The South African

The South African

This is the third and final article relating to the small farm at Rietfontein, six miles (9.6 km) outside Ladysmith on the Newcastle road. The first article, which was about the battle of Rietfontein, appeared in two parts in the June and December 2012 editions of the Military History Journal, Volume 15 Nos 5 and 6 respectively. The second article, 'The Boer Hospital at Rietfontein', covers the period of the siege and the importance of Rietfontein hospital as the main field hospital for the entire besieging force and appeared in the June 2014 edition, Military History Journal Volume 16 No 4. This latest article is designed to put the record straight regarding the Boer rail terminus at Rietfontein, referred to by the Boers as 'Modderspruit'. The assumption is that the Boers took over an existing station and converted it for their use; in fact, they built the station from scratch and used it as the primary logistics supply route throughout the period of the occupation.

Introduction

In 1899, having driven the British from the field four times in ten days, Talana (20 October), Elandslaagte (21 October), Rietfontein (24 October) and Lombard's Kop (30 October), the Boer army decided to lay siege to Ladysmith, an event that would be closely followed in Britain and around the world. The siege was not part of the original Boer strategy in Natal, to use overwhelming force to drive the British to the sea at Durban and then hope that a friendly European power might intervene, but it certainly brought the region into the spotlight.

Great Britain was essentially a naval power rather than a military one. She maintained a small, highly trained army garrisoned around the Empire, which could be hastily transported to trouble spots as and when required. This had been the tried and trusted situation for the last 300 years. By the second half of the nineteenth century, British naval strategy was based on the 'two-power standard', whereby the Royal Navy would be maintained with the number of capital ships (battleships and battle cruisers) in excess of the combined strengths of the next two largest navies, namely those of France and Russia. Germany, in 1899, had no navy of which to speak, but was a formidable military power. Neither France, nor Russia, either singularly or collectively, seemed inclined to engage Britain in support of the Boers. If this were not enough, as much as 60% of the world's merchant marine was British owned and registered.

A siege is the name given to a particular mode of attacking a town or city which cannot be taken by direct attack and is a common military strategy to starve the enemy into submission. The naval equivalent is called a blockade. A siege, if successful, can be decisive. The Franco-Prussian War was brought to an end by the Siege of Paris in 1870-71. Victory is not guaranteed, however. For example, the Siege of Leningrad, between 1941 and 1944, and the Siege of Sevastapol in 1943, both failed. The most decisive factor in determining the success or failure of a siege seems to be the morale of the besieged, when measured against the resources of the besiegers. At Ladysmith, Boer control of the railways that flowed into the town no doubt had some effect on the decision to besiege it.

Overview of the railways in the Anglo-Boer War

The strategic use of railways in wartime has its roots in the nineteenth century. Having pioneered the new technology with the opening of the Manchester-to-Liverpool railway in 1829, railways were used extensively in the Crimean War of 1853-55, the American Civil War of 1861-65 and the already mentioned Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. In both the American and Franco-Prussian wars, it was found that control of the war depended on control of the railways. Why should this be? The railways were a speedy, economical and an efficient means of transporting large quantities of men, horses and materials to the decisive point in the war, and the inability of one side to make use of this facility left them at a serious disadvantage. During the Anglo-Boer War, there were two railway authorities that linked Ladysmith to Pretoria. In Natal, the Natal Government Railway, or NGR, ran the railways. Across the border, the NZASM (or Nederlandsche - Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg Maatschappij, or Netherlands - South African Railway Company) controlled the railways in the Transvaal Republic.

At the start of the siege, the Boers seized control of the NGR from the Natal border with the Transvaal and Free State republics to the siege line at Ladysmith and at Intombi, where the line continues on to Durban. The lines were cut at Rietfontein and at Potgieter's Farm, four miles (6.4 km) out on the Harrismith road. Obviously, no Boer transport was coming up the line from Durban and the line down from Van Reenen's Pass was very cumbersome, by virtue of the steep elevation, which meant that trains zigzagged down the mountain in a manner of going slowly down the gradient in a switch-back motion, first forward, then in reverse. More significantly, this line only reached Harrismith. There were no such impediments on the line to the Transvaal.

The Boer railway terminus at Rietfontein

We have already seen that the Boers established their main field hospital at Modderspruit (Rietfontein) and also their Hoofdlaager (main camp). Therefore, it was hardly surprising that Rietfontein was also chosen as the site of the rail terminus.

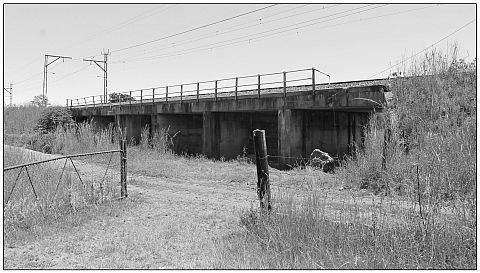

A note on the term 'Modderspruit': This requires clarification, as there are various unrelated references to Modderspruit during the Anglo-Boer War. Firstly, Modderspruit refers to a series of tributaries that run down from hills around Rietfontein and pass under the railway via a system of culverts; Modderspruit Bridge is a three span bridge, crossing the largest tributary at Point 199 ¾ (see Photo 8 below); Modderspruit Siding (where Generals White and French chose to muster and deploy their force prior to the battle of Elandsfontein) was a series of sidings, numbers unknown, located beyond the bridge, where trains could be stored, assembled, watered and maintained, which was not possible in the confines of Ladysmith Station; although both Amery and Maurice erroneously show it on their Rietfontein battle maps; Modderspruit Station was actually built later, during the Boer occupation of the farm; Modderspruit Farm was the name given to Rietfontein by the Boers and was also known as Pepworth's or Reid's Farm after the co-occupiers; the Battle of Modderspruit was the Boer name for the battle of Lombard's Kop; Modderspruit Cemetery, not to be confused with the cemetery at Rietfontein, lies across the Newcastle Road, a mile above the station.

The Natal Government Railway (NGR)

The first railway in Natal was incorporated in 1859 and known as the Natal Railway Company (NRC), which built and operated a two mile system between the Point and Durban town proper, basically bringing the goods unloaded in the harbour to the place of distribution (Campbell, 1951, P 11). For a good deal of its early history, the NRC relied almost exclusively on imports of locomotives, carriages, wagons, rails and so on, from Great Britain, which, of course, having pioneered the technology, now began to capitalize on its exports all over the Empire and the world. In 1875, '[u]nder Act No 4 of 1875, authority was granted for the building of a railway from Durban to Pietermaritzburg with a branch line to Isipingo and another from Umgeni to Verulam' (Campbell, 1951, P 43). This is essentially the expansion north, south and north-west, the latter being of interest here. What was also important about the Act of 1875 was that in future it would be the colonial government rather than private enterprise that would give direction to the railway's future, although much of the capital was rallied by the public as well as government subscription. The future railway was henceforth given the title of the Natal Government Railway (NGR).

The route was divided into three districts. District 1 was Durban to Pinetown, a distance of 17 miles (27.3 km) with a rise above sea level to 1 125 feet (343 m). District 2 was Pinetown to Inchanga, a distance of 22 miles (35.3 km) and a rise to 2 064 feet (629 m) above sea level. District 3 was from Inchanga to Pietermaritzburg, a further 32 miles (51.5 km) and 2 218 feet (676 m) above sea level, bringing it to a total of 71 miles (114.2 km) (Campbell, 1951, P 54). The first section was completed in June 1878 and the second and third sections in 1880, although the telegraph system was already in existence, passing through all the major towns up to Richmond. Trains departed Durban four times a day, at 09.15, 12.20, 14.20, and 17.15, all except the 12.20 train terminating in Pinetown. It is interesting how a railway system standardizes time in towns and villages, which had previously set their own time depending on the rising and the setting of the sun. Henceforth, 'railway time' was specified by the NGR, as authorized by the Colonial government.

The NGR had played a significant part in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and, with the coming of the peace, the line now known as the Main Line (as opposed to the North Coast Line and the South Coast Line), reached Howick in 1884, Estcourt in 1885, Ladysmith in 1886 and Rietfontein around 1887. Initially, the NGR had followed the standard gauge system of 4 feet, 8½ inches, a gauge originating from the distance between the wheels of a war chariot during the time of the Roman Empire. Soon, however, it opted for a more economical narrow gauge of 3 feet, 6 inches, more suitable for lines with steep gradients and sharp curves.

'It was in 1888 that Natal got her first tender engine. It was called the Havelock after Sir Arthur E Havelock, Governor of Natal from 1886 to 1889. This locomotive was bluilt in the Durban Railway Workshop, to the design of Mr W Milne, the locomotive superintendant, and was a 2-8-2 side-tank engine with four wheeled tender. To Havelock belongs the distinction of being the first locomotive and tender to be designed and built in South Africa. The engine and tender in full working order weighed fifty tons' (Campbell, 1951, P 120).

Armoured trains

With the outbreak of war, the Havelock was armoured by welding armour plate to protect the boiler and tender. The cab was enclosed and plated with a small, arched access point for the driver and the fireman. In addition to the locomotive and tender, NGR trucks were modified. These were mainly for the high-sided wagons capable of carrying 33 tons under peace-time conditions. The dimensions of the wagon were increased by the addition of 3 feet (914mm) high armour plate sides with slots cut out to enable riflemen to fire out. There were approximately 24 slots cut on each side in a staggered fashion and five slots at the front and rear, giving a total of 58 firing positions. Configurations could vary according to circumstances, but, generally speaking, the locomotive formed the centre of the train with either one or two armoured wagons in the front and rear. Additional rolling stock could be added, such as a guard's van or a wagon with platelayer tools, depending on needs on each occasion. There is no agreement as to how many of these trains were available. According to Darrell Hall, there was one armoured train, but The Times History of the War (p 109) records that two armoured trains were constructed. Girouard (1903, p 65) correctly gives the figure of five: Two of which were shut up in Ladysmith, the remainder at the railhead' (or down the line to Durban).

Construction

Before the war, the railway was typically measured in miles and fractions of miles as a distance from Durban Main Station, designated '0'. Thus, Pinetown was '17', Pietermaritzburg '71', Nottingham Road '112' and so on. This system applied not only to the stations, but every bridge, viaduct, crossing and culvert en route. Ladysmith was designated '190' and Elandslaagte, '206'. Rietfontein, had it existed then, would have been '196', ie 196 miles from Durban Main Station.

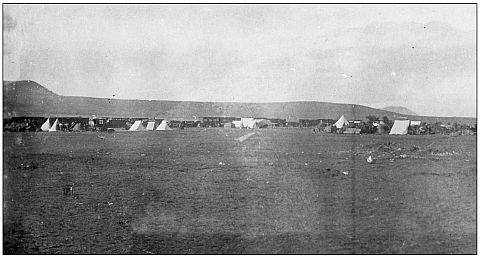

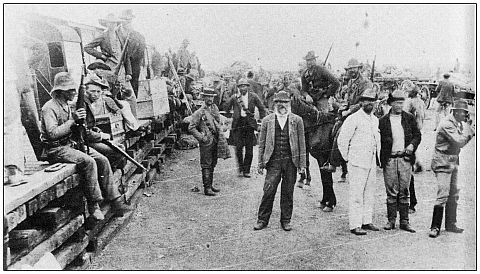

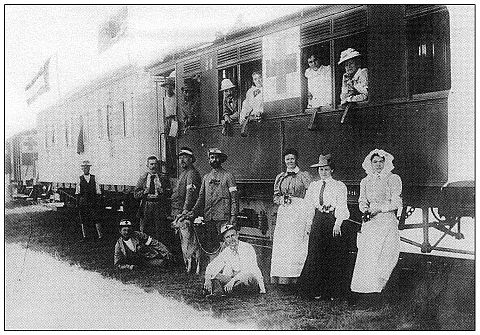

With their decision to lay siege to Ladysmith in 1899, it became incumbent on the Boers to establish a supply system in support of the siege. Rietfontein Farm lay just outside the range of the British artillery in Ladysmith, with the main camp and field hospital nearby and Modderspruit Siding, which would become a marshalling yard, only 3 miles (4.8 km) up the line. To establish the line to support the besiegers, the railway was cut at Intombi, Potgieter's Farm on the Harrismith Road, and at Rietfontein, by lifting the rails and sleepers. However, in his History of the Railways during the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Lt Col E PC Girouard (p117) points out that between mile points 184 to 185 (ie at Intombi) and 192 to 194 (the line adjacent to Rietfontein), the line was pulled up for a quarter of a mile (400m). Taking up this length of line suggests only one thing, namely that the sleepers were to be used to build platforms. This is supported by evidence in four photographs: The first (see Photo 1) shows the railhead with both passenger and freight wagons standing sedately on the track. To the left, an ambulance wagon can be clearly seen close to the carriages with an assortment of tents, wagons and stores dotted around. Photo 2, published in 1999 by Fransjohan Pretorius, shows a rudimentary platform made of railway sleepers. Photo 5 comes from Chris Schoeman's Hollander in the Anglo-Boer War (2011, photographic section) and shows an ambulance train manned by Dutch ambulance staff at Modderspruit.

Construction of a station at Rietfontein is further strengthened by the report of an eye-witness, who describes the erection of a warehouse at Modderspruit (Pretorius, 1999, p29): 'To the Dutch volunteer Cornelis Plokhooy the war commissariat at Modderspruit was an impressive spectacle. He described large quantities of foodstuffs and clothing piled up chaotically. No-one who had not witnessed it, he maintained, could imagine the outstanding volume. And then the rush, we went on - it was beyond all hearing and sight. Scores of carts drawn by hundreds of mules, as well as ox wagons each with a team of eight or sixteen oxen, stood awaiting their loads which they had to cart to the various field cornetcies. Blacks shouted and clamoured; whites strode angrily to and fro, every now and then addressing "a lovely rebuke" to a black person. The place was teeming. Nobody had an eye for anything but his own wagon and supplies. Nor was this entirely warranted, since there was any number of shady characters around who thought nothing of pilfering the odd item.'

'Theft of supplies from sheds and trains bound for Elandslaagte occurred on a large scale. From the end of October 1899 onwards the secretary of the Head Committee repeatedly notified the directors of the NZASM of shortfalls in consignments to the front. Expropriated items were mainly salt, coffee, sugar, flour, soap, matches, paraffin, oats and clothing'. (Plokhooy, 1903).

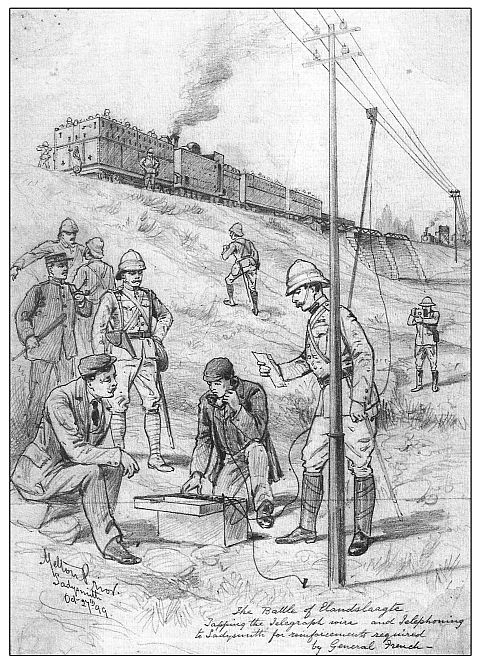

Photo 7, an illustration by the war artist, Melton Prior, shows an interesting perspective. The bridge in the background is that at Modderspruit Siding, which transverses the Modderspruit stream on the north side of the railway. Above is an armoured train with reinforced Havelock engine and armoured wagons and, in the foreground, Mr J Chorley Burton with his 'instrument', latter to be present at the Battle of Rietfontein as recorded in his diary.

The Boer retreat

After the siege, all manner of men, materials and equipment left through the railhead. The patients from the hospital were bundled on the hospital trains and taken to safety. Watkins-Pitchford, the Chief Veterinary Surgeon for the Colonial forces, also present at the battle, recalls (1964, p 123): '[n]ext morning (28 February 1899) Thursday, a column was sent out in pursuit of the retiring enemy, who was reported as having got all his guns as far as the railway terminus at Pepworth Station'.

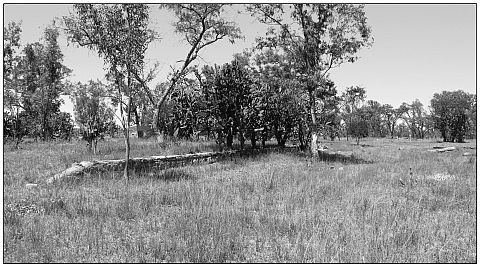

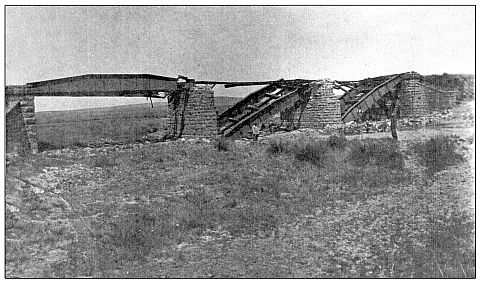

As the Boers retreated, they laid waste to every bridge, tunnel and culvert from Rietfontein to Charlestown, a full account of which is available in Girouard, who was responsible for their repair as Director of Railways, South Africa Field Force. This was not wanton vandalism; instead, it was the desperate measures taken by an army in retreat, much as Sherman did in the American Civil War during his march from Atlanta to the sea, to deny the Confederacy its railway, and the German Army did during its withdrawal from Russia in the winter of 1943-44. Photo 8 shows the damage done to the bridge at Modderspruit Siding, later to be repaired by Girouard and his engineers. It seems what was left of the terminus at Rietfontein was immediately co-opted into the existing system once repairs were complete, as explained by Harrison in his post war travel guide (1903, p 120): 'Modderspruit Station, which was left us as a legacy by the enemy on their hurried departure, gives the site of the Hoofd Laager, Joubert's main encampment during the Siege. Rietfontein and Farquhar's farms, the scenes of the engagements on 24 and 30 October 1899, are within a few miles radius of this station, while Tinta Inyoni and Pepworth's Hill, the enemy's respective positions on those occasions, can be seen.'

In 1905, the NGR purchased the land adjacent to the tracks on which the terminus had been built and changed the name from Modderspruit to Pepworth, after the owner of Rietfontein, Mr Walter Pepworth MLA.

Bibliography

Amery, L S (Ed) The Times History of the War in South Africa, 7 Volumes (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co Ltd, 1906).

Campbell, D C The Birth and Development of the Natal Railway (Shuter and Shooter, 1951).

Girouard, E P C History of the Railways during the War in South Africa 1899-1902 (HMSO, 1903).

Harrison, C W F Natal. An Illustrated Official Railway Guide and Handbook of General Information (London: 1903).

Maurice, F M Sir, Official History of the War in South Africa, 4 Volumes (London: 1906).

Plokhooy, C Met den Mauser (1902).

Pretorius, F Life on Commando during the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 (Cape Town, 1999).

Schoeman, C Hollander in the Anglo-Boer War (Cape Town, 2011).

Watkins-Pitchford, H Besieged in Ladysmith (Shuter and Shooter, 1964).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org