The South African

The South African

BACKGROUND

My dad was a sergeant-pharmacist in the South African Medical Corps and was first stationed at Baragwanath Military Hospital to the south-west of Johannesburg. In 1942 he was transferred to Snell Parade Military Base in Durban and, while he was there, he also served at the Sick Bay on the Bluff before being shipped 'Up North' to the Middle East a year or so later. My mother and I lived in a residential hotel on the Esplanade during this time and I attended Addington School, on South Beach, close to the harbour. My classmates and I were acutely aware of the War, because we had air-raid practice once a day, every day. This was brought about by the fact that a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft had flown over Durban during 1942.

Observations of Durban Harbour

Mules were required for the Allied forces in Burma and hundreds, if not thousands, of these animals were accumulated in an animal kraal situated at Stamford Hill in Durban. These animals were regularly herded to the harbour along Marine Parade and South Beach, past our school. They were loaded onto ships in the harbour and these vessels set sail for Burma. Unfortunately, due to U-boat activity off the South African coast, many of those mules went down to the bottom - on several occasions not too far off Durban. The situation became dire when more mules went down with their ships to the bottom of the sea than managed to get through to the Far East. Eventually, a fast ship by the name of Silandia was brought to Durban to transport the animals to Burma. The Silandia could outrun the U-boats and the problem was largely solved - the mules intended for Burma were finally getting through!

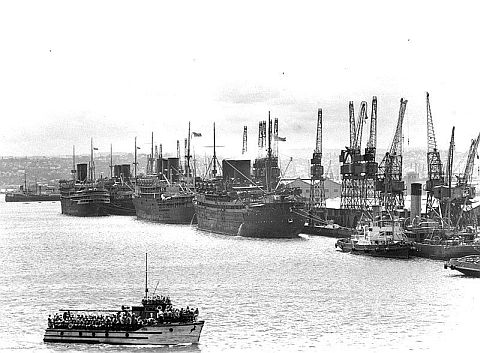

Allied convoys would often call at Durban en route to the Middle East and other theatres of war. It was too risky to allow the vessels to drop anchor in the roadstead off Durban, so the ships were all admitted to the Port and banked in multiples at each berth in the harbour. Seeing these troopships in their drab grey paint was quite a sight. We were not allowed into the restricted harbour areas during the War, but it was easy to see the ships standing tall behind the sheds on the quayside.

The exception to the drab grey troopships and naval vessels was the regular appearance of hospital ships and, in particular, the Oranje, Tjijalengka, and Amra were frequent visitors. As hospital ships, these vessels were painted overall white with a wide green band running the length of the hull with a large red cross amidships and slightly smaller red crosses at the bow and stern. These ships brought battle-scarred patients down to South Africa for treatment of their wounds in military hospitals, notably at Oribi, near Pietermaritzburg. They also conveyed mainly British soldiers who had contracted tuberculosis in the Western Desert campaign. The latter were transported by South African Railways' hospital trains from the quayside to Baragwanath Hospital near Johannesburg.

My dad went 'up North' on the Amra and, although she was supposed to be protected by the Geneva Convention, she still had periods at sea when all the lights were switched off due to the presence of German and Japanese submarines in the area.

The Royal Navy also visited Durban regularly during the War. In the early 1940s, HMS Nelson, that great battleship with three triple 16-inch gun turrets all mounted ahead of her bridge, called in at Durban with several other notable ships like the aircraft carrier, HMS Eagle. When the Nelson entered the harbour, I was told that she only had a couple of inches to spare between her keel and the seabed.

The Bluff, overlooking Durban Harbour, bristled with heavy-calibre gun batteries to defend the Port in case of enemy action. The gun crews were given gunnery practice on a regular basis and, to this end, a South African Railways & Harbours tug would tow a target off-shore between Umhlanga to the north of Durban and Umbogintwini to the south. The target was mounted on a barge towed by the tug and we would hear the big guns' 'boom' as they fired their rounds.

Durban also had air defence units on regular patrols along the coast. The aircraft used were flying-boats, American Catalinas and the bigger British Sunderlands. These craft used to take off and land on the Maydon Channel and I would be fascinated watching them go about their business from my residential hotel balcony overlooking Dick King's horse statue at the bottom of Gardiner Street. There was a large warehouse opposite my school at Addington, where spare Catalinas were stored, with their wings in separate cradles. On the odd occasion, I would see a military lorry haul a new Catalina out of the storehouse and set off for the harbour.

The wonderful fleet of South African Railways & Harbours' tugs based in Durban included the Sir William Hoy, which, in her prime, was one of the most powerful tugs of her type in the world; the Sir David Hunter, with her distinctive twin funnels; and the T Eriksen, Otto Siedle, Ulundi and E S Steytler. These were all ocean-going salvage tugs which the South African Railways' administration used as harbour tugs, enabling them to offer coastal salvage services when required. During the War, all the tugs had plain yellow funnels - the green stripes being added sometime in 1946.

Royal Navy warships of all descriptions were also dry-docked for refitting during the War. I particularly remember HMS Sussex spending three months in dry dock up at Bayhead, because a serving chief petty officer on shore leave during that time would meet an aunt of mine - he eventually became an uncle of mine after the War. Seeing a ship in the roadstead outside Durban, I once ran into my mother's bedroom and exclaimed that the Queen Mary was anchored off Durban! I later discovered my mistaken identity when I purchased the book, Ile de France, by Don Stanford, which confirmed the French ship's visit to Durban during the war at that time. I am aware of the Queen Mary calling at Cape Town during the War, but I can't be certain that she called at Durban. She may have, in which case it re-opens my personal sighting but, unless proven otherwise, I have no reason to doubt that the ship that I saw was in fact the Ile de France.

The harbour entrance was also protected by gun batteries and a heavy, interlocked chain that was drawn across the harbour mouth to prevent a submarine from entering below the surface. In Durban, the slogan, 'Zip your Lips about Ships' was taken very seriously. Not all South Africans regarded Germany as the enemy, however. There was a German fellow by the name of 'Zunkel' living in Pietermaritzburg who fed Germany with shipping information using a secret radio transmitter.

Durban also had a black-out in place during the War. Curiously, it was started in haste by none other than HMS Warspite, another Queen Elizabeth Class battleship of the Royal Navy. When HMS Warspite arrived off Durban one evening in the early 1940s, the beachfront was ablaze with lights. I learned later that the Vice-Admiral on board the Warspite radioed the Bluff and said, 'Tell Durban Corporation to switch off their bloody lights! My ship is a sitting target silhouetted against this blaze from the light on-shore!' The lights were promptly turned off and, from that time on, we had a full black-out in force in Durban. The Corporation even stopped running trolleybuses to Marine Parade and South Beach to avoid arcing trolley poles at junctions in the wires being seen out to sea. We had diesel buses that I used to get to and from school. All buildings facing the sea had to install heavy curtaining and all cars had cowls fitted to their head-lights. I don't know how visitors' cars were treated, but I assume that they were not permitted near the beach at night.

Addendum: Notes by J M Parkinson, Military History Society, on Les Pivnic's collection of Second World War photographs of Durban Harbour

These really splendid photographs serve to vividly remind us all of those extraordinary days when Allied forces, including much South African assistance, were so desperately involved in East and especially North Africa, but also India and a tidy little operation in Vichy-held Madagascar.

Briefly, following the fall of France in June 1940, there was a real prospect of a subsequent Nazi attempt to invade Britain. Fortunately, later during that year, it became clear that no such attempt would be made, so, increasingly, military units could be released for activity in "other theatres. Also in June 1940, Italy had entered the war, with her African Empire, which included Libya in North Africa, and Somalia and Ethiopia in East Africa. For both the Allies and the Axis, it was necessary to ensure that the oil producing territories in the Middle East did not come under either enemy influence or occupation. Clearly the Suez Canal was a vital thoroughfare.

Usually war-time convoys were designated with code letters and a number, the code letters referring to the relevant port(s) of origin and destination. In this instance convoys transporting military reinforcements to the Middle East, and of necessity steaming around the Cape, generallywere assigned the code letters'WS', followed by a number. The initials'WS' were those of the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. Thus there was always a certain panache attached to these extremely important ship movements. Not only that, but taking the example of the first such convoy, 'WS.1' which left Liverpool and the Clyde on 29 June 1940, this consisted of three huge vessels then well known throughout the British Empire. They were all Cunard passenger liners, namely Aquitania, Mauretania and Queen Mary

The merchant ships of these convoys were escorted by Allied warships, usually cruisers such as Sussex, but on occasion inluding battleships and even aircraft carrier such as those also shown here, and Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMC), the latter being merchantmen taken up for war service and lightly armed. A number of these 'WS' movements consisted of so many ships that, as they rounded the Cape in South Africa, it was necessary to divide them, with some calling at Cape Town and others at Durban.

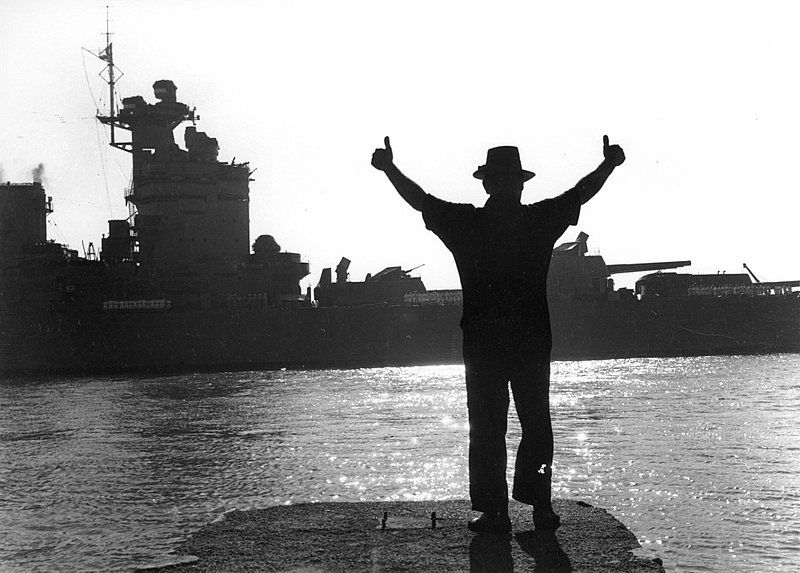

The photograph above is a good example of an AMC, complete with lightly armoured bridge superstructure, being escorted into Durban. The first photograph in this article, similarly is an excellent example of such troopships with several being double banked, at berths in Durban. Clearly, in time of war, the risk could not be taken to permit such important ships to lie at anchor outside the port.

The photograph above is of the Dutch motor (as opposed to steam powered) passenger liner Oranje, built in 1939 and intended for the service to their possessions in the East Indies. Early in 1941 at Sydney, NSW, she was converted for wartime service as a hospital ship in which role she is seen here, in colour painted white, also bearing huge Red Cross emblems. Some South Africans may remember her between the late 1960s and the mid-1970s, when, as Angelina Lauro, she called at South African ports while engaged on her regular run between the Mediterranean and Australia.

In December 1941, after Japan entered the Second World War, added emphasis was given to the movement of troops and material around the Cape. For instance, although Malaya would be lost, it was vital that India be defended adequately.

At the time, just off the east coast of Africa, the large island of Madagascar, with the harbour of Diego Suarez situated in the north, was held by Vichy France. Fearing that just possibly Japan might be interested in coming to an agreement with Vichy and in establishing herself at Diego Suarez, the Allies resolved to occupy that important port. With naval operations under the command of the South African-born Royal Naval officer, Rear-Admiral Edward Neville Syfret, in May 1942, the appropriate landings took place. Known as Operation 'lronclad', one of the Royal Naval vessels to participate was the battleship Ramilles. The photograph seen at top left on p84 is not of Warspite but appears to be of one of five of the 'R' class, possibly Ramilles herself at the time when she was involved in this successful affair. However the cowl on her funnel indicates a later modification. Censorship in wartime will not have made it easy for all ships always to be identified correctly. (According to Mr Pivnic the photograph negative was captioned Warspite and might thus represent the ship after a major rebuild which gave her an appearance very similar to that of an 'R' Class battleship, but concedes that Mr Parkinson may be correct -Ed).

The editors, together with the Cape Town branch of our Society, are to be congratulated on obtaining such historically significant photographs for inclusion in this issue of our Journal.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org