The South African

The South African

With the centenary of the Great War of 1914-18 approaching, there will be ceremonies to honour the dead from that war around the world. It was a terrible war with huge losses and when Britain declared war on Germany, all the British Commonwealth countries were automatically at war too. It was only four years after the Union of South Africa had been established and there were many Afrikaners who refused to fight on the side of the enemy who had invaded the Boer Republics merely to grab the gold that had been discovered on the Witwatersrand. In 1914, some of these Afrikaners went into armed rebellion in opposition to the decision to invade the German territory of South West Africa on behalf of the British. However, in spite of this opposition, there were many English and Afrikaans-speaking South Africans who did enlist to fight for Britain. I would like to share with you a true story of a brave soldier called Jackie.

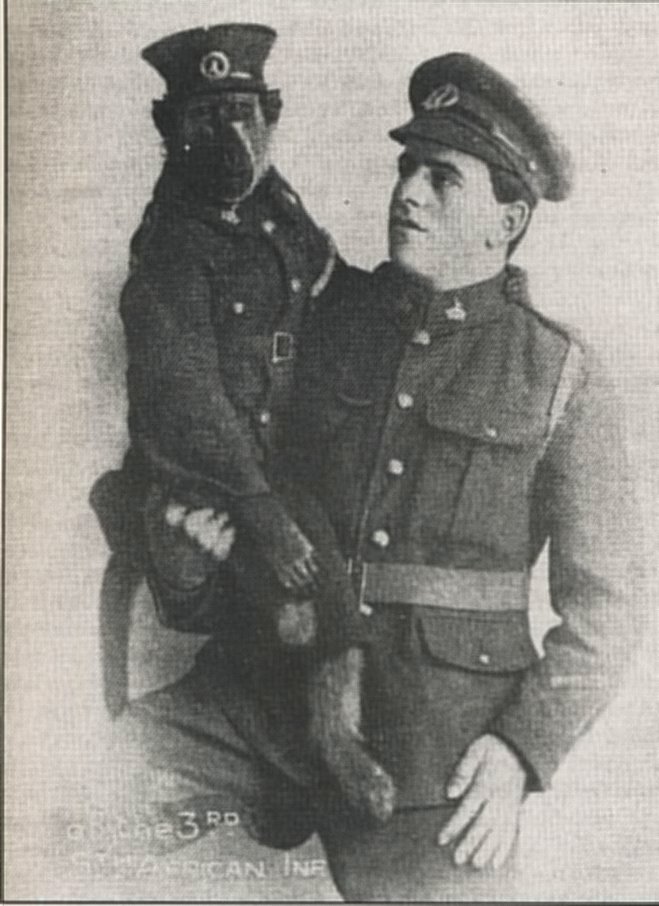

In 1914 a young man called Andrew Marr lived on Cheshire Farm in Valeria, Pretoria. He had raised an orphaned baboon that regarded Andrew as his alpha male and would not be parted from him. Andrew went to enlist as a soldier, but said he could not leave Pretoria without his baboon. The animal was well behaved and described as 'dignified'. In any event, the recruiting officer was sympathetic and agreed that the baboon could be the battalion's mascot and so Andrew and Jackie went off to train to be soldiers. Jackie drilled and marched like any other soldier and when the 1st South African Brigade was diverted to Egypt, they all went 'up North' to help the British against the Turks, who were threatening the Suez Canal and therefore British interests in the Suez Canal Company. At the battle of Agagia, a hand grenade fell beside Andrew and, without any hesitation, Jackie picked it up and threw it back! When Andrew was shot in the right shoulder, Jackie tried to ease the pain and licked the wound until the stretcher bearers came. By cleaning the wound, Jackie prevented the wound from going septic and Andrew healed quickly.

When the South African brigade was sent to Flanders, Belgium, Jackie was enlisted as a soldier, given a uniform and rations and treated like any other soldier. He was accepted as a comrade in arms, would salute the army officers on their rounds and light a cigarette for a 'pal'. Jackie shared the mud and privations of the trenches and went 'over the top' with the Regiment. He also went on guard duty at night with Andrew and saved the men time and again because his sight and hearing were acute. When he heard the movement of the enemy, Jackie would give a few short barks and tug Andrew's sleeve. Together they survived the noise and terror of Delville Wood in 1916.

It was at the battle of La Clyte in 1918 that Jackie was wounded. He was seen trying to build a little wall of stones around himself like the other soldiers when he was hit by a piece of shell. At first he tried to carry on defending himself while in terrible pain. His right arm was bleeding and his left leg was all but shot away, attached only by a thin strip of sinew. He refused to allow the stretcher bearers to come near him, but let Andrew carry him to the medical station. Colonel R N Woodsend of the Royal Army Medical Corps wrote of the pathetic sight of Jackie moaning with pain, carried by his keeper who was crying his eyes out in sympathy. Andrew begged the surgeon to help the comrade who had saved his life in Egypt. Jackie 'lapped up the chloroform as if it had been whiskey' and the surgeon cut off the leg with a pair of scissors. They were not sure if the chloroform and the operation would kill Jackie, but when the OC went to check up on him at the Casualty Clearing Station, Jackie sat up in bed and saluted him.

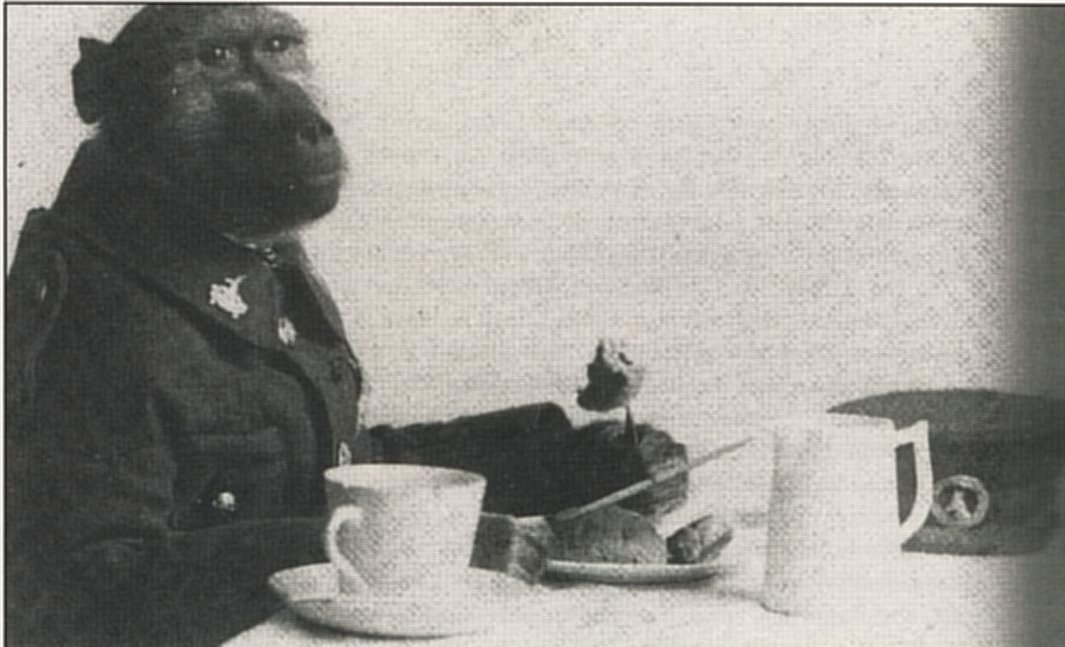

Andrew and Jackie were sent to London to recover and Jackie's proudest moment was to participate in the Lord Mayor's Day Procession in London. They managed to collect a huge amount of money for the Widows and Orphans Fund by allowing the public to pay half a crown to shake Jackie by the hand and five shillings to kiss the baboon. When the war was over, they returned home to South Africa where Jackie dined at Johannesburg's Park Station restaurant. He was wearing his uniform proudly with one gold wound stripe and three blue service chevrons for his three years' front line service.

Jackie received his discharge papers and a pension and a Pretoria Citizen's service medal. He and Andrew went back to Cheshire Farm in Valeria and tried to settle down quietly with their 'shell-shock'. In 1922, there was an electric storm in Pretoria that was louder than usual. The thunder claps were too much for Jackie and he suffered a heart attack and died. He was a great South African*.

* Although all kinds of people from southern Africa enlisted for service in the Great War of 1914-1918, when they came home after the war, they identified themselves as 'South Africans' .

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org