The South African

The South African

About the author

Peter Elliott grew up in South Africa and went to school at Bishops in the 1960s. He graduated in law from Cambridge University, and became a corporate lawyer in the City of London. He is now retired and living with his wife in Languedoc, in south-west France. He has returned to his first love, history, and researches and writes on topics with which he feels particular affinity.

Introduction

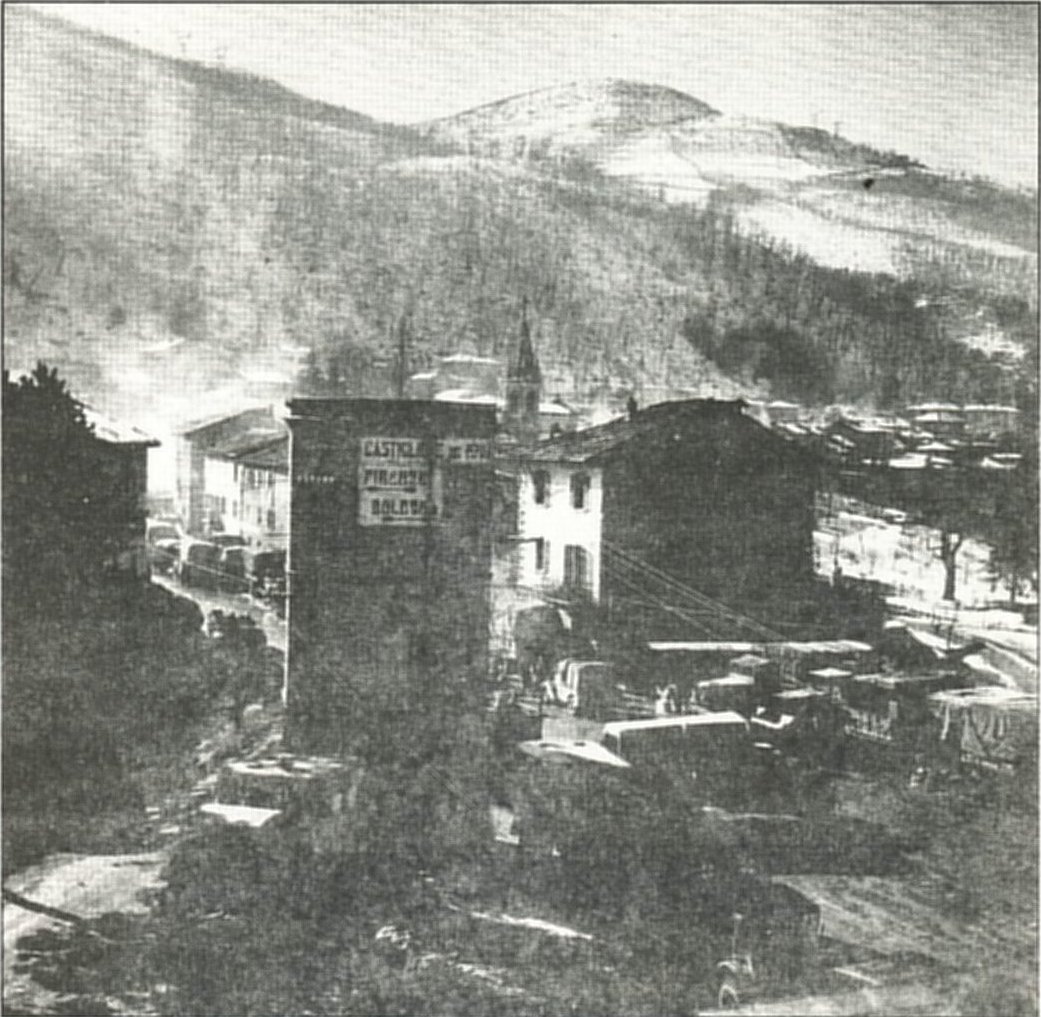

When I was growing up in South Africa, my father often told the story of his good friend, Angus Duncan, the commander of the First City/Cape Town Highlanders regiment, who had been killed at the Battle of Monte Sole, Italy, within a fortnight of the end of the Second World War in Europe. Almost 70 years later, in September 2013, I made the pilgrimage to Castiglione dei Pepoli, in the Italian Apennines, to discover the story for myself. There I met up with Colin Eglin, then 88. We stayed with Colin's friends, Umberto and Gerty Rondelli, in Vergato. Umberto had been about five years old at the time of the Battle of Monte Sole, living in Stanco, and at this young age was unable to distinguish the soldiers by their uniform, but he remembers well the soldiers who gave him chocolates and condensed milk!

Colin was a nineteen year old 'rookie' soldier when he joined the South African troops in the Apennines in 1944. He was well known in this area of the Apennines and had returned there over ten times. He was an honorary citizen of the town of Grizzana Morandi (the latter part of the town's name having been added to commemorate their 'artist son', Giorgio Morandi, who lived and painted in the town). Our visit attracted the attention of the local Bologna newspaper, that wrote of 'L'ex soldato Colin e quella Guerra maledetta' ('The ex-soldier Colin and that damned war'). Sadly, Colin died in Cape Town on 29 November 2013.

Background and earlier phases of the war

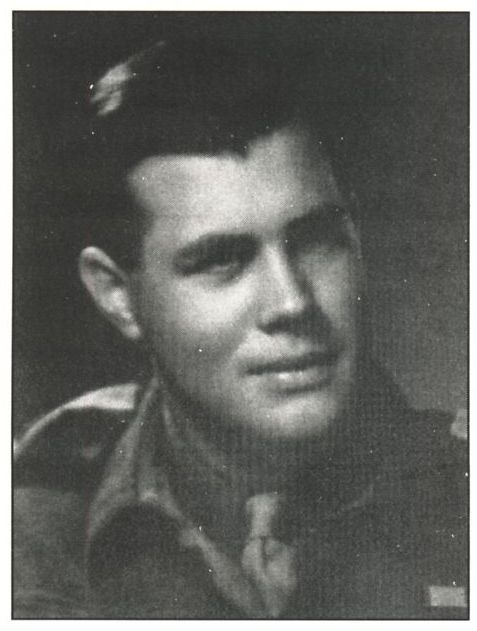

Angus Duncan had been schooled at Bishops and then studied Law at the University of Cape Town (UCT). After a year at the Cape Bar, he had joined the family firm, J C Juta & Co Ltd, the booksellers, who specialised in legal publications. In 1932, he married his wife, Francis, whom he had met at UCT, and he became managing director of the firm some time before the war. In his spare time, Angus was a soldier and when the Second World War broke out, he was Captain and Adjutant of the Cape Town Highlanders (CTH).

Prime Minister J B M Hertzog had not wanted to join the British in the War and had proposed that South Africa should remain neutral, but General J C Smuts wanted to support the war effort. Angus Duncan's widow told of how her husband had met secretly with Smuts when war was declared, to arrange for the regiment's armaments to be secured and hidden in the event that the anti-war lobby prevailed in the crucial parliamentary vote on whether or not to enter the War (email correspondence with Angus Duncan's son, Alastair). In the event, this proved unnecessary as Smuts won a narrow parliamentary majority, was appointed Prime Minister and South Africa declared war. Nevertheless, a substantial part of the population remained ideologically opposed to the war, and conscription was never an option. Accordingly, expansion of the army to fight overseas depended entirely on volunteers, apart from a very limited number of permanent force soldiers. According to Jack Cros (1992, pp xii-xiii), 345 324 South Africans chose to enlist out of a population of some 10 million.

Angus Duncan served throughout the War with his regiment, the Cape Town Highlanders (CTH), except for an interval in the Desert War (North African Campaign), when he had served on the staff of the 2nd South African Division. When the South Africans returned home after the battle of El Alamein, he too returned for leave and reorganisation. The CTH and First City (FC) from Grahamstown formed a combined regiment for service in the 6th South African Armoured Division, then being established. Angus then returned 'up North', sharing the command of FC/CTH. The welding of these two proud units had been the 'hardest job he had yet had in his young life'. (Angus Duncan's early background is drawn from a number of sources, including his obituary in the Bishops school magazine, June 1945, email correspondence with his son, Alastair, and three letters he wrote while at the front, which were published in school magazine between 1941 and 1944).

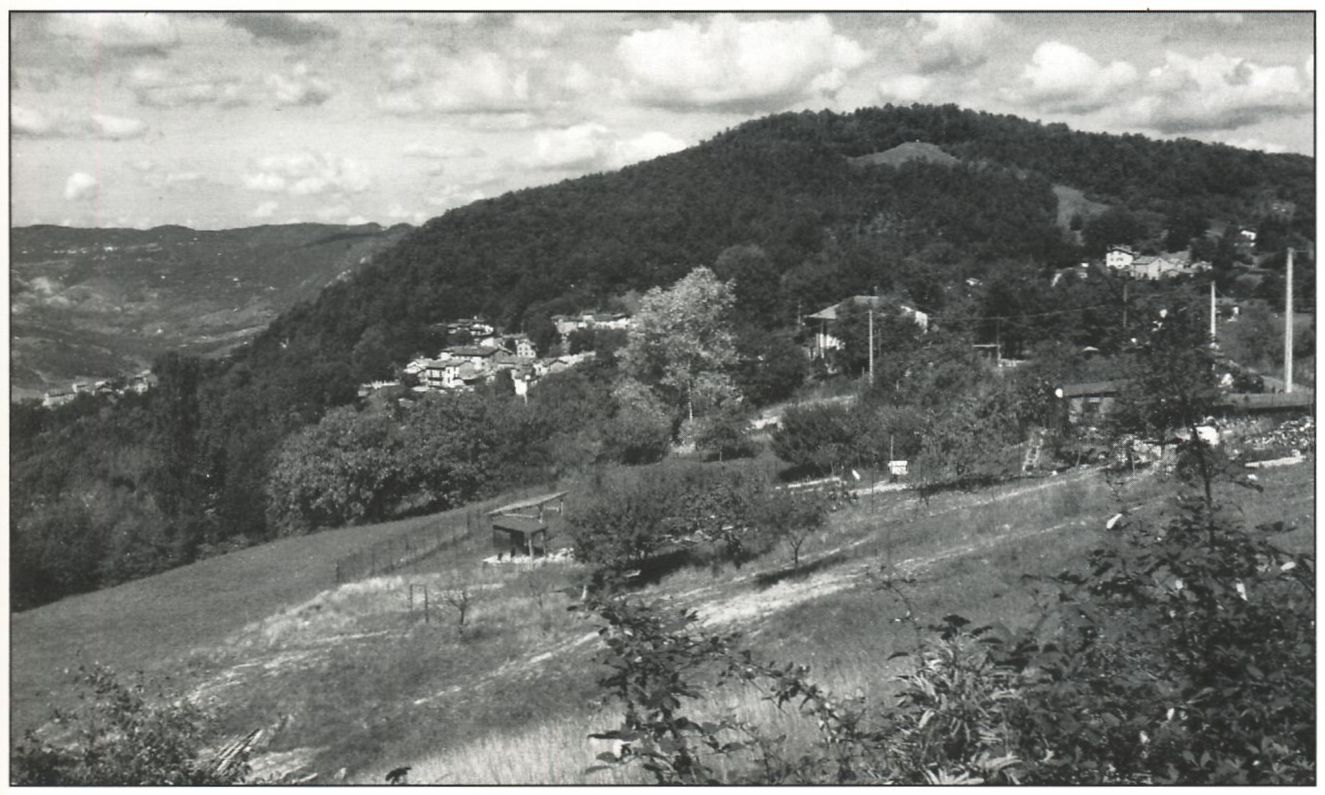

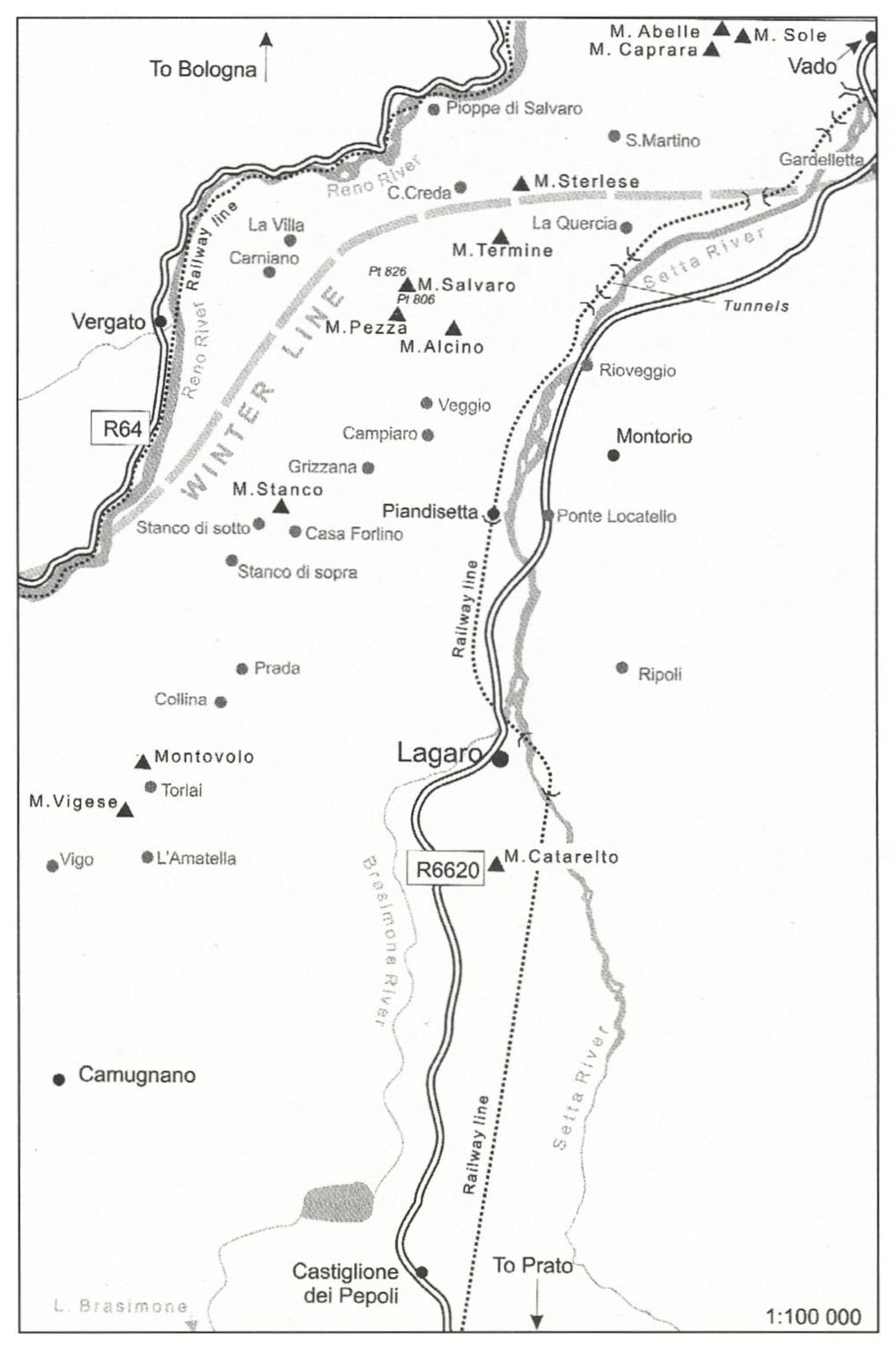

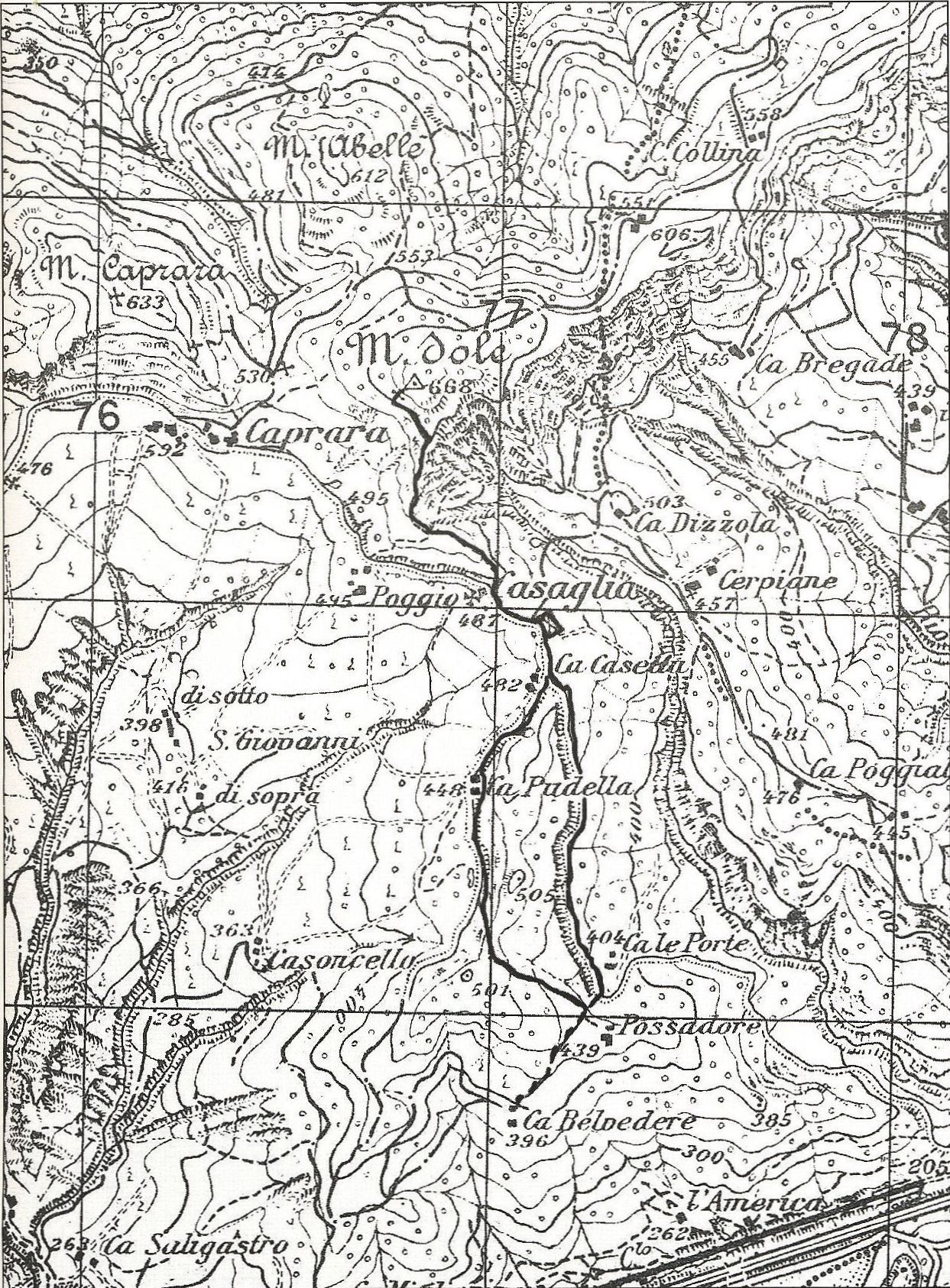

In Italy, Angus was given command of the Reserve Regiment for a short while, but then returned to FC/CTH as its commanding officer, from September 1944 to mid-April 1945. The 6th South African Armoured Division had already been engaged in action at Chiusi in June 1944. They had then worked their way up Italy, liberating Florence in early August 1944 and, at that time, had become part of US General Clark's Fifth Army. By late September 1944, the Division had moved from Prato into the Apennines. Headquarters were established in the village of Camugnano, to the north-west of Castiglione dei Pepoli (called 'Castig' by the South Africans), which was the Brigade HQ. The area around Monte Vigese to the north had then been secured.

Attacks on an enemy occupying natural positions

Monte Stanco is a steep wooded peak dominating the two main roads on either side which lead southwards to Pistoia and Prato, and ultimately to Florence. It had twice been captured and German SS troops had twice re-captured it. It was imperative to the advance of the 6th South African Armoured Division that it be captured, together with the other strategic points, Vigese and Salvaro. Just beyond Salvaro lay Monte Sole, which was the ultimate strategic objective. German troops were dug in on the northern slopes of Monte Stanco. The high ground between Monte Stanco and Grizzana dominated the roads, and the Germans were holding fast there .

The Witwatersrand Rifles/Regiment De la Rey (WR/ DLR) was given orders to take Monte Stanco while FC/ CTH was to take a point one kilometre to the east of this .

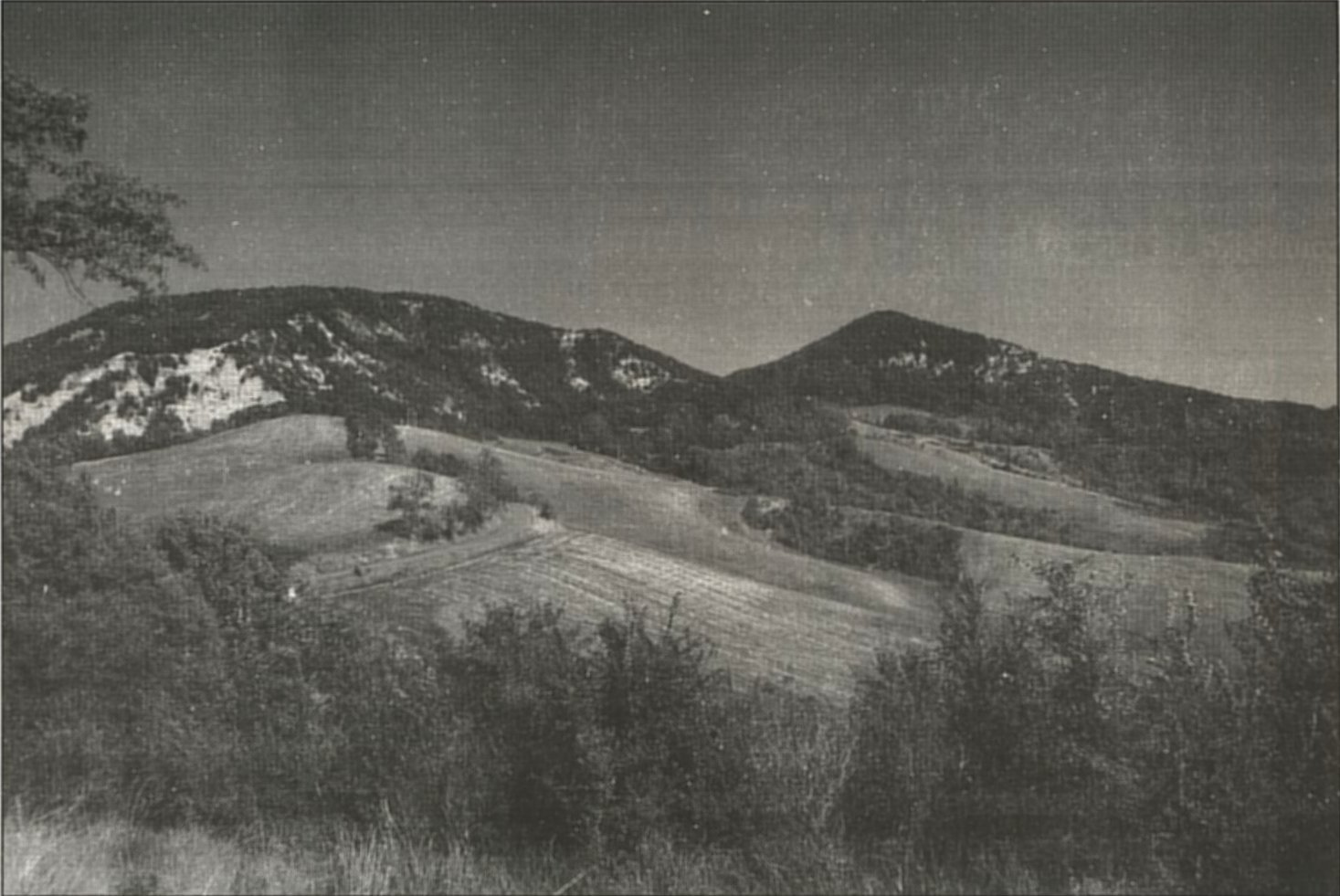

Between Camugnano and Monte Stanco there was a ten-mile, fourteen-hour walk along a slippery Jeep track, which ran east round Monte Vigese to Collina. (The line of the Jeep track can be seen on the path above Collina, a small off-shoot of the village of Monteacuto Ragazza. Behind is Monte Vigese, and in front the ridge, which is clearly visible on a detailed walking map, between Collina and the south-eastern slopes of Monte Stanco. The Jeep track can still be followed some of the way). This track had to be reconnoitred in zero visibility, in the mist, rain, mud and cold. Most of the way there was only sufficient room for one-way traffic .

Angus Duncan's battalion went without proper sleep for three days, and he remarked some weeks later that the length of the approach march had been a factor in the battle. In order to set about taking Monte Stanco, the men had to climb over broken ground in the darkness of the early morning of 13 October 1944 when the attack began. The FC/CTH started off on the right of a two-battalion attack on the mountain. The fortifications at the top of Monte Stanco were undermanned, but FC/CTH had to make three unsuccessful attacks on one strong point, which was a key enemy position, before they overcame it. After capturing Monte Stanco, the FC/CTH was ordered to resume the attack on Grizzana and Monte Pezza. The main part of the operation took three days from first thing in the morning of 13 October until late on 15 October 1944, and casualties for the FC/CTH were high. However, there was a large bag of prisoners-of-war and enemy casualties were even heavier. (Bourhill, 2011, pp 302-23; Orpen, 1970, pp 274-82; PRO WO 373/12: January 1945 official recommendation of Lt Col Angus Duncan for the award of the Distinguished Service Order). It took a further week to further consolidate the Allied positions, and to take control of Monte Salvaro.

The static winter phase

During the static winter phase of this campaign, the FC/ CTH occupied the very difficult ground that had been conquered on 15 October.

Angus Duncan established the FC/CTH headquarters at Grizzana, the village that is on the ridge of the range of mountains separating the valleys on either side, through one of which flows the Setta River, and through the other, the Reno River. The Division controlled the high ground up to the Winter Line (which ran just south of Vergato, and north of Monte Salvaro to Gardaletta). But, beyond that line, Monte Sole and Monte Caprara were still firmly in German hands, as was the town of Vergato in the valley. The German guns in Vergato had clear sight of the road running along the high ridge between Grizzana and Stanco, and any vehicle traffic on this road (known as the 'Mad Mile') had to run the gauntlet. The Germans effectively blocked any reasonable approach to a crossing of the River Reno, and had closed the road to Bologna through Vergato. They retained a foothold east of the river for offensive action against the South Africans.

Throughout the mud and slush of Autumn and the ice and snow of Winter, the battalion occupied this no-man's-land, and faced sporadic shelling and mortaring. Angus Duncan was awarded the DSO for a combination of his leadership at Monte Stanco - 'his handling of the battalion in this battle was characterized by real fortitude, courage and determination in the face of setbacks' - and his 'personal example of devotion to duty, his energetic interest in the care and welfare of his men and his outstanding military and personal qualities', which had been 'almost entirely responsible for the ... high state of morale and health in his battalion and for the complete domination by his battalion of the no-man's-land that he guards' (PRO WO 373/12: January 1945 official recommendation of Lt Col Angus Duncan for the award of the Distinguished Service Order).

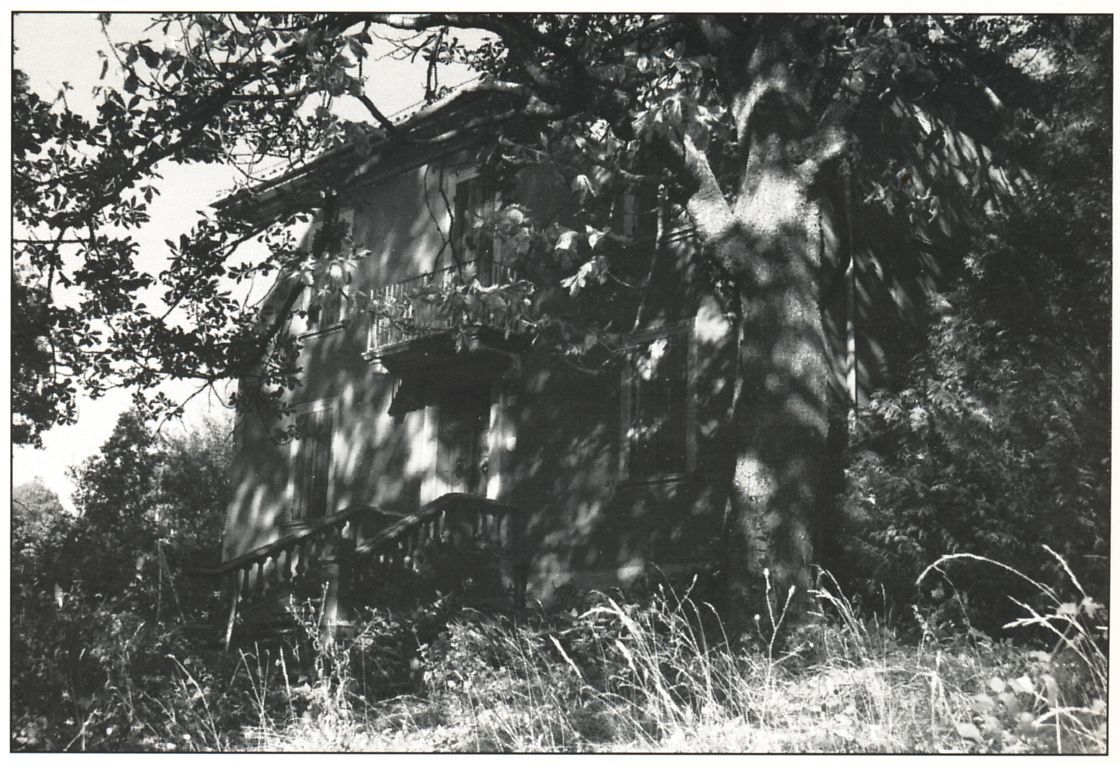

It was after the taking of Monte Stanco, and during this static winter phase of the campaign, that Colin Eglin joined the battalion in the Apennines. He had curtailed his studies at UCT in order to volunteer and, after training in Egypt, he had been assigned to the FC/CTH. As he had completed four years of university studies, this was felt to be sufficient qualification to be sent on a course in battlefield intelligence with a view to becoming 'D' Company's intelligence corporal. Lieutenant Basil Crisp was the regiment's Intelligence Officer, and each company had an intelligence corporal. Eglin was taken to the 'Pink House' near Grizzana, a farm building that was the operational HQ of 'C' Company, commanded by Major Lionel Murray. (The Villa Rosa (or 'Pink House') is still in situ on the righthand side of the road, leading out of Grizzana towards Campiaro and Vergato. Regrettably it is today unoccupied, being the subject of a long-standing inheritance dispute). There he had an intensive two weeks of training, and was taught about the terrain and the enemy disposition, before the rest of 'D' Company joined the Winter Line. Colin Eglin then joined the newly arrived 'D' Company, commanded by Major Gerry Boland. (The account of this phase is drawn from Eglin, 2007, pp 19-23; also personal communication with Colin Eglin; also Orpen, 1970, pp 283-9).

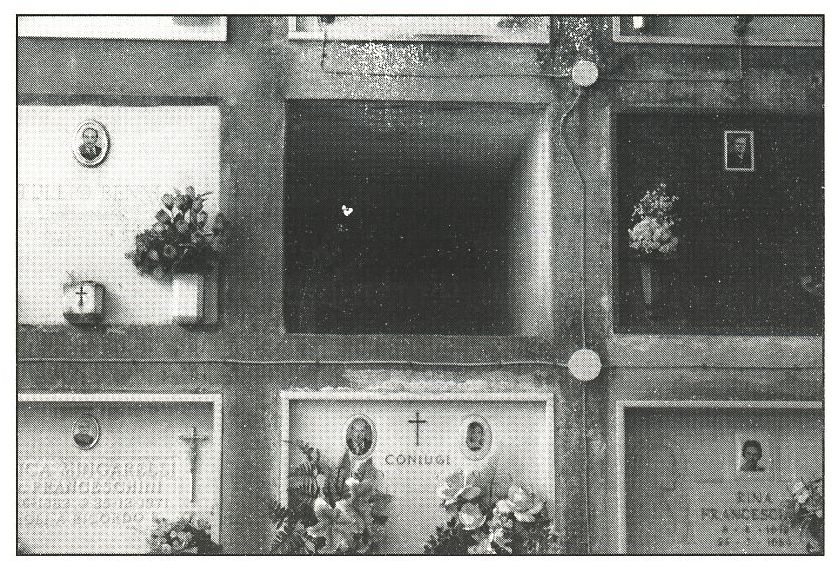

'D' Company had its headquarters in a cluster of farmhouses, named the 'Foxhole', on the slopes of the mountain overlooking Grizzana. Here the windows facing the enemy line had to be kept shuttered to avoid attracting attention. Fires could not be lit that would emit smoke during daylight. At night, Colin was one of eight who took turns to man a forward observation post at the cemetery at Campiaro, which occupied a commanding position on the side of the mountain, looking towards the ghost town of Vergato, which remained the nerve centre of the German defences. When not on guard duty, the soldiers were happy to shelter in somewhat macabre 'sleeping quarters'. There were several unoccupied loculo (alcoves ready to have coffins slid into them), which, for the time being, were empty, warm and dry. The soldiers had supplies of warm clothing, including duffel coats and white-hooded overalls, for when they were in forward positions, but often the only way to keep warm was to soak up the warmth of the exhaust behind a Sherman tank, which was kept running behind a farmhouse to recharge its batteries. The men had to endure great hardship while on the frontline, in consistently bad weather with their boots and clothing soaked for days on end. Each night, patrols went out and often bumped into the enemy who reacted fiercely. Colin became adept at map reading and at recognising, and noting, the sounds and sights of warfare. All information was passed onto patrols as they went out, and debriefings captured further information on their return. A regular break in the monotony of observation, patrols, and survival in the cold, was the two-weekly visit the men were able to make to 'Castig' for showers, fresh clothes and relaxation away from the frontline. A great meeting place for the soldiers was the iconic tower, La Torretta, in the centre of town.

In the middle of this miserable 'static winter phase' of operations, from his HQ in Grizzana, Lt Col Angus Duncan found time to write a letter to friends who had lost a son, a man at least ten years younger than him, who had been to the same school in the Cape and who had also served under him in the FC/CTH. In the course of that letter, Duncan wrote: ' ... If we are lucky enough to survive, then we shall keep faith with those who are gone by seeing that the ideals for which we have all fought are placed again high before the world - and by doing whatever each of us can to help all the peoples of the world to a sane and happy way of living. Out of all this evil we shall and must make good come ... Be happy that in his generation again the cynics are confounded. There are people in the world who value ideals more than themselves - millions of them!' (Letter from Lt Col Angus Duncan to the parents of Lt George Alexander, of the Black Watch, who was killed in action in Italy on 12 November 1944, aged 24, published as part of Angus' obituary in the Bishops school magazine in June 1945, and again in September 1946).

These are the words of a man who still held firm to the same ideals he had valued at the outset of the war, and which had driven him to volunteer at the first opportunity. It may be difficult for a large number of us now to empathize fully with this taut masculine prose, which speaks of noble self-sacrifice, suited to what we may now regard as an earlier age of chivalry. However, these words undoubtedly still resonate with the Italian people in the valleys around Monte Sole, which had been the main operational base of the Stella Rossa, the partisan brigade who engaged in sabotage and ambush of the German troops in the Autumn of 1944. To ensure control of the area between 29 September and 5 October 1944, the German army embarked on an operation designed to wipe out Stella Rossa and the Monte Sole population. The town of Marzabotto alone commemorates the massacre of 770 individuals, mostly women, elderly people and children. The brutality of the German attack on both partisans and civilians in the area caused the Stella Rossa to leave Monte Sole. (For visitors who want to find out about these tragic massacres, a tour or walk in the Parco Storico di Monte Sole is recommended. There is a network of paths, including some that are central to the tale of the battle itself, but mainly these paths lead one through the web of tragedy of the massacres: Each house and ruined church has its story, which is explained on the information panels at each site. The memorial on top of Monte Sole itself commemorates the Stella Rossa and those who died in the massacres).

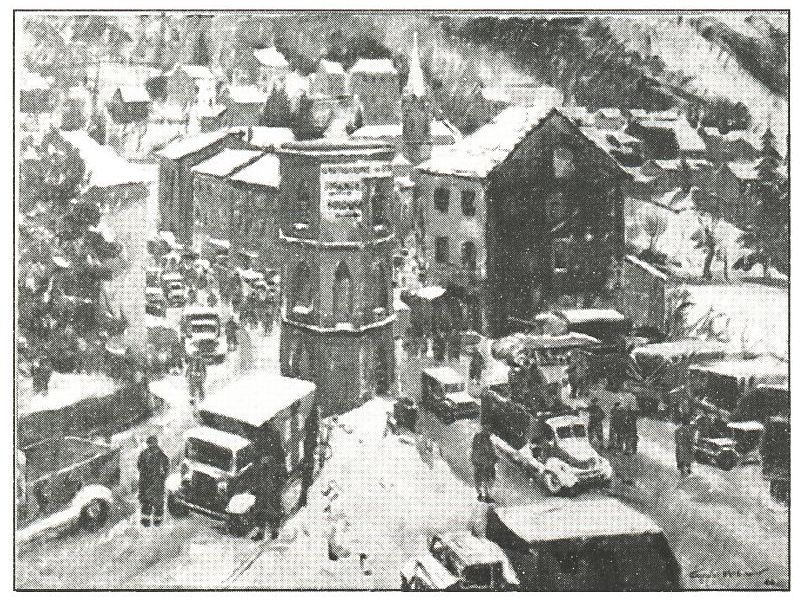

During the period 4-5 November there was an improvement in the weather but it brought with it enemy bombardment and a direct hit on the roof of the FC/CTH HQ. The ceiling of the Operations Room collapsed, covering Lt Col Duncan's staff with soot and brickdust. The routine of regular patrols and observation, relieved only by periods of 'rest' in Castig, continued for the men. Ruined houses offered some shelter for the troops, but, as the Germans had active observation posts overlooking the South African positions, care had to be taken that no house showed any sign of habitation, or it would be bombarded.

An unusual visitor to the frontline in December 1944/ January 1945 was the South African photographer, Constance Stuart Larrabee. She was the first South African woman war correspondent and documented the devastation of war through her images of soldiers and war-torn cities. She had only her Rolleiflex camera and eighteen rolls of undeveloped film when she arrived in Europe, but, with this rationed supply, produced memorable images, depicting the dignity of the individuals, the morality of the struggle and the human costs of the war. Larrabee worked for the magazine, Libertas, and subsequently published 'Jeep Trek' in the Spotlight magazine in 1946, giving her personal account of the war. Her journal captured some of the atmosphere that she encountered:

Between mid-December 1944 and mid-January 1945, she was in the static front in Italy. She recorded how the army was hampered by the isolation of the mountain villages and by the mud, snow, and incredible cold. She saw how the men lived on the mountaintops in small, cold, muddy, dank dug-outs. On 20 December 1944, she visited the 6th South African Armoured Division Cemetery in Castiglione dei Pepoli, where two of her friends lay buried, and recorded: 'I slid most of the way in the mud, walking down to their plots. A padre moved past me in silence through the gray mist ... to bury another casualty. Five Italian gravediggers and I were the only mourners ... '

On 3 April 1945 Colin Eglin was told to join a party that went ahead of the regiment to La Quercia, below the massif of Monte Sole. There, he wrote, 'Colonel Angus Duncan took us into a casa for a briefing, crisp and to the point. In a few weeks' time the Allied spring offensive would commence. The Sixth Armoured Division had been given the task of opening the road to Bologna. To do this, the Twelfth Brigade would have to capture the mountain massif formed by Monte Sole, Caprara and Abelle. The Highlanders had been assigned to capture Monte Sole. Suddenly that mountain we had gazed at all winter from a safe distance was in front of us. Forbidding, frightening, challenging. Casualties were likely to be heavy. Yet there was a sense of pride that our regiment had been chosen for this pivotal battle task, and quiet determination to show we could do it.' (Eglin, 2007, p 23). Colin recalled that Angus Duncan was a charismatic leader, who naturally took control of a briefing room, and was a 'cut above' the other officers around him.

The breakthrough and attack on Monte Sole

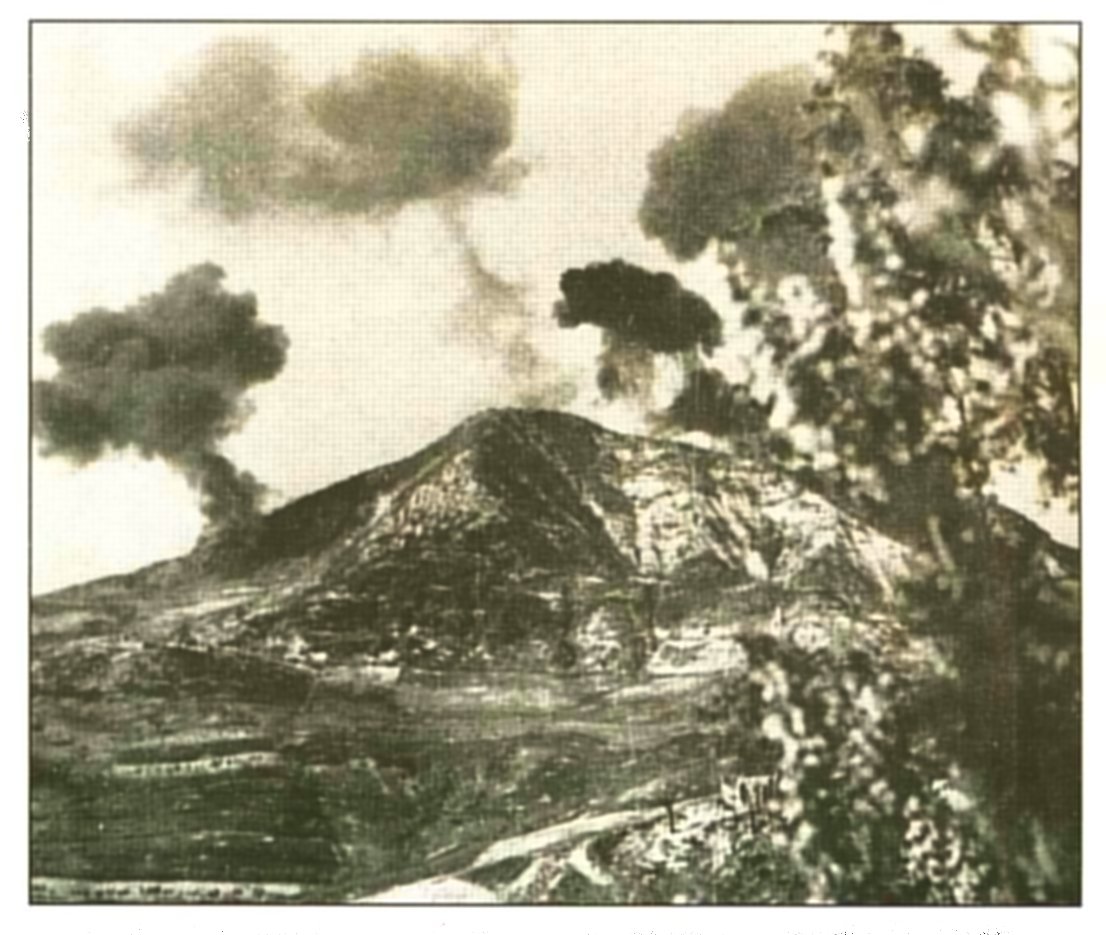

It was to be up to the FC/CTH to take Monte Sole (one of the most formidable of the enemy's defended positions), whilst the WR/DLR had, as its objective, the taking of Monte Caprara. This was a 'set-piece' action that was programmed and planned over the four months of the 'static winter phase' that had preceded it, part of the overall plan to capture the crossings of the River Po and push forward into the valley beyond the mountains. There was a massive preparatory bombardment between 8 and 16 April 1945. This involved high trajectory dropping of shells on the back of Monte Sole, where the main German defensive positions were situated. The top of Monte Sole itself was simply a small plateau. On 13 April, aircraft bombarded enemy communications and reserve positions between Vado and Bologna, as well as bridges across the Reno and the Setta. On 15 April, heavy bombers bombed the well dug-in defences on Monte Caprara and Monte Sale. This air attack was followed by a huge and concentrated artillery attack on the enemy positions. This preparatory bombardment is described by Bourhill (2011, pp 375-6).

In taking Caprara, the WR/DLR suffered casualties right at the start line, but the crest of the mountain was taken in a battle which involved hand-to-hand combat. Counter-attacks were subsequently effectively fought off.

The assembly point for the imminent FC/CTH attack was Casa Belvedere, about 2 km due south of the summit of Monte Sole, where the South Africans took over from the Americans and lay up until they received the order to start the attack. (For the purpose of this article, only that part of the action relevant to Lt Col Duncan's story is described below. More detailed accounts of the battle are available in James Bourhill, 2011, pp 375422, and Neil Orpen, 1970, pp 300-6).

After receiving their orders, 'C' and 'D' companies moved forward along two farm tracks which led to Monte Sole. One track led up the left-hand side of the ridge to Casa Casetta and, beyond that, to the cemetery (Cimitero di Casaglia). The other track led up the right-hand side of the ridge, joining the left-hand track at Casa Casetta. In the area between Casa Casetta and the Casaglia Cemetery, the two companies laid up, waiting for the final assault. This assembly point was about 900 yards (822 metres) south of the crest of Monte Sole, and the approach to the crest, which led along a single steep razor-backed ridge, was thickly mined. It was Second-Lieutenant Gordon Mollett who led the charge up the approach with five men, through the last minefield without waiting for it to be cleared, 'with total disregard for his life', and wiped out the machine gun posts of Monte Sole. With the loss of one man, he reached the summit just before 01.00 on the morning of 16 April. Mollett was not yet 20 years old and this was his first action as he had only been in the line for some twelve days, having been recently commissioned. The Germans were still coming out of their deep shelters as his little band overran their first positions with bayonets and grenades. He was awarded an immediate DSO for his bravery. Mollett's men were followed by more men of 'C' and 'D' companies. By 05.00 the entire summit was firmly in the hands of FC/CTH, they were consolidating their positions, and elements of the regiment were feeling their way down the northern slopes of Monte Sole, tackling the remaining enemy positions in dugouts and trenches.

On our visit to the site together, Colin Eglin explained to me that his task before the battle had been to install telephone lines as far up the route as possible. On his way up Monte Sole that morning, and on the track just short of Casa Casetta, the soldier walking just behind him trod on a Schuh mine, and part of his foot was blown off. Eglin had to apply a field dressing, administer first aid and call for a stretcher-bearer. It was difficult to decide then whether or not to move forward, but forward it had to be, and a couple of 'D' Company platoons continued up the spine to the summit. Eglin managed to get to the top with his field radio, but there a piece of shrapnel snapped the aerial off his radio, so he scrambled down to the headquarters' dugout. It was at the dugout that he heard, on the set tuned to Regimental HQ, that Lt Col Duncan had been killed: 'Sunray is dead, Sunray is dead. Sholto Douglas has taken over as sunray'. In the early hours of the morning, Angus Duncan had decided to go forward himself to see what should be done to attain the next objectives. On the way up to the foot of Monte Sole, passing Casa Pudella, one of his party trod on a lethal 'S' mine. Angus and his jeep driver were killed immediately and Basil Crisp, his Intelligence Officer, who was in the back of the jeep, was severely wounded. A medical jeep driver beside him was also killed.

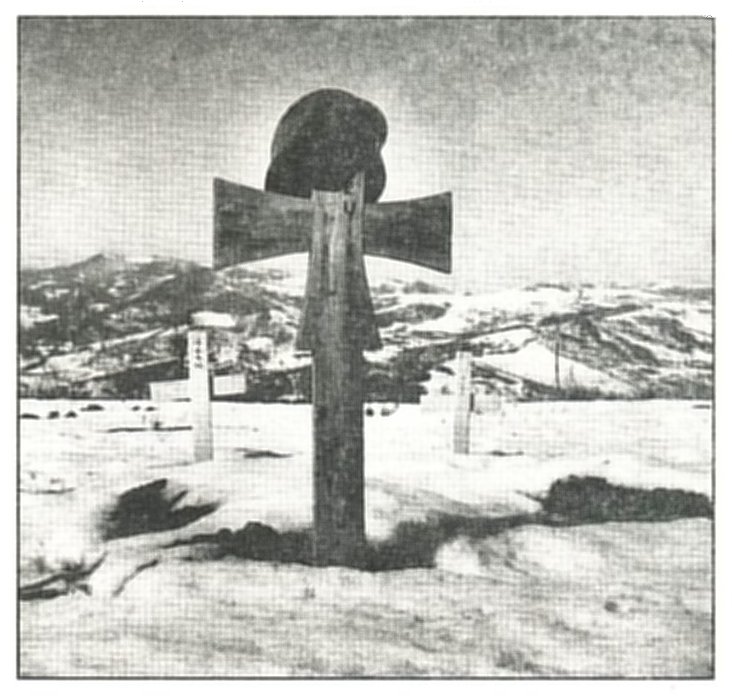

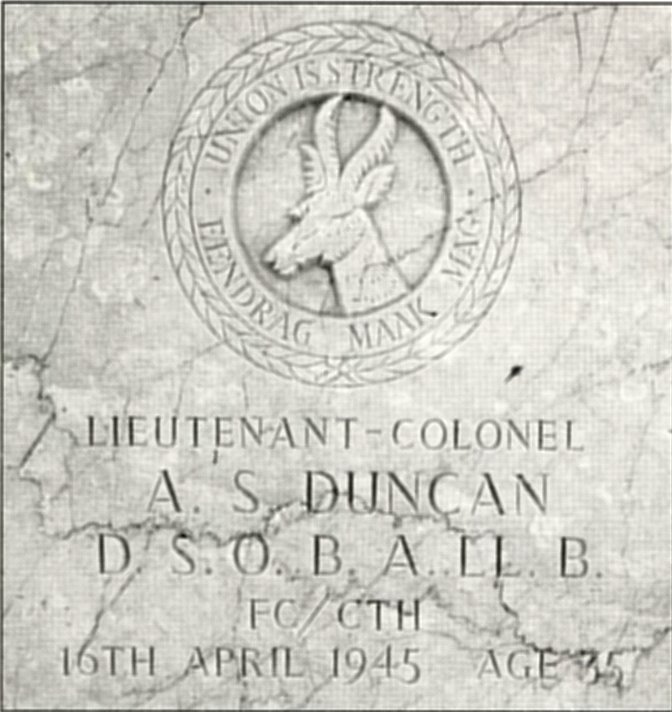

Angus Duncan was buried in the cemetery in Castiglione, with the two jeep drivers on either side of him. (This description of how Angus Duncan died is based on an extract from a letter of a senior brother officer - possibly Lionel Murray - to his Wife, which is quoted in his obituary, published in the Bishops school magazine in June 1945. In the Castiglione Cemetery today, Angus Duncan's headstone is flanked by those of two younger men of FC/CTH, who had died on the same day - pte D Acutt, aged 25, and pte C Hancke, aged 24 - so it is a fair assumption that they may be the two jeep drivers killed at the same time.)

Colin Eglin recalled the unexpected impact of the strain of the battle on two very different soldier colleagues: One, Jan, was a tough outdoors man who had seemed to relish army life prior to the battle; the other, Peter, a pale indoors man, had appeared simply to endure it out of a sense of duty. However, during the battle itself, it was Jan whose nerves snapped, and who had to be ordered to quit the battle zone. In contrast, Colin had found Peter some time later still in his slit trench that had been under intense mortar fire during a number of German counter-attacks. There he had remained, exhausted but cheerful, and he shouted across at Colin triumphantly, 'Corporal, we made it!'

Again the FC/CTH suffered heavy losses during the battle: a total of 31 men killed, and 78 men wounded. The contribution of the regiment during the battle was recognised by the granting of no fewer than twelve gallantry medals and awards.

Today Castiglione dei Pepoli Cemetery is a peaceful spot on the edge of the town, amid green lawns and trees, with the valley in the backdrop. Recounting his trip back to Italy many years previously, Lionel Wulfsohn (Military History Journal Vol 8, No 3, June 1990) quoted from his diary notes of 1958: 'As I walked through our cemetery, I felt goose-flesh on my arms and legs as I read the names of men from my section, platoon and regiment who are buried here. Afterwards, sitting under a tall shady tree overlooking the beautiful Brasimone valley, a cool breeze is blowing gently in the trees, and birds are twittering in the orchards nearby. The dappled patchwork quilt of this scene has a beauty I have not seen anywhere else in Italy. Our chaps rest gently on this lovely slope which shall forever be a piece of South Africa.' Four hundred South Africans, who died between September 1944 and April 1945, are buried in this cemetery.

The capture of Monte Sole and Caprara, coupled with the capture of Monte Abelle by 'A' and 'B' companies, FC/ CTH, contributed to the breaking of the block on the route through to Bologna, and beyond to the Po Valley. Within a matter of two weeks or so, on 2 May 1945, the Germans had surrendered in Italy. In his military memoirs, US General Mark Clark gave his verdict on the 6th SA Armoured Division: This unit...had performed splendidly under adverse conditions. It was a battle-wise outfit, bold and aggressive against the enemy and willing to do whatever job was necessary. In fact, after a period of day-and-night fighting, the Sixth had, in an emergency, gone into the line as infantrymen. When the snow stalled their armour, they dug in their tanks and used them as artillery to make up for our shortage of heavy guns ... Their attacks against strongly organised German positions were made with great elan and without regard for casualties. Despite their comparatively small numbers, they never complained about losses' (Extract from Gen Mark Clark, Calculated Risk [1956], p 379 quoted by Major A B Theunissen, Military History Journal Vol 9 No 5, June 1994).

In a letter written very close to his death in early 1945 (published in the Bishops school magazine, September 1946), there is another glimpse of Angus Duncan, a man of ideals. His thoughts were of his three children: 'The thought of them makes all this seem purposeful and easier to bear with sanity. In this crazy world of slaughter and destruction one clings hard to one's ideals-they are the only things which enable one to reduce Insanity Fair to some form. The lovely things of life, and the grand people one has met, make all this sacrifice seem worthwhile ... While there are such folk in the world there is good hope that we shall sort all this mess out into a really good pattern of living. And so we shall!'

Bibliography

Bourhill, James, Come back to Portofino (30° South Publishers, 2011).

Cros, Jack, War in Italy: With the South Africans from Taranto to the Alps (Ashanti Publishing, 1992).

Eglin, Colin, Crossing the Borders of Power: the memoirs of Colin Eglin (Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2007).

Larrabee, Constance Stuart, WW II Photo Journal (The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC, 1989).

Public Record Office, Ref WO 373/12: January 1945 Recommendation of Lt Col Angus Duncan for the award of the Distinguished Service Order.

Orpen, Neil, The Cape Town Highlanders 1885-1970 (The Cape Town Highlanders History Committee, Cape Town, 1970).

Theunissen, Major A B, 'Major-General W H Evered Poole, CB, CBE, DSO, 1902-1969: Personal Retrospects' in Military History Journal , Vol 9 No 5, June 1994.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org