The South African

The South African

From a number of sources, including James Wilson's excellent Guerrillas of Tsavo, I have read that when the South African infantry attacked Salaita Hill on 12 February 1916, 15 Feldkompanie 'counterattacked'. As a former Artillery Forward Observer, I used to become quite attached to the protection offered by my trench or revetment and I found it difficult to comprehend this report. The question in my mind was: 'Why on earth would you leave your comfortable trench where you are safely firing at the enemy who is in the open and go charging about with bayonet fixed?'

The answer is in the South African Military History Society's Military History Journal, Vol 7 No 4, December 1987, 'A Machine Gunner's Odyssey Through German East Africa: The Diary of Colonel E S Thompson'. Col Thompson writes: 'Several men of "D" Company of the 7th [South African Infantry] got into the first line of trenches but as the 5th would not support them had to evacuate the place.' Now, if the trench were penetrated, that would be a very good reason for 15 Feldkompanie to counterattack.

With this information in mind, we should, of course, start at the beginning.

Background

Having made relatively 'short work' of the German controlled forces in German West Africa (now Namibia), the British Government decided to turn over the campaign in East Africa to South African command. To this end, General Jan Smuts's appointment as overall Theatre Commander was announced on 10 February 1916 and he took over physical command from General Tighe (British) on 19 February 1916 when he arrived in Mombasa. The battle for Salaita Hill, on 12 February 1916, was therefore the last significant action under overall British Command in East Africa.

The local commander was Brigadier General Wilfrid Malleson, a career soldier commissioned into the Royal Artillery in 1886. In 1904 he had transferred to the Indian Army. He was not an old African campaigner and had been reprimanded by General Tighe and other senior officers for the losses sustained in the action at Mbuyuni on 13 July 1915.

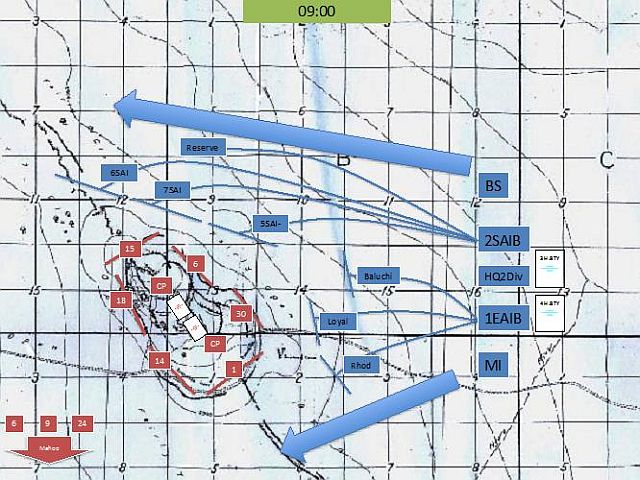

The forces of British 2nd Division available to Malleson on 12 February 1916 comprised: 1st East African Infantry Brigade ('1 EAIB'); 2nd Battalion Loyal North Lancashire Regiment; 2nd Battalion Rhodesian Regiment; 130th Baluchis; 2nd South African Infantry Brigade ('2SAIB'):5th, 6th and 7th South African Infantry Regiment ('5SAI','6SAI', and '7SAI'). Divisional Troops: Mounted Infantry Company Belfield's Scouts (mounted); 4th Indian Mountain Battery Brigade (excluding 27th Mtn Bty); 28th Mountain Battery Royal Artillery; No 1 Light Battery; Calcutta Volunteer Battery No 3 Heavy Battery; No 4 Heavy Battery; Royal Naval Air Service with four armoured cars; Volunteers Maxim Battery; and 61 Pioneer Battalion. The total force numbered about 6 000 troops, eighteen guns and 41 machine guns.

Opposing 2nd Division was the Colonial Protection Force from German East Africa (now Tanzania), the Schutztruppe. They were commanded by the charismatic Oberst Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck who had previous African experience in the (now controversial) Herero Rebellion (1904-1906). From the outbreak of war, von Lettow-Vorbeck knew that he was unlikely to receive any significant resupply and decided to employ mainly guerilla tactics to tie down as many enemy soldiers as possible, soldiers that could otherwise be committed to the fighting in France or other theatres. As he writes in his book, My Reminiscences of East Africa: 'Owing to the position of the Colony and the weakness of the existing forces ... we could only play a subsidiary part. I knew that the fate of the colonies, as of all other German possessions, would only be decided on the battlefields of Europe. To this decision every German, regardless of where he might be at the moment, must contribute his share. In the Colony also it was our duty, in case of universal war, to do all in our power for our country.'

In January 1914, the Schutztruppe had comprised only 260 German officers and NCOs along with 2 472 black African soldiers known as 'Askari'. A typical Schutztruppe company normally comprised about 20 Europeans and 175 to 200 Askari. It was trained to operate as a single unit or as part of a larger formation and was normally equipped with two machine guns and often was fortunate enough to have an attached medical officer. German officers and non-commissioned officers were well integrated into the company. The Askari were well trained and disciplined troops who had proved their valour at, amongst other places, the opposed naval landing at Tanga (I strongly recommend the book, Battle of Tanga, German East Africa, 1914 by Major Kenneth J Harvey) and Mbuyuni.

Salaita Hill commands a significant vantage point on the route Voi, Maktau, Taveta, Moshi and was not a position that 2nd Division could leave behind as they pushed forward towards German East Africa. It had to be taken.

Salaita Hill

Intelligence obtained stated that Salaita was garrisoned by around 300 'rifles' with machine guns but no artillery. Whilst this information proved to be inaccurate, British Intelligence had informed Command that there were other forces stationed within reach of Salaita in Mahoo and Taveta. (This should have come as no surprise as on the two previous occasions when Salaita was threatened by the British - 29 March 1915 and 3 February 1916 - German reserves were deployed.)

In fact, the Schutztruppe forces comprised: At Salaita, 1, 14, 15, 18 & 30 Feldkompanien and 6 Sch&uu,l;tzenkompanie, a total of about 120 Germans, 1 200 Askaris, twelve machine guns and two small field guns. Within reach at Mahoo were 6, 9 & 24 Feldkompanien, 600 strong and, in the Taveta area, 3, 10& 13 Feldkompanien, also 600 strong.

Salaita Hill is a feature running roughly north-west to south-east as can be seen from this map made by aerial reconnaissance. Malleson's plan was relatively straightforward with 1st East African Infantry Brigade advancing towards Salaita from the east, their objective being to stand off and hold the Schutztruppe's attention, while 2nd South African Infantry Brigade moved to the right flank and assaulted the position from the north. Heavy artillery was deployed in the centre and mounted troops on the flanks. (I have read that Malleson ordered a champagne breakfast in anticipation of a swift victory but have seen no evidence that this is true.)

Alea Iacta Est ('the die is cast')

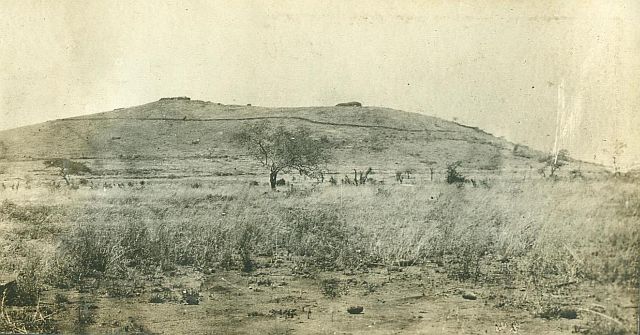

Deployment by 2nd Division was uneventful and the artillery started firing at dawn. Unfortunately the main target for the heavy guns was a visible line of trenches near the top of Salaita Hill. These trenches, seen clearly in the 1916 photograph, were unoccupied, the defenders being dug in at the base of the hill in relatively dense undergrowth. Interestingly, aerial reconnaissance had identified the upper trenches as 'dummies' but Command chose to ignore this intelligence. Aerial reconnaissance was in its infancy and there existed a tension between the Intelligence service and Command. In his memoirs, Colonel Thompson records, on 14 February 1916: 'Had an interesting talk with 2 mechanics from the S. African Aviation Corps who said that the pilot in the airplane dropped a note to the General advising him not to attack as Salaita Fort was too strongly fortified and they also asked if they could drop bombs on the German trains bringing up reinforcements but the General wouldn't let them for some reason or other .. .'

The 1st East African Infantry Brigade advanced as ordered with the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment in the vanguard, 2 Rhodesians to their left and with 130 Baluchis in reserve right flank rear. They halted short of the German positions and held.

The 2nd South African Infantry Brigade also advanced according to plan with 7SAI in the centre and with 5th and 6th left and right respectively. (5SAI was understrength, having been reduced by two companies which, along with some mountain artillery, had been formed into a Brigade reserve, again, right flank rear). German artillery started to fire on 2SAIB 'sporadically'.

By approximately 09:00, 7SAI had closed to about 800 metres from the German lines. They were under intense machine gun and rifle fire and they stalled. Fortunately, a section of mountain guns (small artillery pieces) deployed and started to pound the first line trenches, which gave 7SAI just enough support to storm the German line. 'Several men of "D" Company of the 7th got into the first line'. Thompson recalls: 'D Coy was the Anzac company with a number of Australians and New Zealanders (residents of the Transvaal), and a handful of ex-convicts on parole, who proved to be good soldiers and companions'.

Unfortunately for 2 Div, the slender occupation of the first line trenches was brought to a close by both a fierce counterattack by 15 Feldkompanie against 7SAI and the arrival of Abteilung Schultz from Mahoo with 6, 9 & 24 Feldkompanien. The Abteilung's 600 Askari, force-marched to Salaita, bayonet-charged first into 6SAI and then into 7SAI. Unnerved by the ferocity of the German defence, plagued by insects, heat, thirst, hunger and with poor communication between adjoining units in the bush, 2SAIB was thrown back. Thompson reports: 'but as the 5th would not support them [7SAI] had to evacuate the place'. His criticism continued: 'The 5th Regiment then began to retire and acted disgracefully, refusing to halt and lie down when ordered.'

The Officer Commanding the 2nd Bn Rhodesian Regiment writes in his battalion war diary: 'Men of two broken regiments streamed through our ranks, running to the rear, getting to safety and yet Rhodesians lay there, quietly shooting when targets offered, quietly enduring a shellfire that our guns had failed to silence and then failed to reply to'.

While 2SAIB were engaging from the north, 1 EAIB advanced from the east in an effort to relieve pressure but to no avail. 1 EAIB were stopped short of the trenches by a strong defence of machine guns and rifles. With 2SAIB in full retreat, the 130 Balushi deployed facing north and took on the lead elements of Abteilung Schultz. This battle-hardened Indian unit bore the brunt of the Askari fury in, at times, hand-to-hand combat and held firm. Repulsed, the Askari turned and hunted down the remnants of the retreating 6th and 7th Regiments, causing much harm.

At 13:20 a general withdrawal was ordered and the German forces harried the retreating 2 Div back to their camps.

The 2nd Division's casualties (dead, wounded and missing) were 138, of whom 83 were 7SAI. Of these, one officer and 29 men were 'missing in action'. (I have read that it was thought possible that they had deserted, but this was not the case). In von Lettow-Vorbeck's reminiscences, he states that '[w]e buried more than 60 Europeans'. He goes on to say that '[t]he training of these newly raised formations was slight. After the action of Oldorobo [the German name for Salaita], however, we observed that the enemy sought very thoroughly to make good the deficiencies in his training.'

Most of the dead from Salaita are now buried in Taveta Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery. There are 49 graves from 12 February 1916 comprising: 2 from 5SAI, 13 from 6SAI, 29 from 7SAI, 1 from the Volunteers Maxim Battery, 1 from 130 Baluchis, and 3 from the 2nd Rhodesians. This speaks to the burden that 7SAI shouldered in getting to the trenches and that 6SAI faced when attacked by Abteilung Schultz.

In conclusion

It is all too easy from our modern arm-chairs to be critical of the Salaita action and, at the time, the 2nd Division's defeat at Salaita was hushed up both in Britain and in South Africa. However, if there is any fault, it was not, in my opinion, in the resolve of 'D' Company 7SAI nor with the general rank and file of 2SAIB. They did what could reasonably have been expected of them, considering that the Brigade had not been thoroughly trained in the rigours of East African bush warfare, and that many of the young men were under fire for the first time in their lives.

At Salaita, 2SAIB failed the 'Rudyard Kipling' test: 'When it comes to slaughter, you do your work on water'. Col Thompson writes: 'We had nothing to eat all day except 3 biscuits and a cup of coffee at about 3 in the morning before we left camp.' 2SAIB had a rude awakening as to the martial qualities of their opponents and, for that matter, of their British, Rhodesian and, most importantly, Indian allies. This awakening and subsequent training probably saved many lives later in the East African campaign.

Bibliography

Harvey, Major K J, Battle of Tanga, German East Africa, 1914 (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2003).

Miller, C, The Battle for the Bundu (Macdonald & Janeis, 1974).

Thompson E S, 'A Machine Gunner's Odyssey Through German East Africa: The Diary of Colonel E S Thompson' in Military History Journal, Vol 7 No 4, December 1987.

Wilson, J, Guerrillas of Tsavo (English Press, Nairobi, 2012).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org