The South African

The South African

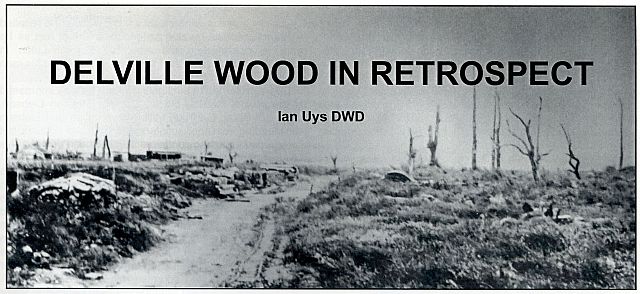

A question posed is what is the relevance of the Battle of Delville Wood, which took place a century ago? There is no one answer, as many factors come to mind. It was the baptism of fire for a new, untried brigade from South Africa, who acquitted themselves superbly. Their commander, Brigadier General Henry Timson Lukin CMG DSO, had selected young men, most of whom were under twenty years of age, to fight in France. The spirit among the youngsters was such that they would not be beaten by anyone. After the brigade had been shattered by days of high explosive shelling, reaching a crescendo of 450 shells a minute, a German officer recalled how young survivors stood up from the mud and fought them hand-to-hand.

The brigade was recruited at Potchefstroom and comprised men from every corner of the country: The 1st Battalion from the Cape, the 2nd Natal, Border and the Orange Free State, the 3rd from the Transvaal and Rhodesia and the 4th from various Scottish units. The pride of South Africa's premier regiments was apparent in the various companies, of whom about 15% were Afrikaners.

After arriving in Hampshire, England, the brigade was sent to Egypt where they fought and beat the Senussi at the Battles of Halazin (Mersa Matruh) and Agagia in January and February 1916. They sailed to Marseilles and then entrained for the north of France. The brigade received training in trench warfare near Armentieres, Belgium.

The brigade was attached to the 9th Scottish Division, which had lost one of its brigades at the Battle of Loos. Initially the South Africans were resented by the Scots, but when it became apparent that they were crack shots and that some couldn't speak much English they were welcomed. Colonel Winston Churchill commanded an adjoining regiment.

The Somme

In mid-June, the division marched south to take part in the 'Big Push' - an allied offensive in the Somme River area. From 24 June, the British artillery bombarded the German trenches, which generally overlooked the British line and, on 1 July, a massive offensive was launched. The Germans had been well dug-in and weathered the bombardment, to emerge with machine-guns and mow down the advancing troops. The British incurred 60 000 casualties, of whom almost 20 000 were killed.

The Springboks, as the South Africans were known, were in reserve, and were then mobilised. On Monday, 10 July, the 4th Bn, SA Scottish, entered Trones Wood. The following day their commander, Lieut-Col Frank Jones DSO, was killed by a shell-burst at the mouth of his dugout. This was a sobering event for many youngsters, who realised that if a colonel could die so easily, so could they.

On 14 July, the 2nd Bn, from Natal, were in Bernafay Wood, where they suffered over 500 casualties from head injuries due to shells which burst in the trees and showered them with shrapnel and splinters. Private Eddie Fitz earned the Military Medal as a linesman for joining telephone wires which were continually being broken by shell fire.

That morning the two Scottish brigades had attacked the village of Longueval (and its adjoining Delville Wood) and incurred heavy casualties. The Germans had fortified the village and had tunnels connecting houses to each other and into the wood. Delville Wood was named because of being the Bois de fa Ville (Wood of the village). Inside were numerous roadways, or rides, cross-crossing each other for bringing out wood.

The 1st, Cape, Battalion was sent as reinforcements and fought their way into the village. During the street fighting, Private Boysie Nash from Steytlerville charged into the enemy lines and was killed, Lieutenant Chauncey Reid from Knysna threw a hand-grenade into a bunker, not realising that it was an ammunition store, and was blown up fortunately he survived.

Into the Wood

The following morning, Saturday, 15 July, Lieut-Col William Tanner led the rest of the brigade into the wood. He deployed them around the perimeter and told them to dig in. Eddie Fitz dug with his hands and said that he'd struck water, only to find that he was digging in his own blood. He was to be among the first casualties evacuated.

The 2nd Bn Natal 'B' Company was decimated as they headed north up Strand Street. Captain Ernest Barlow, founder of the industrial firm, was blown up and evacuated, never to fully recover. Lieutenant Walter Hill's platoon was captured when they ran out of ammunition. While being escorted to the rear, Hill attacked a guard and fought his way back into the wood, where he was killed two days later. He was later recommended for a posthumous Victoria Cross.

On the opposite side of the wood, the south-east, there had been confusion as the Transvalers of the 3rd Bn 'A' and 'B' Companies thought that French helmets were opposite them. They turned out to be German coal scuttle helmets! Captains Richard Medlicott and Leonard Tomlinson led, respectively, 'B' and '0' Companies in a charge which overran the enemy trenches. They took 135 prisoners in the raid then retired to their perimeter positions. Tomlinson earned the DSO for this exploit while Lieutenant Francis Somerset's bravery was also noted.

During the morning of Sunday, 16 July, the Cape's 'A' and 'B' Companies attacked the north-west corner of the wood. The Germans had it heavily fortified and their fire broke up the attack. Captain George Miller was among those killed. Lieutenant Arthur Craig lay wounded in front of the German positions. Private 'Mannie' Faulds from Cradock, together with Privates George Baker and Alexander Estment, went to his rescue and managed to drag him to safety. Craig later commended Faulds for his bravery. For this, and a subsequent rescue two days later, Faulds was awarded South Africa's first Victoria Cross of the First World War.

Early on the morning of 17 July, General Lukin and his staff officers visited the wood to ascertain the position at first hand. Tanner informed him that it had been impossible to withdraw troops from the perimeters due to the heavy German counter-attacks. The intention had been to leave strategically placed machine-gun posts only. General Lukin then telephoned the Division's commander, Major-General W Furse, to request a withdrawal as his men had been in the front lines for 48 hours. Furse told him that there were no reserves at the time and that the position was 'to be held at all costs'.

At 14.00 Major Harry Gee of 'D' Company, 2nd Bn, sent a company runner to Tanner to inform him of their dire straits. Private Garnet Tanner ran through shell bursts until one blew him up in the air. He turned a somersault and came down head first into the hole it made. The ground collapsed and buried him but he waved his legs until he was dragged out. He delivered the message and returned unscathed, to earn a DCM later for his courage.

Shortly before 19.00 Lieut-Col Tanner was shot in the upper thigh. He was carried from the wood shouting that he wished to remain with his men. Lieut-Col 'Frank' Thackeray, whose father had won the VC in India, then took command. He had been a cowboy in America and later served in the Matabele War in Rhodesia and the South African War. The Germans, meanwhile, had retired from the wood fringes as artillery was being brought from as far as Verdun to flatten the wood.

Endurance

Early the following morning, on Tuesday, 18 July, the South Africans and Scottish brigades met up in the north-west corner. Then the enemy guns opened up and for eight hours bombarded Delville Wood. Many men were buried in the trenches in which they crouched.

As telephone wires had proved useless, runners were used instead. Private Harry Cooper, 18, of the 3rd Bn 'C' Coy had won a bravery medal as a Boy Scout for stopping a runaway horse in Johannesburg. In the wood he recalled a Vickers machine-gunner pretending to shoot him as he ran. He delivered a message to General Lukin in Montauban, who, with tears in his eyes, asked after his men in the wood, which by then resembled a volcano.

Cooper returned to the fighting where he was impressed by the Jewish medical officer, Captain Stephen Liebson, brother of Sarah Gertrude Millin. He recalled that Liebson was bleeding from shell splinters in the lobes of his ears, but disregarded them and continued ministering to others at his aid shelter in Longueval.

Private Albert Loubser, 33, from Sir Lowry's Pass, was a large Afrikaner who acted as a stretcher bearer. His strength and bravery became legendary as he carried wounded men out of the wood, at times carrying one under each arm and another on his back. When he stopped to rest, his name was taken by an officer and he thought he'd be on a charge, but instead was later decorated with the DCM.

On the northern perimeter, Major Burges of the Cape Town company ordered Lieut Errol Tatham of Pietermaritzburg to fetch reinforcements. Burges was then killed by a shell. Tatham brought some men, then was shot, but managed to reach a shell hole in the middle of the wood, where he died. Lieut-Colonel Dawson sent Second-Lieutenant Edward Phillips and his Trench Mortar Battery men to bolster the defence. Without them the wood would possibly have fallen.

Padre Eustace Hill was berated for making tea and hot bovril as his fire might attract German shells. He ignored this as the wood was wreathed in smoke and bursting shells. When he called for stretcher bearers, he shouted, 'Do you believe in God? If you do, follow me!' One reluctant man replied, 'It's all very well for you, father. If hit you know where you'd go.'

When the bombardment ceased, three German regiments attacked from the north and east. They broke through the thin Springbok line in the north and swept through the wood, taking those on the southern flank in the rear. In the east, Captain Medlicott managed to hold on while, in the west, Col Thackeray defended the headquarters trench with remnants from all battalions.

Early on 19 July fresh German troops attacked Medlicott's cut-off Transvalers. The latter fought until they ran out of ammunition and were forced to surrender. Among them was Private Vic Wepener, 19, who would earn the DSO as a major in the Imperial Light Horse at Bardia in the Second World War. Four officers and more than 200 other ranks were taken prisoner and sent to Germany.

Thackeray and his defenders fought on, though virtually surrounded. He was assisted by Second-Lieutenants Garnet Green (2nd Bn 'C' Coy) and Edward Phillips. Thackeray fought like a private with mills bombs, rifle and bayonet. He inspired and led his men, shouting their war cry, and at times going out to drag wounded men to shelter.

The Sixth Day

On 20 July, Thackeray sent a message to Lukin that his men were on their last legs. 'I cannot keep some of them awake. They drop with their rifles in their hands and sleep in spite of heavy shelling. We are expecting an attack. Even that cannot keep some from dropping down. Food and water has not reached us for two days ... ' Eventually, at 18.00 they were relieved by the 3rd Division. Three wounded officers and 140 men were all that remained of the 121 officers and 3 032 men of the brigade who had begun the fight. Garnet Tanner recalled that some of the battle-hardened relieving British troops looked at them and wept.

Thackeray would be recommended for the Victoria Cross, but was awarded the DSO. Phillips and Green each earned a Military Cross.

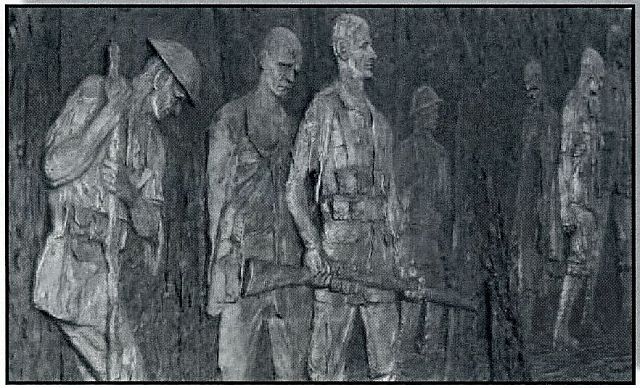

Private David Hogg (1st Bn 'D' Coy) later wrote, 'But I did not realise that we were making history. To me it was chaos with hell a-popping. And I think of the wonderful lads, most of them youngsters, who stayed behind in the wood. There is no more solemn moment in war than the parade of men after battle. Those survivors who assembled at Happy Valley were too weary and broken to realise how great a thing they had done, but tributes came to them from high quarters.'

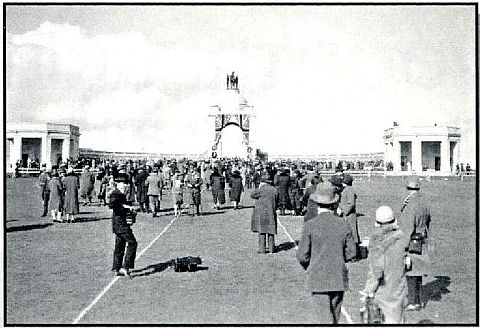

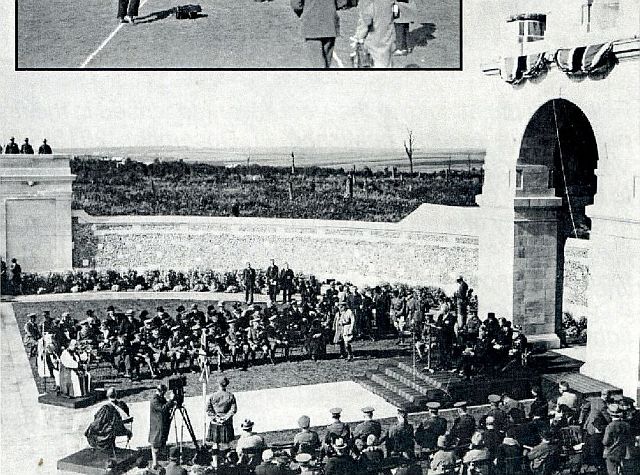

Two days later, General Lukin took the salute as 780 survivors marched past. He had tears running down his cheeks, as he knew the mothers and fathers of many of those who had died. A shock went through South Africa. Normally, there are 30% casualties when troops are withdrawn. At Delville Wood, 85% of the officers and 77% of other ranks were casualties. The Natal officers had 100% casualties.

The brigade served until the end of the war. Many of the Delville Wood survivors would die in those two years. Among them was Lieut Garnet Green, who was killed in a rearguard action at Gauche Wood during the March 1918 German offensive. Shortly afterwards, the brigade was overrun at Marrieres Wood, where Captain Liebson was among those killed. General Dawson and the remainder were taken prisoner. The reconstituted brigade ended the war at the spearhead of the British advance.

General Furse had a report drawn up about the Delville Wood battle. It was fact finding rather than fault finding and sought suggestions for improving tactics, logistics, weapons, artillery and mortar support, snipers, reconnaissance, medical arrangements and communications. The lessons learnt would prove of inestimable value in the coming battles.

Those who survived ...

As a platoon commander during the Border War I had no experience of large scale strategy or tactics so am not qualified to comment on whether or not the battle saved the British front. Had the Germans broken through at Delville Wood it is conjectured that they would have taken the artillery positions and enfiladed both the British and French trench lines. Others dispute this. What I can comment on was the spirit of comradeship I found among the veterans. It has been my privilege to meet many of the men who took part in the battle and to hear their recollections.

While in a pub with a group of them they joked about the day they entered the wood - one of them had torn his trousers on barbed wire and they had teased him about his pink underwear. Maurice Cristel told me that he had survived by walking around during the bombardment looking for his friends. Incidentally, Maurice died aged 91 on the squash court. Eddie Fitz quipped that Maurice had committed suicide. Harry Cooper recalled the wry humour in the wood. Someone had written in chalk on a large and a small unexploded shell 'The long and short of it!' Corporal Lilford said that Second-Lieutenant Somerset insisted that his men shave and tidy themselves, as a corpse looked bad enough without them making themselves look worse when their time came. Somerset was killed on 20 July before the relief.

These survivors, this 'band of brothers', formed the nucleus of the reformed 1st South African Infantry Brigade and passed on to the men who came after them their spirit of comradeship and the courage to hold on at all costs.

Why did South Africa commemorate Delville Wood Day for so long? I believe it was mainly to honour the steadfast courage of so many who had paid the supreme price. Delville Wood was purchased and became a small part of South Africa in France, to be held forever as a tribute to the brave men from our shores who fought for freedom from tyranny in a far distant land. It has since commemorated the South Africans who fought in the Second World War and Korea as well. The recent symbolic burying of a black South African soldier of the SA Native Labour Corps who died during the First World War brings together all of our nation in tribute to our gallant soldiers.

Though all the men of the old First South African Infantry Brigade are gone, the legacy they have left to us is their belief in the undying spirit of youth and comradeship under all circumstances.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org