The South African

The South African

(This article was also published on www.archivalplatform.org)

Introduction

British interest in lighter-than-air commercial airships or dirigibles was revived in 1924, following the First World War (Crewe, 2009, pp 28-31; http://www.rmets.rmets.org/sites/default/files/histO8.pdt, accessed on 1 November 2013). This was notwithstanding a setback involving the crash of the R38 in August 1921, which resulted in the deaths of many airship experts. The Labour Government issued proposals in 1924 for the construction of two large airships, the R100 and the R101. The Air Ministry decided to develop a national policy for air travel including, amongst other things, the creation of a Royal Airship Works. Detailed climatological data was obviously of major importance for any proposed airship route, and was also essential to select intermediate and main landing bases. There was likewise a need to forecast the weather over long distances and to provide in-flight weather information.

Airship routes

An Airship Division within the Meteorological Office became operational in January 1925, inter alia to investigate the weather on airship routes and elsewhere in the world. An on-site investigation of possible routes and bases was carried out by the Airship Mission over a period of seven months in 1927 (The British Airship Mission, 1927', pp 1057). A plan and map was drawn up in 1929 involving routes between the United Kingdom, Canada, South Africa, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Australia and New Zealand (Crewe, 2009, pp 28-31.

See http://www.rmets.org/sites/default/files/hist08.pdf, accessed on 1 November 2013). The purpose of the Imperial Airship Scheme was to transport passengers, mail and urgent freight as a commercial enterprise, and also to improve links and communication with the mother country (refer here to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Airship_Scheme, accessed on 7 November 2013).

The Zeppelin L59 had been lengthened and provided with additional gas capacity for the African mission. This airship was used in an abortive attempt to supply war material, food and other equipment to the forces of General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck in German East Afnca. Also on board was a medical team to provide assistance to the troops. The airship, after a flight from Friedrichshafen, landed at the airship base at Jamboli (now Yambol) in Bulgaria on 4 November 1917.

The L59 left for Africa on 21 November, but was recalled on 23 November while over the Sudan. The reason was that von Lettow-Vorbeck had sent a radio message advising that he had been forced out of the planned flatlands landing site, and had retreated to very mountainous terrain which was completely unsuitable for use by the airship. It was very probable that the airship would be destroyed, or fall into the hands of the British. The airship, in any event, with its volunteer crew, was not expected to return from her mission, there being no source of hydrogen to replace that vented en route. The airship nevertheless reached her base at Jamboli, and was later used for other duties. She unexpectedly caught fire in the evening of 7 April 1918 in the Straits of Otranto, within sight of a surfaced German submarine. There were no survivors ....

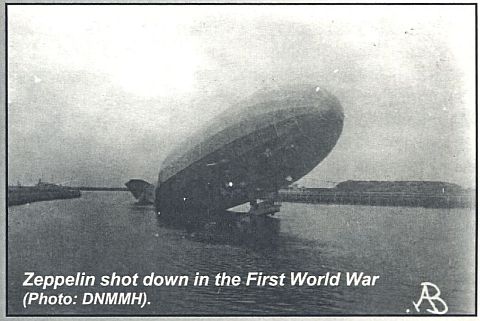

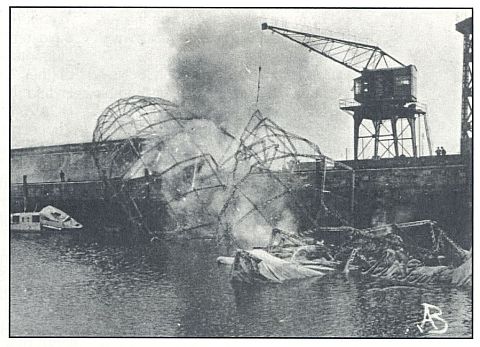

The full story of L59 is available on Wikipedia (http://en . wiki pedia .0rg/wiki/Zeppelin_LZ 104, accessed on 1 November 2013) and in the book by Treusch von Buttlar Brandenfels (1931, pp 169-77). For a personal account of airship missions in the United Kingdom during the First World War, see von Buttlar Brandenfels (1931, pp 232f). The German Navy had a total of 78 airships on the active list in the First World War (p 218). The fleet consisted ot 65 Zeppelins, nine Schütte-Lanz airship's, three Parseval airships and one 'M' airship. Six of the airships were training or special ships which were never used for hostilities. During the war the German Navy lost 52 airships in total (26 airships due to enemy action, fourteen through bad weather conditions and twelve as a result of fire, explosions and other causes, half to enemy action and half to other causes). Of the 52 airships lost, 28 crashed with no survivors. With an additional 17 airships removed from the active list as obsolete, the German Navy ended the war with only nine still in commission on Armistice Day (11 November 1918).

The African Continent

Two African routes were envisaged: one down the west coast, culminating at Cape Town, and the other an east coast route ending at Durban. Africa was virgin territory for airships, since only one flight (apparently) had ever been undertaken in the African interior. This was the German Navy's Zeppelin, LZ 104, designated the L59 and named Das Afrika-Schiff [the Africa Ship]. It was used on the continent during the First World War, although it only reached the Sudan before being recalled to Europe.

A fleet of airships was planned for the Imperial Airship Scheme. The fleet would consist of the R100 (built by the Airship Guarantee Company), the R101 (build by the Royal Airship Works) and the still-to-be constructed R102, R103 and R104. The R100 and R101 soon became known as the 'Capitalist' airship and the 'Socialist' airship respectively.

Possible airship bases along the east coast of Africa were assessed at Mombasa, Dar-es-Salaam, Zanzibar and Durban, and at Mauritius. A series of meteorological reports was issued from 1927 onwards by the Airship Meteorological Division in London. These included: Mombasa (No 24), Dar-es-Salaam (No 25), Zanzibar (No 26), Durban (No 27) and Mauritius (No 30) on the east coast of Africa, as well as Bathurst (Banjul) (No 22), Freetown (No 23), St Helena (No 29) and Cape Town (No 28) on the west coast. Other localities were Malta (No 18), Diego Garcia (No 43), Aden (No 48), Ismaïlia (No 49) and Kamaran Island in the Red Sea (No 70). These can be accessed through the National Meteorological Library and Archive Online Catalogue website by clicking the Online Catalogue and inserting the word 'Airships'.

Further pertinent material is listed on the website, such as a report on the monthly and annual frequencies of thunderstorms across the globe. Over 80 meteorological reports were apparently issued in respect of the planned scheme. It is hard to escape the impression that the route planners were somewhat optimistic, given the state of meteorology in the late 1920s and the lack of long-term weather data in many parts of the world.

Bases investigated on the African west coast were at Bathurst (now Banjul), Freetown, St Helena and Cape Town. There was an existing airship base with a masthead .(mooring mast) at Ismaïlia in Egypt. Factors taken into account clearly included meteorological parameters such as prevailing winds, temperature, humidity, rainfall, the occurrence of fog and especially the incidence of thunderstorms and lightning (both of which constituted a major danger for airships in terms of buffeting in violent winds, and a fire hazard).

Considerable attention was paid to the frequency of thunderstorms along the proposed airship routes. Bases were required at, or close to sea-level (wherever possible) to ensure a maximum lifting capacity for the airships (http://www.airshipsonline.com/sheds/South_Africa.htm; see also http://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/imperial/images/Imperial%20Map.gif, accessed on 12 November 2013). Criteria for the selection of bases also included the availability of spacious, open land without any obstructions such as high hills and mountains, near an urban centre. Other matters to be taken into account were the presence of radio equipment, specifications for mastheads and sheds, general logistics and the local availability of weather information and hydrogen.

The proposed base at Durban

It was reported as the main news item in the Natal Mercury of 28 September 1927 that Durban was to become the airship port of South Africa. (See also Wilks, 1977, p 174). A point of philatelic interest is that there is a very rare South African stamp in the 1930-45 series which has a so-called 'airship flaw'. The 2d Suid Afrika (Afrikaans language) stamp depicts the Union [Government] Buildings in Pretoria, with a dark object resembling an airship flying over the left-hand side of the buildings. It seems that no South African stamp commemorating the Imperial Airship Scheme was ever issued.

The plan for Natal (now the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa) was to build a mooring mast and aerodrome at Compensation Flats, slightly to the west of Shaka's Rock on the Natal North Coast.

Negotiations with regard to the purchase of some 300 acres (121 ha) on the Compensation Flats are said to have taken place between Imperial Airways and the South African Government. The estimated cost of erecting the 200 ft (61 m) high mooring mast was £70 000.

The scheme caught the attention of the public with a cartoon entitled: 'A glimpse of the future' appearing in the Natal Mercury in October 1927. The cartoon showed a large airship descending to the Natal Air Station, with a massive hangar and a Union Jack in the background. Several two- and three-winged passenger aircraft were depicted arriving and departing, but the airship,was clearly the centre of attraction.

It can be surmised that the envisaged landing site was fairly close to the Compensation railway station.

Cape Town

The enthusiasm of the Natal Mercury was somewhat premature in respect of Durban. Cape Town, despite northwesterly gales in winter and southeasterly gales in summer as well as the proximity of Table Mountain, was also designated as a primary airship base in South Africa. Here the Cape Town City Council identified suitable land for the base in the Maitland-Goodwood area. (Today, this is the site of Air Force Base Ysterplaat and, in the 1920s, it served as a civilian airfield).

Provision was made for an airship link between Durban and Cape Town. The presence of harbours in Cape Town and Durban was of significance in the selection of both cities as bases for airships. Johannesburg, the mining, industrial and financial heartland of South Africa, was not selected; it was at too high an altitude, which would affect the lifting capacity for airships. The erection of mooring masts and communications with the airships while in South Africa was delegated to the (then) South African Railways and Harbours Administration (Klein, 1955, p 68).

Airships reconsidered

On 5 October 1930, the R101 crashed in northern France near Beauvais (see 50 Years of Flight, 1970, pp 33-4; Lanchbery, 1958, pp 62-3) and severely curtailed British enthusiasm for this form of transport. According to reports, the airship flew headlong into a 'tremendous rain-lashed gale'. She was carrying several British aviation experts and the Secretary of State for Air and was on her maiden flight (to India). The airship burst into flames after striking a hill, leaving only a few survivors. Other modes of transport gained popularity as the taste for airships waned. Rapid improvements in aircraft design, enabling longer flights to be made, as well as competition from fast mailships, hammered the final nail in the coffin for the airship programme. The Airship Division was closed at the end of 1931, thus ending a great dream (Crewe, 2009, pp 28-31; see also http://www.rmets.org/sites/default/files/hist08.pdf, accessed on 1 November 2013) without any airship landing infrastructure having yet been installed in South Africa. Other disasters involving airships brought down the French Dixmude and the American USS Shenandoah, USS Akron and USS Macon (Mooney, 1972, pp 43-4, 59-65).

The LZ 114, the last Zeppelin built for the German Navy in the First World War, but never delivered, was taken over by the French Navy as part of war reparations, and named the Dixmude. She was the most advanced Zeppelin at that time, and had been designed to bomb New York. (However, the first transatlantic flight was undertaken in July 1919 by another airship, the R34, the design of which had been copied from a captured German airship.)

The French used the Dixmude to make the first air circuit of North Africa, flying 4 500 miles (7 242 km) non-stop. German airshipmen warned the French that the Dixmude had been designed for high altitude flying in less turbulent air. On 21 December 1923, she caught fire in a thunderstorm at low altitude and crashed into the sea off the coast of Sicily. The French, like the British, then lost faith in airships. (It is interesting to note that Treusch von Buttlar Brandenfels [1931, P 222] contradicts Mooney's low altitude account of the Dixmude crash by stating that she 'crashed in flames from a great height - about 12 000 feet [3658 m] - on the south coast of Sicily, after a flight across the Mediterranean and the north coast of Africa').

Helium-filled airships

Continental airships all used relatively inexpensive, although highly combustible, hydrogen as a lifting medium. The Americans, after a bad experience with an Italian designed airship which flew into power cables and exploded, opted to use helium rather than hydrogen. America had the monopoly on helium supplies, with the possible exception of the USSR. Helium, nevertheless, was expensive even for the Americans and only has about 90% of the lifting power of hydrogen.

The Americans built their own airship, the USS Shenandoah, in 1923. The airship was actually a copy of a Zeppelin which had crashed in France during the First World War, with modifications to accommodate the reduced lifting capacity of helium, but it subsequently became apparent that there were structural problems with the airship due to these changes.

Several experts from the Zeppelin company were later relocated to the USA to assist with the design of two other US Navy airships, the USS Akron and USS Macron. On 3 September 1925, the USS Shenandoah flew into a thunderstorm over Noble County in Ohio and broke up into three sections. The navigation officer and some crew, incredibly, managed to continue to fly one of these sections as a balloon and landed safely. The USS Akron succumbed to a storm off the coast of New Jersey on 4 April 1933.

The USS Macon, in turn, was damaged and crashed off the coast of Point Sur in California during a storm on 12 February 1935. These disasters culminated in rapidly dampening American interest in airships, and increased attention was paid to fixed wing aircraft. It was only Germany, with years of experience in building hydrogen-filled airships, which persisted with an airship construction programme.

The Hindenburg

Any lingering beliefs that airships still had a future were resolved on 6 May 1937 when the Hindenburg caught fire while in the process of landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey. Mooney (1972, pp 259, 262, 271-2) argues that the cause of this accident was actually sabotage and that a bomb had been placed on board in Germany, a fact he insists was known in official German and American circles but suppressed for political reasons. Sabotage was one of a number of theories put forward to explain the fate of the Hindenburg, but what is apparent is that the age of the first commercial airships was over.

A revival

More recently, airships built with a modern design and using more advanced materials, are receiving attention. In South Africa, an example is The Hamilton Airship Company, that attempted to raise finance in the late 1990s to build a large airship in South Africa. (For more information on this, see the Airship L T A South Africa website at http://spot.colorado.edu/∼dziadeck/airship/southafrica.htm, accessed on 8 November 2013).

The well-known South African mobile phone service provider, MTN, acquired an American-built airship, 'the MTN Lightship', for airborne advertising purposes in 1997 (See http://home.intelkom.com/intouch/ archive/beyond3/html/airship.html and http://mybroadband.co.za/vb/showthread.php/166873-What-happened-to-the-MTN-BlimpAirship; and 'MTN - Where no other advertiser has dared to go!' in SA Flyer, 30 April 1998, pp 14-15. The article can be read at http://avcom.co.za/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=46329. All websites were accessed on 8 November 2013). The airship was also used to provide overhead television coverage of some major sporting events in this country. The airship was sold by MTN in 2001 and returned to the USA.

A Zeppelin NT prototype, one of only a few such craft, was shipped to Cape Town and arrived on or about 31 August 2005 (http://spot.colorado.edu/∼dziadeck/airship/southafrica.htm, accessed on 8 November 2013). The plan by De Beers Prospecting Botswana was to use the helium-filled airship (which provided a very stable work environment) to prospect for diamonds in several areas in Botswana.

The airship (D-LZFN Friedrichshafen) was prepared for flight in Cape Town, and was fitted in Gabarone, Botswana, with advanced equipment for sensing diamond-bearing geological strata. She was then flown to Jwaneng, an important diamond mining town in southern Botswana, to begin prospecting, but she was irreparably damaged on 20 September 2007 by a violent whirlwind, while attached to her mooring mast at Jwaneng. One crew member on board was injured in the incident (http.//airshipworld.blogspot.com/2007/09/zeppelin-nt-prototypedamaged.html; also http://www.carnetdevol.org/debeers/airship.html, both accessed on 8 November 2013; see also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeppelin_NT, accessed on 18 November 2013).

A hybrid airship

A current airship initiative in South Africa concerns the Dynalifter(R) which is described as a 'hybrid aircraft, part airship and part traditional aeroplane'. (For more information, see the Airships Africa website at http.//www.airshipsafrica.com/Projects/SADurban.html, accessed on 8 November 2013). This heavier-than-air craft generates lift from a combination of helium, wings and canards (additional surfaces for stability and control).

A prototype of the Dynalifter(r) was tested in December 2012 and January 2013 in the USA. Further legal and other requirements must still be satisfied before the airship' can be used commercially. A Durban firm, Airships Africa (pty) Ltd, plans to lease these airships to fly cargo between Johannesburg and Durban, and elsewhere in south and central Africa.

Aerial advertising

A small Bayer Airship was flown in a number of countries in 2013 as part of that company's 150th year anniversary celebrations (http.//www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/bayertakes-to-the-air-2013-05-10, accessed on 8 November 2013). Soweto, near Johannesburg, was chosen as the centre of operations in South Africa. The airship was regarded by Bayer as a highly visible means of attracting public attention to the festivities being held in various cities in the world. This marketing concept is not new in South Africa, where several companies make or supply tethered balloons for use as an outdoor advertising medium.

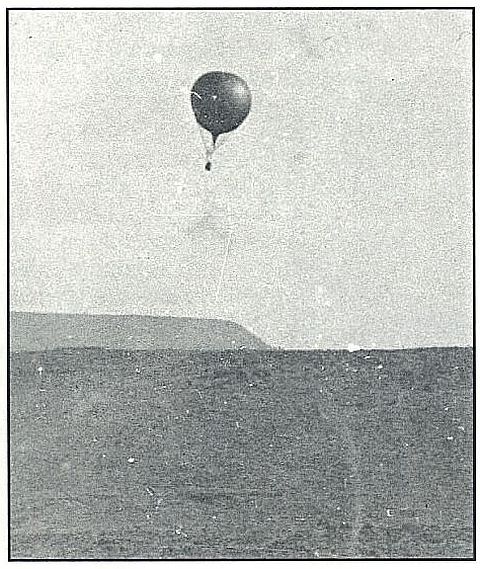

Balloons, of course, are not a new technology in South Africa. For example, they were used by the British in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) as observation posts for artillery and to determine enemy troop movements (http.//airminded.org/2010/04/19/theboer-war-in-airpower-history, accessed on 8 November 2013; see also Illsley, 2003, pp 5-16, and Spiers, 2010, pp 32-3, 106, 124 and 174). Ballooning, in the form of hot air balloons, is a growing sport and business venture catering for tourists in South Africa, although it is not without an element of danger.

The latest developments

Some experimental work on airshiptype craft has been undertaken in South Africa. One example is the Aerospace Systems Research Group in the School of Mechanical Engineering at the University of KwaZuluNatal in Durban (http.//www.rc-zeppelin.com/References.html, accessed on 8 November 2013). Three engineering students in 2009, under the guidance of their supervisor, built a prototype Hybrid Unmanned Aerial Vehicle or HUAV. The craft consisted of a Zeppelin-shaped helium-filled envelope mounted on a simple airframe with two small engines. The HUAV was technically a blimp (ie without a rigid internal structure, but which can be controlled in flight). Small blimps, amongst other airborne craft, are under consideration for anti-poaching patrols in South African game reserves plagued by rhino, elephant and lion poaching (https://fundanything.com/en/campaignsiproject-w-a-s-p, accessed on 8 November 2013).

An investigation by the CSIR (Defence, Peace, Safety and Security) commenced in 2004 on the use of high altitude long-endurance surveillance airships to monitor South Africa's long coastline (http://www.f/ightglobal.com/news/articles/south-africa-studies-highaltitude-airships-for-maritime-mon itoring-205445, accessed on 8 November 2013, and personal communication with F Anderson, Defence, Peace, Safety and Security [DPSS], CSIR, Pretoria, 18 November 2013. Note that the South African high altitude surveillance programme began in 2004 and not 2006 as indicated in the first cited source). South African designed radar and other equipment will be installed on the unmanned airships for surveillance purposes. This concept is dependent on airships of a suitable design becoming available in the not-too-distant future.

An aerostat (a tethered airship) will be used by the CSIR in the interim to test the feasibility of long endurance unmanned craft for surveillance purposes. The universities of Cape Town, Stellenbosch and Pretoria are currently involved in the design and testing of control systems and onboard electronics specifically for use in unmanned airships and other aerial vehicles.

It was announced in 2013 that NASA may, in the future, investigate climate change in the Southern Ocean by means of suborbital rockets and high altitude balloons (Personal communication with C Redelinghuys, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Cape Town, 18 November 2013; http://mg.co.za/article/2013-10-09-00-overberg-testrange-could-see-big-renewal-programme, accessed on 19 November 2013). The research project, if it proceeds, will operate from the Denel Overberg Test Range (better known as the Overberg Toetsbaan or OTB) at Arniston in the Western Cape.

Conclusion

In light of the latest developments, it would be interesting to investigate the abandoned African airship route, proposed in the 1930s, in more detail, but the aim of this paper is merely to introduce the topic to readers. It can be said that work by the Airship Division paved the way for subsequent flights by land-based commercial airliners as well as the flying boat service between the United Kingdom and South Africa. It seems that interest in commercial airships in South Africa is still current, although no such airships are in general use in this country. Smaller unmanned aerial vehicles may have a more immediate appeal, perhaps in terms of anti-poaching operations and similar law-enforcement functions, for instance in the northern game reserves of KwaZulu-Natal near Mozambique. Cost is a major consideration, however. It is very expensive to develop new aviation technology in the first place, and thereafter the hourly operating cost of high technology aerial vehicles is also high. One of the difficulties of using helium-filled airships and blimps is the current worldwide shortage of this gas, hence the rising prices for helium (Business Report, 28 November 2013).

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Mrs K Oxley of the South African Weather Service in Pretoria for her kind help in discovering and retrieving a number of the older references.

References

Crewe, ME, 'The Met Office Grows Up: In War and Peace' in Occasional Papers on Meteorological History No 8 [Reading, History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group, Royal Meteorological Society, 2009] pp 28-31.

Illsley, J W, In Southern Skies: a Pictorial History of Early Aviation in Southern Africa, 1816-1940 (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 2003).

Klein, H, Winged Courier (Cape Town, Howard B Timmins, 1955).

Lanchbery, E (ed), Neville Duke's Book of Flight (London, Cassell, 1958).

Mooney, M M, The Hindenburg (London, Hart-Davis, MacGibbon, 1972).

'MTN - Where no other advertiser has dared to go!' in SA Flyer, 30 April 1998, pp 14-15.

Public Relations Division, South African Airways, 50 Years of Flight (Johannesburg, Da Gama, 1970).

Raper, P E, New Dictionary of South African Place Names (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 2004).

Spiers, E M (ed), Letters from Ladysmith: Eyewitness Accounts from the South African War (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 2010).

'The British Airship Mission, 1927', in Meteorological Magazine, 63 (749), 1928, pp 105-7.

Treusch von Buttlar Brandenfels, H, Zeppelins Over England, translated from the German by H Paterson (London, George G Harrap, 1931).

Wilks, T, For the Love of Natal: The Life and Times of the Natal Mercury 1852-1977 (Pinetown, Robinson, 1977).

(Online sources are indicated in italics in the text).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org