The South African

The South African

Introduction

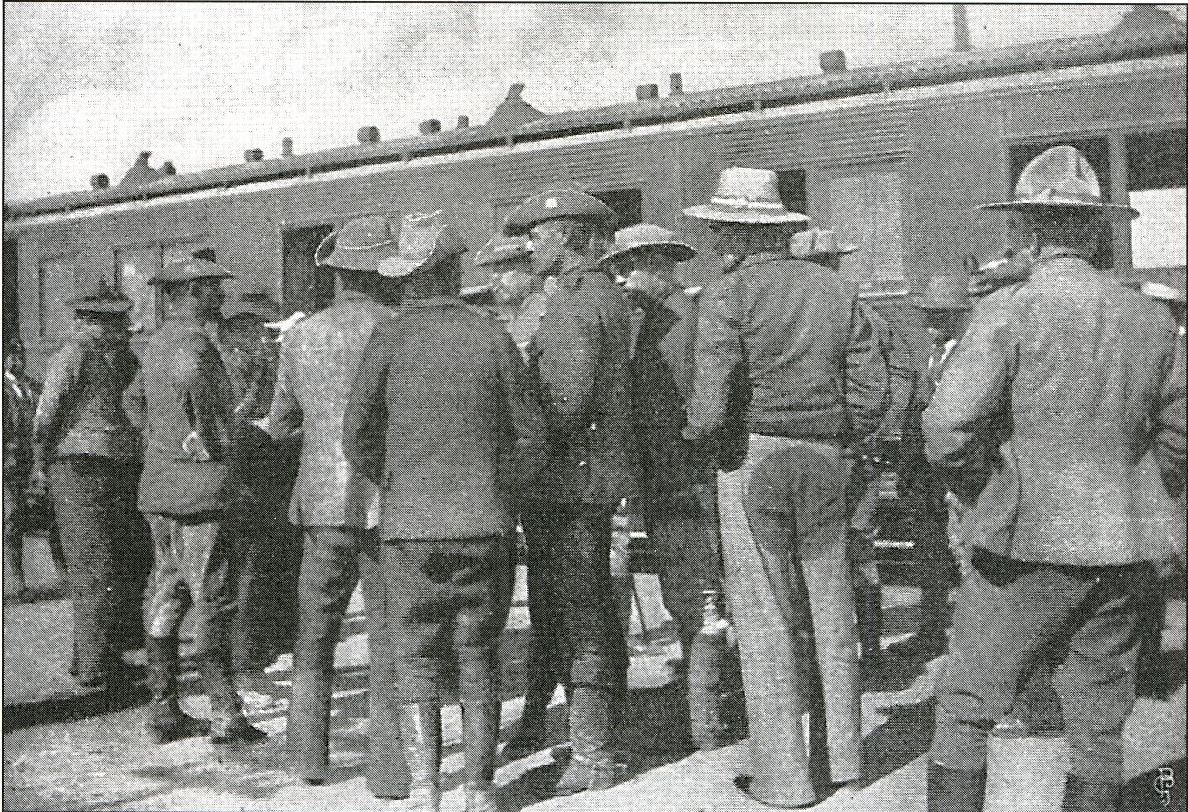

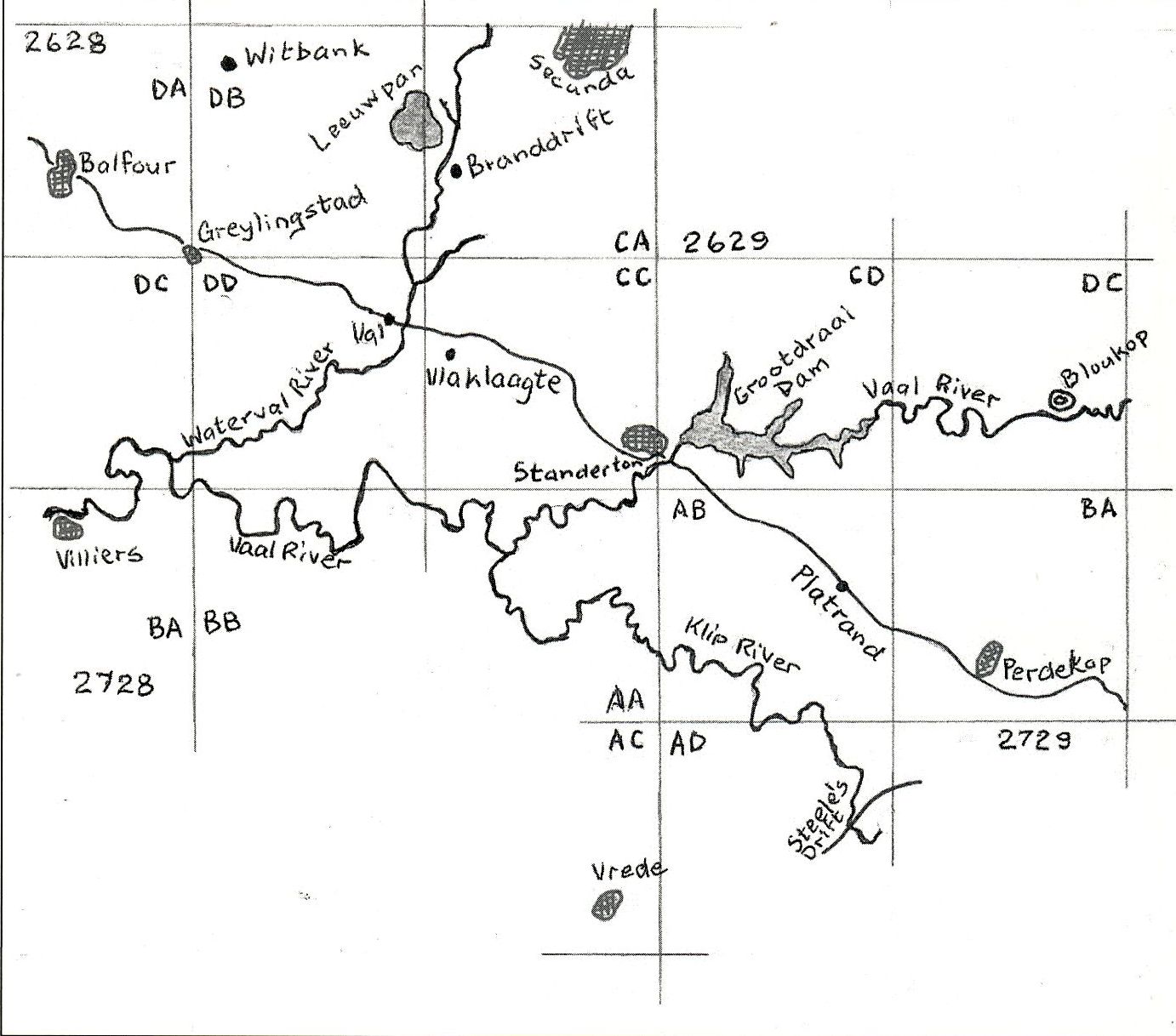

There is a famous picture of the Boer leaders about to take a train from Val Station (on the main line between Johannesburg and Durban, about 20 km east of Greylingstad) to Klerksdorp. Boer leaders from the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (the Transvaal) and the Orange Free State were to meet in Klerksdorp to decide on whether to continue with the war or to negotiate peace terms with the British Government. The date was 6 April 1902. Commandant-General Louis Botha had arrived at the station in a Cape cart the previous day, accompanied by an escort of commandos. Botha and a number of Boer officers, now under safe conduct from the British, met in a room of the Val Hotel which still stands on the north side of the station. Hardliners among his officers were against any kind of negotiation with the British and the Boer governments' intentions needed to be clarified.

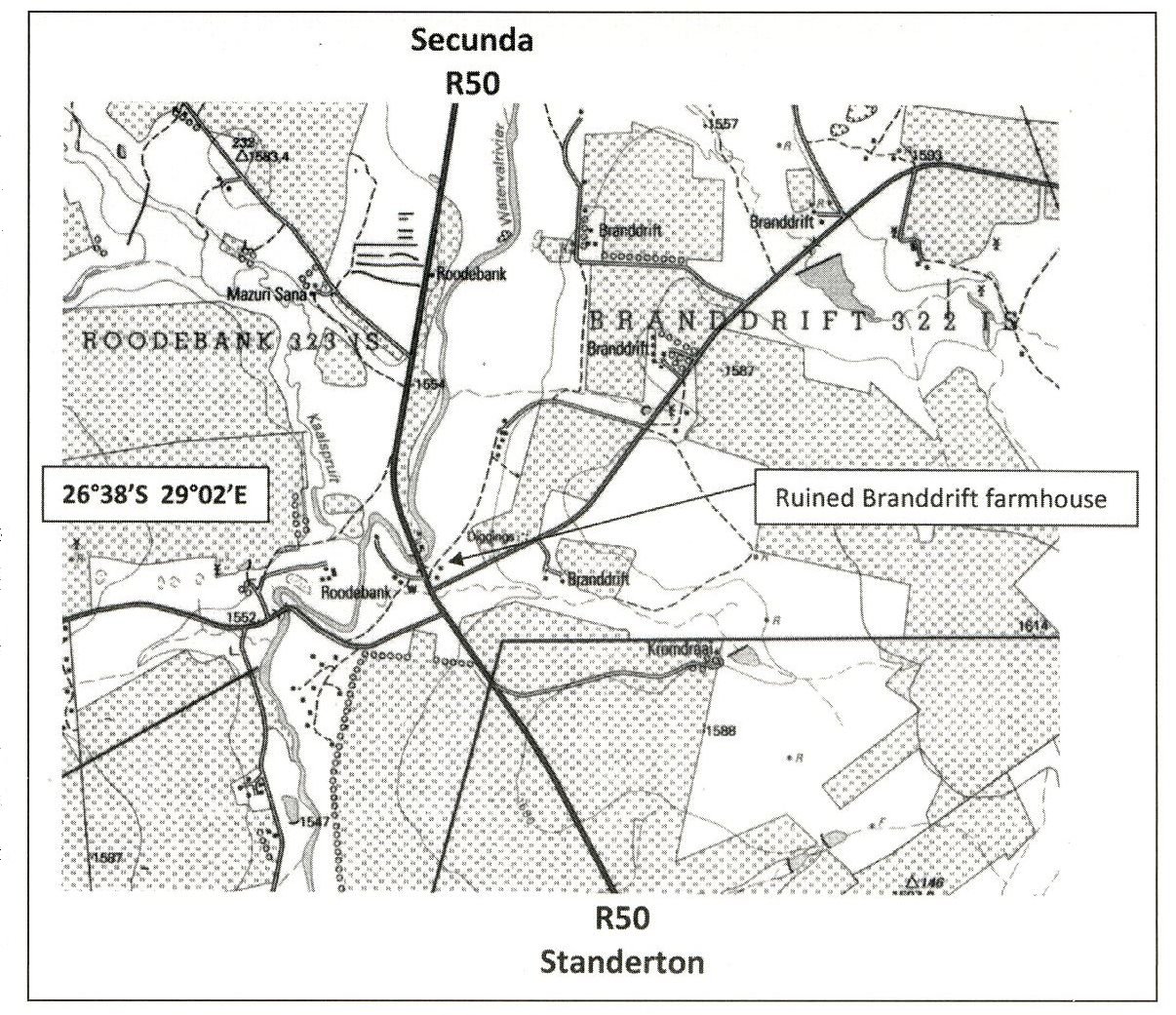

Ten months previously, another meeting had taken place not very far from Val. On 20 June 1901, a very important day of discussion. had brought about some vital decisions on Boer plans for the future. The Boer leaders met in the Branddrift farmhouse (Maurice, 1905, p 205; although Childers (1907, P 296) says they met at 'the farm Waterval, near Standerton', by which he must have been referring to a farm near the Waterval River since there was no actual farm by that name north of Standerton) alongslde the drift of the same name over the Waterval River. At the meeting were Acting Transvaal President Schalk Burger and Orange Free State President Marthinus Steyn, Transvaal State Secretary Francis Reitz, Commandant-General Louis Botha and Chief Commandant Christiaan de Wet, Generals Hertzog, Viljoen, Spruyt, De la Rey, Smuts, Muller, Lucas Meyer and a number of other commandants and officers (Maurice, 1905, p 206).

At first the meeting was convened in a secluded place somewhere along the Waterval River but it was then moved to the nearby Branddrift farmhouse. This was the most secure place they could find in an area criss-crossed by British columns. They kept well away from both railway lines - the main Johannesburg-Natal line and the ZASM line from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay (now Maputo). Blockhouses, only one thousand yards (914 m) apart and connected by barbed wire, protected the lines. Armoured trains operated on each of these lines and British reinforcements could be rushed to any point where they might be needed.

Boer scouts kept the area around Branddrift under constant surveillance, for security was absolutely vital. (Local oral tradition has it that the Boers even had a sentry on the roof of the farmhouse.) Should the British have managed to locate this concentration of the entire senior leadership of the two republics, the capture of even a few of them would have been disastrous for the Boer war effort.

General Botha meets Lord Kitchener

The Boer krygsraad at Waterval had been preceded and indeed precipitated by an earlier meeting between Botha and the British commanding general, Lord Kitchener, in Middelburg on 28 February 1901. Mrs Botha, living in Pretoria, had been given a letter to deliver to her husband (Meintjies, 1970, pp 78-81), wherein it was proposed that Botha and Kitchener should meet to see if common ground could be found to arrange terms of peace. Anything and everything was open to discussion 'except that the question of independence of the two republics was not to be discussed in any way' (Childers, 1907, pp 183-93). It was High Commissioner for South Africa, Sir Alfred Milner's proviso that no discussion was to be made on the subject of independence. (Chapter VII of Leo Amery (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, gives full details of the terms that were discussed at this conference).

The question of independence, however, was certainly going to be Botha's first point of departure during the meeting, but nevetheless details of a process leading to a cessation of hostilities were discussed in a reasonable and even friendly spirit. Botha clearly realised that, at some time or another, the war could only be ended by negotiation. (Meintjies [1970, p 81] writes that posters in London announced that Botha had surrendered while a photograph of Kitchener, Botha and their aides was circulated after the Middelburg meeting and certain Boer commandants were convinced that Kitchener was now a Boer prisoner-of-war).

The decision to continue the war

According to Childers (1907, pp 183, 191), a letter was sent to the British High Commissioner, Lord Milner, and then to the British Government, who returned it for Kitchener to send a final version to Botha, who declined to negotiate further. Botha then travelled to Vrede in the Orange Free State to meet with General de Wet on 25 March. It is not clear whether President Steyn was also present at this meeting, but a number of matters were discussed and they 'parted with the firm determination that, whatever happened, we would continue the war' (De Wet, 1902, p 242).

A letter was sent to the Government Secretary of the Orange Free State after a meeting of the Transvaal government and their generals on 10 May 1901. This letter suggested an approach to Kitchener for permission to send ambassadors to Europe to place before President Kruger 'the condition of our country'. Furthermore, it was proposed that an armistice be requested so as to decide 'what we must do'. (This letter, translated into English, is quoted in De Wet, 1902, pp 245-7.) President Steyn was very disappointed with the sentiments expressed in this letter and insisted that a joint meeting of the two Republican governments be organised somewhere on the Transvaal Highveld at an agreed venue as soon as possible. (Childers, 1907, p 278, describes Steyn's reaction to the letter).

Following representations from Botha and Acting Transvaal President Schalk Burger, Kitchener permitted the Boers to send a telegram to President Kruger in Holland. This was done via the Netherlands Consul and using their cipher. Kruger's reply was to the effect that the Boers should fight on even though there was little chance of any intervention by a European power. He said that there were some signs of public opinion in Britain becoming opposed to the war. As he was now remote from the war, he felt that any decisions should be taken by a joint decision of the two Republican governments. Kruger's telegram was an important document tabled at the meeting in the Branddrift farmhouse (Pakenham, 1979, p 513; Hancock and van der Poel, 1966, pp 399-400).

The Krygsraad at Waterval

The Free Staters set out for the Transvaal on 5 June together with General Koos de la Rey who had joined them from the Western Transvaal. Before travelling further, they had first to attempt the rescue of a Boer women's laager which had been captured by a British column at Graspan, east of Reitz (De Wet, 1902, pp 249-51. A more detailed account of Graspan can be found in J and J A J Lourens, Te na aan ons hart, 2002, and there exist also a number of accounts of this clash by Australian soldiers who were involved).

The Free Staters, with De la Rey and his staff, headed north from Vrede and crossed the Vaal River near Steele's Drift before striking the main railway line from Natal near Platrand on the night of 14 June. Their escort brought a blockhouse under fire by way of diverting the attention of its small garrison while the rest of the party rushed across the line. De Wet describes how the 'first of our men had hardly got seventy paces from the railway line when a fearful explosion of dynamite took place'. There were apparently casualties; two dead horses and a rifle were found near the line the following morning. The Free Staters then made their way to Blaauwkop on the Vaal River. This was Commandant Coen Britz's base, where they awaited news of the arrival of the Transvaal party and the site of the meeting (De Wet, 1902, p 253. De Wet said there were no casualties, but Maurice, 1905, tells of the two dead horses).

Somewhere along the Waterval River, in an area practically denuded of human and animal population as a result of the' British 'scorched earth' policy, seemed a likely place to meet. The Transvaalers made their way from the hills around Amsterdam and, with some difficulty, evaded pursuing British columns. General Ben Viljoen provided the escort and the scouts who brought them safely to the farmhouse at Branddrift (Viljoen, 1903, p 229). Nevertheless, they had been so closely pressed at one stage they had been forced to abandon all their vehicles (Maurice, 1905, p 205).

Alerted by despatch riders, the various parties came together for their meeting. The principal reason for the meeting was to decide whether or not to continue the war, but a number of other matters needed to be discussed too, and important decisions needed to be made. Steyn was in no doubt about his determination to fight on to the bitter end, but recent Boer successes made this matter almost a foregone conclusion for the Boer leadership. Boer successes at Vlakfontein in the western Transvaal (now North West Province) on 29 May (Childers, 1907, pp 281-5, gives a map and a detailed account of this action) and Wilmansrust on 12 June (Childers, 1907, pp 294-6) had given them encouragel11ent enough. The recent harassment and battering of a British column in a running fight from Rietfontein, near Bethal, all the way to Mooifontein, just north of Standerton, had also been noted (Childers, 1907, p 297; Viljoen, 1903, pp 225-6).

Thus it was resolved 'that no peace shall be made, and no peace proposals entertained that do not ensure our independence, and our existence as a nation'. More importantly, Botha and Smuts pointed out that although Boer tactics were working well, they did not have a strategy that would bring the war to a conclusion in their favour (See Appendix below for definitions of tactics, strategy and grand strategy by B H Liddell Hart). It was unlikely that the Boers could ultimately prevail against the resources and manpower that the British had at their disposal. However, what was needed was a number of big successes that would convince the British of the futility of continuing to fight. The Cape Colony had suffered no devastation and many of its inhabitants were Boers, or at least sympathetic to the Boer cause.

The Free Staters had attempted an invasion of the Cape Colony earlier in the year but Christiaan de Wet's foray over the Orange River had not been successful. The Transvaal Boers were urged to make another attempt. De la Rey made an offer of a commando of experienced men and Smuts was given command of the venture. At the same time, Botha undertook to make a similar foray into the Colony of Natal. (Deneys Reitz's Commando is a prime source on Smuts's invasion of the Cape, but see also Shearing [2000] for detail of this remarkable exploit. Botha was less successful in what became merely a raid along the border of Natal - see Childers, 1907, pp 334-59). Both caused the British some disquiet and the realisation that some drastic counter-measures were needed.

After the meeting From Branddrift, the various parties made their way back to their bases. Perhaps to put the British off the scent, or because a direct route to the east was barred by British columns, the Boer leaders headed to the west and only split up at the farm Witbank, about 26 miles (42 km) east of Heidelberg. From there the Free Staters and De la Rey and his men made for the Waterval River and crossed the railway line near Vlaklaagte guided by Commandant Henk Alberts of Heidelberg. De Wet had farmed at Zilverbank before the war for two years and so knew the area fairly well (De Wet, 1902, p 254). He describes Alberts as a 'valiant soldier' and a 'most sociable man'.

Near the Vaal River, the Free Staters and De la Rey parted company, the latter crossing the Cape railway line near Meyerton and De Wet and his President entering the Free State at the drift over the Vaal at Villiersdorp (now the town of Villiers).

Viljoen's orders were for him to take his commandos to the north of the Delagoa Bay railway line, which did not please him at all. Having been pursued by British columns, he had crossed the Delagoa Bay railway line with some difficulty and now he was being ordered to repeat the operation and cross back to the north (Viljoen, 1903, p 229). A few months later, on 25 January 1902, Viljoen was captured and sent as a prisoner-of-war to St Helena.

The Transvaal Government travelled safely back to the hills and kloofs of the eastern Transvaal.

After this there were no more joint meetings of the two Republican governments until the April 1902 consultations in Klerksdorp when it was agreed to approach the British with a joint proposal for negotiations about peace. By then, many felt that the bitter end had indeed been reached, though many others did not. It took nearly six weeks of hard bargaining from the time that the Transvaal generals had their meeting in the room in the hotel at Val until, near midnight on 31 May 1902, the Peace of Vereeniging was eventually signed, ending a tragic period of South Africa's history.

Appendix: Liddell Hart's definitions of tactics, strategy and grand strategy

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B H Liddell Hart, was an English

soldier, military historian and leading military theorist. His definitions of tactics, strategy and grand strategy are as

follows:

Tactics: the techniques for using weapons or militarY units in combination for engaging and defeating an enemy in battle.

Strategy: the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfil the ends of policy.

Grand strategy: to co-ordinate and direct all the resources of a nation, or band of nations, towards the attainment of the

political object of the war - the goal defined by fundamental policy.

(For a full discussion, see Liddell Hart's Strategy, pp 319-33).

Bibliography

Amery, L S (Ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa , Volume II (Sampson, Low, Marston and Company Ltd, London, 1902).

Childers, E (Ed), Amery, L S (General Ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volume V (Sampson, Low, Marsten and Company Ltd, London, 1907).

De Wet, General Christiaan, Three Years War (Galago Publishing [Pty] Ltd, Alberton [Reprint of original Archibald Constable and Company, London 1902]).

Hancock, W K, and van der Poel, J, Selections from the Jan Smuts Papers I, June 1886-May 1902 (Cambridge, 1966).

Liddell Hart, B H, Strategy (Faber & Faber London 1954, 1967 [reprint Meridian, 1991]).

Lourens, J, and Lourens, J A J, Te na aan ons hart: Aspekte van die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die Reitz-omgewing (self-published, Reitz, 2002).

Maurice, Major-General Sir Frederick (Ed), History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Volume IV (London, 1905).

Meintjies, Johannes, General Louis Botha (Cassell, London 1970).

Moore, Dermot Michael, General Louis Botha's Second Expedition to Natal (Historical Publication Society, 1979).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War (Weidenfeld and Nicholson Ltd, London, 1979).

Reitz, Deneys, Commando: A Boer Journal of the Boer War (Faber and Faber, London, 1929).

Shearing, Taffy and David, General Jan Smuts and his long ride (Privately printed by the authors, Sedgefield, 2000).

Van der Westhuizen, Gert and Erika, Guide to the Anglo-Boer War in the Eastern Transvaal (printed by Transo Pers, Roodepoort, bound by IPS Finishers, Johannesburg).

Viljoen, General Ben, My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War (Struik [Pty] Ltd, Cape Town 1973 [Reprint of the original Hood, Douglas & Howard, London, 1903]).

Wilson, H W, After Pretoria, Volume II (Harmsworth, London, 1902).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org