The South African

The South African

'Call upon Me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you shall glorify Me.' - Psalm 50: 15 (NKJV)

Following the attacks at the Vaal River (described in the first part of this article, published in December 2015), the Voortrekkers withdrew across the river and some trekked up to the origin of the Rhenoster River. Here they out-spanned in the vicinity of a hill that became known as Vegkop. When it was reported that the Ndebele were advancing again, they formed a wagon-laager. Early on the morning of the battle, a commando went out to confront the enemy, resulting in a fighting retreat back to the laager. The impi attacked using hand-weapons, but were beaten off with fire-arms, combined with the tactical use of the laager. The attackers eventually retreated, taking all the defender's livestock and leaving them in dire straits.

Prelude

In the aftermath of the attacks at the Vaal River on 23 August 1836, the Voortrekkers at Kopjeskraal faced a serious dilemma. They wanted to return to the rest of the Potgieter trek, but dared not leave their fortified laager, in case the Ndebele should come back. A large number of their livestock had been stolen and they found themselves in a pitiful state, aggravated by the loss of family and friends (Gerdener, 1925, p113). They remained at Kopjeskraal for at least five days, and buried the victims of the attacks at both Kopjeskraal and Liebenbergskoppie.

At the end of the month, after 28 August, the Voortrekkers crossed the Vaal River to arrive at the Rhenoster River not later than 2 September (VDM, 1986, p45). This was a three skofts journey, covered in three days, a skoft being between 32 and 38 km per day for oxen in good condition (Kotze, 1950, p70). It is presumably here that they were met by the members of the Potgieter Commission, whose safety was beginning to cause grave concern owing to their long absence. The Commission arrived at the scene of the Liebenberg massacre and followed the tracks of the wagons from there.

Shortly after these events, the Potgieter Trek split in two, with one section going south to the Vals River, and eventually towards Blesberg (Thaba Nchu). The other section moved another skoft eastward towards the origin of the Rhenoster River, and settled in the neighbourhood of a hill called Doornkop (Thorn Hill), due to its covering of thorn-trees (Van der Merwe, 1986, pp47-8). This hill was destined to become well-known as Vegkop.

The families scattered, in order to obtain pasture and water for their herds of sheep and cattle. During September and the first weeks of October, the Voortrekkers did not seem to have been much concerned about the possibility of another enemy attack. This changed abruptly on 17 October, when two Mantatees (baThlokoa) brought the alarming news of the advance of a large Ndebele impi (VDM, 1986, pp51-2).

The Voortrekkers realised that flight was not an option. Individual, in-spanned wagons, dispersed and on trek, accompanied by herds of cattle and sheep, provided an easy target for a swift-footed enemy. They therefore had to form a laager of wagons and rely on their own fire-power in the ensuing clash. They had only one of two alternatives: victory or annihilation (VDM, 1986, p68).

The laager was formed immediately to the south of Doornkop. Subsequently, the Voortrekkers dispatched a three-man reconnaissance patrol, comprising Nicolaas Potgieter, Jan Celliers and Joachim Botha, to scout for details regarding the advancing Ndebele. The patrol confirmed the presence of 3 000 to 5 000 Ndebele warriors, the bulk of King Mzilikaze's army. They were observed 'a few hours on horseback away', at 10 km per hour, about 20 to 30 km to the north-west of Doornkop.

Mzilikaze's motives are unknown, as he did not confide in anyone, including the American missionaries at Mosega (Kotze, 1950, p168). He was not impressed by his supreme commander Khalipi's performance at Kopjeskraal, as he was accustomed to nothing short of total victory. Mzilikaze was also well aware of the large herds of livestock that the Voortrekkers still possessed. He had ordered Khalipi to kill all the men and boys, but to capture the women and girls with the rest of the plunder (VDM, 1986, p49).

A question of command

As noted previously, primary documents from the Great Trek period are quite scarce. A number of memoirs exist, mostly recorded decades after the battle. The result is that gaps exist in the descriptions of the events that followed at Vegkop, and narratives differ quite extensively, particularly with regard to the details.

There is, for instance, a long-standing disagreement regarding the command at the Battle of Vegkop. The Celliers biographer regarded Sarel Celliers as being in charge (Gerdener, 1925, pp31-33), whereas the Potgieter family maintain the commander was Kommandant Hendrik Potgieter (Potgieter and Theunissen, 1938, pp59-61). Later historians tended to side with one leader or the other (VDM, 1986, pp90-96). Recently, Professor van Schoor of Bloemfontein has suggested that Celliers and Potgieter were each in charge of the men from their own original trek parties (Van Schoor, 1984, p9). The authority or command exercised by a Voortrekker kommandant cannot reasonably be compared to that of a modern military officer. His authority depended upon the amount of control that the majority of the burghers were willing to grant to him (Tylden, 1961, p180; VDM, 1986, p203). A burgher would be inclined to align himself with a leader who had earned his trust. Sarel Celliers was a spiritual leader who did not act in a military capacity, either before or after the Battle of Vegkop, although he participated in a number of battles during the Great Trek, including Vegkop, Moordspruit and Blood River (Gerdener, 1925, p31). Potgieter was an experienced kommandant even before Vegkop. He was a military leader against the Ndebele and the Zulu and in 1851 became one of the four Kommandant-Generals of the South African Republic (Potgieter and Theunissen, 1938, pp226-8), which strongly suggests that he had played a leading role at Vegkop.

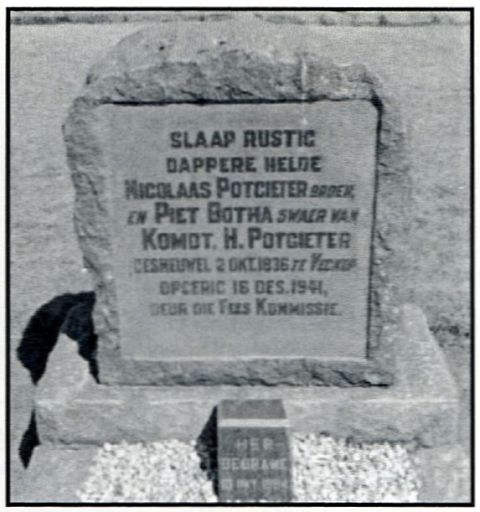

Even the date of the battle is subject to differences of opinion. On some monuments at Vegkop, the date is given as 2 October 1836, but Kotze calculated the date as having been 19 October, based upon the movements of the Ndebele impis (Kotze, 1950, footnote p153). Van der Merwe calculated the date from various other contemporary reports as 20 October (VOM, 1986, p99) and this is the date that is generally accepted today, although it is not conclusive.

The laager

Sources also vary as to the shape and size of the laager, which comprised approximately 46 wagons in a circle, with a square of another four wagons in the centre. Van der Merwe calculated the outer perimeter of the laager to be 190 metres and the diameter, 60 metres, providing an area of about 2 600 m2 within the circle, certainly large enough to accommodate the horses, but not the livestock (VOM, 1986, p58). Some Voortrekkers were aware of the ratio between the circumference and the diameter of a circle, perhaps from the Bible (1 Kings 7 verse 23), and made use of this knowledge during the construction of the laager (Tylden, 1961, p182). To build the laager, the shaft of one wagon was pulled up between the rear wheels of the wagon in front of it and tied with rieme (raw-hide thongs) and chains. Poles were planted behind the wagon wheels and similarly secured. The openings underneath the wagons, as well as the spaces between wagons, were sealed off with thorn-trees, pulled in from the outside with the forks facing inside, and also secured. At one point a gateway was constructed, by putting two wagons end-to-end, with an opening wide enough for a horseman to pass through. Access was controlled by the use of a large branch.

The square of four wagons in the centre of the laager and their tents were covered with animal skins and wooden planks to protect the women and children from assault from above by throwing assegais. The canvas tents of the other wagons were covered with reed-mats and tarpaulins in laminated composite plates, which proved impenetrable to assegais.

In considering the topography of Doornkop (Vegkop), it provided no tactical advantage for either combatant in the battle, although the site was useful as an observation point for the Voortrekkers (Tylden, 1961, p182). On one side, there was a numerically superior force armed with hand-weapons and, on the other, a much smaller force using state-of-the-art firearms, excluding artillery. The weaponry determined that the conflict would be decided at short range. The effective range for throwing assegais is about 40 metres (Tylden, 1953, p137), and that for a muzzle-loader firing buckshot about 80 metres (Curson, 1960, p93). The long grass surrounding the laager was flattened as an extra precaution, by directing animals and drawing branches over it (De Jong, 1981, p50). The stage was set.

The Ndebele advance

Few of the Voortrekkers slept during the night preceding the attack. Many prayed and listened for any suspicious sounds. They had no illusions as to what the next day would bring, as the memories of Liebenbergskoppie and Kopjeskraal remained vivid. Early in the morning, a commando comprising all able-bodied men (about 36) went out in search of the Ndebele. Among them were Hendrik Potgieter, Sarel Celliers, J L Botha, Jacobus Potgieter, Hermanus Potgieter, Joachim Botha and Piet Botha (VOM, 1986, p60). Their objectives were to explore the possibility of preventing bloodshed through negotiation and to keep the enemy away from the laager.

Information regarding the enemy advance is rather scarce. It is not known exactly where the impiwas located, but it was approximately an hour on horse-back (10 km) from the laager. The Voortrekkers found the Ndebele sitting down and having breakfast. Using a Khoikoin interpreter, they asked the indunas why they wanted to harm them. In reply the impi jumped to their feet, shouted 'Mzilikazi', and charged.

The Ndebele attempted to encircle their enemy by using the trusted 'horns of the bull' formation. Their tactics were rather inflexible. An impi attacked with the short stabbing assegai and the throwing assegai was only used when meeting stiff resistance (Tylden, 1961, p181). The mobility of the 'horseman with a gun' gave the Voortrekkers a distinct advantage, and they managed to keep out of reach of the impi, in spite of the vigorous pursuit by the latter. No Voortrekker was injured during the initial Ndebele advance and running-battle, which, according to the American missionaries, lasted for about three hours (Kotze, 1950, p167).

During the advance of the Ndebele, the Voortrekkers repeatedly dismounted, fired a volley, remounted and retired while reloading their muskets. Once the reloading was completed, the horsemen would dismount again and repeat the entire process. Sarel Celliers recorded that he fired about 46 shots during the Ndebele advance (VOM, 1986, pp64-5). If this was an average, about 1 600 shots could have been fired at the impi, causing massive carnage as the Voortrekkers were trained from their youth to be competent hunters and to use their ammunition sparingly. It is estimated that about 200 warriors were killed along the way, according to Investigatus, a reporter for the Graham's Town Journal, who visited the Voortrekkers immediately after the event (VOM, 1986, p65). The Ndebele lost a number of their leaders during this early phase of the battle, which would later be felt during the subsequent attack on the laager (Tylden, 1953, p138).

The fighting retreat of the Voortrekker party brought them right back to the laager just as their ammunition started to run low. They galloped to the gate and immediately prepared for the attack that was to follow. On approaching the laager, however, some members of the commando panicked and broke away. Thus Louw du Plessis, 'Kort' Floris Visser and 'Klein' Marthinus van der Merwe did not participate in the defence of the laager, but returned unharmed a few days later, henceforth to be known as the lafaards (cowards).

The attack on the laager

Last minute preparations for the expected attack were hurriedly completed within the laager perimeter. Sarel Celliers offered encouragement by reading from Scripture, Psalm 50 verse 15. Martha van Vuuren intoned and all joined in singing Psalm 130 verse 1, 'Uit diepten van ellenden ... 0 Heer, aanschouw mijn smart' ('From the depths of my distress ... 0 Lord, observe my anguish .. .' -VDM, 1986, p70).

Every man went to his designated post, where the muzzle-loaders were rinsed and equipped with fresh flintstones. A dirty barrel could slow down the loading process considerably (Tylden, 1961, p182). A good flintstone would ignite about thirty shots, or more (Tylden, 1957, p207). Black powder was poured into bowls and bags with lopers (buck-shot) placed alongside. Sources agree that there were less than 40 able-bodied men in the laager, a number that probably included youths who were able to shoot, as well as servants. Some women, who had grown up on the frontier, also knew how to handle a musket and were prepared either to fire or to load for their husbands. With two muzzle-loaders and an assistant, an experienced marksman could maintain a firing rate of four shots per minute (Tylden, 1953, p137; Curson, 1960, p93).

Meanwhile the impi had surrounded the laager and divided into three groups, sitting well out of range for a musket, at about 500 metres. Another group began to round up the livestock. They were in no hurry to attack, after fighting a running-battle for some hours. The warriors were hungry; about 80 oxen were immediately butchered and devoured raw. Some of the warriors honed their assegais on stones.

The tension inside the laager was palpable. Various accounts attest to individuals trying to entice the Ndebele to commence with the battle, by raising a white or a red flag. They had orders not to fire until the enemy had advanced to about 20 to 30 metres from the laager.

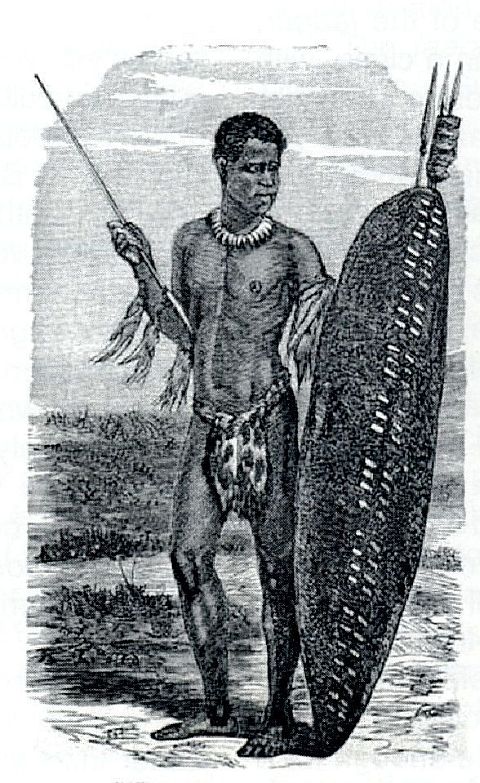

Suddenly and without warning, the impi arose and attacked the laager from all sides. The charging Ndebele impi in full battle-dress were an awesome sight. With animal skins and tails dangling, they approached, carrying their large shields and assegais. In unison, they hit the shields with the assegais and uttered fearsome battle-cries. This was a supreme test for even the most steadfast Voortrekker (VDM, 1986, p71).

The impi converged as they came towards the laager, eventually running shoulder-to-shoulder. When the defenders opened fire with buckshot, it was almost impossible not to hit several warriors with each shot, and still the impi kept charging over the bodies of their fallen comrades. Those who survived reached the thorn-trees forming the outer perimeter of the laager. They tried to remove the branches or to cut the thongs with their assegais, but did not succeed. The warriors also endeavoured to dislodge individual wagons by pulling them out of the laager or trying to overturn them. These attempts also failed, but some of the wagons, it was discovered later, had been displaced by as much as 30 cm. Warriors placed their shields on the branches in an attempt to climb over them onto the wagons, while others tried creeping underneath the branches into the laager, but not one succeeded in entering the laager alive (VDM, 1986, P 74).

Within the boundaries of the laager, the horses became frightened by the battle noise and started running around, kicking up clouds of dust. This, combined with the combustion products of the black-powder, a white smoke of potassium carbonate and potassium sulphate/sulphite (Davis, 1943, p43), soon reduced visibility significantly.

Estimates for the time and duration of the attack vary, but it seems to have started around noon and lasted for approximately half an hour. When the Ndebele realised that they were not succeeding in gaining access to the laager, and losing more and more men, they became disheartened and changed their tactics. Their stabbing assegais were ineffective, so they resorted to using their throwing assegais, lobbing them over the wagons and into the laager. After the battle, more than 1 100 assegais were found inside the laager. These weapons caused the largest number of casualties among the Voortrekkers.

Information on the final phase of the battle differs amongst the sources. According to some reports, the enemy began to leave the battlefield, but the defenders continued shooting, while organising a mounted pursuit (VDM, 1986, p78-9), which lasted until sunset, with the enemy in full flight. In the evening Sarel Celliers conducted a thanksgiving service for the traumatised survivors of what was an appalling ordeal (Gerdener, 1925, p40).

The aftermath

The attack was beaten off, but from all perspectives it was a Pyrrhic victory. The Ndebele left with all the livestock of the Voortrekkers, excluding their horses. There were no draught-oxen or milk-cows for the Voortrekkers and with no sheep to slaughter, they were facing starvation. Sarel Celliers wrote how his children cried for food, and that he had nothing to offer them (Gerdener, 1925, p115).

Two Voortrekkers had been killed in the fighting. They were Nicolaas Potgieter and Piet Botha (brother and son-in-law of kommandant Hendrik Potgieter, respectively). They were buried the same evening on the battle site and their restored grave may be seen to this day. Fourteen others were wounded and a few horses killed. The suffering of the wounded was terrible, as the Voortrekkers had no medicines, except some boererate (home remedies).

The material losses were devastating. The Ndebele took some 6 000 cattle and 41 000 sheep and goats. Three days after the battle, a commando was sent to pursue the fleeing Ndebele to retrieve some stolen animals, but it was unsuccessful (VDM, 1986, pp80,87). During the battle, no assegais had penetrated the tents to the inside of the laager, but on the perimeter many wagons had been severely damaged with some wagon-tents receiving up to a hundred holes from the assegais.

The number of fatalities among the Ndebele is uncertain, but is estimated to be around 400, with 184 bodies found around the laager (Kotze, 1950, p167). With decaying corpses nearby, the Voortrekkers had to move their wagons to the Rhenoster Spruit about 400 metres away, by inspanning their horses, or by man-power as they had no draught animals.

The Voortrekkers realised that they required assistance urgently. Some survivors, with 34 wagons, arrived at Blesberg a few days before 1 November, according to Investigatus. How they subsequently obtained draught-oxen for this move is unknown, but van der Merwe supposed that they met up with other Voortrekkers closer to the Vaal River (VDM, 1986, p104). Hendrik Potgieter had sent his brother, Jacobus, to Blesberg to request oxen from other Voortrekkers, the Reverend Achbell and Chief Moroka of the Barolong people. Assistance in the form of 200 draught-oxen arrived after two weeks and the remainder of the impoverished Voortrekkers arrived at Blesberg around the middle of November 1836. Upon their arrival at Blesberg, both groups were received in a most friendly way by Achbell and Moroka, who presented them with the necessary supplies. For this gesture, the Voortrekkers remained grateful for generations.

In January 1837, a commando was organised to attack Mzilikazi's military kraal at Mosega, in order to recover the livestock taken at the Vaal River and Vegkop. About 6 500 head of cattle were retrieved by the Voortrekkers during this expedition.

Conclusion

The Battle of Vegkop was a critical point in the migration of the Voortrekkers to the interior of South Africa. It can be argued that, had the Ndebele succeeded in overrunning the laager and exterminating the Voortrekkers there, the entire Great Trek would have been in jeopardy (De Jong, 1981, p48). The 200 Voortrekkers who lived through the ordeal were fortunate and ascribed their survival to nothing short of divine intervention. For some inexplicable reason, the Ndebele commander, Khalipi, decided against employing the conventional Ndebele tactics of attacking under cover of darkness (Becker, 1968, p8). Likewise, the supreme commander could have laid a siege on the laager, but he preferred to attack (VDM, 1986, p78).

So significant is the Battle of Vegkop that it has been compared to the Battle of Blood River (16 December 1838).

The number of wagons in the laager at both battles was similar. At Blood River, there were 64 and, at Vegkop, 50. However, the number of defenders within the laagers was vastly different. At Blood River, there were 467 able-bodied white men and some auxiliaries, while, at Vegkop there were only 40 men, plus an estimated 160 women and children. Likewise, the enemy at Blood River amounted to 10 000 to 12 000 Zulus, and at Vegkop, 3 000 to 5 000 Ndebele. If these figures are accurate, the Voortrekkers were outnumbered 20:1 at Blood River and, at Vegkop, 100:1 (De Jongh, 1979, p34).

At Blood River the Voortrekker commander, Chief kommandant Andries Pretorius, used defensive tactics in an offensive strategy. He deliberately entered hostile country in order to entice King Dingane to attack his laager, and he was ready for such an assault. At Vegkop there was nothing of the sort, it simply was a matter of survival.

Special acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Ilze Cloete, Ditsong National Museum of Military History, for assistance with this article.

References

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org