The South African

The South African

Introduction

It is seldom that a newcomer to a field of history has such an immediate and lasting impact as Thomas Pakenham did with his book, The Boer War. He set out, as he told his readers, to write his history of the conflict from first-hand and largely unpublished contemporary accounts. He said in his introduction what a work of detection The Boer War had been: 'I stumbled on the lost archives of Sir Redvers Buller - which had remained hidden under the billiard table at Downes, his house in Devon, and in Lord Lansdowne's muniment room at Bowood - I traced over a hundred unseen sets of letters and diaries, written by British officers and men who served in the war; these were generously lent to me by their descendants.' (Pakenham, 1979, pp393-4). Readers shared in his work of detection by finding, as the book proceeded, how the author wove these sources into a story of unsurpassed interest and "liveliness. Reviewers praised his writing. 'A tour de force narrative,' said John Gooch in the English Historical Review, 'which not only tells the story of the war better than it has ever been told, but along the way forces us to revise some of our judgments on the leading military figures of the day.'

One of Pakenham's achievements was to rescue the reputation of General Sir Redvers Buller, whom Lord Salisbury's cabinet removed from supreme command after the defeats of 'Black Week'. Does Pakenham's brilliantlywritten defence of Buller still hold water? Eugene Terreblanche thought The Boer War as admirable as Shakespeare, but it is not Gospel (Nasson, 1999, p272). One academic reviewer (Greenberg, 1981, p356) wrote that '[w]hile his survey of the sources is impressive, Pakenham is not above creating details when they are unavailable' and perhaps also when these details do not fit his story.

Pakenham knew how to write a best-seller. The 1960s and 1970s were iconoclastic decades, when Britain's allegedly glorious past was under attack and established opinions were overturned. Julian Symons (1963) had not long before reiterated the established truth, that Buller was an incompetent whose campaign was a succession of blunders (see also John Walters, 1970, pp138-62). Pakenham devoted no less than sixteen chapters to Buller's campaign in Natal in 1899 and early 1900, his removal from supreme command, and his replacement by Roberts and Kitchener.

He sets the background by giving an account of the 'rings': Wolseley's 'Africans' and Roberts' 'Indians'. The author writes in his introduction that 'St John Brodrick, who became British War Minister in 1900, later compared the wrangles between Lord Roberts and Sir Redvers Buller to those between Lord Lucan and Lord Cardigan which precipitated the Charge of the Light Brigade'. Brodrick actually wrote: '[When I became Secretary of State for War in November, 1900] there had long been a divergence between the Wolseley reformers who had recently controlled Pall Mall and the brilliant band of Indian soldiers to whom, from the Kabul-Kandahar period twenty years before, Lord Roberts had been an inspiration' (see Pakenham, 1979, xvii and the Earl of Midleton, 1939, p120). In fact, the 'African' ring was by then broken, some members like Brackenbury and Ardagh having become 'Indians', Evelyn Wood and, to an extent, Buller having fallen out with Wolseley, and others dead. By 1899 Wolseley was ill, his memory going. Members of the 'ring' were more likely to owe their loyalty to Buller or Evelyn Wood. (For more on the 'rings', see Beckett, 1992, p20 and Badsey, unpublished PhD thesis, p122).

In any case, does the rivalry of 'Indians' and 'Africans' really account for Roberts' view, expressed in confidential letters to Lansdowne, that Buller was not up to the job? Roberts was present as an observer at the Salisbury Plain manoeuvres of 1898 where, as the historian D M Leeson (2008, pp432-61) tells us, 'Buller was defeated in almost every battle ... just as he was later in the South African summer of 1899-1900'. These Salisbury plain defeats bore more than a passing resemblance to Colenso. Brodrick (Earl of Midleton, 1939, p133) quotes Buller as saying that he had been making 'a fool of [himself] all day'. The future Lady Milner (1951, p110) 'wondered what Lord Roberts thought of it all, but he was far too discreet to say anything critical on this occasion'. Roberts, with his experience of Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier, could clearly see how little the manoeuvres reflected new firepower. The main armies operated in squares and advanced in solid lines. When his protege, Colonel Ian Hamilton, kept his men concealed and sent out mobile groups that overran enemy headquarters, he was admonished for using unorthodox tactics in war games (Hamilton, 1966, pp122-3). But, one might ask, would the Boers behave in orthodox fashion? (Powell, 1994, p 113) notes that Roberts was staying at Aldershot as Brodrick's guest.

Pakenham's account of 'the rings' seeks to explain the antipathy to Buller leading to his removal. What he ignores was the cabinet's lack of confidence in him. Comments from Lord Salisbury are apposite. When Violet Cecil said that Buller looked like a strong man, he answered, 'Do you think that a pig has any fixity of purpose?' When family conversation got round to the execution of Admiral Byng in the Seven Years' War, Salisbury said he wished Buller had lived in those days. Pakenham attributes hostility to Lord Lansdowne, Secretary of State for War and Lord Roberts' friend, but the speed of Buller's supersession showed the cabinet's overall misgivings about his ability (Roberts, 1999, pp791 ,822).

The defence of Buller

Pakenham claims justice for Buller against what he calls 'Amery' but really means The Times History of the War in South Africa. This multi-volume account had, as editor-in-chief, Leo Amery, Balliol scholar, fellow of All Souls, Times correspondent and aspiring army reformer, but it was really a team effort by reporters assisted by young officers. The latter came from the 'Roberts' kindergarten' as the Canadian historian Nicholas d'Ombrain described them, men intent on overhauling the War Office and an Army which they regarded as 'a gigantic Dotheboys' Hall' (Times History, Volume II, p33). To them, Roberts represented reform and Buller, erstwhile Quartermaster-General and long-time Adjutant-General, personified muddle, with ten years at the War Office and so little to show for it. (Actually, Buller was fifteen years and six months at the War Office, but only ten in posts of senior responsibility). Amery wrote much of the first three volumes of the Times History, with Lionel James and others helping, and he wrote half of the sixth; the fourth and fifth were chiefly by Basil Williams and Erskine Childers respectively. Volume II, which appeared in May 1902, created a tremendous sensation by its outspokenness, notably its criticism of Buller. 'Bron' Herbert, Buller's cousin, wrote the account of Buller's campaign in volumes II and III. He was unlikely to have accepted Amery's views uncritically. While working on the battle of Spion Kop, he wrote to Amery,

'I am become rather late in the day nearly as ardent an anti-Bullerite as yourself.' (Amery, 1953, Volume I, pp 152-7, 158, 160 and introductions to different volumes of the Times History; Amery papers, AM EL 1 /1 /11, 14 September [1902]).

Pakenham (1979, pxvi) speaks cavalierly of the Times History and its official War Office rival, largely written by Frederick Maurice: 'The Times History says too much ... always partisan ... The Official History says too little ... Few sources from the Boer side of the hill, official or private, were available to their author.' The last is true, but Amery did his best, for example taking a Boer account of Spion Kop from British Intelligence in South Africa. In the preface to Volume II, he even thanked 'those friends of mine who have taken part in the war as burghers of the Boer Republics, by whose help I have been enabled to give some account, however inadequate, of that little known side of the operations.' (Amery papers, AMEL 1/1/18, 29 April; also Times History, Vol II, preface, ix).

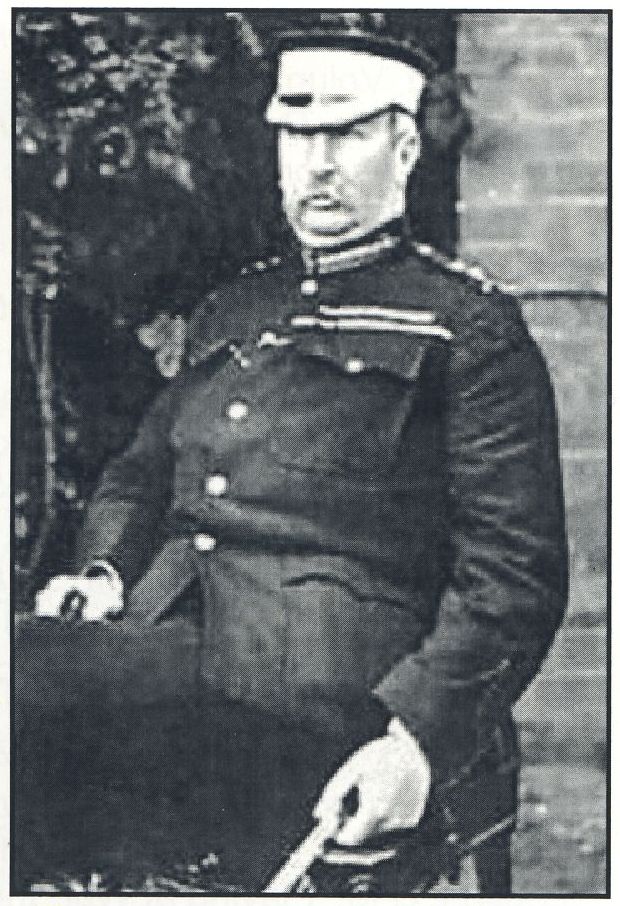

Buller was not the bluff, good-hearted country squire of Pakenham's brilliant pen sketch, but a man with deep-seated uncertainties. When he was sixteen, he witnessed the sudden collapse of his mother on a railway platform. She had suffered a massive haemorrhage and died in his arms three days later. It was just before Christmas, a time for families. His biographer, Colonel Melville, commented: 'Such a blow, coming at such a season and under such painful circumstances could not but affect a lad deeply.' Six months later he suffered another loss in the death of his elder sister, to whom he was much attached. His school career was undistinguished. As Melville discreetly writes, he left the family school, Harrow, 'on account of some difference of opinion with the authorities'. Virtually the only thing he remembered from his Eton days was kicking another boy called Dunsmore at football. Known in his youth for uncontrollable rages, he channelled his aggression in the army, but the scars on his psyche remained.

In the 'Ashanti ring' Buller was noted for deeds of physical strength and courage, excellent in a subordinate role, but indecisive when given lone command. He was partial to rich food and magnums of Veuve-Clicquot. A trail of camels carried his goodies from Fortnum & Mason's through the Sudanese desert. He was jealous of other members of the ring with more confidence. Wolseley wrote, '[Sir Herbert] Stewart [is] much the better man of the two all round though Buller has some excellent military qualities. Buller never loses a chance of crabbing Stewart's ability and making out that he [is] constantly wrong.' In the War Office from 1887, he grew fat and in 1899 told everyone who would listen that he was not up to commanding the army corps in South Africa. It would have been better, as General Neville Lyttelton later wrote, if they had heeded his dire misgivings (Col Melville, 1923, p18; but see also Symons, p293; Asher, 2006, pp1 06,185; Preston, 1967, introduction; and Lyttelton, pp100-1).

Buller in South Africa

Buller reached Cape Town on 31 October to find British garrisons besieged. 'It was not Buller who showed weakness and despondency', Pakenham tells us, 'Buller was the man who breathed life into the quaking garrison at Cape Town.' At Cape Town? Quaking garrison? Weren't the Boers over 400 miles (640km) away on the Modder, or stuck in sieges? Soon after his arrival, Buller wrote to his brother: 'I am in the tightest place I have ever been in ... ' (National Archives: W0132/6/841 3 November 1899). This from a man who had won the Victoria Cross against the Zulu and who had stared Dervishes in the face at Tamai as they broke into a British square? Was he not showing despondency? Pakenham thinks that somehow this letter reflects credit on Buller, who commanded, in South Africa, the biggest army Britain had sent abroad and whose next decision was to break it up. What about concentration of force as a principle of war? We are told that he performed prodigies. He did organise medical provision, including Gandhi's 'body-snatchers' (stretcher bearers) and canteens so excellent that his army crawled rather than marched on its stomach. Pakenham next tells us, 'Then came disaster, Rhodes stranded at Kimberley, White at Ladysmith. Buller had to drop everything and speed away .. .' (Pakenham, 1979, pp 158,160-5; but also see Symons, pp139-41). Is this what a commander-in-chief should do, ie. let the Boers dictate strategy? Neither Ladysmith nor Kimberley was about to surrender. At the end of the next chapter, we read that 'the Boers had shot their bolt'. If so, why did Buller have to 'speed away'? Even Bron Herbert in the Times History (Volume II, p286) sympathises with his decision, but, had Buller stuck with the original plan, he would not have faced such a difficult task along the Tugela.

Pakenham (1979, p231) tells us that Buller's defeat at Colenso was due to blunders by General Hart commanding the Irish Brigade and Colonel Long commanding the artillery. In fact, as Darrell Hall has shown, Long operated according to the 1896 artillery manual, had achieved fire superiority and, although wounded, requested resupply. He was countermanded by Buller, 'a decision which more than anything else,' says Hall, 'was to spell disaster for the gunners.' Most of the guns were lost, thanks to Buller, not Long. Lord Roberts' son died in an unnecessary 'rescue' attempt (Hall, 1991. John Hussey, reviewing in the Journal for the Society of Army Historical Research, Vol 73, 1995, pp285-6, called Hall's analysis the most searching; Pakenham's account is completely at odds with Herbert's account in the Headlam papers at Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institute). Pakenham neglects Botha's view, published in several places, that Buller's force was saved from disaster by the actions of Long and Hart, who frustrated his intention to drawn the Rooineks into a carefully prepared trap: 'when Colonel Long rushed his field artillery out, he upset the whole plan ... it was Colonel Long who saw [our men],and realized that. .. there was grave danger of a flank attack, and he made it so hot that they had to open fire all along and so gave the whole plan away ... that man saved the British army that day.' (Headlam, Royal Artillery, III, p 383, quoting Sir J Percy Fitzpatrick, South African Memories; Maurice, Vol 1, p 374.

Ladysmith

Using Pen Portraits of the War, a propagandistic source, the author describes Buller behaving bravely: 'Buller, VC, the dare-devil of the Egyptian and Zulu wars' was back in action. After his defeat he is enraged by a cable he received the day before from Lansdowne 'telling him to sack Gatacre and Methuen'. Was this telegram really more important than exhausting hours spent in the saddle, the heat, the effects of defeat, a wound from a spent round, the loss of men and officers including Roberts' son? What about those despairing signals Buller sent to White in Ladysmith and to London, which Pakenham glosses over? 'A serious question is raised by my failure today, I do not now consider that I am strong enough to relieve Ladysmith ... I consider I ought to let Ladysmith go and to occupy a good position for the defence of South Natal. .. But I feel I ought to consult you on such a step.' (Pakenham, p 235; The National Archives, W0108/399, pp 52-3, Nos 53d and 54, 15 December 1899 and No 66).

The horrified Lansdowne replied, 'The abandonment of White's force and its consequent surrender is regarded by the Government as a national disaster of the greatest magnitude. We would urge you to devise another attempt.' Buller's old uncertainty, causing him to seek someone to relieve him of supreme responsibility, had re-asserted itself, but, on receiving Lansdowne's answer, he breathed a mighty sigh of relief by telegram to the secretary of state: 'Much obliged for your No 53. Exactly what I wanted.' (The National Archives, W0108/399, p 55, No 57 and p 59, No 66, 16 December 1899. The second includes a strange reference to 'financial considerations at Ladysmith'.)

Not just the besieged in Ladysmith, but the Queen and the government believed Buller had called on White to surrender. This finished him as C-in-C in South Africa in the eyes of Salisbury, Balfour and Lansdowne. The Queen herself wrote in her journal after seeing Buller's message: 'Talked for a long time to Sir A Bigge about this telegram, and desired him to cipher to Lord Lansdowne that I thought it was quite impossible to abandon Ladysmith.' (Buckle, Vol III, 1922, P 435).

'If only Buller could have expressed himself more plainly, and less bluntly', Pakenham tells us. It is unlikely, in fact, that Buller knew what he was doing, otherwise why would he send a confused, defeatist message asking advice from the Secretary of State, whom he despised? Everything suggests that he was totally overwhelmed by the problems before him. To sustain this picture, Pakenham ignores so much. In January, 1900, Buller telegraphed Lansdowne to say he was facing 120 000 Boers and foreign mercenaries. The astonished Lansdowne replied that the entire Boer male population of the Transvaal was not that large.

Pakenham cleverly slips into a later chapter a mention of Buller's hare-brained scheme for building a railway towards Bloemfontein and following it with the army. (Pakenham, pp 239, 381; The National Archives, W0108/399, P 78, No 94, 9 January 1900; National Army Museum, Roberts papers 7101-23-181, 10 January 1900; Maurice, Vol I, 1906, pp 410,413). Maurice tried to keep a straight face, but admitted that hopes of the railway being built in a month were 'too sanguine' even if one ignored the need for guards. Pakenham blames Buller's next defeat, Spion Kop, the costliest of the war for the British, on his subordinate, Sir Charles Warren. What strange impulse led him to entrust the larger part of his army to this irascible man with whom he was on the worst terms personally? For explanation, Pakenham falls back on Buller's testimony after the war (Pakenham, pp 282-3 and endnote 49 on p 619, 'Lewis Butler-John Fortescue, quoting Buller' after the war. Fortescue, Buller's fellow Devonian, was also his defender).

Of Buller's defeat at Vaal Krantz, where the British suffered 333 casualties, there are a few cursory lines. As Edward Spiers pointed out, this was an attack executed and lost by Buller, not by Long, Hart or Warren. Pakenham went on to claim that Buller proved among British generals to be the 'innovator in countering Boer tactics': he writes, 'for the first time Colonel Parson's gunners could fully exploit Buller's revolutionary new tactic for co-ordinating artillery and infantry'. In fact, as Howard Bailes has shown, revolutionary infantry tactics had been pioneered on the North-West Frontier of India, and brought to South Africa by Ian Hamilton, who used them at Elandslaagte' (Pakenham, pp 307, 314, 320,344,361; Spiers, 1992, p 314; Bailes, 1980, pp 73-4, 76,83-4).

Edward Spiers tells how, before the war, Buller had pooh-poohed lectures at which junior and middle-ranking officers warned about the effect of smokeless, long-range, magazine rifles. 'There is nothing new under the sun,' he said 'and when improvements are made in military arms and tactics they almost always follow along the same lines.' Nor was his vision widened by his experiences in South Africa, claiming to the post-war Royal Commission that pre-war standards of drill and training were perfectly adequate. 'I saw nothing [in the war] to make me think our drill book was wrong,' he said (Spiers, 1981, pp 82-4).

Pakenham's argument, however, that the Natal army pioneered 'creeping barrages' does hold water. The papers of Buller's chief artillery officer, Colonel Lawrence Parsons, now at Woolwich Arsenal, support Pakenham's insight. On 27 February, Parsons recorded how he summoned all his battery commanders for orders for that day's objectives and gave each battery its targets. 'Impressed on them all the importance of maintaining fire on point of attack until last moment and when no longer safe to continue on object, to increase elevation 500 yards and fire over own Infantry's heads and possibly into enemy retreating down reverse slope.' Kitchener's brother, Brigadier Walter Kitchener, made his dispositions most carefully. 'He [Walter Kitchener] even told the men that they were to expect to see their own shells bursting just in front of them all the way & that they were not to mind that, nor even an odd shelling bursting among them, as the closer their own artillery fire supported them, the less they had to fear from the enemy's rifles. When his attack once started it simply boomed along ... .' If we give credit to Pakenham for spotting this, it should be added that so did his bête noir, the Times History. Bron Herbert wrote, 'Then [at Alleman's Nek in June] it was that Buller completed the perfect co-operation between artillery and infantry, which was the most noteworthy feature of this battle.' But one wonders why the Royal Artillery then forgot this tactic until the battle of the Somme (Royal Artillery Historical Trust Collection at the RA Museum, Woolwich: papers of Lt Gen Sir Lawrence Parsons, MD111/1 and MD111/3, diary entry 27 Feb, 1900 and letter to wife 16 Jan, 1900; Times History, Vol IV, p192. Even Robert H Scales, in his very thorough thesis, 'Artillery in Small Wars: the Evolution of British Artillery doctrine, 1860-1914' [Duke University PhD dissertation, 1976], does not bring out the full significance of Parsons' tactics, although, needless to say, he does not think of Buller as an artillery innovator). Buller remained inactive for two months after the relief of Ladysmith.

Buller and Roberts

Few commanders had 'so wantonly thrown away so great an opportunity', in the opinion of Brigadier Neville Lyttelton. The young Boer, Denys Reitz, thought his failure to pursue lengthened the war by two years (Lyttelton, Eighty Years, pp 229-30; Reitz, 1948, pp 91-3).

Citing Buller's testimony to the Commission, Pakenham claims Roberts deliberately prevented Buller from advancing, but the evidence proves the opposite. Roberts wanted help as his army marched toward Pretoria, and continually telegraphed Buller in May and early June 1900 to assist. Buller began by giving news of his advance, and then reverted to endless excuses about enemy strength, lines of communications being threatened, and 'I am in rather a tight place'. At last, on 4 June, Buller told Roberts he could assist by forcing Laing's Nek by a turning movement. Roberts' exasperated reply was not to bother; he was already at Pretoria. Major Sir Henry Rawlinson, on Roberts' headquarters staff, wrote in his diary: 'Buller in Natal is still obstinate. I hear that he gives out that Bobs will not allow him to advance whereas we have been doing all we can to get him to make a move. He is so full of excuses .. .' (Bobs 7101-23-118, ops telegrams between Field Marshal Lord Roberts and General Sir R Buller, National Army Museum; see also Rawlinson papers, 5201-33-7-3,13 May, 1900).

Buller gave Roberts no assistance during the march to the Transvaal capital, but his successes at Laing's Nek, the 'Gibraltar' of Natal, at Bergendal, and with Hamilton at Paardeplaats rounded out his campaign successfully. Quoting from his boastful letters to his wife, Pakenham makes the most of this. It is worth a comparison. At the two major British victories of the war, Paardeberg and Brandwater Basin, Roberts and Hunter respectively captured forces of over 4000 Boers. At Bergendal, 'a crushing victory' for Buller, the author tots up Boer casualties: fourteen dead and nineteen prisoners, with some wounded removed (Pakenham, pp 455-6; Breytenbach, Volume VI, p 343. Professor Andre Wessels of Bloemfontein University kindly provided these figures).

In the testimony before the Elgin Commission, Buller made a poor showing, according to Lord Esher, being unable to explain convincingly what he meant by his signals to White (Churchill College, Cambridge, Esher papers, ESHR 15/1, pp 66-70). This testimony, however, Pakenham uses to make his most extraordinary claim: 'Significantly, it was Buller. .. who accurately predicted the peculiar difficulty of a war against [the Boers] ... He predicted the set-piece war would turn into a fragmentary war. .. He compared the present task with the one set Generals Howe, Clinton and Cornwallis in the American War of Independence. It was no good capturing capitals ... .' Surely Pakenham is too good an historian to believe this 'prediction' two years after the event, for his research would have found it in earlier letters if such existed? Geoffrey Powell, Buller's biographer, a more honest if less inspired writer than Pakenham, tells us that in July, 1900 in a 'long and interesting talk with Kitchener' Buller thought the war would be over in 'nine weeks from 1 July', hardly a prediction of a two year guerrilla war! Powell also tells us that the historian of the British Army, Sir John Fortescue, Buller's fellow Devonian, helped him prepare his testimony for the Elgin Commission. Fortescue had just been working on Volume III of his famous history covering the American War of Independence (Pakenham, p 378; Powell, pp 186, 200).

In conclusion

Historical justice required that Buller receive some vindication. White's remaining at Ladysmith placed him in a difficult position. Along the Tugela he faced a hard task: the terrain favoured defence, the Boers had mobile artillery and Louis Botha was a redoubtable opponent. Buller maintained his hold on the affection of his soldiers, and his tactics did improve. His later success impressed his contemporary defenders, the journalist Charles Williams, the French military critic General Langlois, and the anonymous author of The Burden of Proof; or England's Debt to Sir Redvers Buller.

However, Pakenham's defence cannot be taken at face value. His ambiguous use of sources is illustrated in his quoting a sentence of Winston Churchill's. 'A great deal is incomprehensible, but it may be safely said that if Sir Redvers cannot relieve Ladysmith with his present force we do not know of any other officer in the British service who would be likely to succeed' (Churchill, 1900, p 366). These guarded words appear in London to Ladysmith, written for a patriotic British public in the midst of the war. They come two pages after Churchill's suggestion that the quality of the British infantry was so good that if launched altogether into the attack nothing would withstand them (Churchill, 1900, p 364). Buller's failure to do so must be contained within the 'great deal [that] is incomprehensible'.

Privately, to his inamorata Pamela Plowden, Churchill wrote: 'Alas dearest we are again in retreat. Buller started out full of determination to do or die but his courage soon ebbed and we stood still and watched while one poor wretched brigade was pounded and hammered and we were not allowed to help them. I cannot begin to criticise - for I should never stop. If there were anyone to take Buller's place I would cut and slash - but there is no well known general who is as big a man as he is and faute de mieux we must back him for all he is worth - which at this moment is very little.' Buller's pre-war reputation as 'a big man' was still strong, but so poor had his generalship been that Churchill thought Ladysmith would fall (Randolph Churchill, 1967, p 1144). Understandably, Pakenham does not quote this.

Bibliography

Archival sources are indicated in the text.

Amery, Leo, My Political Life (3 volumes, London, 1953).

Amery, Leo (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volumes I, II, III.

Asher, M, Khartoum (London, 2006).

Atwood, R A S, 'How the Royal Navy saved Sir Redvers Buller in South Africa' in Constantine, R J (ed), New Perspectives on the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902 (Bloemfontein, the War Museum of the Boer Republics, 2013).

Badsey, S, 'Fire and the Sword: the British Army and the Arme Blanche Controversy 1871-1921' (unpubl PhD thesis, Cambridge). Dr Badsey's revised work is now published by Ashgate.

Bailes, H, 'Military Aspects of the War,' in Warwick, P (ed), The South African War: the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 (Harlow, Essex, 1980).

Beckett, I F W, 'Wolseley and the Ring' in Soldiers of the Queen: Journal of the Victorian Military Society, 69 (June, 1992), p 20.

Breytenbach, J H, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, Volume VI.

Buckle, G E, The Letters of Queen Victoria, Third Series. A Selection from Her Majesty's correspondence and Journal between the Years 1886 and 1901 (three volumes, London, 1920-2).

Churchill, W S, From London to Ladysmith via Pretoria (London, 1900).

Churchill, Randolph, Winston Churchill, Volume I: Companion Volume Part 2: 1896-1900 (London, 1967).

Greenberg, Allan J, in Victorian Studies, Vol 24, No 3 (Spring, 1981).

Hall, D, Halt! Action Front! With Colonel Long at Colenso (Glenashly, South Africa, 1991).

Hamilton, I, The Happy Warrior: a Life of General Sir Ian Hamilton (London, 1966).

Headlam, Maj-Gen Sir J, Royal Artillery, Volume III.

Hussey, John, review in the Journal for the Society of Army Historical Research, Vol 73 (1995), pp 285-6.

Leeson, D M, 'Playing at War: the British Military Manoeuvres of 1898' in War in History, Vol 15, No 4 (2008), pp 432-61.

Lyttleton, N, Eighty Years Soldiering, Politics, Games (London, nd).

Maurice, Sir Frederick, History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902 (four volumes, 1906-1910).

Melville, Col C H, Life of Buller (two volumes, London, 1923).

Midleton, the Earl of, Records & Reactions, 1856-1939 (London, 1939).

Milner, Viscountess, My Picture Gallery, 1886-1901 (London, 1951).

Nasson, Bill, The South African War (1st ed, London, 1999).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War (London, 1979).

Powell, Geoffrey, Buller: A Scapegoat? A Life of General Sir Redvers Buller, 1839-1908 (London, 1994).

Preston, A, In Relief of Gordon (London, 1967).

Reitz, D, Commando: a Boer Journal of the Boer War (London, 1948).

Roberts, A, Salisbury: Victorian Titan (London, 1999).

Scales, Robert H, 'Artillery in Small Wars: the Evolution of British Artillery doctrine, 1860-1914' (Duke University PhD dissertation, 1976).

Spiers, E, 'Reforming the Infantry of the Line, 1900-1914' in JSAHR, Vol 59 (1981).

Spiers, E, The Late Victorian Army 1868-1902 (Manchester, 1992).

Symons, Julian, Buller's Campaign (London, 1963, republished 2001).

Walters, John, Aldershot Review (London, 1970).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org