The South African

The South African

Even though South Africa was a comparatively young country with a small population during the First World War (1914-18), it was still able to make several small but significant contributions to the Allied cause. One such event took place during the first year of the war. This was the story of the search and elimination of the German light cruiser, the SMS Königsberg, aspects of which are as interesting as the more famous hunt for the German battleship, the Bismarck, in the Second World War (1939-45). In both cases the captains of the respective ships knew that the Royal Navy would gather from every direction in an attempt to trap their quarries. In both cases, even though every effort was made by these captains to elude such a trap, the Royal Navy eventually emerged victorious. In the case of the Königsberg, the action took place fn the Rufiji Delta, a desolate region of river swamp and jungle on the east coast of Africa, where the cruiser was hiding as she awaited repairs. To locate and destroy her, the Royal Navy made use of the expertise of two exceptional, and very different, South Africans. They were Denis Cutler, an aviator, and P J Pretorius, a hunter. Very little has been published about the role of these two men - one of English descent and born in London, the other of Dutch descent and born in what is today known as Limpopo Province. The aim of this article is to highlight this neglected South African story of the First World War. It is not intended as a formal account of the entire operation launched by the Royal Navy against the Königsberg.

SMS Königsberg

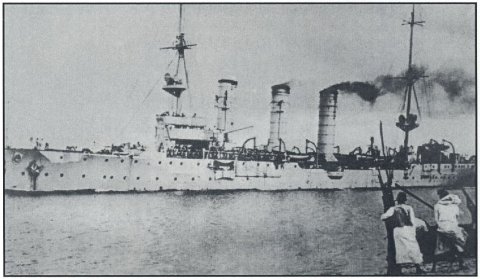

The Königsberg was launched at Kiel in Germany in 1907. The ship, one of the Imperial German Navy's most sophisticated light cruisers, was capable of a speed of up to 25 knots and had an engine capacity of 13 500 Hp and a displacement of 3 600 tons. Her main armament consisted of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 inch) guns and two 45.3 cm (17.7 inch) torpedo tubes, and her secondary armament comprised eight 4.7 cm guns and four machine-guns. She had a crew of 322 officers and men under Commander Max Looff, who would later be advanced to the rank of Captain.

In June 1914 the cruiser arrived in Dar-es-Salaam, the capital of German East Africa (Tanzania), on a flag-showing mission. There she became a proud symbol of German imperial power to the resident German community in East Africa. A month later, Looff received orders that, in the event of war, the Königsberg was to launch immediate attacks on enemy shipping in the Indian Ocean. She would adopt a strategy referred to as Kreuzerkrieg (cruiser warfare), involving hit-and-run forays on Allied merchant ships by fast and heavily armed cruisers operating independently of a fixed naval base, and replenishing all fuel and other supplies from the holds and bunkers of the ships that were attacked.

The Cape of Good Hope Squadron, Royal Navy

Well aware of the danger posed by the Königsberg in the event of the outbreak of war, the Royal Navy despatched the Cape of Good Hope Squadron, based at Simon's Town in the Cape, Union of South Africa, and under the command of Rear-Admiral Herbert King-Hall to the Indian Ocean to counter any aggressive act on her part. The three ships which initially formed the squadron, His Majesty's Ships Hyacinth, Astraea and Pegasus, were undeniably inferior to the German cruiser in all aspects of armament, range and speed. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, it had not been considered necessary to allocate any of the more modern cruisers of the British fleet to this part of the world.

At the onset of hostilities in August 1914, the Königsberg initiated its Kreuzerkrieg strategy and almost immediately left a trail of sunken Allied ships in her wake. Every effort made by the Cape of Good Hope Squadron to hunt down the elusive raider was unsuccessful. In September 1914, disaster struck when the Königsberg turned its attention to the British squadron, by attacking and sinking the Pegasus as it lay at anchor off Zanzibar. This was a direct blow to British naval prestige and led to a doubling of efforts to locate the German ship.

In hiding

Soon after her successful attack on the Pegasus, the Königsberg went into hiding to await a much needed refit; the use of inferior coal stocks looted from Allied ships had caused serious damage to her boilers. A preliminary search for the German cruiser led the Royal Navy to conclude that she had to have taken refuge in the network of rivers which form the delta of the Rufiji River, south of Dar-es-Salaam. The British Admiralty ordered that the destruction of the Königsberg take precedence over all other military considerations in the East African theatre.

To carry out a successful raid on the Königsberg where she lay in hiding, Adm King-Hall had to confirm suspicions that she was indeed in the delta, and find a means of locating her position precisely. This was no mean feat as the cruiser was not an easy quarry. Cdr Looff had taken every precaution to hide any evidence of the ship's presence in the delta. Her decks and superstructure were covered in foliage and her bodywork dazzle-painted so that, unless spotted at close range, she was well camouflaged against her jungle backdrop. The crew had also removed the torpedo tubes and placed them at the mouth of the river, ready to be used against any British vessel that might venture too close. Under these uncertain conditions, the successful location and destruction of the Königsberg seemed to point to an amphibious operation into the delta, but, as the disastrous attempt to land an Indian Expeditionary Force at Tanga in November would show, this kind of operation was fraught with danger. To attempt it without a thorough survey would be a frank invitation to failure.

Aerial reconnaissance

King-Hall first sought the assistance and expertise of a private aviator in the Union of South Africa, Denis Cutler, who was taking fare-paying passengers on short flights around Durban Harbour in a Curtiss 90hp Flying Boat Type S. The Royal Navy commander planned to use an aircraft to find the Königsberg and then either to bomb the cruiser where she was moored or to provoke her into sailing out to sea, where his own ships could then deal with her. On his return to South Africa, King-Hall arranged for Cutler to travel to Simon's Town where he was requested to place himself and the aircraft, the property of Mr Gerald Hudson, at the disposal of the Royal Navy for the duration of the operation.

In terms of the agreement reached between King-Hall and Cutler, the Admiralty would pay the sum of £ 150 per month for the hire of the aircraft and cover the full risk of the aircraft (£2 000) in the event of it being damaged as a direct result of enemy action. The Admiralty and Cutler would share the risk should the aircraft sustain damage by any means other than enemy action. On this basis, Cutler was recruited into the Royal Naval Air Service and granted the temporary rank of sub-lieutenant. On 6 November 1914, the Curtiss seaplane was loaded onto the British armed merchant cruiser, the Kinfauns Castle, at Cape Town. During the voyage north, the original ailerons on the aircraft's wings were damaged in heavy weather and the ship had to dock at Durban to fit replacement ailerons from a second Curtiss aircraft being stored there.

By then, the Royal Navy had supplemented the Cape of Good Hope Squadron with more modern ships and the Kinfauns Castle rendezvoused with the cruiser HMS Chatham on 9 November at Nicoro Island, nineteen miles (30 km) north-east of the Rufiji Delta. Cutler was then assigned a young midshipman, A N Gallehawk, to be his mechanic, observer and pupil. Cutler spent four days working on the aircraft, which the sailors nicknamed 'The Cuckoo'. The hot weather of the tropics began to affect the performance of the aircraft, and minor leaks had to be repaired before the first flight could be launched. On 19 November, Cutler took off and headed in what he believed to be a south-westerly direction. Not having been issued with a compass, he did not know that he was flying in a more southerly direction than he had estimated and thus he reached the shore some distance south of the delta. The futile initial search depleted his fuel and he was forced to abandon the mission and head out to sea to avoid capture. He made a forced landing at Okusa Island, 30 miles (48km) south of Nicoro. Fortunately, the crew of a local sailing boat reported sighting an aircraft heading south to the Officer Commanding the Chatham, Capt Drury-Lowe, and launches were immediately sent out to rescue both Cutler and the aircraft.

Repairs to the seaplane were made quickly, but the cooling radiator for the Curtiss Ox engine needed to be replaced. In desperation, the cruiser, HMS Fox, was despatched to Mombasa where a Model- T Ford automobile was commandeered for its radiator. The radiator was duly removed from the automobile and fitted onto the seaplane. This was possibly the most expensive radiator ever to be used on a Curtiss seaplane! Meanwhile, Cutler's aborted first flight had not gone unnoticed by the Germans in the delta. Looff at once issued orders for more armaments to be removed from the Königsberg and strategically placed for air defence.

Cutler took off again on 22 November and, now equipped with a compass, he set course directly for the delta. This second mission turned out to be successful. It did not take long before the Königsberg was located some twelve miles (20km) upstream. The Curtiss seaplane suffered additional damage when she landed on return from the mission and thus the Kinfauns Castle was ordered back to Durban to collect the second aircraft. Cutler was able to build up one serviceable aircraft by cannibalising parts from both seaplanes.

The British were sceptical of Cutler's report on the location of the Königsberg, so it was agreed that a passenger would accompany him on his third mission. Cdr Fitzmaurice from the Kinfauns Castle was tasked to fly with Cutler on 4 December as an observer. On their return, he confirmed the Königsberg's approximate position, but the poor performance of the Curtiss aircraft and its engine put paid to any attempt to bomb the cruiser from the air. On a final flight undertaken on 6 December, Cutler was either shot down or his aircraft suffered engine failure about 2km into the delta. It went down and he managed to swim ashore, but was immediately captured by the Germans. His mechanic, Gallehawk, who had been tracking the aircraft in an armed tugboat, managed to drive off several German Askaris who were attempting to pull the aircraft ashore. Under heavy fire, he towed the aircraft out of the delta, but it was so badly damaged that it never flew again and would eventually be consigned to the Durban Local History Museum. Cutler would spend the next three years as a prisoner-of-war in East Africa.

The covert missions of P J ('Jungle Man') Pretorius

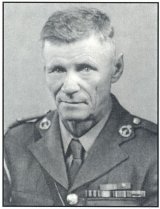

Cutler's aerial reconnaissance had confirmed reports that the Königsberg was in the delta and had established an approximate position. The German cruiser could still not be seen from the sea nor fired upon as it lay beyond the range of the British cruisers. Further attempts to attack her with Sopwith floatplanes and Short seaplanes were also botched owing to the tropical conditions. King-Hall pondered the problem. How could he attack the cruiser successfully with minimal risk to his ships? His answer came in the form of a quiet and unassuming hunter who had just arrived back in the Union of South Africa and was under observation as an unknown entity and potential enemy agent. Phillipus Jacobus Pretorius had spent a number of years hunting in German East Africa and knew the area well. For the task which King-Hall now had in mind, he seemed an ideal choice.

In January 1915 Pretorius arrived on the coast of East Africa aboard the battleship HMS Goliath and was given his first task - to fix the exact location of the Königsberg. His orders were to scout around and to find out as much as possible about the cruiser. Accompanied by a wireless operator, he was landed on Mafia Island, where he set up base camp. Six local inhabitants were recruited to assist him on his mission.

Two days after his arrival at the camp, and under cover of darkness, Pretorius and his men were landed on Komo Island, 20 miles (32 km) further into the delta. The following night, a heavy storm provided excellent cover for the party to begin their reconnaissance inland. The first mile or so was troublesome swampland, separating the river from the mainland. Beyond that, on firm ground, the small party turned westward and headed into the bush. After eight miles, they eventually came upon a wide, new road. Pretorius ordered a halt and the men were allowed to restwhile they waited for someone from the local community to pass by.

Throughout the following morning, Pretorius watched as German troops escorted columns of local porters back and forth. When an opportunity arose, he and his men captured two of the porters. They questioned them about the Königsberg. The two captives agreed to guide Pretorius to a site from which he could view the ship without being detected. From a tree, the South African enjoyed a good view of the cruiser. He could see just how well the Königsberg had been camouflaged and noted how frequently the Germans patrolled the perimeter.

Pretorius returned to the Chatham and delivered his report to King-Hall. He then learned that this had been only the preliminary part of his job and that more lay ahead. Additional orders involved calculating the bird's-eye range from the sea to the point at which the Königsberg lay moored, finding out how many guns she still had and what had happened to her torpedoes, and to make a study of the tidal patterns in the main channel and certain other subsidiary streams. A few days later, Pretorius was back in position with his two prisoners and a powerful pair of binoculars.

The hunter soon worked out that the distance from ship to shore was 17 miles (27.35 km). From his lookout tree, and with the aid of binoculars, he was able to count eight main 10.5cm guns, all of which appeared undamaged and serviceable. But there was no sign of the torpedoes. He would need to adopt bolder measures to find the answers as to their whereabouts. The plan he formulated was daring, but made possible by his experience and specialist knowledge of the area and its inhabitants. It involved contacting a local headman whom he believed would be able to assist him. His gamble paid off. The headman was keen to help and informed Pretorius that one of his sons worked on board ship as a stoker. At the cost of a basket of chickens, one was able to visit relatives working on the cruiser. Pretorius' dark and leathery complexion from years spent hunting in the African bush enabled him to disguise himself as an Arab trader, with the headman pretending to be his servant.

The two men rehearsed their role carefully and then made their way down to the ship. They were soon challenged by an armed sentry. Pretorius humbly offered his basket of chickens and made it known that his servant would like to see his son for a few minutes. After a while, the headman's son came out from the Königsberg and joined them. The youth informed them that the torpedoes had been removed from the ship and taken to a location somewhere near the mouth of the river. As there were British vessels stationed in the vicinity of the delta, Pretorius made sure that this information was quickly relayed back to King-Hall, who then ordered that all British shipping was to keep well clear of the delta.

Pretorius's next instructions were to find a navigable channel through the Rufiji and then to locate a suitable range-point in the delta. After many days of monotonous work, Pretorius eventually worked out that a route through the northern-most channel could be undertaken by shallow British monitors with a draught of four feet. He also found a suitable position from which they would be able to bombard the cruiser with their 6-inch guns. King-Hall immediately requested the services of two monitors, HM Ships Severn and Mersey, then stationed in the Mediterranean. By the beginning of June 1915, they had arrived off the Rufiji Delta.

The attack

King-Hall still preferred to draw the Königsberg out into the open to engage with the monitors, so Pretorius was given the task of deliberately trying to provoke and hopefully lure the German cruiser out. Pretorius and his party did not succeed and were almost captured when their dhow ran aground on one of the countless reefs lying between Mafia Island and the mainland. Fortunately they were rescued by a British vessel before the Germans could reach them. They almost suffered the same fate again two nights later, when Pretorius set out one last time to investigate whether the Germans had improved the defences around the Königsberg.

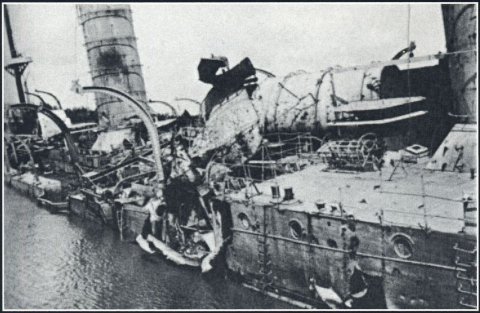

On 5 July 1915, King-Hall launched the attack on the Königsberg. The Severn and Mersey failed in their first attempt up the Rufiji to fire on the cruiser. Five days later they returned and this time they were successful. The German ship's guns gradually fell silent under a hail of high explosive and incendiary shells from the two British ships. Within a short time, she was totally engulfed in flames.

Having completed his Königsberg missions, Pretorius went on to join the Intelligence Service in East Africa and gradually became the chief scout for Lt Gen J C Smuts, who was then Allied Commander-in-Chief in that theatre of operations. He served in that capacity until he was invalided back to South Africa due to disease during the final year of the war.

In 1924, John Ingle, the former captain of HMS Pegasus, was tasked with clearing wrecks from the harbour in Dar-es-Salaam. At that time, he bought the salvage rights to Königsberg for the price of £200 and sent divers to extract the non-ferrous scrap metal from the wreck after which he, in turn, sold the rights. Salvage work continued into the 1930s, and by the 1940s the hull had rolled over to her starboard side. Salvage work continued as late as 1965 and in 1966 the wreck finally collapsed and sank into the riverbed.

The Königsberg guns in South Africa

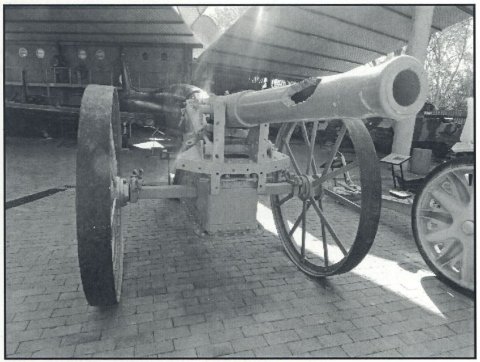

Although the Königsberg had been destroyed and her direct menace to Allied shipping and communications finally removed, the cruiser, in a sense, remained a threat to the Allied war effort in German East Africa. Looff and the survivors of his crew, along with all ten of her 10.5cm guns and valuable stores which had been salvaged, including two smaller 8.8cm guns, were placed at the disposal of Gen Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's German and Askari land forces for the remainder of the war in East Africa. Some of the guns were used on their fixed pivot mountings, others had makeshift gun carriages which were constructed in Dar-es-Salaam, and the remainder used gun carriages made by Krupp in Germany. All of the Königsberg guns eventually fell into Allied hands. Four are known to have survived until today and of these, two found their way to South Africa where they are on public display.

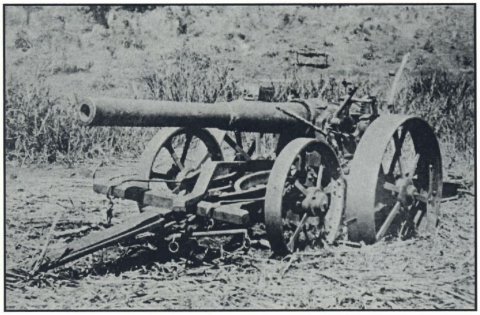

One of the 8.8cm Schiffskanone, which had originally been kept in the hold on the Königsberg for the purpose of arming German merchant ships, is on display at the Ditsong National Museum of Military History. It was used during the initial stages of the German East African campaign but was eventually abandoned by her crew in September 1916 during the South African offensive undertaken between Morogoro and Kisali. It is apparent that a shell exploded in the barrel of the gun.

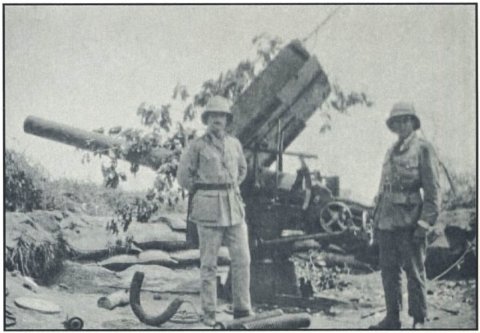

The second known Königsberg gun in South Africa is a 10.5cm gun on display at the western approach to the Union Buildings in Pretoria. A plate affixed to the gun identifies it as a 'German Naval Gun captured by the 1st South African Mounted Brigade and the 2nd South African Infantry Brigade at Kahe on 2 March 1916'. The barrel on the gun has a flange to hold a barrel shield which would fit inside the original turret where it was mounted on the Königsberg. Six of these guns were mounted in turrets, while four were mounted in unarmoured cupolas meaning that they did not contain barrel flanges. However, the identification and provenance of this gun has been the subject of heated debate. What is certain is that it is made up of parts from several different guns; at least four serial numbers have been noted on various parts of the gun. The barrel and the left recoil cylinder have the serial number 369, while the right recoil cylinder has the serial number 367. The elevation wheel carries the number 361.

The mystery of the Pretoria gun

The provenance of the gun is contested. It has been suggested that the information on the plate fixed to the gun is inaccurate. In various photographs taken of the Kahe gun, one is able to see a damaged breech as well as a large split in the barrel. In contrast, the gun in Pretoria is relatively intact, aside from a missing breech block. A study of the fate of the Königsberg gun~ has revealed that the most realistic options for the origin of the Pretoria gun are that it was one of two captured either at Mahiwa and Tabora, or it is the one accidentally destroyed by the Germans at Kondoa Irangi.

Mr Bob Wagner, a researcher in the United States who has an interest in the subject, believes the gun to be that captured at Tabora. In his view, when the forces under the command of Lt Gen J L van Deventer discovered an undamaged Königsberg gun at the collection site in Tabora, they quickly took possession of it and had it shipped to the Union of South Africa as a trophy.

Mr M C Heunis, a local expert who provided the Department of Public Works with information while the gun was being restored in 2006, believes otherwise. In his opinion, the Tabora gun could not have been claimed by British or South African forces as it had already been captured by Belgian colonial forces. He also discounted the theory that it may have been the gun captured at Mahiwa, as that gun had no flange. He believes the Pretoria gun to be the one destroyed by accidental misfiring by its crew at Kondoa Irangi on 18 May 1916. In Heunis' hypothesis, the gun was removed to Dar-es-Salaam for repairs. However, upon closer examination, the Germans deemed it to be beyond repair and buried it somewhere near the railway works. After the fall of Dar-es-Salaam in September 1916, the local community informed the British of the location, of the gun and it was dug up. Missing parts, such as a recoil cylinder, a carriage and wheels, could easily have been sourced from the other partially destroyed guns that were then in Allied hands, the guns captured at Mahiwe, Masassi, Kibata or Myuyuni. The Krupp wheels may have been the original wheels fitted to the gun or salvaged from the remains of the guns captured at Mahiwe or Masassi.

Wagner firmly believes that, on available evidence, his proposition carries weight. Heunis' premise also remains a distinct possibility. Neither argument, however, is irrefutable.

Conclusion

What is undisputed about the Königsberg saga is that South Africa played a definitive part in a fascinating naval drama that was enacted on the stage of a comparatively little known theatre of operations at the time. It was the Royal Navy's Cape of Good Hope Squadron, based at Simon's Town, which was called upon to seek out and destroy the Königsberg. The exploits of Dennis Cutler and P J Pretorius provided the intelligence needed to assist the Royal Navy in bringing the drama to a successful conclusion. The two guns on display in South Africa today at the Union Buildings and at the Ditsong National Museum of Military History, along with a small display at the Museum which features three parts of the sighting mechanism of one of the guns, a splinter from one of its shells and part of a table top made from the timber taken from the bridge of the Königsberg, are tangible embodiments of South Africa's role in this absorbing episode of the First World War.

References

Archival Sources

Library File A.455 'Königsberg' (The archives of the Ditsong National Museum of Military History)

Published Sources

Barker, A J, 'The end of the Königsberg' in Purnell's History of the First World War, Volume 2.

Collyer, J J, The South Africans with General Smuts in German East Africa, 1916 (Pretoria, Government Printer, 1939).

Pretorius, P J, Jungle Man. The Autobiography of Maj P J Pretorius, CMG, DSO and Bar (London, George G Harrop, 1947).

Email and internet sources

E-mail correspondence with Mr R Wagner of Raubsville, Pennsylvania, USA (February, March, 2015).

Blog.nationalarchives.gov. uk/sinking_of_the_German_Cruiser_Konigsberg (accessed 8 October 2015).

www.navalofficer.com.aw/rufigi/ (accessed 8 October 2015).

s40091 0952. websitehome. co. uk/germancolonialuniforms/ militaria/koenigsberggun.htm (accessed 1 Sept 2015).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org