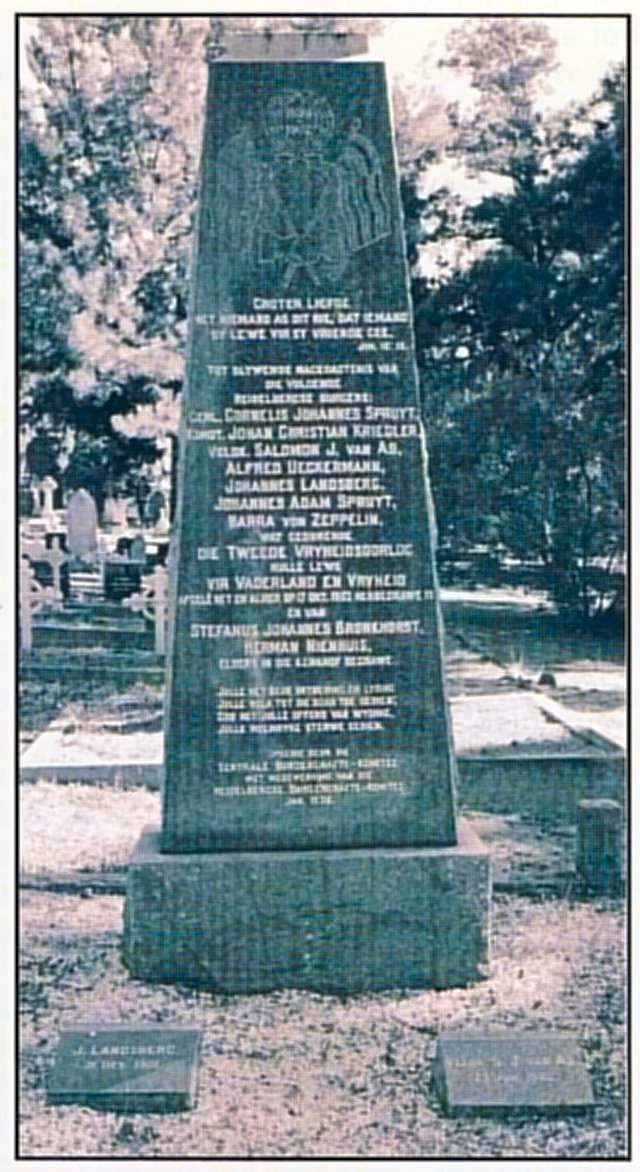

Salmon van As always maintained that he was innocent of murder but did not deny that he shot 'one of the enemy's captains who aimed his revolver at me'. Generals Piet Viljoen and Hendrik Alberts tried very hard to get in touch with General Botha in connection with the court martial, but to no avail. Viljoen visited van As in his cell the day before his execution and van As reaffirmed his innocence. Van As was executed by firing squad on Monday, 23 June 1902, standing up against the stone wall at the back of the Heidelberg jail. His body was wrapped in a blanket and buried near a thorn bush a short distance away. In October 1903, van As, General Spruyt, Commandant Kriegler and six other war casualties were reburied in the Old Heidelberg Cemetery. General Louis Botha did not attend the ceremony, although he was scheduled to be there (Uys, 1981, pp 234-36; Uys, 2002, pp 189-91 ).

In 1904, van As's father allegedly received a letter from the British Government which acknowledged that the trial had not been a fair one. Perjury had been committed (apparently by the black witnesses) and van As had not been able to call his own witnesses. A claim for compensation would be entertained but his father declined to make a claim. He blamed Louis Botha for his son's death and did not allow the mention of Botha's name in his presence (Uys, 1981, p232).

Afrikaners have always regarded Salmon van As as a martyr and a symbol of British injustice. In 1916 the well-known Afrikaans poet, C Louis Leipoldt, composed a poem on van As which has become part of Afrikaner folklore.

Barend Cilliers

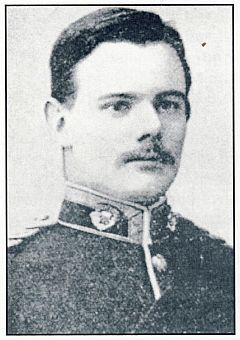

The second man for whom amnesty was denied was Barend Celliers, a burgher of the Orange Free State. When General Christiaan de Wet captured the town of Dewetsdorp on 23 November 1900, a number of British soldiers were taken prisoner. Among these was Lieutenant Cecil Boyle, a member of the newly formed Orange River Colony Police, who was Assistant District Commissioner in the town. According to Mildred Dooner (1903, 1980 reprint, p35), Boyle was ADC in Lindley in the north eastern Orange Free State. Shortly thereafter, Dewetsdorp was evacuated by the Boers when de Wet headed off on what was to become an abortive attempt to invade the Cape Colony (Maurice, Vol 3, pp492-96). Boyle was taken with them. He was accused of ill-treating Boer women by making them walk instead of riding in wagons on their way to the concentration camp, as well as threatening them with a sjambok (a rawhide whip used for herding cattle and for inflicting corporal punishment). Earlier in the year, Boyle had been captured by the Boers and taken to Lesotho, where he had been warned not to take up arms again, because the next time he would be shot. (Lourens, Te na aan ons hart, 2002, has some details of these accusations which appeared in the Die Volksblad in October 1900, with the spelling, 'Cilliers'). The prisoners were required to accompany the Boer expedition, but, hardpressed by the column of Major-General Charles Knox, all of the prisoners, except for Boyle, were released. (Boyle was required to walk 'just like the women and children' according to Die Volksblad, 6 October 1899) .

General Philip Botha, one of de Wet's officers, an older brother of Louis Botha, was ordered to guard Boyle and took part of the commando to the Doornberg, outside Kroonstad and north of Senekal. Field Cornet Celliers was delegated to guard the captive.

On 2 January 1901 the commando was on the farm, Blijdskap, on the Liebenbergsvlei River. It was here that General Philip Botha gave Celliers his instruction that Boyle should be executed. Celliers was ordered to 'take Boyle an hour's ride out of the laager and to shoot and bury him' (Rex versus Celliers, Reports of cases decided in the High Court of the Orange River Colony for 1903, p2). Celliers, accompanied by a burgher by the name of Smalberger, carried out this order. This was done on the farm 'Hartebeeshoek West', 19km south-west of Reitz. Boyle asked to write a last letter. His request was granted and, afterwards, he was shot in the back as he prayed. Boyle's documents were burned, presumably including his last letter. (His family does not appear to have received it).

Celliers made no secret of his action on his return to the laager, clearly giving the impression that he had carried out the orders of a superior officer. (Smallberger had apparently joined Celliers and Boyle when he was out looking for horses, according to Lourens, 2002, p226).

Celliers' commandant, Philip de Vos of the Kroonstad Commando heard what had happened and reported the matter to de Wet and President Steyn, who, on'26 January 1901, called on Celliers to account for his actions. General Philip Botha was killed in action in a small skirmish in the Doornberg on 6 March 1901. (Malan, 1990, p19; Chilvers Vol IV, 1907, p234; and Maurice History of the war in South Africa Vol 4 p93.)

On 26 July 1901, Celliers was tried by a Boer courtmartial at 'Blijdschap', a farm near Reitz where the Orange Free State government was based for a short time. Celliers gave a statement to the court and Smalberger was called as witness. Celliers was acquitted of murder, the court martial finding that Celliers had acted under the orders of General Philip Botha even though none of Botha's staff members were aware that such an order had been given. (Lourens, 2002, p227: Neither De Vos himself, Botha's adjutant, F J van Reenen, or his secretary T F Moll.)

Celliers was wounded in a later action and taken to the British military hospital in Kroonstad. Once he had recovered, he indicated under interrogation that he knew the whereabouts of the place where he had shot and buried Boyle. Together with an escort, he was sent to find the grave. The body was exhumed and reburied in the Kroonstad cemetery after being identified, apparently from his sister's knowledge of a gold filling in one of his teeth.

Celliers was held in custody until he appeared before a jury in the High Court in Bloemfontein on 20 February 1903. The court proceedings were conducted under the Roman-Dutch law of the former Boer Republic even after the British annexation. The Presiding Judge, J Fawkes, was a Scotsman, appointed to the Orange River Colony Bench because Scots law was much closer to Roman-Dutch than English law. At the trial, Celliers pleaded not guilty to the charge of murder. He did not deny having shot and killed Lieutenant Cecil Boyle, but his defence was that he had been acting on the orders of General Philip Botha. He was defended by J B M Hertzog, who had been a judge in the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State. Hertzog at first moved that, as Celliers had already been acquitted by the previous court martial, such acquittal must stand until such time as it was set aside by an appeal to a competent court. Fawkes, however, ruled that the trial must proceed as the Boer court martial had not been a competent court recognized by the Crown (Rex versus Celliers Reports of cases decided in the High Court of the Orange River Colony for 1903 pp1-7.)

At the trial, Christiaan de Wet gave evidence that the former Orange Free State President, Marthinus Steyn, had suspended General Philip Botha when hearing of his action in issuing the offending order to Celliers, who was bound to obey. Smalberger, presumably the only witness to the shooting, had died before the end of the war. In the Judge's directions to the jury, he stated that 'a soldier on active service was justified in obeying the order of his superior officer, provided that order was not manifestly illegal'. He also directed that it was for the prisoner to prove that the order was not manifestly illegal. After deliberation, the jury acquitted Celliers and he was released.

Celliers was in many ways an outstanding burgher and fought throughout the Anglo-Boer War with the Kroonstad Commando. He was wounded five times, and his last wounding unfortunately brought him into the hospital at Hoopstad, where he was captured by the British. After Celliers' acquittal, he lived on his farm 'Stinkhoutboom' near Vredefort. He was a follower of de Wet and was involved in the rebellion of 1914. General C F Beyers and a number of men, including Celliers, were trapped by Union forces against the Vaal River and Beyers was drowned attempting to cross. In 1920 Celliers was elected to the Provincial Council of the Orange Free State and in 1935 he became a senator in the Union parliament. He died in 1947 and is buried on his farm (Malan, 1990, p68).

Josef Muller

Josef Muller, a burgher from the Vrede district, was the third Boer who was required to stand trial for murder after the cessation of hostilities. Five Rademan brothers, from the farm Raaikloof in the Harrismith district, were unwilling from the very outset to defend their fatherland and join the war on the Boer side. One of them, Marthinus, crossed the border into Natal and lived in Newcastle for the duration of the war. The other brothers hid in the mountains so as to avoid commando service. One brother, Johannes Jacobus, was captured by the Boers and held for a while in the jail at Harrismith. He was then sent over the border into Natal, apparently to prevent him giving any assistance to the British. John Frederick Rademan was the subject of a story in the Natal Mercury, 18 February 1901. The story ran under the headline 'The Murder of John Rademan' and told how Rademan had refused to join the burghers on commando on the grounds that he was unwilling to break the oath of neutrality that he had signed. President Steyn had refused to acknowledge the oath and Rademan's attitude enraged his fellow countrymen. The newspaper reported, wrongly, that he had been shot at his farm, Raaikloof, but did not name his adversaries.

It appears that John Rademan had in fact been called up on commando but had deserted and tried to hide at his mother's farm near Memel. In December 1900 a burgher, Josef Muller, was ordered by Field Cornet Charles Meintjies to bring him back, dead or alive. When the burghers went to get him, Rademan refused to leave with them. Allegedly, Rademan went for his rifle and Muller shot him dead. If this was the case, then certainly Muller acted in self-defence. (For more information on Josef Muller see Blake, 2010, pp215-17.)

Another brother, Cornelius Johannes Rademan, claimed after the war that he had never been on commando and escaped military service by claiming that he was medically unfit. After the shooting of his brother John in December 1900 he went over the border into Natal, acted as a guide for a British column and was even paid the considerable sum of £400 for his services.

There is no record of Josef Muller having been tried for the murder of John Rademan.

Bibliography

Blake, Albert, Boereverraaier (Tafelberg, Cape Town, 2010).

Chilvers, Hedley (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol V (Sampson Low, Marston and Co Ltd, London, 1907).

De Villiers, J C (Kay), Healers, Helpers and Hospitals (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2008).

Dooner, Mildred G, The Last Post (J B Hayward & Son, Polstead, Suffolk, 1980 [reprint of edition of 1903]).

Jooste, H J, 'Veldkornet Salmon van As' in Christiaan de Wet Annale 6 (Die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns in samewerking met die Oorlogsmuseum, Bloemfontein, Oktober 1984).

Kestell, The Rev J D, and van Velden, D E, The Peace Negotiations (Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd London, 1912).

Lourens, J and J A J, Te na aan ons hart: Aspekte van die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die Reitz omgewing (Privately published, 2002).

Malan, Jacques, Die Boere-Offisiere van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, 1899-1902 (J P van der Walt, Pretoria, 1990).

Maurice, Major-General Sir Frederick, History of the War in South Africa, Volumes 3&4 (Hurst and Blackett Limited, London, 1908 and 1910 respectively).

Scholtz, David, 'Lieutenant Cecil D Boyle: Summary of the circumstances of the shooting of Lieutenant Cecil D Boyle by Commandant Barend Celliers and the latter's subsequent trial in Bloemfontein' (unpublished document).

Uys, Ian, Heidelbergers of the Boer War (Ian Uys, Heidelberg, 1981).

Uys, Ian, Fight to the Bitter End (Fortress Financial Group [Pty] Ltd, Knysna, 2002).

Wilson, H W, After Pretoria II (London, 1903).

Reports of cases decided in the High Court of the Orange River Colony for 1903.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org