The South African

The South African

By Dr Anne Samson, Independent Historian, Co-ordinator Great War in Africa Association

Biographical note: Anne completed her BA degree at UNISA in 1996, her MA in Twentieth Century Historical Studies in 1998 at the University of Westminster, London and her PhD in 2004 at the University of Royal Holloway, London. She is the author of two books on South Africa's involvement in Africa in the First World War and numerous articles on related topics.

South Africa entered the First World War when Britain's ultimatum to Germany expired. This was the price of belonging to the Empire and would result in a turbulent four years for the Union as pro-Empire and anti-British political forces relived the tense years of the 1899-1902 war where Boer had fought against Brit.

Before war broke out on 4 August 1914, Prime Minister Louis Botha was returning to South Africa from a visit to Rhodesia. The plan had been to return to South Africa by German boat from Beira. However, having been warned of the imminent outbreak of war by David Graaff, the South African government representative in London, Botha returned overland, thereby denying the Germans a high status prisoner of war (Buxton, 1924, p 336), a situation which would have left the South African government with even greater challenges than it already had to face.

On 7 August the British government telegrammed, asking the South African government to put the wireless stations in German South West Africa out of action. When the cabinet met, it agreed that Britain could withdraw the Imperial Garrison troops except for one regiment which would remain at the Castle in Cape Town. However, the cabinet was divided over the request to destroy the wireless stations in South West Africa. Botha wanted to go further than the British request and subjugate the whole of the Germany colony in line with what he had told David Lloyd George, then British Chancellor of the Exchequer, in 1911. Opposing Botha's idea was F S Malan, who felt that any unprovoked attack on German South West Africa would re-open wounds from the 1899-1902 war. He had no problem with South Africa defending itself, but strongly objected to launching an attack. After an intense discussion, Botha won his dissenters over by pointing out that if South Africa did not undertake the operation there was nothing to stop Britain from asking Australia or India to do so. This was enough to swing the vote. However, nothing could be done until Parliament sanctioned the use of the armed forces outside the Union's borders. This would only happen in September, when the new Governor-General and High Commissioner for South Africa, Sydney Charles Buxton, arrived to take up his post.

Buxton was due to arrive on 7 September 1914 and pending his arrival, South Africa was under the watchful eye of Acting Governor-General, Sir H de Villiers, Chief Justice, and Colonel Wolfe Murray as High Commissioner responsible for the two British South Africa Company chartered territories of Southern and Northern Rhodesia, the three protectorates of Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland, and the Imperial Garrison force. Three days before Buxton arrived, de Villiers died and his position as Acting Governor-General was filled by the Attorney-General, Sir James Rose Innes. In some ways, de Villiers' death had no impact on the situation as he, and later Rose Innes, had refused to advise the government on political issues. This was not surprising as they were South African and very aware of the different feelings amongst the population. Any advice they gave could be misconstrued and impact on their professional roles. Little communication took place between de Villiers and Wolfe Murray as they were in different parts of the country and not aware that the communications from London were to be shared. When the Imperial Garrison troops left South Africa, Wolfe Murray left with them. What Buxton did lose out on was the record de Villiers kept as this took until his estate was sorted to get to Buxton and little is recorded of communications between Buxton and Wolfe Murray.

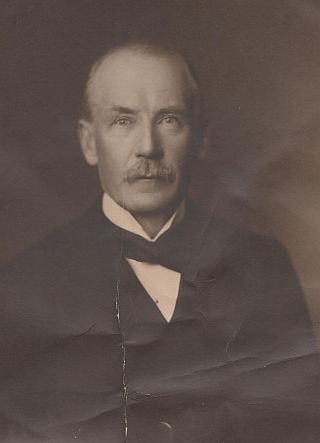

Nevertheless, preparations for war continued with the Minister of War, Jan Smuts, and his civilian administrator, HRM Bourne. Meetings were held between the heads of the various forces making up the Union Defence Force and plans were drawn up for the invasion of German South West Africa. Smuts and Botha were aware of dissension but believed they could overcome it with reason. This they failed to do as was noted after Parliament met and voted on 8 and 9 September with the Senate ratifying the decision on 14 September. Sir George Farrar, Member for Parliament and owner of ERPM noted: 'I think that if ever a man has played the game for the British Empire this time it has been Botha, and he has fairly burnt his boats with his own people. They expected the usual opposition from Hertzog, but I think he had great trouble with his own people. [ ... ] At the bottom of it all was personal hatred of Botha. [ ... ] Anyhow on the division he only got 12 supporters and it went through.' (Farrar papers 12/1, 20 Sep 1914).

One of the debates about whether South Africa was justified in going to war against the German colony involved the German invasion at Nakob on the border between the Union and German South West Africa. Smuts claimed that the Germans had entered the Union at Nakob on 19 August 1914, whilst Hertzog claimed that Smuts had altered the border on the map to prove his point. In reality, the border had not been clearly marked when the Act of Union was drawn up as the expectation or hope was that the Union's borders would change (Samson, 2013, p 74).

On 15 September 1914, having returned to Johannesburg after the Parliamentary sitting in which he did not vote, Koos de la Rey was accidentally killed when he and General CF Beyers went through a road block set to capture the infamous Foster Gang which had earlier been on the rampage in Boksburg. De la Rey who had been told by his prophet, Siener van Rensburg, that 'the 15th' would be significant, thought he was doing the right thing to bring about South African independence from the British Empire. On previous occasions Botha and Smuts had been able to sway him from the task Beyers and others had set for him by sending Abe Bailey as companion to the old Boer General, but on this occasion, Bailey was not available (Samson, 2006, p 84). On hearing of de la Rey's death whilst playing golf with the Governor-General in Cape Town, Botha left immediately for Johannesburg, Buxton following the next day. De la Rey's funeral was the last time Botha and Beyers were to meet in peace (Samson, 2013, p 73).

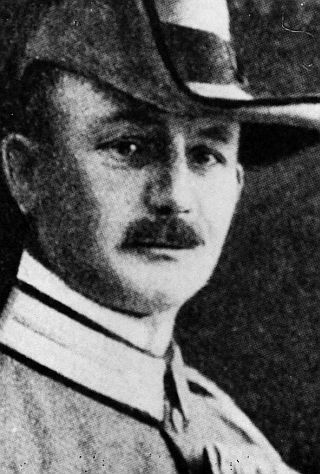

Soon after, when the forces were ready to entrain, Beyers resigned his post, soldiers refused to entrain and rebellion erupted. SG 'Manie' Maritz, who was ordered into German South West Africa, took his forces with him and, on arrival in the German colony, took prisoner those men who refused to oppose Britain, including Deneys Reitz's brother (Calitz, 2008). Maritz had entered into an agreement with the German colonial officials to side with them and ensure the Union's independence.

Meanwhile, the Governor-General was QUsy assisting the Union government with its invasion plans for German South West Africa. By 1 October, he had accepted the offer of the British South Africa Company to use the 500-man 1st Rhodesian Regiment, which the company had raised back in August. However rather than this force go to Europe as intended, they were sent to serve in South West Africa. On route, they were directed to Bloemfontein in case Botha needed their assistance against the rebels. Botha was prepared to accept the Rhodesians, but turned down Britain's offer to divert a ship carrying Australians to support him (Samson, 2013, pp 57,75). Botha felt it was important that South Africa sort out its own troubles and, as the hope was for the Rhodesias to join the Union when the charter expired, using their services in this crisis time was justified.

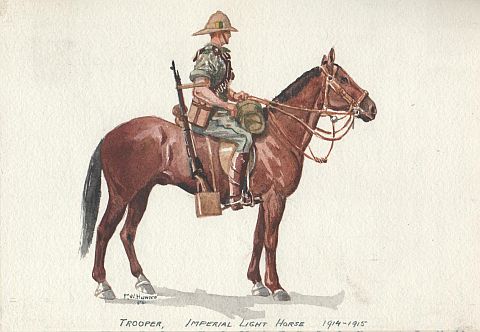

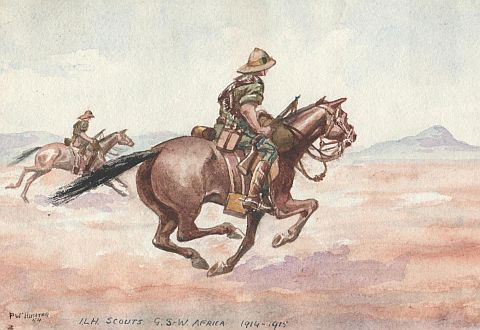

By December, the rebellion had been brought to an end and preparations could begin again for continuing the invasion of South West Africa. The port towns of Swakopmund and Lüderitzbucht had fallen into South African hands following coastal attacks on 18 and 19 September 1914, but South Africans had been defeated by the Germans along the border at Sandfontein (van der Waag, 2013). On Christmas Day 1914, the campaign began once more. In February 1915, Louis Botha took to the field as commander of the forces, believing that he was the only person who could bring together the white English and Afrikaans troops. Botha had, before taking to the field, reworked the plans to allow for a multi-pronged invasion. He led the main Northern force and out of six months' campaign, saw action for only 24 days. Botha's move across the desert was aided by the work of the engineers, including the support of mining magnates such as Thomas Cullinan, who was involved in water supplies, and George Farrar, who assisted with railways (Samson, 2012). From April 1915, Jan Smuts, too, took to the field leading the Southern Command.

The South West Africa campaign was a new experience for most of the participating Union forces. For the Afrikaners, they were fighting outside their local territory and could not live off the land as they had during the 1899-1902 war. Motor vehicles were used to transport equipment and men, making it more mobile than relying purely on horses, although the desert sand provided its own challenge. The British or English component of the South African forces were under non-British generals who did not fully understand the peculiarities of British command and both groups had to cope with aeroplanes for the first time in combat. As Farrar explained to his wife who was in England, one morning, a German plane dropped two bombs on the camp - he was fifty yards away: 'One good thing was they put a parachute on, and you could see the bomb drop.' It killed one man and injured another nine. The following day another came and then not again. 'I don't think they will worry us much more, because they have only two aeroplanes and they can't afford to lose one' (Farrar papers 12/1, 3 Jan 1915).

Whilst the campaign in South West was underway, a rebellion erupted in Nyasaland led by the independent black missionary, John Chilembwe. The local volunteer and Imperial forces in the protectorate under Governor George Smith brought the rebellion under control during January and February 1915, but the potential for future unrest meant that there was a military shortage. Therefore, to assist the Nyasaland Volunteer Reserve and King's African Rifles, two hundred South Africans went north (Samson, 2013, p 39). They were later subsumed into the Field Force led by General Edward Northey from November 1915. South Africans were also to serve as reinforcements for the Rhodesian forces when the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment was sent to East Africa in 1915. It was felt that this contingent of 500 men could not be sent to Europe before the 1st Regiment as that would cause upset.

In July 1915, the campaign in South West Africa came to an end when German Governor Seitz signed the surrender documents. Louis Botha, although Prime Minister and commander in chief, insisted on sending the terms to Pretoria for acceptance before the final document was signed. For the remainder of the war, the German colony was administered by the South African government, which started to construct an infrastructure which was compatible with that in the Union.

As it was becoming clear that the campaign was drawing to an end, there was some discussion as to what should happen to the Union forces. The options were to send them to Europe or to find some other theatre, such as East Africa, in which the men could serve. However, Botha was reluctant to commit the South Africans to any further military action until after the scheduled election had taken place later in the year. The result was that many of the English speaking South Africans who had fought in South West, left for England of their own accord once they were demobilised. As this became known to Smuts, he was able to introduce a system whereby men could sign up for service in East Africa for when that option became available.

Discussions with London over sending South Africans to East Africa began in April 1915 . Buxton had been approached by both Smuts and Senator JX Merriman about this and there had been a letter in one of the newspapers calling for South Africans to go to East Africa. The authorities in London were divided over whether to re-launch the campaign in East Africa and whether to use South Africans. Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, asked for mounted troops from the Union to serve on the Western Front and saw no reason for reactivating the East African theatre. He was opposed by his General Staff and the politicians who saw an opportunity for gaining a German territory they had long desired and for which there was an outlet for South Africans who would not fight in Europe. This latter point had been raised by Smuts who recognised that there was a group of South Africans prepared to protect the Union but not openly support the British Empire. East Africa would provide the solution to this dilemma as, if all the Union's expansionist plans came to fruition, German East Africa would eventually border the Union (Samson, 2013, pp 80-94).

The South African election was held in October 1915. In November, the first forces for East Africa began to be recruited. During the discussions around the forces, it materialised that the South Africans had miscalculated the need for reinforcements with the result that they would not be able to take complete control of the East African theatre in the same way they had South West (Samson, 2013, p 94). Another issue was the payment of the troops and the supply of equipment, to which the Nationalist Party objected as this was money which would, in their opinion, be better spent in South Africa on South Africans. In order to avoid a political crisis, especially as Botha had a small majority and was relying on Unionist Party support to remain in power, it was agreed that Britain would fund the South African contingents for East Africa and Europe. This meant that the forces were Imperial troops and technically out of the control of the Union (Samson, 2013, pp 94-95).

The choice of commander of the East African force to lead the South Africans fell to Sir General Horace Smith-Dorrien who had won the respect of the Boers during the 1899-1902 war and who was well regarded by the British forces despite having lost his command in Europe due to a personal conflict with Lord French. En route to South Africa, Smith-Dorrien fell ill and, although much improved, was still not well enough to travel on arrival in Cape Town. He remained in Cape Town whilst his secretary travelled to Pretoria to liaise with the military officials there. Smuts, supported by Buxton, felt that the delay of a month which is what Smith-Dorrien felt he would need in. order to fully recover, was unacceptable and proposed that he, Smuts, should lead the forces. Smuts had been an option in October/November when the discussions were taking place in London but it was felt he was needed more in South Africa which was in a volatile political position. By January 1916, it was felt the Union was sufficiently stable to allow him to leave (Buxton, 1924, pp 293-295). On 5 February 1916, London approved his appointment and he followed after the troops, arriving in East Africa on 19 February, the week after the South Africans were repulsed at the Battle of Salaita Hill.

This defeat, although severe, served Smuts well politically as he had had no input into the battle plan which had been drawn up by Smith-Dorrien, based on his knowledge of the fighting on the Western Front, and approved by General 'Wully' Robertson on his first day as Chief, Imperial General Staff (Samson, 2013, p 111). Smuts used the opportunity to introduce the encircling tactic, rearrange his forces and have South Africans appointed to the General Staff. The defeat was also to prove a significant lesson for the overconfident South Africans, who were shown how to fight by the Indian troops, who had fled during the battle of Tanga in November 1914.

Smuts led the troops in East Africa until January 1917 when he was asked to attend the Imperial meetings in London which David Lloyd George, the new Prime Minister of Britain, had called. Smuts was replaced by General Reginald Hoskins who had been Inspector General of the King's African Rifles in East Africa prior to the outbreak of war. However, Hoskins was only to serve five months as commander before he was replaced by South African General Jaap van Deventer in a move likely orchestrated by Smuts (Samson, 2013, p 136). Van Deventer was provided with reinforcements from South Africa which Botha had previously denied Hoskins and was to see the campaign through to its end on 25 November 1918 when the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered as instructed by the terms of the European Armistice.

During this time, the predominantly English speakIng forces under the command of General Tim Lukin, went to Europe via Egypt where they excelled themselves on both fronts. Following their decimation at Delville Wood the South Africans continued to serve in Europe in various capacities. Others who had been invalided back from East Africa at the time Smuts left, joined the forces for service in Palestine (another theatre which needs researching).

Finally, the First World War in Africa is often regarded as a 'white man's war'. However, the South African forces in all theatres of war consisted of more than white men. Although the majority of the armed forces were white, there were two corps of Cape coloureds who served in East Africa, Indians who served as stretcher bearers and blacks who served as labourers, railway men, drivers, mechanics and porters. All, working together, constituted South Africa's war effort. The home front, too, played its role in supporting base camps in Pietermaritzburg, Potchefstroom and Cape Town, while the women were involved in organising comforts for the men and moving into factories to release men for the front.

References

Buxton, Earl, General Botha (London, 1924)

Calitz, GJ, 'Deneys Reitz (1882-1944), Krygsman, avonturier en politikus (Thesis, University of Pretoria, 2008)

Farrar papers, Rhodes House Library, Oxford, United Kingdom

Samson, A, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign, 1914-1918: The Union comes of age (London, IB Tauris, 2006)

Samson, A, 'Mining magnates and the First World War' (paper presented at Brenthurst Library November 2012· available academica.edu)

Samson, A, World War One in Africa: The forgotten conflict of the European powers London IB Tauris 2013)

Van der Waag, I, 'The battle of Sandfontein, 26 September 1914: South African military reform and the German South-West Africa Campaign, 1914-1918' in First World War Studies Vol 4 No 2, 2013

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org