The South African

The South African

On 7 October 2014, after an early departure from Bruges, Belgium, our party of 20 Hoërskool Waterkloof learners, two teachers and the experienced guide, Filip Debergh, were on our way to the Flanders Battlefields. For many a learner, it would be a life-enriching experience.

It was precisely one hundred years ago to the day when the first German soldiers arrived at Ypres during the so-called First Battle of Ypres.

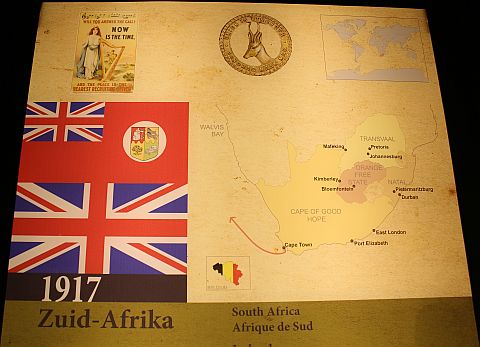

The previous day the learners had attended a lecture on South Africa's involvement in the First World War in an auditorium at Sint-Leocollege in Bruges, a school with which Hoërskool Waterkloof has had an exchange programme for the past seventeen years. The learners gained insight into the continents and countries in which the South African soldiers had fought, the horrors of the Delville Wood, the mud in Flanders, the tragedy of the South African Native Labour Contingent on board the SS Mendi, and the soldiers' unique mascots, Nancy the Springbok and Jackie the Baboon.

Filip Debergh selected the various places to visit, since there are about 150 war cemeteries around Ypres.

Vladslo German War Cemetery

Our first stop was the Vladslo War Cemetery. After the war, many German soldiers were reburied at Vladslo cemetery, a few miles north of Ypres. The cemetery contains the graves of thousands of men killed in the early days of the war. Over 25 000 soldiers are-buried in this German war cemetery. In German war cemeteries, the soldiers' burial places are marked by black slabs laid flat on the ground.

Among the graves is that of Peter Kollwitz, a student from Berlin who had volunteered as soon as the war broke out. Two months later, in October 1914, he was killed, aged eighteen, in one of the war's first major campaigns. His mother, Kathe Kollwitz, a prominent German artist, sculptor, socialist, feminist and pacifist, was informed of her son's death and, by December, had formed the idea of creating a memorial to him. In April 1931, the hugely moving Grieving Parents sculpture was erected, adjacent to her son's grave.

The autumn leaves were falling and many black slabs were covered by oak tree leaves. One could appreciate the sacrifice which the young German soldiers had made for their Fatherland.

Dodengang (Trench of Death)

During the desperate fighting of October 1914, the Belgians had opened the sluices on the River Ijzer (Yser) and so prevented the Germans from overrunning Belgium entirely. The corner of West Flanders behind the Yser was never taken. Located 2 km north of Diksmuide, this 400 metre stretch of preserved Belgian trenches has been carefully preserved 'Lest we forget'. Allied troops called it the Trench of Death and spent four years here, bravely holding the Front Line. The Trench of Death was hit hard during the First World War. Just 20 metres from the trench, on the other side of the Yser River, German troops were positioned in a bunker.

The Trench of Death's visitors' centre presents a clear picture of the appalling conditions on the front during the First World War. Ironically, while they were in the trenches, the Hoërskool Waterkloof learners experienced heavy rain and were soon soaked through. In the wet conditions, we met South African learners from Hoërskool Outeniqua, who were also visiting the battlefields.

Ijzer Tower

Wet and cold after experiencing the Trench of Death, we stopped at the Ijzer Tower. It was still raining heavily and the wind was blowing strongly. I was the only one to brave the weather and made it to the foot of the tower, but the bad weather changed my mind and I was soon back in the comfort of the bus.

The Flemish frontbeweging (Front Movement) began in this area as a protest against a state that expected the Flemish to die for Belgium yet showed no respect for the Flemish language or culture. There was no question of mutiny, but the implications were still profound for the future of Flanders. Close to Diksmuide, the Ijzertoren (Ijzer Tower) is a significant memorial to the Flemish who died in the war on a piece of land that had once been a notoriously dangerous spot opposite a German artillery battery, the Ijzervlakte. The Ijzertoren was built in 1925 in protest against a decision by the Belgian War Graves Commission to use 500 Flemish gravestones to make gravel for roads. An annual pilgrimage started in 1920 to the grave of the half-Irish artist, Joe English (1888-1918), who had designed a gravestone specifically for Flemish soldiers in the shape of a Celtic cross with the characteristic AVV-VVK symbol, and the blouwvoet or fulmar, another Flemish nationalist symbol. The abbreviation 'AVV' stands for 'Alles voor Vlaanderen' (All for Flanders) and 'VVK' for 'Vlaanderen voor Kristus' (Flanders for Christ).

Scottish Monument Frezenberg

We also made a short stop at the Scottish Monument in Flanders, which includes a South African memorial plaque. The Scottish Monument in the vicinity of Frezenberg, Zonnebeke, was unveiled on 25 August 2007. The choice of location for a national Scottish monument could not have been more appropriate.

The monument was erected on the edge of the area where the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division launched a bloody attack on 17 August 1917, with an impressive view of the battlefield where the action took place. Only weeks after' that attack, the 9th Scottish Division, which included the

1st South African Brigade, took over the sector and participated in the Battle of Menin Road on 20 September. Poppies grow close to the monument and many a learner picked 0ile as a souvenir of the interesting day spent in the battlefields.

Tyne Cot

Tyne Cot is the world's largest Commonwealth War Grave Commission cemetery and the final resting place of almost 12 000 souls. The sight of its uniform gravestones stretching into the distance is utterly humbling. Over 70% of them belong to unidentified British or Commonwealth soldiers and bear the words 'Known unto God'. The cemetery takes its name from a barn that once stood at the centre of this German strong point, and which British troops presumably thought resembled a Tyneside cottage. The Germans had a couple of blockhouses or 'pillboxes' here which they used as Advance Dressing Stations (ADS). Several have been preserved, including one beneath the mighty Cross of Sacrifice erected in 1922. By climbing a few of its steps, one catches a glimpse of the Germans' advantageous viewpoint overlooking the British lines and Ypres. It was this high ground for which the British fought during the Third Battle of Ypres, which began on 31 July 1917.

In visiting the cemetery, what struck the learners in particular were the wellkept lawns between the graves where officers and other ranks all have the same plain white headstone carved with their regimental badge/country and whatever details are known about them. Many small South African flags were planted in the soil by Hoërskool Waterkloof learners near the graves of almost 100 South African soldiers who were buried there.

It was also interesting to visit the graves of the three unknown South African soldiers whose remains were discovered on 23 September 2011 near Zonnebeke and were reburied at the Tyne Cot Cemetery on 9 July 2013. Two learners, Nicholas Ferns and Liane Badenhorst, gave an overview of South African soldiers' involvement in the war and read the well-known fourth stanza of Laurence Binyon's poem, For the Fallen. The rest of the learners placed a few South African flags at their graves.

The Brooding Soldier

(Canadian monument and site of the first gas attack on 22 April 1915)

One of the most controversial aspects of the First World War was the gas attacks. Visible for several miles beside the main road from Ypres to Bruges, is the impressive Canadian memorial at St Julien. The memorial stands like a sentinel over those who died during the heroic stand of the Canadians during the first gas attacks of the First World War on 22 April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April to 25 May 1915). It is one of the most inspiring of all the battlefield memorials on the Western Front. Rising almost eleven metres from a stone-flagged court, The Brooding Soldier surmounts a single shaft of granite - the bowed head and shoulders of a Canadian soldier with folded hands resting on arms reserved. The expression on his face beneath the steel helmet is resolute yet sympathetic, as though its owner is meditating on the battle in which his comrades displayed such great valour. The statue is set in the middle of a garden surrounded by tall cedars, which are kept trimmed to perfect cones to match and complement the towering granite shaft. By then the weather had improved and we could walk around this impressive memorial.

Memorial Museum Passchendaele

The large number of visitors and school groups to the museum impressed the South African learners. Inside Kasteel Zonnebeke, a 1920s mansion, the Memorial Museum Passchendaele has been transformed in time for the centenary. In the old section, there is a collection of weaponry, uniforms and an immersive trench 'experience' complete with corrugated-iron walkways, bunker rooms, dimmed lights and a war-sounds soundtrack.

The brand-new wing explains, via a large-scale model, the course of the 100-day Battle of Passchendaele that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of soldiers in 1917, as well as how trench design developed over the years, with examples showing the differences between German and British versions.

The Remembrance Gallery houses a sculpture by New Zealand artist Helen Pollock. It is made from clay scraped from the soil in Passchendaele and Coromandel in New Zealand.

Artefacts found with the remains of the three South African soldiers, discovered only in 2011 near Zonnebeke, were also on display. The Springbok badges that were found with the bodies unmistakably identify them as South African soldiers.

Hill 60

Due to the extremely wet conditions, the visit to the huge Caterpillar Crater at Hill 60 was cancelled. This was the site of the most violent explosion in any war before the first atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

Menin Gate (Meninpoort) in Ypres

The learners also visited Ypres, which was hit by six million shells in the course of the First World War. Nothing was left standing. Sir Winston Churchill and others were keen to leave the city in ruins as a memorial to the dead, but the citizens of Ypres disagreed and returned to rebuild their town once the war had ended.

The monumental Menin Gate was built as a memorial to the dead. Erected in July 1927, the Menin Gate marks the spot where soldiers would leave town on the way to the front line. Carved into the interior walls are the names of 54 896 British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in the First World War and whose graves are unknown. Soldiers who went missing after 16 August 1917 have had their names inscribed on the arches at Tyne Cot Cemetery.

The Menin Gate was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and its construction began in June 1921. Blomfield, who was classically influenced, planned a great triumphal arch in the Roman tradition. Owing to running sand beneath the planned foundations, huge concrete piles had to be driven 36ft (11 metres) into the ground. The Menin Gate is made from French limestone and, with a mass of 20 000 tonnes, it is 135ft (41 metres) long, 140ft (42,6 metres) wide and 80ft (24 metres) high, dominating Ypres along with the rebuilt Cloth Hall.

Of the dead, General Plumer said, 'They are not missing - they are here'. Siegfried Sassoon, however, called the Menin Gate 'a sepulchre of crime'.

The Hoërskool Waterkloof learners visited the Menin Gate in the daytime and were informed about the different aspects of the monument. For the children to see familiar surnames such as Du Toit, Nel, Swart, Van der Walt, Prinsloo, Van Zyl, Els and Ferreira to name but a few, brought home the message of also Afrikaners' involvement in the First World War and underlined the ultimate price they paid for freedom.

After enjoying some free time, the learners returned to the Menin Gate about an hour before the official sounding of the 'Last Post' was to start. There they met the friendly Colonel Ryna Fondse, South African military attache in Belgium, who had travelled from Brussels to meet our group and to be part of the official ceremony. Most of the Hoërskool Waterkloof learners, with two (Dirk-Philip van Der Berg and Francois Karg) carrying the South African flag, were positioned behind the local fire brigade which would play the 'Last Post'. The school anthem and, later, the South African national anthem, were sung as part of the official ceremony. A Canadian band also played under the Menin Gate that evening and was also part of the official ceremony. The Canadian anthem was played by the band and sung under the Menin Gate. Two Hoërskool Waterkloof learners, Mericia Els and Libbi Stannard, alongside Colonel Fondse, carried wreaths and put them against the wall during the wreath-laying ceremony.

The 'Last Post' at Menin Gate

As a mark of respect, the road is closed every evening at 20.00 and members of the local fire brigade sound their bugles. Known as the 'Last Post', this tribute to the fallen has continued uninterrupted since 2 July 1928, except under German occupation during the Second World War, when the ceremony was instead conducted in Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey. However, the ceremony was performed on the same night the German forces were expelled.

A verse from Laurence Binyon's poem, For the Fallen,' is also read aloud. On 9 July 2015, the 'Last Post' will be sounded for the 30 000th time under the Menin Gate.

Reflections of war

After undertaking these battlefield tours, things like the origins of the famous South African ultra-marathon, the Comrades, started making sense to the learners. It is good to know that Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa visited Delville Wood, France in 2014 and Former State President FW de Klerk visited the Tyne Cot Cemetery in 2013. More can certainly be done by South Africa to recognise the centenary of the First World War if one considers the involvement of the governments of Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. During our stay in Western Europe we noted almost daily media coverage of news of a commemoration of the First World War.

A visit to the Tower of London in England to see all the ceramic poppies concluded our tour. Hopefully, a seed has been sown to remind learners about the horrors of war and to honour our war dead. To quote the last phrase in Laurence Binyon's For the Fallen: 'At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them'.

REFERENCES

De Vries, A, Flanders: A Cultural History (Signal Books, Oxford, 2007), p 296.

Digby, P, Pyramids and Poppies: The 1st SA Infantry Brigade in Libya, France and Flanders 1915-1919 (Ashanti Publishing, Rivonia, 1993), p 444.

Ruler, J & Thomson, E, World War One Battlefields: A Travel Guide to the Western Front (Bradt Travel Guides, England, 2014), p 90.

Van Wyk, J, 'Touring the Battlefields 20 September 2007' in Military History Journal, Volume 14 No 2, pp 42-47.

Acknowledgements

The learners and teachers wish to thank Mr Daan Potgieter, Headmaster of Hoerskool Waterkloof, and the school's Governing Body, for the opportunity to experience this enriching exchange programme. Sint-Leocollege and its teachers, especially Filip Debergh, Peter Vandaele and Siska Demarest, and the parents and learners were wonderful hosts. A word of special thanks goes to Hester-Susan van den Berg for her magnificent organisation during this exchange programme. [Web-site editor's note: the photographs - all by J van Wyk - were not in colour in the printed article.]

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org