The South African

The South African

The Battle of Salaita Hill, fought on 12 February 1916, was the first major action involving South African forces in East Africa during the First World War (1914-1918). The battle was a disaster for South Africa. The 2nd South African Infantry Brigade suffered a major reverse and received a sharp lesson in the intricacies of bush warfare from an experienced and determined enemy. To South Africans of the First World War generation, 'Salaita' was as ominous as 'Tobruk' would become to the Second World War generation (Martin, Vol 1 , 1969, 209).

Research on the 7th South African Infantry Regiment, which was formed for service in East Africa during the First World War, naturally drew the writer to experience the battle through the personal accounts of three men of the battalion who were present at Salaita Hill. These three men were a correspondent (name unfortunately unknown) of the contemporary monthly publication, Nongqai, who had been a serving member of the South African Police prior to the war; Private Robert Head of No 7 Platoon, 'B' Company, who donated to the Ditsong National Museum of Military History his diaries and a detailed typed manuscript of what he termed his 'wanderings' in East Africa during the war; and Private (later Colonel) Eric Thompson, a machine-gunner whose diaries were published in two parts entitled 'A Machine-Gunner's Odyssey' in the December 1987 and June 1988 issues of the Military History Journal.

In recent years, the voice of the ordinary soldier, sailor or airman has become an increasingly important and recognised source of information in the study of military history. Often these servicemen, whose testimony is based on their own experiences in warfare at first hand, reveal quite different perspectives about a particular event from those of their commanders and the politicians. Unfortunately, for many, this shift in focus has come too late, at a time when there are no veterans left who fought in the First World War; therefore, the first-hand accounts written by these eye-witnesses have become a critical source of the ordinary participant's perspective.

The 7th South African Infantry Regiment

An imperial service battalion recruited mainly from the former Transvaal province and formed for service in East Africa for the duration of the war, 7th SAI was part of the 2nd South African Infantry Brigade, which also comprised 5th SAI (recruited mainly from the Cape Province), 6th SAI (recruited mainly from Natal and the Orange Free State), and 8th SAI (recruited mainly from the South African Railways and Harbours in the Transvaal).

The Officer Commanding 7th SAI was Lt Col J C Freeth, who had previously seen service with the 12th Infantry (Pretoria Regiment). Included in 'A' Company were a large contingent of men from the 11th Infantry (Rand Light Infantry) and some men of the 8th Infantry (Transvaal Scottish). 'B' Company was the popular 'Sportsman's Company'. Recruitment to this company was so active that that the overflow of volunteers later formed the basis of the 9th South African Infantry Regiment. 'C' Company was made up largely of members of the 10th Infantry (Witwatersrand Rifles), while 'D' Company, nicknamed the 'ANZAC Company', was formed from the large number of Australian and New Zealanders who were resident in the Transvaal at the time (DNMMH File A.412[68], Curzon manuscript extract, 7th SA Infantry Regiment).

The Brigade, under the command of Brig Gen P S Beves, received little training prior to its deployment in East Africa. While some officers and NCOs had received Active Citizen Force training and had gained war experience during the German South West African campaign in 1914 to 1915, the brigade in general arrived in East Africa illprepared for the campaign. Only three months passed between recruitment of the 2nd Brigade in November 1915 and its first action at Salaita in February 1916 (Collyer, 1939, p59).

The Battle of Salaita Hill

Salaita Hill, referred to by the Germans as 'Oldorobo' and located along the southern border of Kenya, was a principal centre for railway communications near Taveta. Since August 1914, it had been occupied by the Germans.

Maj Gen M Tighe, acting as the British Commander-in-Chief in East Africa while awaiting the arrival of Gen J C Smuts as the new C-in-C, proposed a plan to deploy the 2nd SA Brigade in a frontal attack on Salaita Hill. The South Africans would attack from the north-east through dense bush while the 1 st East African Brigade would take up positions in reserve immediately west of the Njoro Drift. No co-ordination of the movements between the two brigades was planned and, as a result, each brigade was to operate independently of each other (Collyer, 1939, p 53).

The British High Command greatly underestimated the strength of the German forces in possession of the Hill, believing it to be no more than 300 men, despite several forays and aerial reconnaissance sorties suggesting a larger contingent. In reality, the German and Askari forces, under the command of the now legendary Col (later Maj Gen) Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, amounted to between 1 300 and 1 400 men with a further six companies, amounting to 1 000 men, distributed in the area between Salaita and Taveta. This force also had an ample supply of artillery (Thompson, December 1987, P 128).

Beves was not at all happy with the plan. He pointed out the following to the GOC 2nd East African Division, Brig Gen W Malleson: that there would be no element of surprise during the attack; that the plan had not taken into account a possible German counter-attack from Taveta; that the South African brigade was short a battalion, as the 8th SAI had not yet arrived; and that artillery co-operation in dense bush was almost impossible. His appeals, however, were met with a supercilious response from Malleson and he was forced to inform his battalion commanders that the attack would proceed as scheduled (Ambrose Brown, 1991, pp 68-9).

The 2nd SA Brigade moved from Mbuyani to Serengeti on 11 February 1916. The next morning the Brigade marched out at 02:00 on route to a position situated 200m north-east of Salaita. Shortly after 07:00 the South Africans swung around and advanced south-west on the hill in a loose formation with the 7th SAI in the centre, the 5th SAI on the left and the 6th SAlon the right. As they entered the open grassland, the German forces on Salaita, under the command of Maj Kraut, opened fire with both artillery and machine guns. They had prepared fields of fire from specially selected entrenched positions and had also placed snipers in denser areas to fire into the backs of the attacking force. These positions were so camouflaged that a platoon commander of the 7th SAI thought that they were being fired upon by members of the 6th SAI who were advancing behind them! (Martin, 1969, p 210).

The casualties among the South African ranks began to mount up and, as the fighting continued, it became obvious that the strength of the German position had been seriously underestimated. It was also evident from the volume of fire that enemy reinforcements were being brought up. This was Capt Schultz's detachment from Taveta which, as Beves had feared, was moving toward the South Africans under cover of the hill in preparation for an attack against the South African right flank (Ambrose Brown, 1991, p 74).

At 11:00, in the knowledge that the attack on Salaita had failed, Beves took the decision to withdraw the 5th and 7th SAI in a north-easterly direction with the 6th SAI covering the retreat. The subsequent attack by Schultz's detachment, coupled with the fact that Askari snipers had been hiding in the baobab trees, caught the South Africans in the bush at a disadvantage and caused considerable confusion. Although there seemed to be very little panic, the South Africans fell back in scattered formations leaving their dead and wounded behind. Several platoons of the 7th SAlon the left of the Brigade lost touch and withdrew in disorder towards the 1 st East African Brigade, where the determined defence of the 130th Baluchi Regiment brought an end to the German charge (Martin, 1969, p 210; Ambrose Brown, 1991, P 76).

The dead and wounded lay dotted on the slopes of Salaita and the bush all around its foot. The South African losses were listed as 138. The 7th SAI regimental diary entry for 12 February 1916 records the battalion's casualties as 86, which included six killed, two who died later as a result of wounds, 51 wounded and 27 missing (7th South African Infantry Regimental Diary, Ditsong National Museum of Military History). Most accounts of the battle accept that the 2nd SA Infantry Brigade had been insufficiently prepared for the action at Salaita Hill, a view shared by von Lettow Vorbeck himself (p1 04), who noted that subsequent actions showed that the South African forces had gone to great lengths to make good their initial deficiencies in training.

Personal perspectives

In the initial writings of all three eye-witnesses selected to add a personal perspective to the battle of Salaita Hill, one senses a general feeling of adventure leading up to the battle. The Nongqai correspondent (p186) writes that, prior to disembarking at Kilindini in January 1916, ' ... a rumour came from the shore that on Thursday the Germans had made an attack on the railway line some 40 miles [64 km] away and that they were repulsed; we sustained only a few casualties. It sounds very interesting and I don't think our experiences in German South West Africa are likely to be repeated here as far as "looking for it" is concerned .. .' Private Thompson's expectant mood, expressed in his diary entry of 11 February after the brigade had received orders to march on Serengeti the following day, is similar (p129): 'Reveille 05:30. Sorted out kit bags which were left at the base. Took one blanket, slacks, socks, belt and cholera belt. Saddled up mules. Great fun watching mules that hadn't been broken in. Marched to Serengeti and made temporary camp. Came to rain about 13:00 and got under canvas covers. A good many chaps from the regiment took their clothes off and tried to get a bath in the rain but they were worse off than before. We have begun business properly now. At night got marching orders and were told we were to attack Salaita Fort. Great excitement.'

However, as the day of the attack dawned, this feeling of adventure began to turn into one of apprehension. In a letter the Nongqai correspondent (p 187) records: 'On Saturday 12 February 1916 we got right into it, and our troops on either side numbered some thousands. We marched for some time in the wee sma' oors [sic] and got in touch with them. This bush and the semi-jungle is the very devil. . .' In another letter, he adds (p 285) that ' ... on 12 February a further reconnaissance was made towards Salaita. We were told by our Colonel that the Germans were strongly entrenched at Salaita - that the South African Brigade was to move round the north of it, whilst the East African Brigade would attend to the east and south sides. Reinforcements for the enemy were expected to arrive from Taveta, which is about seven miles [11,2km] west of Salaita. The 7th were the advance guard to the column.

We moved off from Serengeti before daybreak and marched along the road for a little over a mile, then we went north-west over the Njoro, which only in the rainy season is a river.' From the informative tone of his writings, this unnamed correspondent appears to have been an officer, well aware of the movements being planned. In contrast, the privates, Head and Thompson, appear to be in the dark about the decisions being made.

In this regard, Private Head's description of the initial advance (p 7) is almost humorous: ' ... we left camp at 04: 15 in dead silence with absolutely no smoking, for no lights whatsoever were to be shown. I can, to this day [according to museum correspondence, he completed his manuscript in 1918] remember that quiet move, barely a sound coming from the whole column, on the soft sandy road, and all the fellows wondering what was in store for them, and what their first "scrap" would feel like.'

Under fire

What was it like to come under fire for the first time? Each of the three eye-witnesses featured here appear to have experienced their baptism of fire at Salaita Hill and provide detailed impressions of the advance and the initial action after the German forces opened fire on them.

The Nongqai correspondent writes (p187): ' ... the Germans are past masters in the art of entrenching themselves and fixing up tracks and decoy trenches etc. The 7th were in the advance of the attack and our boys went into it splendidly for youngsters or any other troops for that matter, in the face of shell and rifle fire. Some of us got up to within two hundred yards of the German entrenchments. I and my platoon did and how we got out again God knows; we lost a few. It was hot and we were under terrible fire - 08:00 to 13:00 - and now looking back, it seems about ten minutes of a jumble up of a contingent. The Germans had some Askaris up in the trees sniping and others down the lower branches of trees and bushes were covered with grass and bush. You simply could not spot them. It is frightfully bewildering to be fired at from the front, sides and rear at the same time. The officers are, of course, spotted and, without exaggeration, I am more than grateful to be writing this for, from the advance line, I was sent a couple of times to try and get reinforcements and was followed with bursts of Maxim fire. The Germans are great on machine guns and are clever at getting them about. There was one machine gun and gunner mounted on a mule and the whole lot covered with grass and bush and it was practically impossible to locate him but finally our armoured cars finished him off. You cannot imagine what tricks the Germans resort to. They planted a new Maxim at the end of the trench, waited for our men to get into the trench and then enfiladed them. They are very clever at this bush scrapping and we shall want a big force to effectually finish them off. It is going to take some time, that I feel certain about. We hope that it is true that Gen Smuts is en route; we think that his tactics will just be about equal to this sort of work.'

He followed up in another letter (p285):

'The bush is awfully thick. We now move west, our formation lines of platoons in fours. Behind our screen of scouts there was a good fifty yards distance and interval between each platoon. Just north of Salaita there was a clearing of some hundred yards and, as we came into this, fire was opened on us from Salaita Hill. I think the guns were probably a 7 -pounder and a 1-inch automatic the Germans have. Of course everyone got down and I think from this burst of fire only one man was hit, and that in the legs. After a few minutes the 7th got the order to attack. We deployed and the fellows, platoon by platoon, went up in beautiful style. I was with my platoon in the advanced firing line and we were within two hundred yards of the lower trenches around the hill. The 5th SAI attacked on our left and the 6th went on the right. This was at about 08:00.

Firing was going along merrily now and machine guns were rattling furiously, but few men were hit.'

Private Head recorded his impressions of the battle (p 7) as follows: 'Well, we arrived within two miles [3,2 km] of the fort at about 08:00 and halted on the downward of a hill looking direct at Salaita. The Huns lie Germans] must clearly have seen what our designs were, for through glasses every now and then one caught sight of them hustling about, getting things in general readiness for us, I suppose. While sitting there, a plane came over and after circling several times around the hill - the Huns fired on him with machine guns - made for where we were, and dropped a message. We then started to advance. We got some distance through the thick bush, and within 800 yards [731 metres] of the bottom of the hill, when all of a sudden we found ourselves fired upon by Pom Poms and another gun, which I have since been told was a Nordenfelt - so we lay down just as we were, which happened to be in column of fours, while these shells went overhead and burst to our rear. This did not last long, but why the Huns did not shorten their range and cause us trouble is only for them to explain. This being the first time the majority of us had ever heard a shell fired at us in earnest, it is only to be understood we got a bit excited, but under the leadership of our fearless Col F[reeth], he soon got us past the excitable stage.'

In this passage, it is interesting to note Head's description of the guns used against them by the Germans. The 37mm Maxim-Nordenfelt machine gun and the 'Pom-Pom' were one and the same weapon, which earned its nickname from the noise it made when firing. These guns were issued to German colonial forces at the start of the First World War and two are on display at the Ditsong National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Eric Thompson's description of the initial action (p 129) is equally vivid: 'We still advanced with the 6th SAlon our right and the armoured motors and headquarters staff on our left. We had advanced into an open space when suddenly we heard shells whistling over our heads and bursting about 30 yards [18 metres] behind us. At first there was a momentary pause then we all scampered for cover and a few more shells came along. For my part I was too excited to be frightened. After five minutes we were given the order to advance through the bush. Our howitzers now began firing and it was a fine sight, seeing the shells bursting around the trenches. We kept on advancing and the wounded began coming back.'

Pinned down

As described above, the Nongqai correspondent had become very aware of the Askari snipers hidden in the trees and even behind termite mounds. He observed that the 1 st East African Brigade's howitzer battery had begun shelling the German positions on Salaita. This shelling obscured the position of the Germans firing on them (pp 285, 362): 'Where our firing line was there was but little cover and to move meant inviting a fusillade. Occasionally a man was hit and he got away to the rear, unaided mostly. I was sent by Capt Ferguson of "D" Company to get in touch with the left of the line as a request had to be passed along from the right that, as the enemy were in force on that flank, reinforcements would be sent. Dodging along the left, I got into conversation with Lt Franck. He was in a scrub patch and told me that he had been shot in the knee. He said that he was alright and told me not to come near him. I looked around and decided that it would be better to get Franck to the rear if possible and I asked who would help me get him out. L/Cpl Jones volunteered to help. We got behind a bush and got ready to make a dash for Franck when we must have been spotted, and a burst of fire opened up on us. Poor Jones got a fatal wound just under the heart, it seemed to me. Franck was imploring us not to draw the line of fire on him. I saw Jones behind a bush and returned to Capt Ferguson to report that we were in touch with no-one on the left flank. Things were pretty busy on my part of the line then, and then word came along that we were pressed very hard on the right.'

Meanwhile, Private Head moved forward with his platoon toward the enemy position and also came under heavy fire. The advance slowed as the platoon began to take casualties and the South Africans found themselves pinned down in an exposed position (p9): ' ... the firing became heavier and heavier, if only one moved it was to start a hurricane of bullets in that direction. This went on until about 13:00 when it seemed as if we were being fired upon from both sides.'

Retreat!

The adrenalin pumps through the words of each of the three as the battle continues and, after the order is given to retreat, a sense of urgency and fear permeates their writing:

According to the unnamed Nongqai correspondent (p362), '[a]t about 13:00 the order was given to retire and then commenced the worst part of the affair, for we all got hold of some of the wounded - all we could find - whilst a few men covered our retirement. We had to re-cross the open patch again and it drew a perfect fusillade on us machine gun and rifle shots - and, as we drew off, the pam-pam shells whistled around. I don't know how we got out. About the other two regiments I cannot say anything. When we regained the thick bush north-east of Salaita Hill, the Loyal North Lancs held the line with the Baluchis and we got through their lines to Serengeti, being shelled some part of the way. Fortunately, many of their shells did not burst but just plunked into the ground. The Askaris followed up and they were drawn off by the 1 st East African Brigade.'

The order to retire came with some confusion to Private Head and the other men of his platoon (p 9): ' ... and then all at once it seemed as if we were on parade and had been dismissed, for all of us fellows were getting up and doing a sprint of perhaps 100 yards [91,4 metres] and then down. The truth soon dawned on us, we were retiring! And then we caught it, thick and solid, bullets whizzed past us, between our legs, and gave one the feeling that it would have been nicer to have been in a Pritchard St Tea Room at the time.' Head was clearly uncertain as to whether the order to retire was received or carried out at the required time. The German snipers along the way had an unnerving effect on their movement: ' ... at the time we were absolutely bewildered, for if we went one way, we were fired upon, turn and try the next and it was the same. Well, we made for the fringe of the bush, through which we had emerged early that morning in high spirits, but for which we were making as fast as we could, very dejected men, expecting to get one at any minute through the back. Oh! What a terrible sensation. It's bad enough if you get a bullet while advancing, but to think that one at this time was very likely to hit in the back way, gave one a creepy feeling. Just before entering the bush, I had the nearest shave to being hit; three of us were sitting behind an ant heap, when from goodness knows where, a bullet just missed hitting me in the thigh, entering the ground right under me. This we decided wasn't a healthy part, so we got up and away on our next little sprint. Once in the bush we collected fellows from all over the place, and got into some sort of formation, and started back to camp, the Loyal North Lancs and an Indian regiment covering our backs.'

At this point in his diary, Eric Thompson (p 129), expresses his own frustration and indignation, aimed particularly at the perceived lack of discipline of the 5th SAI: 'The 5th Regiment then began to retire and acted disgracefully, refusing to lie down when ordered. Our corporal then told us to retire right back so we retired till they began shelling us again so we lay flat down. It was at this point that I last saw Jock and Bob Thompson [his own younger brother]. We retired further and got behind some tall trees but they shelled us so we doubled across an open space to the right and got in "amongst the Indian Mounted Battery. We lay down for about half an hour with bullets zipping past all the time. The firing seemed to be coming nearer, the 6th retired behind us so we retired back and then to the right. My mule here bolted for the German line so I let him go and loaded my rifle and got behind an ant hill and there felt more comfortable. I waited for a few minutes, but as I could not see the enemy I retired further back as the snipers were getting all around us. I happened to find Lt Parsons and a few other chaps with the guns but no mules. A few minutes later Sober came up with his mule and, to my surprise, mine behind it. We saddled up as well as we could and then the Baluchis, who were guarding our rear, got behind us so we retired further and got behind some trees, but they began shelling us again so we got right out of it.'

Thompson continued: 'There was still one fairly sized exposed patch to cross but the Germans shelled us with 4-pounders but as far as I could see no damage was done. By this time I had finished my water and was terribly thirsty and tired. When we got to the railhead there were some tanks so I had a good drink and filled my water bottle. After a short rest I walked back to camp slowly and felt too tired for anything. I did not see Bibby after the first shots were fired so felt relieved when I saw him in camp. After our chaps had unpacked the mules they took the guns right up to the firing line and fired into the trenches. Several men of "D" Company of the 7th got into the first line of trenches but as the 5th would not support them had to evacuate the place. Hans Gosch was killed during the retreat. He was bending over when he was shot through the back, the bullet coming through the jaw and smashing it. The poor fellow said, "Take me out of this, I guessed it would happen on my birthday".'

The young machine gunner remained severely critical of the 5th SAI (p 129): 'Everybody reckons that, although it was a very hard position to storm, we would have won had it not been for the 5th retiring.' He could not have known that, after seeing Schultz's detachment deploying for a charge against the South African right flank, Beves had ordered the 5th SAI to fill the gap which had been opened between 6th and 7th SA!. W01 Molloy, Regimental Sergeant-Major of the 5th SAI, sets the record straight (Ambrose Brown, 1991, P 73): 'Shortly after the action began our regiment was ordered to move to the right flank of the 7th and fill the gap between them and the 6th as the enemy had by this time come up from Taveta.' Almost immediately, Beves cancelled that order and instructed the 5th SAI to retired some 200 yards [182 metres] to the rear to protect the 10th Mountain Battery. Molloy (Ambrose Brown, 1991, P 74) continues: 'Meanwhile Col Freeth of the 7th made an urgent appeal to Col Byron [Officer Commanding 5th SAI] to protect his left flank while he retired his regiment after ours. I found our gallant CO in the firing line in the open and about 200 yards from the enemy. Very properly, and without a moment's hesitation, he took the responsibility, disobeyed the general's orders and sent "D" Company to the help of the 7th. Our company remained on the scene half an hour after the retirement of the 7th. At this time the 6th were being pressed back by the enemy from Taveta. We sent another company to their help and shortly after they retired through our lines. We were then ordered to form a rear-guard for the general retirement of the whole force.'

Later, when the facts emerged, Thompson modified his opinion (p 129): 'On reading this entry recently, I would say that we had been rather harsh about the behaviour of the 5th SAI. As far as I recall it was the case of a few young chaps going into a panic and that should not be interpreted as a reflection of the whole regiment. The 5th did good work during the progress down the Pangani River and through Handeni to below the central railway. This regiment was the first of the 2nd Brigade to be repatriated to the Union, which happened in October 1916, but later, strongly reinforced, they operated again in the south-eastern region of East Africa.'

After the battle

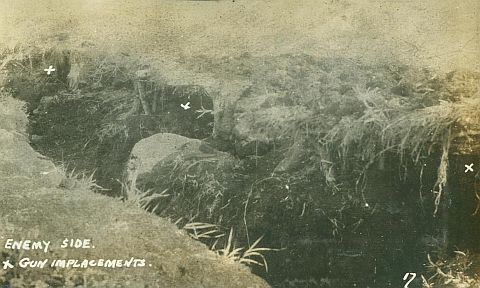

In describing events immediately after the battle, each of the three eye-witness accounts provides a different perspective. The serenity with which the Nongqai correspondent writes (p 362) is in direct contrast with the drama of the fighting earlier: 'We had a quiet night at Serengeti and on 13 February we returned to Mbuyuni Camp to refit etc. From the officers and men who have subsequently visited Salaita Hill, I learn that it was almost impregnable - concrete gun mountings and rifle pits beautifully concealed; barbed wire and everything to match. Of course, dummy trenches for the Germans were exceedingly clever this way.'

Private Head's style of writing is in typically satirical voice, perhaps as a means of making sense of the chaotic circumstances of the day (p10): 'As we were on our way back to camp and, on the crest of the hill from which we had that morning been looking intensively at Salaita, the Huns, just to speed us on our way, set a long-range 7-pounder gun on to us, put a few shells amongst us, scattered us a lot more, but did no material damage. There is one incident hereabouts that made a few of us laugh, but was of no laughable matter to the two men concerned in the joke. "Fritz" had fired his gun and we could hear the shell coming on its journey, so we "ducked" and it landed in a sandy patch about a hundred yards [91 metres] away, but practically on top of the two men in the story. It never exploded but merely made a terrible cloud of dust, but before that dust had time to settle or clear away at all those two fellows were beating all world records to get away from it. Do you blame them? Not me! Serengeti Camp seemed to have moved backwards that afternoon for it seemed as if we should never reach it, anyhow, after getting lifts on trains, wagons and motor lorries, we got back looking very sorry for ourselves and feeling very tired. Still, that didn't matter to those in command for we were immediately told to "dig in" in case the Huns, flushed by their victory, should follow us up. So we set to and made some sort of cover for ourselves which we finished by about 17:30, most of us then stretching out and going to sleep. It should be stated that, at the railhead, about a mile [1,6 km] past the camp, there were a number of water tanks which had carefully been filled with water brought all the way from Burra. That night the Huns got as far as those tanks and of course they were not going to go away without spilling something. As they did not fancy us, they evidently took a liking to the water tanks and our precious water soon went. Next morning found us a very dry crowd and we had to go pretty short. '

Eric Thompson, for his part, came away from the battle feeling fatigued and weary (p129): 'Towards the end of the day I was so tired that I felt as though I didn't care what happened. We had nothing to eat all day except three biscuits and a cup of coffee at about 03:00 before we left camp. Although I expect some more fighting I hope we never get under such heavy fire again. When we got back to camp we had to entrench ourselves and bury the poor chaps who had been killed.'

The human story

It is clear that eye-witness accounts allow the ordinary person to express his or her individuality and play a part in creating historical awareness. The versions of events described here by the unnamed officer, Private Head and Eric Thompson add considerably to the historiography of the battle of Salaita Hill by providing a glimpse into the lives and thoughts of men who were actually there. Each of the three accounts highlighted here tells a story of the human side of the battle. Where else would one get a sense of their spirit of adventure and excitement prior to the battle, their growing apprehension during the initial advance on the enemy position, their rush of adrenalin and feelings of vulnerability as the attack falters and the order to retreat is given, and their individual summing up of the event after the guns grew silent.

Yet, personal accounts in military history have limitations, causing historians to approach them with caution. Problems that may cast doubt on their reliability as sources of historical evidence include a fading or selective memory, deliberate embellishments or omissions, self-aggrandizement, and a reluctance to associate others, or even themselves, with particular events. Thus the evidence obtained from these first-hand sources needs careful evaluation and should be used in conjunction with other sources (Tosh, 1987, p 215).

The Battle of Salaita Hill was an important battle in South African military history. It exposed the misguided belief of the invincibility of the white South African soldier following the recent success in the German South West African Campaign of 1914 to 1915. The evidence of the three eye-witnesses brings into sharp focus the contribution of these men to the historiography of the battle. Their voices cannot be ignored. Despite the limitations of this type of account of past events, one might ask whether history can ever present a complete story without the use of personal, human stories.

Bibliography

Ambrose Brown, J, They fought for King and Kaizer, South Africans in German East Africa (Ashanti Publishing, 1991).

Collyer, J J, The South Africans with Gen Smuts in East Africa, 1916 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1939).

Curzon, Dr H H, 7th SA Infantry Regiment' in 'Curzon Unpublished Manuscripts', Library File A.412(68), Archives, Ditsong National Museum of Military History.

Head, R, 'With the 7th SA Infantry in German East Africa, 1916-1917' and correspondence between the donor and the South African National Museum of Military History in Library File 920 R Head, Archives, Ditsong National Museum of Military History.

Martin, A C, The Durban Light Infantry, Volume 1 (Durban Light Infantry, Durban, 1969).

Nongqai magazine, Volume V, 1916, article by unnamed correspondent.

Personal correspondence with Prof D F S Fourie, Professor of Strategic Studies, UNISA (Rtd), August 2014.

7th SA Infantry Regimental Diary', Library File A.412 (68), Archives, Ditsong National Museum of Military History.

Thompson, P R, The Voices of the Past - Oral History (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1978).

Thompson, E S, 'A Machine Gunner's Odyssey through German East Africa' in Military History Journal, Volume 7 No 4, December 1987.

Tosh, J, In pursuit of history - Aims, methods and new directions in the study of modern history (Longman, London, 1987).

Von Lettow Vorbeck, P E, My Reminiscences of East Africa (Hurst and Blackett, London, no date).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org