The South African

The South African

The hunt for Christiaan de Wet

As the year 1900 drew to a close, the Boers were badly demoralized after suffering a string of military defeats in the Anglo-Boer War. Christiaan de Wet had managed to escape capture in the Brandwater Basin where most of the Free State army had surrendered to Lieutenant-General Archibald Hunter. De Wet, with the Orange Free State President, Marthinus Steyn, had made his way over Slabbert's Nek on 15 July. Pursued by British columns, he had managed to reach Rhenosterpoort, near Vredefort, where he holed up for nearly two weeks, and then once more evaded the columns surrounding him. Crossing the Vaal River at Schoemansdrift, he intersected the Magaliesberg and entered the bushveld to the north. (This chase is referred to as the 'First De Wet Hunt'. For more details about it, see FransJohan Pretorius, The Boer Pimpernel; it is also described in Amery [ed] The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volume IV, pp 414-33, and in Maurice's official history, The War in South Africa, Volume 3, Chapters 13 and 14.)

De Wet ordered his men to make their own way back to the Free State. He himself took 246 men and managed to cross the Magaliesberg at a place to the west of Commando 200th Nek. Surrounded by British columns, de Wet had to cross where there was no path or road. A black herdsman told him that only baboons could cross there but de Wet declared that 'where a baboon can cross, we can cross' (De Wet,1902, p148). President Steyn and an escort circled around to the north of Pretoria, making for Machadodorp and a meeting with Transvaal President, Paul Kruger, then living in a railway carriage in the station. By the time Steyn arrived, Kruger had retreated to Nelspruit and was making ready to leave to board the cruiser Gelderland, sent to fetch him by the 18-year old Dutch Queen Wilhelmina. (Wilhelmina had a stern dislike of the United Kingdom partly as a result of the annexation of the republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State.)

Kruger's meeting with President Marthinus Steyn affirmed their joint resolve to fight on. Kruger was not in good health, ageing and suffering with his eyes, hence the decision that he should leave for Europe. (De Villiers, 2008, p166 gives a description of Kruger's eye disease). The Transvaal commandos had almost all dispersed. Steyn visited those who remained, 'arousing anew their enthusiasm for the cause with some stirring speeches' (Amery [ed], Volume IV, p474.) Generals Louis Botha and Ben Viljoen and State Secretary Francis Reitz were as determined as ever to fight for their independence and led their men through the bushveld in what is now the Kruger National Park to Pietersburg (now Polokwane). The Transvaal government was still functioning there and the Vierkleur, the flag of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, flew over the government buildings. Steyn followed and made fiery patriotic speeches at gatherings in a number of towns, drawing a sizeable crowd in Nylstroom (now Modimolle) (Viljoen, 1903, pp146-150. Chapter XXIV is an interesting account of this period when he describes the Transvaal Boers as 'dispirited and demoralized').

Steyn needed to return to the Free State but first wanted to meet with General Koos de la Rey at Ventersdorp and ordered De Wet to attend as well. De Wet had had little trouble making his way back to the Free State across the Krugersdorp-Potchefstroom railway line, thence to Van Vuurenskloof, across the Vaal, and back to Rhenosterpoort on 22 August. There he was joined by the commandos of Vrede and Harrismith, as well as by Generals Piet Fourie, C C Froneman and Judge Barry Hertzog. He had spent the next month reorganizing the Free State commandos.

The fight continues

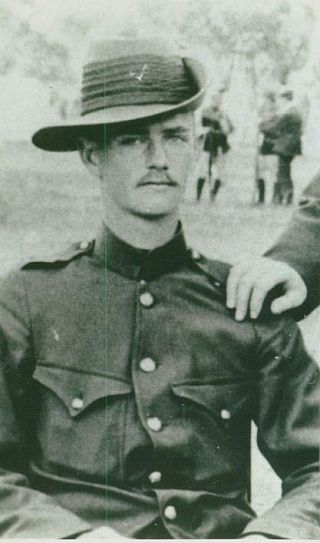

By the beginning of October there were considerable numbers of Boers back on commando in spite of their having taken the oath of allegiance that Lord Roberts had offered after the fall of Bloemfontein. It was at this time that de Wet went to Potchefstroom which was as yet unoccupied by the British. The Boers were busily engaged in refurbishing rifies taken from the pile of surrendered weapons which was burned by the British on their way through to Pretoria in May 1900. De Wet had his photo taken with the 200th repaired weapon. (De Wet, p153 gives the full story of this enterprise. See also the famous picture of de Wet holding the 200th refurbished rifle.)

Frederickstad

In mid-October De Wet responded to a request from General P J Liebenberg to join forces and attack the column of General Geoffrey Barton, encamped at Frederikstad Station. Frederikstad, said De Wet, 'was a miserable affair altogether' and, on 25 October, he and his men headed for Van Vuuren's Kloof on the north bank of the Vaal River, the hills which form the rim of the Vredefort Dome. (The Vaal River flows through a spectacular series of hills in this area, formed when a giant meteorite collided with the earth about 2 billion years ago. Truswell (1977) describes this geology). They needed to cross the river but many of the drifts were guarded.

While the battle at Frederikstad was taking place, Lord Roberts issued orders to Colonel Charles Knox to assemble a relief force. At the time, 21 October, Knox was at Heilbron, moving to Witkopjes on 23 October to combine with Lieutenant-Colonel Henry de Lisle's column with the Colonial Division under Colonel John Maxwell. On 25 October, Colonel Philip le Gallais arrived from Bothaville to join the force at Reitzburg (Childers, The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol V p13.)

No longer needed to relieve Major General Geoffrey Barton at Frederikstad, Knox's objective was now to find de Wet's force and deal with it. His force was all mounted and with four guns of 'U' Battery Royal Horse Artillery. (Knox's force consisted of the 600-strong Colonial Division, de Lisle's column of Australians and Ie Gallais's 5th, 7th, 8th Mounted Infantry, Imperial Yeomanry, Royal Horse Artillery, and Australians.) This predominantly mounted force almost matched the mobility of their Boer adversaries, in contrast to 'the ponderous columns of infantry' (Childers, Times History, Vol V, p13) which had been fruitlessly chasing their elusive foe on foot. Nevertheless it had taken some time to concentrate at Reitzburg, still at least a few days' march from Frederikstad, twelve miles (18 km) north of Potchefstroom.

Leaving Le Gallais at Tygerfontein so as to block de Wet's possible escape route over the Vaal River at Schoeman's Drift, Knox occupied Potchefstroom on 26 October. There he learnt that De Wet was indeed not far away. His information was that De Wet was headed to Lindeque's Drift. The Boers, who had found their way barred by Le Gallais at Tygerfontein, had been forced to double back, and continue upstream looking for a crossing place. Le Gallais was ordered to cross tne Vaal at Venterskroon and work towards Vredefort with a view to intercepting the Boers if they attempted to cross the Vaal. (Childers, Times History, Vol V, p14)

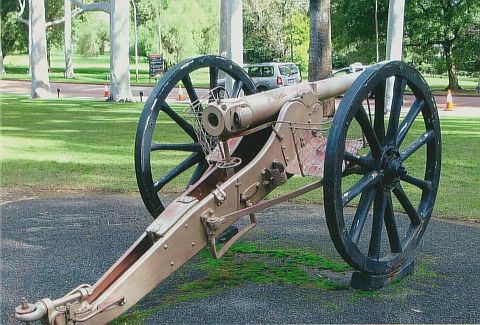

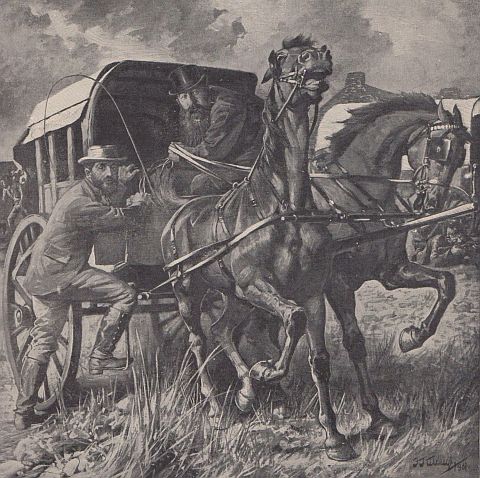

On 26 October the Boers spent the day travelling upstream and sometime after midday they reached Rensburg Drift. This was not really a recognized crossing place but a place where the Vaal splits up into a number of streams and small islands. Early the following morning, they crossed and off-saddled. In spite of their chiefs strictures that wagons and carts should not accompany the commandos, they had some horse-drawn carts with them, but in addition, they had four artillery, three 75mm Krupps, two captured British guns and two machine guns. It would have taken some time to get all the guns and transport across (De Wet, 1902, p168).

On the same day, the men of de Lisle's column set off in pursuit of the Boers. At 08.00 they came upon the site of the Boer laager of the previous night, 'with the fires hardly yet cold' according to Lieutenant Livingstone-Learmonth of the 1st New South Wales Mounted Rifles. This must have been some distance away from the Vaal River and in the Van Vuuren's Kloof hills (Chamberlain & Drooglever, The War with Johnny Boer p346. Letter from Lieutenant Livingstone-Learmonth of the 1st New South Wales Mounted Rifles.) Learmonth describes how they passed over open rolling country before the road 'closed in to a high narrow valley which led for ten or twelve miles to the Vaal'. Here they were held up for a short while by a few Boers at a small koppie, who opened fire. This was an area of thick thorn bush and, in scattering to return fire, the Australians discovered an abandoned 12-pounder Krupp gun, minus the breech-block of course - clearly they were close to overtaking the Boers. (Lord Roberts subsequently 'had much pleasure in acceding to the request of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles' to take their captured guns back to Australia and hoping that they would capture many others.)

Learmonth says that they reached the Vaal at about 16.00 and sighted the whole Boer army, which had just crossed the drift. The advanced scouts of the 1 NSWMR passed the word for the main body to come up at a gallop. A pom pom under Captain Stirling and two guns of 'R' Battery RHA under Captain Lamont opened fire and 'the Boers numbering about a thousand, scampered off in every direction'. Colonel Henry de Lisle passed the word that 'the drift must be crossed at all hazards' (Chamberlain and Drooglever, The War with Johnny Boer, p346. Letter from Lieutenant Livingstone-Learmonth of the 1st NSWMR) and away soon 'we had two streams of men crossing the Vaal and the enemy in frantic retreat in front of them' (Chamberlain and Drooglever, The War with Johnny Boer, p345. Letter from Captain W Watson of 1 NSWMR). The Boers seemed to be making for Witkopjes (Wittekoppies) but were seen to turn east, making off in the direction of Parys.

Le Gallais, coming up from Vredefort was also in pursuit, this being the reason for the Boers retiring to the east rather than south towards Vredefort. From Schoemans Drift Le Gallais had moved north along the right bank of the Vaal River, but was able to cross at Venterskroon where there are the remnants of a disused drift. This brought his column in contact with the Boers retiring from Rensburg Drift. Just at sunset Le Gallais's pom pom put a shell into a Boer wagon which was carrying ammunition. There was a huge flash as it exploded. There they found the 'mangled remains of a couple of Boers, half a head and trunk here. A leg there and so on'. (There is a small monument marking the spot where the wagon exploded - it is in the veld to the south of Parys and difficult to find). The Times History says that De Wet lost two guns, eight wagons and 24 killed, wounded and captured, one of whom was Lieutenant Wessels of Theron's Scouts. Lieutenant Learmonth says:'It was better than a good fox hunt. They (the Boers) were "fairly on the run, every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost - wagons were dotted about and pack mules cast off every here and there. By now it was absolutely dark and the rain came down in torrents.''' (Chamberlain and Drooglever, 2003, p 346: Letters from Captain W Watson and Lieutenant Livingstone-Learmonth, both of the 1st Battalion, New South Wales Mounted Rifles).

When darkness fell, the Boers altered direction, made off to the south-west, and the British completely lost the scent, partly because the rain may have erased some of the tracks. Knox and his men camped at Groote Eiland for the night, without wagons, blankets and food, all the transport only making it across the river late on 28 October, although sufficient supplies had arrived to give the men breakfast that morning. Also, Knox did not order an immediate pursuit, which certainly helped his quarry to get clean away.

De Wet, in his book, Three Years' War, has quite a different account, telling of how they were attacked by the British 'just as we had partaken about noon of a late breakfast'. He writes (p168) that they crossed at 'Witbanksfontein' on the morning of 26 October. (Here, he was probably referring to Witklipfontein, just a short distance upstream of Schoeman's Drift). There is a long reach in the Vaal River here which was wide and quite shallow - nowadays much deeper because of the weir at the drift. (De Wet may have had a lapse of memory, writing his book without notes while on board ship to England with Generals Botha and de la Rey in 1903). The Boers headed south-west and spent that night 'at Bronkhorstfontein near the Witkopjes' (De Wet, 1903, p168). (This place is difficult to pinpoint on modern maps - possibly the farm has been renamed). On the night of 28 October, they were at Winkelsdrift, on the Rhenoster River.

Bothaville

At Winkelsdrift, de Wet received the message that President Steyn was returning from his visit to President Kruger and wished to meet with him. De Wet left the commandos under the command of Commandant C C Froneman with instructions to 'go in the direction of Bothaville' and went with a small escort to Ventersdorp in the Transvaal to meet with Steyn. Although the British were not to know, Steyn and De Wet decided that an attempt was to be made to invade the Cape Colony. De Wet's meeting with Steyn was on 31 October and, by 5 November he and the President were back with the commandos near Bothaville. (According to de Wet [1903, p169], General Koos de la Rey was also supposed to be at the meeting but 'was prevented from coming').

After the clash at Rensburg Drift, Knox decided to sweep westwards on a broad front, making use of the main railway line. He spread out his force - the Colonial Division camping at Grootvlei, some distance south of present-day Sasolburg; De Lisle's men at Koppies, then just a station; and Le Gallais at Honingspruit. Knox himself and his staff were with De Lisle. Some false intelligence caused Knox to send the Colonial Division north towards the Vaal River so they were not involved in the drive westwards towards Bothaville.

Le Gallais knew well that Bothaville had been destroyed a few weeks before - he and his men had been part of a force under Lieutenant-General Archibald Hunter which had passed through the area early in August. (Childers, The Times History, Vol V p15.) Nearing the town his men came under fire from Boer artillery across the Valsch River. This was late on the afternoon of 5 November. Two Australian soldiers, Troopers Albert Page and D R Fisher of the 4th South Australian Imperial Bushmen describe how the Boers opened fire with a pom-pom and a 15-pounder. Another man, Trooper Tom Stott, said 'not much damage was done on either side', but Fisher wrote that '...shells were flying in all directions. There was a house a little distance off. I got behind it with four or five others when the enemy put a pom-pom onto us. That gun threw a pound shell, and could fire 25 shells without stopping. They put about a dozen into the house where we were and blew one side down. Stones were flying in all directions. I thought it was all "up a tree" with me. Some of the horses pulled away, but I managed to get mine and he followed me for about a mile. I was well out of the road then. Our big guns next came up and fired a few shots. It then got dark and the enemy cleared. They thought we wouldn't follow them, but we did.' (Letters from Troopers Tom Stott and D R Fisher, Fisher's appearing in The Advertiser, Adelaide, 28 December 1900.)

The Boer camp at Doornkraal

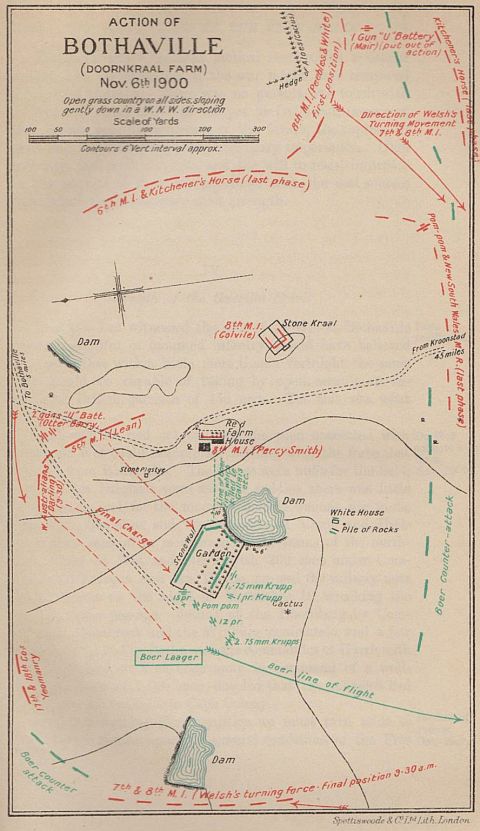

Le Gallais and his men camped that night in the town square and ascertained that De Wet and Froneman had arrived in the course of the day - presumably from some local black people. Commandant Steenekamp with the baggage and artillery had also passed through. The Boers were camped at Doornkraal, a short distance south of Bothaville in a slight depression. (Today, the site of the battle is alongside R59 road and adjacent to the monument at the roadside. The layout is clear from reference to the battle map.) According to the Times History of the War in South Africa (Vol V, p 16), '[a]fter his skirmish with Le Gallais ... De Wet outspanned at Doornkraal farm, about five miles [8 km] from the river, keeping the Valsch River between himself and the British troops'. The Boers had surely been there some days however, as camping in the ruins of Bothaville would have been distasteful. Major-General Knox was with De Lisle's men at Elandsvley, about 10 km north-east of the town.

The battle

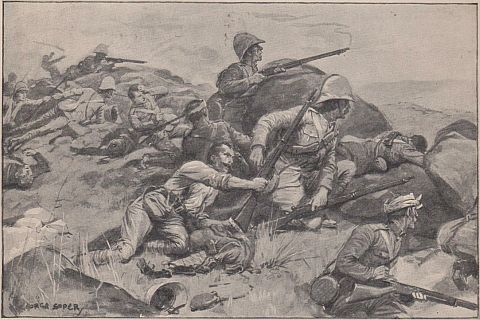

Le Gallais's men crossed the Valsch at 04.00 and almost immediately came upon a Boer picket of five men who were all asleep. Major Kenneth Lean and the 8th MI were in the lead and the Boers were captured without a shot being fired. The spoor of the Boer guns was also clear and the advance continued. Lean knew that the Boer laager was nearby and sent back for the guns. Three guns from 'u' Battery joined them and Lean and 67 men galloped forward to a rise from where they could see the Boer laager not 300 metres distant. The men were asleep, the guns and wagons outspanned and the horses grazing loose. By then it was about 05.30. Lean's men lined the crest of the rise and opened rapid magazine fire on the laager. (For more detailed descriptions of the battle that ensued, see The Times History, Vol V, pp16-21 and Maurice, Vol IV, pp 486-9).

Completely surprised, most of the Boers grabbed whatever horses they could find and galloped away, De Wet and Steyn included. De Wet said of his men that 'a panic had seized them'. Seeing De Wet himself saddling his horse and leaving the scene cannot have induced his men to make a stand and defend their position. Many of the Boers had even galloped away bare-back and De Wet's efforts to rally the men were unavailing (De Wet, 1903, pp 171-2).

Major Lean and his 5th MI spread out with the Worcester company in the centre, the Royal Irish holding a kraal on the left and the Buffs on the right, by now having advanced to a position on the edge of the Boer laager. The 8th MI reinforced the 5th, occupying a farmhouse and kraal on the left.

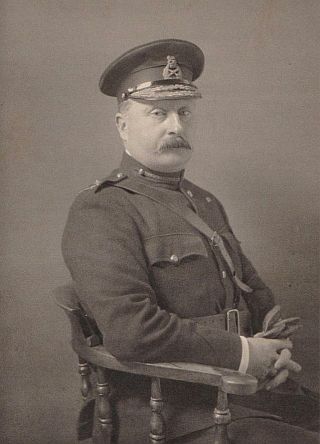

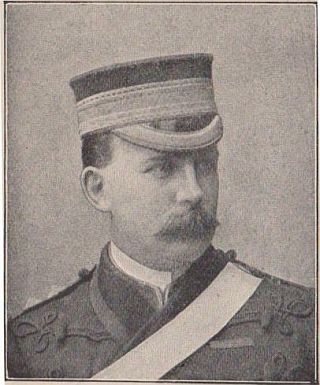

About 130 Boers occupied a garden with a substantial stone wall and fought bravely to save the guns which they were unable to bring into action, being showered with shrapnel and case by the guns of 'U' Battery. The bank of a small dam was also occupied by the Boers who were in a strong position for defence. Colonel le Gallais was soon on the scene and he and second-in-command Lieutenant-Colonel Ross took up position in the farmhouse. As the door of the farmhouse was open, anyone moving around was clearly visible to the Boers only 100 metres away. Le Gallais was mortally wounded and Ross severely wounded. A number of officers were killed and the 170 British soldiers were in a critical situation. Le Gallais had sent his staff officer, Major William Hickie, to order every available man to the scene. It was an hour before reinforcements arrived. Knox left his camp at 05.00 and soon heard Le Gallais's guns in action. (Pakenham, 1979, pp 475-6 quotes Hickie as referring to the General as 'an old woman', based on the fact that it was 08.00 before de Lisle's reinforcements arrived.)

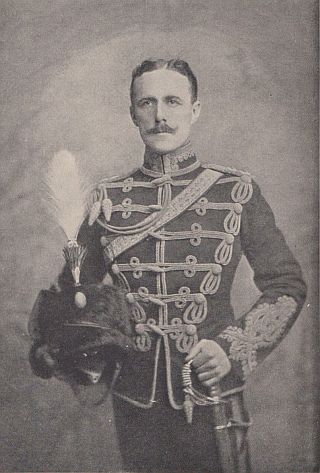

When de Lisle arrived with further reinforcements at about 10.00, he took command. The Boers, whom de Wet had managed to rally and were trying to counterattack, were driven back. De Lisle sent his New South Wales men to the left, where they fired on the garden and the Boers in the small farmhouse to the rear. Late reinforcements were some West Australians under Lieutenant Darling. The garden was surrounded, the counterattack beaten back, and de Lisle determined on decisive action. Thus, the 5th MI and Darling's West Australians were ordered to fix bayonets and charge. With the first flash of steel, the white flag went up and the Boers surrendered. (De Beauvoir de Lisle, 1939, pp 112-13). De Lisle also describes how Colonel Walter Ross was wounded by a bullet that hit him on the point of the chin. An operation was performed without chloroform in Kroonstad to remove his lower jaw! He lived on soup and milk for some time but later found he could eat mince. He commanded a brigade in the First World War as Brigadier-General Sir Walter Ross.

The aftermath

De Wet and Steyn were now in rapid flight and the guns and supplies which they had been accumulating over the last two months were all lost. De Wet claimed (1903, p 171) that the loss of the guns made little difference to them 'as our ammunition for these pieces was nearly exhausted'. For the guerrilla warfare now beginning, such hardware would indeed have been of doubtful advantage to them anyway. Wagons and supplies would have been a more significant loss but the Boer casualties were considerable.

For the British, the loss of ten officers was serious, none more so than the loss of Philip le Gallais, an officer of proven ability in countering guerrilla tactics. The British pursued their beaten enemies but 'found that the enemy had broken up into small parties and dispersed all over the district' (Maurice, Vol IV, p489). The Times History's comment (Vol V, p21) was that '[i]t was yet to be learnt that the capture of guns and supplies was of very secondary importance' in the guerrilla war which was now gathering momentum. Had they succeeded In capturing De Wet and President Marthinus Steyn during the ambush at Doornkraal, this would surely have had a significant effect on the progress of the war. But the two men had escaped, and what is truly remarkable is that little more than a fortnight later, De Wet had assembled another force. With 1 500 men and a Krupp gun, he remained a thorn in the side of the British, overcoming an entrenched British garrison, 450 strong, and capturing the town of Dewetsdorp in the southern Free State as he made his way to invade the Cape Colony.

The Boer memorial in the national graveyard

across the road from the battle site.

Bibliography.

Amery, L S, and Childers, E, The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vols IV and V (Sampson Low, Marston and Co, Ltd, London, 1906/7).

De Beauvoir de Lisle, Henry, Reminiscences of Sport and War (Eyre & Spottiswoode, London, 1939).

De Villiers, Dr J C (Kay), Healers, Helpers and Hospitals, Volume II (Protea Bookhouse, Pretoria 2008).

De Wet, Christiaan, Three Years' War (English edition, Archibald Constable & Co, 1902 [reprint Galago Publishing, Alberton, 1986]).

Maurice, J F, Sir, History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902 (Hurst & Blackett, London, 1906-8).

Chamberlain, Max and Drooglever, The War with Johnny Boer: Australians in the Boer War 1899-1902 (Australian Military History Publications, Loftus, Australia, 2003).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War (Weidenfeld & Nicholson Ltd, London 1979).

Pretorius, Fransjohan, The Great Escape of the Boer Pimpernel (University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2001).

Truswell, J F, The Geological Evolution of South Africa (1977).

Viljoen, Gen Ben, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War (Hood, Douglas & Howard, London, 1903 [reprint C Struik (pty) Ltd, Cape Town, 1973]).

Wallace, R L, The Australians at the Boer War (The Australian War Memorial and the Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1976).

Wilcox, Craig, Australia's Boer War (Oxford University Press, 2002, published in association with the Australian War Memorial).

Wilson, H W, After Pretoria, Volume I (published in parts, London, 1900-02).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org