The South African

The South African

* The evocative description, 'the red harvest of the Somme', is used by Lewis-Stempel (2011, p 213).

** The reference to schools as munitions factories comes from a wartime address by the headmaster of St Andrew's College (see below).

About the author

A former attorney, Matthew Marwick has taught history and economics at his old school, Maritzburg College, since 2004. He is currently the Director of Boarding, chairs the school's Archives Committee, and coaches the 8th XV. A former guardsman in the State President's Unit (1989-1990), he is married to Kirsten and they have two young sons.

Introduction

It is appropriate that, as the centenary of the start of the First World War passes us by, we continue to recognise and honour the millions of men who perished in that grim death-struggle. The Great War Roll of Honour of men from the former Union of South Africa amounts to between 8 500 and 9 500. While this number is miniscule in comparison with the seemingly endless slaughter endured by the main protagonists - after all, the British Army suffered nearly 20 000 soldiers killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme alone - the relative suffering amongst pockets of South African communities was considerable. Also, while it remains of some comfort that the men who died, especially at Delville Wood and aboard the SS Mendi, collectively remain to a degree, even now, nearly 100 years after those events, within the public memory, it is sad to have to admit that so many of our 'Fallen', who gave up their lives pro patria, have receded into the faceless anonymity of the now distant past. That is, apart from being acknowledged at Remembrance Day parades at a few dozen high schools. No doubt, the seemingly blind patriotism of those colonial recruits of 1914 towards 'Mother England' and their support for its principled stance to defend neutral Belgium would fail to resonate with many contemporary young men, raised on video games, Coca-Cola and Miley Cyrus. What is perhaps less surprising is the fact that a sizable minority of the young men of 'the Union' who died 100 years ago emerged from a small pool of English-speaking high schools - including many of the country's most celebrated institutions of today - most of which had unashamedly been moulded on the leading public and grammar schools in Britain.

They rallied to the call ...

Of the total of 8 551 white South Africans who (according to at least some sources, including Lambert (2004, pp67-86)) died in the First World War, nearly 1 300 were educated at just seventeen schools. A staggering 164 old boys of the South African College High School (SACS) perished, while St Andrew's College in Grahamstown and the Diocesan College (Bishops) lost 125 and 113 of their alumni respectively, with the last-mentioned enjoying the distinction of having the honours and awards earned during the War by its old boys brought to the attention of the House of Commons (Lambert, 2004, p 84). The old boys of my own alma mater, Maritzburg College, honoured its martial motto - recognising eleven old boys who had died defending 'hearth and home' in the Colonial Wars - and about 800 of them rallied to the call. Sadly, of these, three masters and 97 old boys died during the War. Other so-called 'traditional' English-speaking boys' schools lost over 50 of their alumni during the War: 93 Dalians perished, as did 86 boys from Durban High School, 80 Queenians, 66 boys from the newly-established King Edward VII School in Johannesburg, 61 boys from Kingswood College, 60 boys each from St Patrick's CBC (Kimberley) and St John's College, 59 boys from Grey High School, 56 boys from Rondebosch Boys' High School (including three masters), 52 Hiltonians, and 50 each from Graeme College, Kimberley Boys' High School and Selborne College.

In an article titled 'Munitions factories' (notably, the title comes from a wartime address by the headmaster of St Andrew's College, Rev Canon P W H Kettlewell [19091933], in which he refers to schools like St Andrew's being 'munition factories ... turning out a constant supply of living material'), the author, Prof John Lambert, described the sacrifice of the old boys of these traditional South African schools. These young men, having been infused since their school days with the now decidedly Victorian notions of duty and sacrifice, with tales of derring-do on the Indian frontier, and with the noble ideals of Rev Thomas Arnold's 'muscular Christianity' at Rugby School, rallied to the British flag, and were shipped off to die in German South West Africa, in East Africa, 'on Flanders Fields where poppies grow', in Palestine, and at Gallipoli (Lambert, 2004, pp 67-86). In many cases they had no doubt been enthusiastically cajoled and even cudgelled by jingoistic schoolmasters, bristling with splendid whiskers and thrilling tales of skirmishes with Africans and Boers. One thinks of the almost romantic (these days) figures of the Edwardian schoolroom - men like the mighty A S 'Madevu' Langley at Durban High School, who had cut his teeth as a junior schoolmaster under that fellow arch-Victorian, Maritzburg College's R D Clark. A man of 'brooding ferocity', Langley had served as an officer in the Natal Carbineers during the so-called Bambatha Rebellion of 1906. The schoolboy rumour of the day had it that his drooping left eyelid had been caused by a wound from a spear during that ill-fated conflict - but more about him later.

These young colonial men rallied to the call in their thousands, mirroring to an admirable degree the example of public school sacrifice best exemplified by the famed Eton College, which lost a staggering 1 168 (or 21 %) out of 5 656 past scholars who served in the First World War, 'their names etched in bronze along the wall of the school's manicured Cloisters, an eternal memorial to the selfless nobility of the 'flower of English manhood'. Not surprisingly, all the famous British public schools were decimated - albeit none quite to the degree of Eton: 733 boys from Marlborough (21%) died out of 3 418 who served, 707 (20%) from Wellington, out of 3 500, 687 (20%) from Charterhouse, out of 3 500, 686 (21%) from Rugby, out of 3 244, 675 (19%) out of 3 540 from Cheltenham, and 644 (22%) from Harrow, out of 2 917. Elsewhere in the old Empire, the large Australian public schools endured some of the longest casualty rolls, with 302 boys from Sydney Grammar School dying in the War, out of 1 772 who served (17%), 212 from Scotch College in Victoria, out of 1 247 (17%) and 209 from Melbourne Grammar School, out of 1 370 (15%). In New Zealand, 285 boys out of 1400 (20%) who served from Auckland Grammar School died, and 157 from Otago Boys' High School. Upper Canada College in Toronto lost 176 (or 16%) of its old boys, out of 1 089 who served.

The sacrifices made by the British public schools were staggering - and the elite Etons, Harrows and Winchesters (and schools of their rarefied ilk) did not have a monopoly on the suffering that ensued. For example, the archives of the less socially prestigious Glasgow Academy contains a photograph of eleven of its old boys serving in the Scottish Rifles posing proudly for the camera before their departure for Gallipoli in December 1914; eight of them were to be killed on one day, 28 June 1915 (Seldon and Walsh, 2013, p 49). But, inevitably, the large public schools with long-established martial traditions like Eton (which had 1 028 schoolboys on its roll in 1914) offer some of the best - and thus most poignant - examples of collective sacrifice.

Today, almost a century after their battlefield deaths, one can but marvel at the unflinching devotion to duty and the heroism of these former public schoolboys, some of whom were only weeks out of school. And one can also only admire the sangfroid with which some of them were able to face what to many must have seemed inevitable - their own deaths in No-Man's-Land, a bullet-hole through the stomach. One thinks of Lt-Col Hon Lawrence Polk (Wellington) DSO of the 1st Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment, who, on the bloody first day of the Battle of the Somme, donned his best uniform with white gloves and led his men across No-Man's-Land carrying his walking stick. He and all 25 officers under his command were killed or became casualties (Seldon and Walsh, 2013, p57). Another amongst the scores of memorable tales about young ex-public schoolboys on that grim day detailed by Seldon and Walsh (2013, p 59) is Captain Billy Nevill (Dover College), who had been somewhat of a hero at school, where he had been head boy and captain of cricket and hockey. 'Commissioned into the 8th Battalion East Surrey Regiment, he wrote home four days before the Somme opened in almost a parody of blase unconcern: "As I write the shells are fairly haring over; you know one gets sort of bemused after a few million. Still, it'll be a great experience to tell one's children about. So long, old thing, don't worry if you don't hear for a bit. I'm as happy as ever." In the same spirit, he had purchased four footballs, one for each of his platoons, to be kicked as they crossed No-Man's-Land. His aim was to make his men, who he knew would be afraid, more comfortable.'

A similarly light-hearted tone was adopted in his brief farewell note to his parents by Old Etonian 2nd Lt Logie Legatt of the Cold stream Guards, hours before going 'over the bags' in the 3rd Battle for Ypres in 1917. Described as one of the 'school's sporting greats', he had played in the 1912 XI that had vanquished Harrow at Lord's, and at the end of his final year at school had 'led a famed College Wall team that put paid to Oppidan hopes on St Andrew's Day'. He wrote as follows: 'Well old things, tomorrow it happens ... There's a deuce of a noise going on ... But I'm feeling very fit and keen and calm; far less excited than [at] Lord's ... I feel that it is out of my hands now and I pray merely for guidance and courage. Needless to say I'm wearing my Wall scarf, symbol of victory ... So goodbye and thank you once again' (Churchill, 2014, p 284). After a superb advance by the Guards, Legatt was killed later on that morning as he was walking up and down the parapet, 'as cheerful as ever' (Churchill, 2014, pp 286-7).

As Seldon and Walsh note (2013, p 59), '[left] and right wing, sportsmen and aesthetes, the fearful and the fearless; the Somme claimed them all'

It is commonly acknowledged that if naivete and loyalties to the old world order may have perished amidst the bombs, mud and slaughter of the Somme, then so did many of England's very 'best' - lantern-jawed young varsity men in their bow-ties and boaters who, to paraphrase Blackadder Goes Forth, merrily played hop-scotch outside the recruiting office. These young men, brimming with dreams of martial glory, were catapulted from school Officer Training Corps (OTC) parade grounds basking in the dying rays of Edwardian England to the limb-strewn battlefields of a very modern war. They were the ones who perished early - we have already seen how the young subalterns from Eton, Marlborough, Wellington et al perished in their droves, especially amidst the mud of the Western Front.

In South Africa, the statistics were to a degree similar. The average fatality ratio of South African troops who served in the First World War was about 8.5% (ie 1 in 12), whereas in the British Army it was about 11 % (Seldon and Walsh, 2013, p 1) and 18% for the old boys of public schools, one third of whom were subalterns. At Wynberg Boys' High School and Grey High School it was 8% (nearly 1 in 12), at King Edward VII School it was 9% (1 in 11), at Rondebosch it was 10% (1 in 10), at Jeppe 11 % (1 in 9), at St Patrick's CBC and Maritzburg College it was 13% (1 in 8), at Hilton, St Andrew's and Bishops it was about 14% (1 in 7), at Kingswood it was 16% (1 in 6), and at DHS it was 17% (under 1 in 6). The old boys of Michaelhouse and St John's College, those two distinguished, yet rather fledgling, schools came closest to matching proportionally the sacnflces made by the British public schools. A total of 46 Michaelhusians perished (including three members of staff), out of only 198 who served (23%), and at St John's 60 old boys out of 299 who enlisted did not return (20%).

An impressive tally of 190 decorations was earned by the over 800 old boys of Bishops who served in the War, and the alumni of other traditional schools also received an admirable number of awards, albeit not as many. For example, St Andrew's old boys received 102, and old boys from Maritzburg College 61, Hilton 43, King Edward VII 36, Jeppe 23, Selborne 20 and Michaelhouse 12.

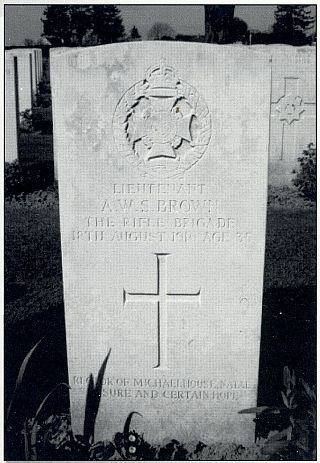

Teachers at the front

Michaelhouse enjoys the sad distinction of having had the only headmaster of a British and Empire public school to die as a result of enemy action in the War (Seldon and Walsh, 2013, p 115). Anthony Brown had only joined the staff of the Balgowan school in 1910, having moved from his alma mater, Uppingham, and in August 1915 he was granted leave of absence by the Bishop of Natal to enlist. Commissioned into the Rifle Brigade, he was shot dead by a long-range sniper near Guillemont on the Somme in August 1916 (Barrett, 1969, p 61). As an aside, the headmaster of Jeppestown High School (later Jeppe High School for Boys), J H A Payne, died of fever in 1917, while on service in East Africa - but then Jeppe is not a 'public school' in the sense used above.

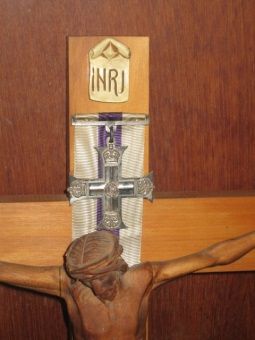

Other headmasters and future headmasters were to serve with distinction during the Great War. For example, Lt-Col E G 'Oubaas' Gane served Kingswood as its headmaster from 1892 until 1927 and was described as 'every inch a military man'. During the War, he served as a colonel in the Middlesex Regiment (Kirkby, Kirkby and Leigh, 1994, p 51). Lt (future Lt-Col) A C 'Betsy' Martin, a product of Maritzburg College, earned a Military Cross, and was thereafter not only the commanding officer of the Royal Durban Light Infantry but the headmaster of DHS (1943-1952) (Haw and Frame, 1988, p 215). Former St Andrew's Rhodes Scholar Ronald Currey earned an MC and bar with the Black Watch and in due course was to serve both Michaelhouse as its rector (1930-1938) and his alma mater in Grahamstown as its headmaster (1939-1955) (Barrett, 1969, p 96).

The seventh headmaster of St John's College, Old Carthusian Lt-Col Fr Charles Runge, earned an MC and bar and a DSO (Lawson, 1968, p 218). However, one doubts whether any teacher offered a better example than Runge's predecessor at St John's, Father Eustace Hill, who famously served as an Anglican chaplain to the 'Springbok Brigade' at Delville Wood. Although he received an MC for fearlessly attending the wounded during the battle, such was his utter disregard for his own safety that (as was described in an article that appeared in Grocott's Penny Mail at the time) '[the] men declare that he won the VC again and again'. At Butte de Warlencourt three months later he lost his right arm while again rescuing wounded men in No-Man's-Land, and in early 1918 he was taken prisoner (Lawson, 1968, pp 127-8, 218).

A savage toll

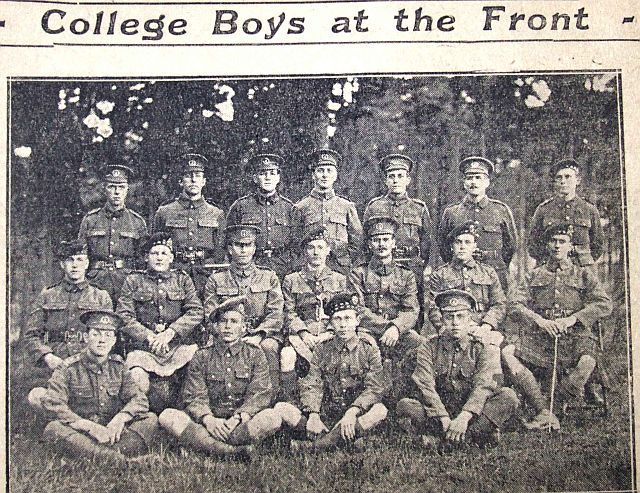

For a school archivist, many of the most poignant photos that emerged from or were related to the War were those of groups of old boys before they went into battle (including of school sports teams), and I have already referred to the Glasgow Academy photo of December 1914. For example, all fifteen of the triumphant DHS First XV of 1914 volunteered for service, of whom four were to perish (Jennings, 1966, p 137).

Once again, the sacrificial example of Old Etonians is a telling one: the dozen players (including the 12th man) who made up the triumphant XI of 1912 that prevailed over Harrow in the annual Lord's encounter fought on seven fronts, won three DSOs amongst them, had one of their number captured as a POW and lost five killed in action (Churchill, 2014, p 287). In an article from The Witness dated July 1916 there appears a photograph of old boys of Maritzburg College who gathered together in France shortly before the start of the Battle of the Somme (of which Delville Wood was but a part) on 1 July 1916. Titled 'College Boys at the Front' (see photo below), it depicts eighteen young servicemen, of whom eight were to perish before the guns fell silent in November 1918 (Löser, 2014).

Not unexpectedly, the Battle of Delville Wood claimed an especially savage toll on the South African schools. For example, twelve old boys from Durban High School died during the course of the seven-day battle (with a further nine wounded and three captured). Ten boys from St Andrew's were killed; nine boys from St Patrick's CBC and seven boys from Kimberley Boys' High died. Of the fifteen old boys from Wynberg Boys' High who fought in the battle, seven were killed and four were wounded. Seven old boys from Maritzburg College were killed, as were five from Michaelhouse. Of the twelve St John's boys who went into battle, five were killed and five were wounded. Four boys from Bishops were killed, as were four past pupils of the Boys' Day Continuation School (now Glenwood High School), which, after all, had only been founded in 1910. Indeed, of the eleven boys from present-day Glenwood who survived the battle, seven were to die between October 1916 and March 1918, with the youngest amongst them being W J K Calder, the holder of the Military Medal yet still only a lad of under seventeen years of age at the time of his death (Jordan and McCabe, 2000, p 33).

Decorations

Notably, the majority of the Victoria Crosses earned by South African-born servicemen in the First World War were earned by the products of these traditional schools.

Capt Oswald Reid had spent a while at Bishop's, before finishing off in a blaze of glory at St John's College, where he was captain of cricket and football and Senior Prefect. He won his VC on 8-10 March 1917 defending a position on the Dialah River in Mesopotamia (Lawson, 1968, p 132-3).

Acting Lt-Col John 'Jack' Sherwood Kelly, DSO, CMG won his VC on the Western Front at the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. He had been educated at Dale, Queen's and St Andrew's colleges - and expelled from all three! (Stevens, 1 990, P 114-5.)

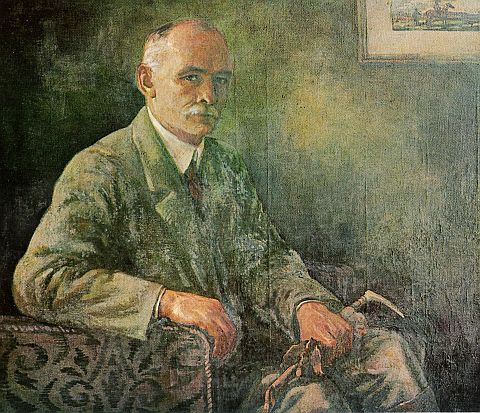

Acting Capt Reginald Hayward, MC and bar (photo above), had been schooled at Hilton. He earned Britain's highest award for valour on 21-22 March 1918 near Fremicourt, France, when he 'displayed almost superhuman powers of endurance', having been buried, wounded in the head and rendered deaf on the first day of operations and had his arm shattered two days later (Nuttall, 1971, P 57).

The diminutive, highly-decorated 'balloon buster', Lt Andrew Beauchamp-Proctor, DSO, MC and bar, DFC, had attended both St George's Grammar School (founded in 1848) and the country's oldest school, SACS (Coyne, 1997, p 25), and was awarded the VC nearly three weeks after the 11 November 1918 Armistice. This was in recognition of a two-month period between 8 August and 8 October 1918, when he took part in 26 decisive combats, in which he destroyed 12 enemy kite balloons and 10 enemy aircraft, and drove down four other enemy aircraft completely out of control. One certainly can raise the argument that he, with a VC and four other gallantry awards, was South Africa's most highly decorated serviceman of the War.

Amongst the most highly decorated South African soldiers was Brig-Gen William Tanner, who had been schooled at Maritzburg and Hilton colleges. He had been the battlefield commander at the Battle of Delville Wood until evacuated early on in that grisly affair with a leg wound. For his leadership at Delville Wood, Tanner was made a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) and, at the end of 1917, he was promoted temporary brigadier-general and appointed officer commanding, 8th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Division (British Army). From April 1918 until the end of the War he commanded the 1st SA Infantry Brigade, which suffered heavy casualties in the fighting that ensued. Already by the summer of 1918, 'the old regiments had shrunk to companies' (Buchan, 1920, p 216). By the end of the War, Tanner's honours included the Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (CB), the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), Officer of the Ordre de Leopold (Belgium), the Croix de Guerre (Belgium), and Chevalier of the Legion d' Honneur (France), and he was also mentioned in despatches six times (Marwick, 2014b).

A notable volunteer serviceman (ie non-career officer) of the Great War was the teenage flight-lieutenant from King Edward VII School (KES), George McCubbin, who, in 1915, had captained the school's first XI at soccer and won both cricket and athletics colours. At the end of his last term, he joined the Royal Flying Corps and, barely seven months later in 1916, he shot down the legendary German fighter ace, Oberleutnant Max Immelmann, for which he was awarded a DSO (Cartwright, 1974, p 62).

A similarly youthful airman of distinction was the Jeppestown High old boy, Fl-Lt Samuel 'Kink' Kinkead, who, with five gallantry awards (a DSO, a DSC and bar, and a DFC and bar), rivals Beauchamp-Proctor as South Africa's most decorated serviceman. He scored 33 victories during the First World War, earning his DSO in 1919 while serving in the Russian Civil War. Hailed as 'one of the finest RAF officers of his generation' (on the website of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, 1998), Kinkead was killed in March 1928, while participating as a member of the RAF Schneider Trophy team, in an attempt to raise the world air speed record to more than 300 miles (482,7 km) per hour (online Military History Journal, Volume 2 No 3, June 1972).

The 'old school'

As is apparent, thousands of these young men from South Africa's 'munition factories' did indeed heed Kettlewell's call to arms, only to perish in their droves on battlefields scattered around the globe.

While many no doubt were reluctant soldiers, it is clear from contemporary accounts that a large number of them, having been tutored in their youth in many cases by fiercely loyal schoolmasters of the Empire, embraced the opportunity to do their duty for the 'old country', Britain. As with the products of the elite schools 'at home', the bonds and allegiances of such South African boys to their old schools proved enduring and inspiring throughout the war years. Judging by the regular, personal correspondence between soldiers at the Front and their former headmasters and house-masters, the goings-on at the old school, news of the success of the First XV etc were sources of not just great interest but some solace to servicemen, far away from home and anxious for parochial news.

Not only did the teachings learned in the classrooms and on the sports fields and parade grounds of their old schools permeate much of their young lives, but sentimental thoughts of family at home and of 'the old school' became especially prominent as they drew closer to the battlefield and its deadly frontline trenches. The broad sentiments expressed in a letter received by the headmaster of Selborne College would have been repeated in letters home from many past pupils from these traditional schools: 'Very glad to hear that Selborne beat Dale at Tennis, and sorry to hear that we got the usual licking at Rugby! I do miss the good old School and the sport' (Emslie and Webster, 1976, p 150). For some old boys of these traditional schools, facing the immediate possibility of a painful death in NoMan's-Land, anxious and quite possibly terrified, they were known to often lapse into thoughts of happier times - often the carefree days of their youth. Indeed, memories of their school days were at times no doubt amongst their very final earthly thoughts. Once again, Old Etonians provide a choice example: As they advanced across No-Man's-Land in the opening moments of the Second Battle of Arras in April 1917, officers of the Household Cavalry (which was heavily populated by Old Etonians) were heard singing the Eton Boating Song, with its reference to 'jolly boating weather' (Lewis-Stempel, 2011, P 83).

Let the last word be about the iron-willed Langley, in whose often unflinching personality one finds the very embodiment of the gruff, rugger-loving, cane-wielding colonial headmaster of the early 20th century. The official Durban High School history records that even 'Madevu' was moved to tears when he heard of the deaths of the DHS boys during the War, and legend has it that he read the ever-lengthening roll in assembly with tears rolling down his cheek - and would remind the boys before him at assembly at 'School' that many of his old pupils had gone over the top to their deaths with the cheer, 'School, School, School!' on their lips.

Of this patriotic devotion, Kettlewell would no doubt have approved.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Articles and archived records

Lambert, J, "'Munition Factories ... Turning Out a Constant Supply of Living Material': White South African Elite Boys' Schools and the First World War', in South African Historical Journal, 51: 1, 2004, pp 67-86.

Loser, D, 'Commentary on the Natal Witness article, 'College Boys at the Front', Maritzburg College Archives, 2014.

Marwick, M, 'Maritzburg College's First World War roll of honour', Maritzburg College Archives, 2013.

Marwick, M (2014a), 'Contents of the Maritzburg College Honoris Causa board, updated 1 December 2014', Maritzburg College Archives.

Marwick, M (2014b), 'Notes on the life of Brig-Gen W E C Tanner, updated 1 December 2014', Maritzburg College Archives.

Internet sources

www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz [accessed 1 January 2015]: website of Auckland's First World War Heritage Trail, in which the wartime contribution of boys of Auckland Grammar School are summarised on page 36 of an online brochure.

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead [accessed 1 December 2014]: webpage of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, recording the death of Captain Wilfred Percy Nevill.

www.dovercollege.org.uklabout-us/history-of-dover-college [accessed 1 January 2015J: website of Dover College.

www.jeppeboys.co.za [accessed 1 December 2014]: website of Jeppe High School for Boys. www.obhs.school.nzlabout-us/history [accessed 1 January 2015]: website of Otago Boys' High School. www.parliament.ukledm/1997-98/950 [accessed 1 January 2015]: website of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, recording early day motion 950: 'Memorial to Flight Lieutenant S M Kinkead, RNAS/RAF', as tabled on 9 March 1998.

www.peek-01.1ivejournal.com [accessed 4 January 2015]: website of Ross Dix-Peek.

http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol023mn.html[accessed 1 January 2015]: website of the South African Military History Society, Military History Journal, Volume 2 No 3, June 1972.

www.facebook.com/thesolomonkimberley/posts/64286506 2457871 [accessed 1 January 2015]: Facebook post by S Lunderstedt titled 'Delville Wood - July 2016' and dated 18 July 2014.

Pamphlets

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, South Africa and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (Maidenhead: SA War Graves Commission, 2014).

Personal correspondence

Email received by the author on 7 November 2014 from M Guiney Esq, deputy headmaster of the South African College School, to which a photograph of the school's First World War Roll of Honour was attached.

Books

Barrett, A, Michaelhouse 1896-1968 (Balgowan: Michaelhouse Old Boys Club,1969).

Barry, S, History of Queen's College 1858-1983 (Edenvale: Mara Communications cc, 1983).

Buchan, J, The History of the South African Forces in France (London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd, 1920).

Cartwright, A, Strenue - The Story of King Edward VII School (Cape Town: Purnell & Sons,1974).

Churchill, A, Blood and Thunder - The Boys of Eton College and the First World War (London: The History Press, 2014).

Churchill, W, Great Contemporaries (London: Odhams Press Limited,1948).

Cornell, D, The History of Rondebosch Boys' High School (Cape Town: R B H S War Memorial Fund Committee, 1947).

Coyne, P, Cross of Gold - The Story of St George's Grammar School 1848-1998 (Kenilworth: Ampersand Press, 1997).

Currey, R, St Andrew's College Grahamstown 1855-1955 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell,1955).

Emslie, N and Webster, T, Bearers of the Palm (East London: Selborne Schools' History Committee, 1976).

Gardener, J, Bishops 150 - A History of the Diocesan College (Rondebosch, Cape Town: Juta & Co, 1997).

Haw, S and Frame, R, For Hearth and Home (Pietermaritzburg: MC Publications; 1988).

Jennings, H, The DHS Story 1866-1966 (Durban: Durban High School and Old Boys Memorial Trust, 1966).

Jordan, K, and McCabe, S, History of Glenwood High School 1910-2000 (Durban: Glenwood High School, 2000).

Kirkby, H, Kirkby, J and Leigh, M, Still Upon a Frontier: A History of Kingswood College, 1892-1993 (Grahamstown: Old Kingswoodian Club, 1994).

Lawson, K, Venture of Faith - The story of St John's College, Johannesburg, 1898-1968 (Johannesburg: Council of St John's College, 1968).

Lewis-Stempel, J, Six Weeks - The Short and Gallant Life of a British Officer in the First World War (London: Orion Books Limited, 2011).

Lunderstedt, S, St Patrick's Christian Brothers' College 1897-1997 (Kimberley: Christian Brothers' College, 1997).

Mcintyre, D, The Diocesan College (Cape Town: Juta & Co,1950).

Moult, L, K H Story - A History of the Kimberley Boys' High School (Kimberley: Kimberley Boys' High School Centenary Committee, 1987).

Nuttall, N, Lift Up Your Hearts - The Story of Hilton College 1872-1972 (Durban: Hayne & Gibson, 1971).

Peacock, M, Some Famous Schools in SA, Volume One - English Medium Boys' Schools (Cape Town: Longman Southern Africa, 1972).

Seldon, A and Walsh, D, Public Schools and the Great War (London: Pen & Sword Military, 2013).

Stevens, T, The Time of Our Lives - St Andrew's College 1855-1990 (Cape Town: Creda Press, 1990).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org