The South African

The South African

On 12 April 1862, shot and shell flew over the waters of Charleston harbour as the South Carolina Militia bombarded the Federal arsenal known as Fort Sumter on an island in the harbour. The United States of America, having just inaugurated a new President, was facing an armed insurrection by one of its constituent States. South Carolina, already joined by several other Southern States, with others in the wings, was quite prepared, indeed was eager, to wage war for autonomy of the new Confederacy. It was in a way a unique manner for a war to commence as no invading force had crossed any border. But water, salt or fresh, was destined to be of major importance if the United States of America was to crush this rebellion of eleven Southern States. Control of ports, harbours, rivers and waterways was to play a key role.

The Blockade of the South

Several times previously, as the emancipation movements sought to have slavery outlawed, threats by Southern States to secede from the Union had been made and, in the late 1850s, the vociferous call for emancipation was again being heard. A restless political climate in 1859 and 1860 resulted in the election of Abraham Lincoln as President. He was a champion of emancipation and this fact brought matters to a head. On the day he was elected, months even before he swore the Oath of Office in February 1861, the State of South Carolina had passed a resolution of secession, followed soon afterwards by several other States.

This very act of secession was the challenge now facing the United States: How could the Union face this act of open rebellion? Since the bellicose threats of secession during the 1840s, an idea conceived by General Winfield Scott had mouldered in the US Department of Defence's archives; this was the so-called 'Anaconda Plan'. Derided by several leading politicians and the press at the time, this plan envisaged a strangulation of the Southern States by blockading the coastal inlets and ports and seizing every strategic point on the huge Mississippi-Ohio River system.

The secessionist movement pitted the traditionally slave-owning States, except for Kentucky and Maryland, against the so-called 'free' States. In real terms this was a disproportionate contest as these Northern States, the 'Union', had more than twice the population of the South! The Union also possessed 90% of all industrial potential and the greater portion of the country's 30 000 mile (48 270 km) railway system. In contrast, more than 70% of all American export value came from the Southern States, mainly in the form of cotton. This soon came to be called 'King Cotton' as rhetoric grew in Europe and in the South's propaganda. Other major money earners were rice, sugar and tobacco.

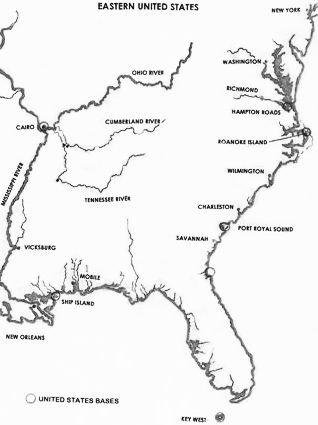

In order to keep this thriving and lucrative trade viable, the South's population of a mere nine million, which included no less than 3,6 million slaves, had its work cut out. Exports left the South for Europe and the North through ten major ports along a coastline stretching from Virginia to Texas for some 3 500 miles (4 800 km). In addition, there were an estimated 180 inlets, bays and river mouths which were navigable by smaller vessels and were indeed used in a busy coastal trade.

The Mississippi and Ohio rivers formed a huge water highway stretching from the Gulf of Mexico as far as Pittsburgh for just on 1 900 miles (3 050 km) and, had the State of Kentucky seceded, the Ohio would in fact have been the South's northernmost border.

If the Anaconda Plan was to succeed, control would have to be imposed firstly on the long coastline, and use of the Mississippi would have to be denied to the Rebels. In addition, the invasion of the South and defeat of the Rebels on the ground was obligatory for the North.

Key to denying the Confederacy the use of its cotton exports to finance the rebellion was, of course, the controversial decision by Abraham Lincoln to declare a blockade. This was controversial because, by doing so, he gave legitimacy to both the Confederacy's point of view as well as sympathetic sections of government in Europe and Great Britain. It was, in fact, tacit recognition of the Confederacy as a nation in the eyes of international law.

For a blockade to succeed it is necessary to deny all vessels use of the ports and harbours of the target nation, but how was it to be enforced in this instance? On 12 April 1861, the United States Navy had just 90 vessels on its inventory. A mere 40 of those were in commission and of those, more than half were on foreign stations protecting America's trade interests. By the same token, the Confederate States' Navy existed merely on paper, although much preliminary work was being done. In terms of numbers, the US Navy had some 1 500 officers and 7 500 seamen. However, some 400 officers elected to give their allegiance to the Confederacy, although proportionately the loss of seamen was minimal.

Both the opposing navies had the services of some dynamic men. The US Navy, under its Secretary, Gideon Welles, assisted by Gustavus A Fox, the Under-Secretary, immediately initiated a ship-building programme which ultimately should have warned Japan 82 years later of the awesome industrial might of the United States. By December 1861, the Navy was able to deploy 260 ships on blockade duty. Commandeering, chartering and buying of virtually any seaworthy vessels of suitable size supplied the means, even if it meant using a number of sailing ships. A plus was the patriotic fervour amongst merchant seamen and retired navy personnel which saw to the crewing of these vessels. Side-wheel ferry and packet-boats were pressed into service, many un-armed, but nevertheless capable of signalling armed screw-driven vessels to intercept blockade runners.

The Confederacy, with very few facilities and a governing infrastructure which was subject to interstate squabbling, nevertheless had the services of men such as Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan, Commanders James D Bulloch, Raphael Semmes and Navy Secretary, Stephen R Mallory. These men were giants of organisation, deception and subterfuge. Bulloch, especially, was to play a significant part in growing the capability of the Confederate response to the Union's massive fleet build-up.

Lincoln's proclamation of the blockade on 19 April was half anticipated by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who, on 17 April, issued 'Letters of Marque' to any Southern ship-owners who wished to take up the offer. By the middle of July 1861, some twenty of these modern day privateers were operating against Yankee merchant shipping in the North Atlantic and had captured about two dozen prizes. A howl of protest and panic from Northern merchants initiated the US Navy's first sea-going operations and, by the end of the year, all the privateers had either been apprehended or had quietly retired from the trade. Many were the legal ramifications, threats and counterthreats before the practice died down. Actually, the blockade was effective enough to prohibit the privateers from bringing their prizes into Southern ports in order to benefit the Confederacy. Neutral nations also cold-shouldered them, fearing consequences which were never stated.

A primary response by the Rebels to the Union's need to wage war was to try to interdict whatever exports and imports the Union required for viability and a key Confederate Navy plan was to commission and send commerce raiders onto the high seas. In mid-June 1861 the first of these, the little CSS Sumter, a five-gun Sloop-of-War, hastily converted from service as a mail-packet, slipped past the blockading ships off the mouth of the Mississippi under the command of Raphael Semmes. During the next six months she captured or burned eighteen merchant vessels before Union warships bottled her up in Gibraltar. Semmes had commenced his career as the nemesis of the Union's merchant marine!

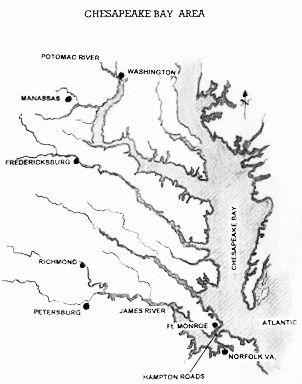

For the United States Navy, problems of keeping the blockading ships on station were mounting. Vessels were often spending as much time, if not more in certain instances, sailing to or from base for replenishing of coal, water and supplies, as they were being on patrol. With only the naval bases at Key West, Florida, and at Hampton Roads in Chesapeake Bay available, plans were put into action using combined operations between the War Department and the Navy to secure other bases.

The first of these operations, in August 1861, was the seizing of Hatteras Inlet on the outer banks of North Carolina. Despite the prevailing belief that wooden ships could not overcome well built shore installations, the combination of manoeuvrable screw-driven vessels and modern armament saw the Rebels losing control of the inlet after a bombardment pounded the forts built there into submission. Some 5 000 soldiers were landed and the Rebels soon surrendered. This gave the United States Navy access into the sheltered waters of Pamlico Sound and the means to create a forward base. The waters of both this Sound and its adjacent body of water, Albamarle Sound, were the key to Richmond's back door and the Navy soon started bottling up the many inlets and ports. In November, a massive operation against fixed defences at Port Royal, Georgia, which involved no fewer than 75 vessels, gave the Navy another safe natural harbour which was second in importance only to Hampton Roads. By June 1862 the Union Navy only had two major ports not bottled up: Charleston SC and Wilmington North Carolina on the Cape Fear River, which, in fact, remained open until virtually the end of the war. Mobile, Alabama, was also to prove a difficult port to bottle up and was used by blockade-running vessels well into 1864.

Another plum which fell into Union hands was Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico, which for some mysterious reason was abandoned by the Confederate defenders after a token shelling of the island by the heavy frigate USS Minnesota. This brought about not only a major support base for the blockading ships but also a facility to build up the attacking fleet for the successful attack on New Orleans in April 1862. Later, in August 1864, the operation to seize Mobile was mounted from Ship Island.

It can safely be said that the many successful operations in seizing not only the bases described above, but also others similar in vein, were a morale boost for the Union. During that first year of the war when several planned successes on land went horribly wrong and as the casualty lists grew longer and longer, the Navy achieved wonders which lifted sagging Union hopes for victory.

Combined operations

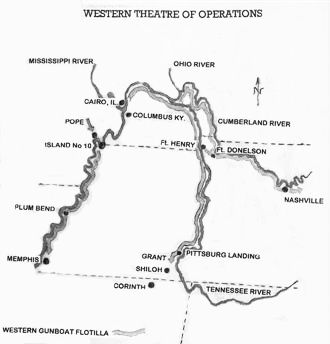

After the commencement of hostilities it had become apparent that the inevitable invasion of the South's territory would in all likelihood commence in the Western Theatre. In the vast Mississippi Basin, the United States Army departments of Missouri and Ohio were confronted by a 500 mile (804,5 km) long Confederate defence line stretching from the Ozarks in Arkansas across the Mississippi through Kentucky, ending near the Appalachians in West Virginia. Although the other theatre, in the East where Washington DC faced the Rebels across the Potomac in Northern Virginia, was most attractive to the Union's planners, it was imperative initially to consolidate the defence of the Capital. Maryland, which surrounds the Federal capital, and which had a population with divided loyalties, had demonstrated its neutrality as an alternative to becoming a war zone. An unsuccessful Union campaign to advance on and capture the Conservative capital of Richmond a mere hundred miles away had already seen Federal noses bloodied at Manassas (Bull Run) in July 1861 and the Union was licking its wounds after this battle and two others, one at Wilson's Creek further west and several skirmishes with Johnson's Army of Tennessee in Kentucky which defended the South's Western Theatre.

By the end of November 1861, Abraham Lincoln was becoming increasingly frustrated by the reluctance of his generals to attack the Confederates. Both Halleck, commanding at Cairo, Illinois on the Mississippi, and McClelland in Washington were dragging their feet, each obsessed with the belief that their armies were not strong enough, although generally it was known that Union recruitment and training had already created sufficient forces. Lincoln firmly believed, correctly as history has shown, that simultaneous attacks on the South at widely separated points could not be withstood. This was a quite reasonable belief when taking into account the serious deficits in numbers under arms and the North's considerable superiority in heavy weapons, railway infrastructure and a fast-growing Navy which would have a major affect on the South's abilities to counter them.

Eventually, a new alliance of minds within Halleck's command, Brigadier-General Ulysses S Grant and the Navy's Flag Officer, Andrew H Foote, came forward with definite plans. The Rebel defences in Kentucky could be pierced, they said, and the go-ahead was given.

These two men, Grant with his no-nonsense aggressive approach to warfare and Foote, a well trained naval officer, had the means to deploy water and land combined operations. Foote had been sent by the Navy to advise the Army about river-borne operations as the War Department had decreed from the beginning that the Army would have to take care of its own requirements in terms of moving troops, deploying and supporting them. He arrived shortly after a series of fortuitous decisions had been made.

A new type of gunboat

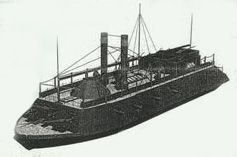

Early in the war a St Louis boatyard owner, James B Eades, had approached the army command at Cairo with a proposal to convert a large river salvage vessel into an ironclad gunboat to assist in operations along the Mississippi. Foote, a naval tactician, had fortunately been preceded by a Commander John Rodgers to whom Eades was referred. Although Rodgers had not agreed with Eades' first ideas, the pair quickly worked out a solution for building urgently needed specialist gunboats. Eades brought riverboat knowledge and Rodgers the fighting and crewing requirements, but it was only when the design team was augmented by a marine architect called Samuel M Pook that matters really gelled and a truly unique vessel emerged from the drawing board.

This was the 'City' Class of ironclad gunboat, seven of which were built under Eades' supervision in various boat yards in and around St Louis. Displacing 512 tonnes and drawing a mere six feet of water, they were stern wheel paddle steamers with armour-plated casemates of unique design resembling a barn roof and were soon called 'Pook's Turtles' by the rivermen. They were heavily armed, carrying thirteen guns apiece and, although batteries differed slightly, these featured 42 and 64 pounders as well as 8-inch rifles. Truly formidable vessels, Eades had completed all the boats by mid-January 1862.

Although the strategic value of the rivers in the area, particularly the lower Ohio, the Cumberland and the Tennessee, had been assessed, very little action had taken place. Both sides had immediately set about converting riverboats into warships of some sort even if it meant placing field pieces behind a casemate of sandbags on the foredeck, but they were very frail and amateurish. The Pook's Turtles, however, swung the balance of power towards the Union.

Grant's campaign started on 5 February 1862 with the bombarding of Fort Henry on the Tennessee River with four of Foote's ironclads and three wooden gunboats. Although the defenders' artillery was well handled, hitting one ironclad and killing 20 men, the fort surrendered and Grant's 15 000 troops, all moved by water transport, occupied the ground. The wooden gunboats carried on upstream and destroyed the only railway bridges over the river causing multiple problems for the Rebels who would have difficulty moving troops and materiel. A couple of weeks later Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River was struck. These combined actions led to the Confederates being forced to give up Nashville on 23 February and generally retreating to form a new line centred on Corinth. However, several moves and counter-moves on both sides, coupled with some disastrous blunders and mistakes, led to the first great slaughter of the war at Shiloh on 6/7 April in which both sides took enormous casualties. The net result of this campaign, and it was of major importance, was that the Confederacy lost the Iron Foundry at Clarkesville, the second largest in the South at that time, as well as the Gun Powder Plant and other industries at Nashville.

The Rebels were now reeling on the back foot and soon their formidable fortress just downstream from Cairo, their 'Gibraltar of the West', had to be abandoned. The Western Gunboat Flotilla moved downriver where, in a combined operation with Pope's Army of Missouri, they defeated and captured the fortress on Island No 10, forcing the Confederates to retire to Memphis as their next line of defence. After consolidating, the Flotilla moved off downstream to its next confrontation.

Meanwhile, influenced by developments in Europe, momentous events had been taking place at two ship-yards a thousand miles away, in the North at New York and in Virginia, in the Norfolk Navy Yard. Recently, between 1853 and 1856, England and France had fought the Crimean War against Russia and, using the experience gained there, each nation had built fully ironclad warships. This innovation, along with efficient screw propulsion, had, overnight, changed the face of naval warfare which had been almost static for two hundred years. Both sides in the American Civil War were developing their own versions of this new technology.

At the start of the war the Confederate Navy had taken possession of the hulk of the steam-frigate USS Merrimack at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia when it was abandoned. Using a similar concept to that which Pook had used in designing his 'Turtles', the Rebels had constructed an armoured casemate on the deck of the frigate and fitted her out as a blockade buster to break the blockade of Richmond on the James River. (This concept was to feature in all the Confederate ironclads which were built thereafter, a few of which were formidable). A key feature of her design was the huge cast-iron 'beak' or ram fitted to her bow which would turn the ship itself into an offensive weapon. Not since the days of the slave-powered rowing galleys had this method of warfare at sea been used. Steam power, especially in combination with efficient screw propellers, now gave navies the means to resurrect the concept. The idea was carried over to the Confederate River Navy who had to contend with the formidable gunboats of the Union.

Frantic efforts soon had the Rebels believing that they had the means to counter Foote's Flotilla. At Plum Bend below Fort Pillow on the Mississippi, this was revealed. As the US Army's cock-sure Western Gunboat Flotilla progressed downstream, bent on further successes, it received a shock! A makeshift fleet of stern-wheeler riverboats converted by the Rebels with both iron and cotton bale armour and iron beaks at the prow fell upon them at Plum Bend! May, 10, 1862 was to prove the day of the first real battle on the inland waters. The elated Southern Fleet captain afterwards crowed to General Beauregard that the Yankees would never penetrate farther down the Mississippi! This was after he had holed two of Foote's 'City' Class boats, putting them out of action for weeks, but more surprises were to come just four weeks later.

On a fine Sunday morning, 6 June 1862, the citizens of Memphis came out in their thousands onto the bluffs overlooking the river on learning of the approach of the Union gunboats. They were there to cheer on their inland navy to another drubbing of the hated Federals, but, sadly, just two hours later, they made their way back as the home team suffered a serious loss. A frail, harmless looking Pittsburgh civil engineer, Charles Ellet, Jr, had taken an idea to Secretary of War, Stanton, and sold him on it. On that sunny June morning as the Rebel rams stood out confidently into the wide Mississippi to give battle to Foote's gunboats, they were in turn fallen upon by a fleet of nine Union rams, also converted riverboats, surging downstream at fifteen knots. It was almost a private affair, Ellet family members heading up many of the crews, and, within a short time, backed up by the guns of the 'City' Class ironclads, only one Rebel boat had managed to get away downstream. The citizens watched in silence as four men under Charles Ellet, Jr, marched through the streets and raised the Stars and Stripes over the post office. The Union force had only one casualty, Ellet himself, who died of his wounds. Incidentally, this was the last time in United States history that a privately raised fighting force was ever used in action.

Only one bastion remained in the path of the Western Gunboat Flotilla and Grant's Army - this was Vicksburg, 300 miles (483 km) downstream, but it was to be another year before it would be defeated. Essentially, although in the autumn of 1862 the Navy would take over the Gunboat Flotilla, the river war was over barring some odd actions at Vicksburg and on the Yazoo and Red rivers, which, in themselves, had little effect on the outcome of the War.

Before the last quarter of 1861, stories were emerging of what the Confederates were planning and putting into effect at Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia and certain elements within the US Navy pressed the Secretary to initiate some sort of answer. This he did, calling for designs from marine architects for an ironclad ship capable of matching what was becoming a worrisome subject for many of the US Navy staff. Influenced to some degree by Lincoln, who was impressed by the revolutionary design submitted by John Ericsson, a Swedish inventor, the Navy placed an order. Ericsson was a stormy petrel with a controversial, chequered career, but his inventions and designs were nevertheless highly respected. To match his promise that he would have a ship ready for combat within four months, he took charge of all the necessary sub-contracting. By sheer drive, he had his ship, the revolutionary designed USS Monitor, ready for fitting out at the quayside of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in just 118 days. It was the end of January 1862 and just two weeks before the Confederates floated the Merrimack, now named the CSS Virginia, out of her dock.

Hampton Roads

On 8 March 1862, with five Union ships in Hampton Roads guarding the mouth of the James River outside Norfolk, the CSS Virginia steamed out, ostensibly on a trial run, but only her captain, Franklin Buchanan, knew what was to happen. She steamed straight for a Union sailing vessel at anchor, the 24-gun Sloop, USS Cumberland, and sent several shells into her side before ramming and tearing a seven foot hole in her hull which sent her to the bottom. While this was happening the other two sailing vessels sent numerous broad-sides at the Virginia but shells and shot which struck either exploded or bounced off, showing no signs of damage. After wrenching free from the sinking vessel, but losing her ram in the process, Virginia attacked the 50-gun USS Congress, raking her with fire and igniting her magazine, which blew up. The screw-frigate, USS Minnesota, in trying to go to her sister ships' rescue, went aground during her manoeuvring and drew the Virginia's attention. However, Virginia's deep draught prevented her from closing within range. Night was falling by this time and Virginia broke off to return to Norfolk. Although the victor of the engagement, she had been struck 98 times, two of her crew had been killed and Buchanan himself had been wounded. Not a single deck fitting survived.

For days frantic messages flew to Washington and New York asking when the Monitor could be ready to sail. There was almost a sense of panic in the upper echelons of the US Navy as, having already lost two ships, it was feared that a disaster was about to happen and that the whole Union fleet at Hampton Roads would be annihilated.

The next morning, after some repairs and replenishing ammunition, the Virginia steamed out to finish the job. Her crew was elated and confident as the ship neared their first target, the Minnesota, but her officers were puzzled by what appeared to be a barge alongside which seemed to be taking one of the Minnesota's boilers on board. Suddenly, as they were coming within range to engage, the 'boiler' ran out a gun and fired. The Battle of Hampton Roads had begun; an event which would alter the face of naval warfare in one fell swoop. Although the fight went on for some hours, neither side was able to destroy or even seriously damage the other despite the Monitor's 175 pound shot from her two 11-inch guns.

A few days later, when the news reached Europe, The Times of London reported: 'Whereas we had available for immediate purposes some 148 first class warships we now have but two; HMS Warrior and her sister, Ironside. There is no ship in the Royal Navy apart from these as it would be madness to send any others against the little Monitor.'

Little she was, at a mere 1 000 tons, but her efficient screw meant she had no need of an auxiliary sail. Described as a cheese box on a raft, her turret was driven by a small donkey engine and her gunners actually developed a method of shooting as the turret turned. The Monitor was a prototype; many further developments of the design were built not only during the Civil War but by other navies right up to the early twentieth century.

By mid-July 1862 the blockade was very much in place. Flag Officer, later Admiral, David Farragut had taken New Orleans after subduing the forts guarding the mouth of the Mississippi and his fleet had steamed upstream to meet up with Foote's Gunboats at Vicksburg although even the combined fleets could not break the defences. Many more actions, mostly minor, were still to take place. In August 1864, Farragut was to issue his famous order: 'Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!' as his Gulf Fleet entered Mobile Bay, the last great sea/land confrontation.

Conclusion

How effective was the blockade? It is still argued by historians whether or not its declaration was necessary, but declared or not, it was vitally important that the Union had to inhibit the South's trade and prevent it from easily obtaining war materiel. Figures differ, but there is some agreement amongst sources that, on average, the Federals caught one out of every six attempts to run the blockade. At the start of the War, the Union had some assistance from the Rebels, however. Although it was never Confederate policy, some one million bales of cotton were deliberately held back by exporters during the first year of the war in an effort to force British and French acknowledgment of the Confederacy as a nation. Most of this crop rotted on the quaysides, thus rendering the crop of 1861 effectively lost as a cash generator.

Blockade running became a very lucrative industry with huge profits for those who evaded the blockade. Cotton could be bought for a mere 3 cents a pound at the quayside and auctioned two weeks later in Liverpool for between 34 cents and a dollar per pound. A steamer delivering a cargo of 1 000 bales could make a profit of $250 000. Most skippers were British and some 66 vessels left Britain for the trade, about forty of which were eventually captured or destroyed. The Confederate Government as well as a couple of the Southern States even had their own blockade runners. The great majority of the runners made massive profits. Some 540 000 bales of cotton were sent out through the blockade to England, although it is estimated that as many were smuggled into the North by other means. Many Yankee businessmen were not truthfully patriotic; some even sending pork lard barrels down south, packed with pistols! It is also astounding how much war materiel got through. In February 1863 alone, 110 000 rifles made it through and Robert E Lee's men carried imported canned beef and pork with them on their way to Gettysburg. Fashion conscious Southern women were even able to secure a supply of crinoline hoops and corset stays throughout the War; these products were the last to be jettisoned overboard to lighten ship in the event of a sea chase. Stories of the blockade could fill many books.

The little blockade-runner, CSS Sumter, mentioned earlier in this article, had to be abandoned in Gibraltar by Semmes and his crew, who then made their way overland to England, where they would eventually set sail in what was to become the CSS Alabama. The Sumter was sold at auction to a new owner, an Englishman, who renamed her Gibraltar. She is credited with several lucrative blockade runs, quite a remarkable history for one little vessel, which, a mere three years previously, had been a mail packet sailing between Cuba and New Orleans.

Although the Confederate States' Navy's dream was to have a fleet of commerce raiders active on the high seas, this was not to be. Commander James Bulloch had performed miracles in the way his subterfuges succeeded in acquiring vessels and having others built. The Alabama, Florida and Shenandoah were all built in Britain and spirited away to become armed commerce raiders, a technique adapted years later by the Germans in both World Wars. The successes achieved by these vessels, not only in terms of tonnage sunk, which was considerable, caused huge consternation in the Union. Some 236 vessels, totalling about 110 000 tons of shipping, were lost and marine insurance rates soared. Over 800 000 tons were written off and re-registered under other flags. What had been the largest mercantile fleet after that of Great Britain in 1861 was one of the smallest in 1865. Conversely, the United States Navy, with its mere 90 ships of all sizes ranging from harbour tugs to the five fast frigates of 1861, ended the war as the largest navy in the world.

The Confederate States' Navy, literally with no ships at the start, had, by the war's end, some 250 vessels on register, which, of course, included those sunk and captured. In real terms, considering that the lack of facilities was a major factor, it means that the Confederate States' Navy showed as much ingenuity and drive as that of the Union, if not more so, especially in its reliance on ironclads, its successful revolutionary, albeit suicidal, attack by a submerged vessel, and its extensive and highly effective use of underwater mines (referred to as torpedoes), which sank some 45 Union ships.

There is no doubt that both in the popular concept and amongst historians, there is a measure of glamour attached to the Confederacy. Even taking into consideration the impact that such ships as the USS Monitor and 'City' Class ironclad gunboats made on history, it is Confederate ships that are typically mentioned when the subject of the Civil War on water is raised. The undoubted romance of vessels such as the Alabama, Florida, Shenandoah and the submersible, Hunley, always seem to spring into mind, possibly influenced by a sense of championing the underdog. The fact that the cause of the war was essentially an armed insurrection which had to be put down is conveniently forgotten, except when the emotional matter of slavery is introduced.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Bern, By Sea and River: The Naval History of the Civil War (An Alfred A Knobf re-print, 1962).

Catton, Bruce, The Penguin Book of the American Civil War (first published in the USA by American Heritage Publishing Inc, 1960, Penguin, 1966

edition).

McPherson, James M, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press Inc, 1988).

Pratt, Fletcher, A History of the Civil War (originally published as Ordeal by Fire, Pocket Books Inc, Revised, 1948).

Semmes, Raphael, Memoirs of Service Afloat during the War Between the States (edited by Philip van Doren Stern, Fawcett Publications Inc, 1962).

Symonds, Craig L, Confederate Admiral: The Life and Wars of Franklin Buchanan (History Press, 2012).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org