The South African

The South African

South Africa is economically and strategically a maritime nation, or, to put it more accurately, South Africa should be a maritime nation. The challenge here is that few South Africans are aware of how dependent we are on the sea. One result of this has been the neglect of the Navy during most of South Africa's history and the equal neglect of the maritime elements of the South African Air Force.

At the economic level, South Africa depends on maritime trade for some 50% of the GDP, to which must be added the fishing industry, offshore gas fields and offshore diamond mining. In addition to that, most of our transport system depends on oil imported by sea. Thus, South Africa's economic dependence on the sea increases to 70% or more. At a strategic level, the key issue is twofold, one aspect being the protection of our maritime trade and assets, the second the fact that any serious military threat to the region would have to arrive by sea. In fact, South Africa's economic future is inextricably intertwined with the development of southern or even sub-equatorial Africa, and all of those countries are or will be as dependent on maritime trade, fishing and offshore gas and oil as is South Africa.

While the importance of the sea should be quite clear, the threats may be less so. These range from illegal fishing, which not only robs the country of income but also damages stocks for the future, to the risk of piracy and maritime terrorism. Should piracy become established in the Mozambique Channel, for example, this would not only increase the cost of our imports and exports, but would also severely hamper Mozambique's economic development, with a knock-on effect to be expected on our own economy - 'paupers make bad neighbours', Sergio Vieira, former intelligence official in Mozambique, once pointed out. Tanzania and Madagascar are also at risk. We must also not overlook the risk to the region of a maritime terrorist attack (such as that at Mumbai in 2008), of maritime guerrilla operations (such as those conducted by Sri Lanka's 'Sea Tigers' for many years), and of the abduction by sea of tourists (as has happened in Kenya) and the impact of these on the currently lucrative - and potentially much more lucrative - tourism industry of the region. The rise of piracy and maritime terrorism also threatens South Africa's acquisition of oil from West Africa and her trade with West African nations generally.

Like it or not, what goes on out at sea is of real concern to all of us, even those living at the rarified altitudes of the national business and political capitals.

A regional maritime security role

Having accepted the importance of the sea, we also need to understand that South Africa is one of the few countries south of the Sahara with a serious navy. Within the SADC region, only Namibia and Tanzania have navies capable of any real patrol activity, and the latter is hampered by its very old and small vessels. Further north things look a little better, with Nigeria and several other countries investing in their navies, but most of them too poor to develop more than a coastal capability. On the east coast, Kenya has a small but professional navy, but it is challenged by the situation in Somalia.

With the South African economy being by far the largest in Africa (25% of the total, 35% of the sub-Saharan economy) and the 27th largest in the world, there is an expectation that South Africa will take on an expanding regional maritime security role. This is already there to be seen in the Tripartite Memorandum of Understanding between South Africa, Mozambique and Tanzania. In terms of the MoU, the Navy has a ship more or less permanently patrolling in the Mozambique Channel, and there is more to come, following, for instance, the signing in March 2013 of the Benguela Current Convention, which calls for patrolling.

These obligations present the South African Navy with the difficult challenge of taking on an expanding regional maritime security role with a fleet that is too small, a budget at least 30% below what is needed to function effectively even at its current strength, and its smaller vessels needing replacement very urgently indeed.

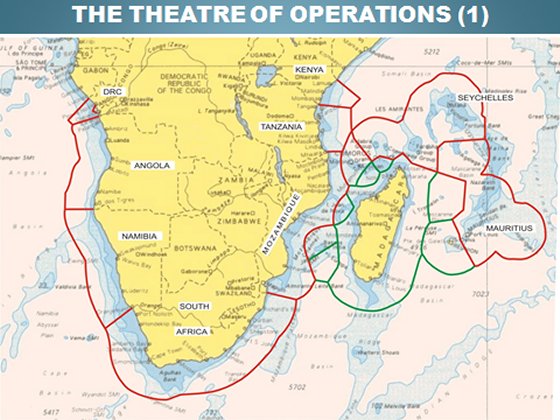

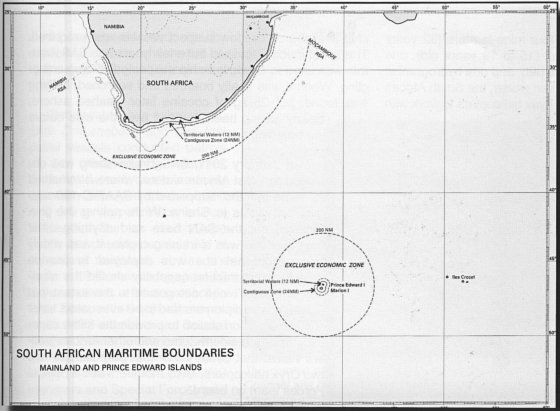

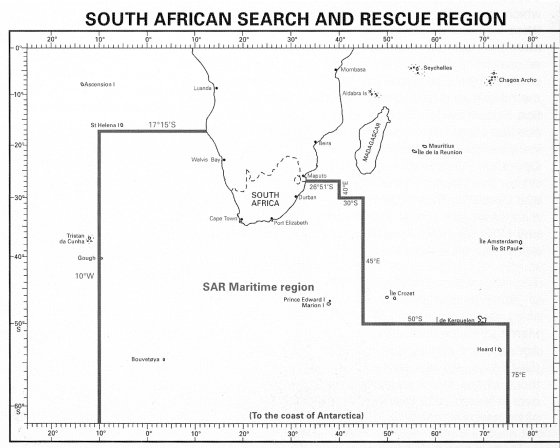

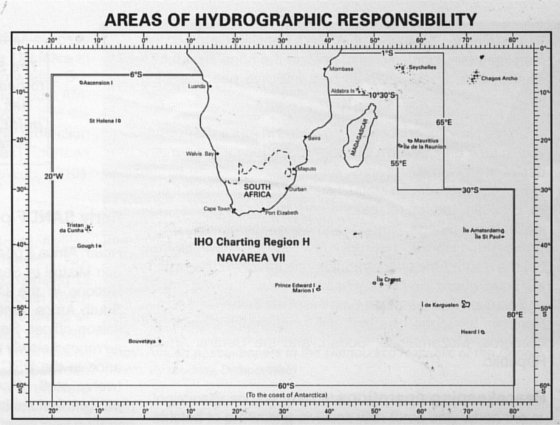

To place the responsibility versus resources mismatch in perspective: South Africa has a 2 798 km coastline and a 1,54 million km2 Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which includes Marion and Prince Edward Islands, 1 000 nm south-east of the mainland. The SADC as a whole has a coastline of some 15 000 km and combined EEZs of some 9,16 million km2. In practical terms, one should add Kenya, which has no stable maritime neighbour other than the SADC, and the Comoros, which lie within the broad SADC maritime zone, bringing the total to 9,5 million km2, stretching far eastward into the Indian Ocean. Within this area lie two maritime choke points (the Cape of Good Hope and the Mozambique Channel), shipping routes vital to South Africa and the region, important offshore gas and oil fields, fishing grounds and an offshore diamond mining industry. Of course, the actual area to be protected is much larger than the combined EEZs of the SADC states - shipping routes do not all lie conveniently within these; nor do pirates attack only within those waters, as Somali pirates routinely demonstrate in the Indian Ocean.

The Fleet

The fleet with which the SA Navy must take on this security task is miniscule and half of it is seriously aging. It comprises four frigates (7 to 8 years old), three patrol submarines (4 to 6 years old), four fast patrol craft (28-32 year-old former strike craft), four mine-hunters (32 years old), three inshore patrol craft (15 to 19 years old), one combat support ship (25 years old), and one hydrographic survey ship (41 years old). Even worse, the South African Air Force has only four Super Lynx helicopters to work with the frigates, when a frigate deployed as a singleton should embark two, and is forced to use 70 year-old Dakotas as maritime surveillance aircraft to support the fleet.

Operations

The small South African fleet has been very busy over the past few years with operations and exercises with other navies. Current and recent operations include: Operation Copper, the anti-piracy patrol in the Mozambique Channel, which has seen a frigate or SAS Drakensberg deployed there for most of the year, and also at least one deployment by a submarine to carry out mainly nocturnal reconnaissance of islands where pirates might have temporary shore camps; Operation Corona, routine coastal patrols by the mine-hunter SAS Umzimkulu and the Maritime Reaction Squadron (MRS); Operation Prosper, providing support for the police as required, for instance during the BRICS summit; Operation Phefo, maritime security during the African Cup of Nations; and Operation Chariot, the deployment of an operational diving team and MRS elements to aid Mozambique after the floods.

The Navy also carried out 31 days of fisheries patrols with its own ships between June 2012 and March 2013 for the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), as well as 84 days using those of the DAFF vessels taken over in March 2012 that were actually seaworthy.

There is also a standing arrangement, Operation Wallow, to make a ship available to shadow suspect vessels when required. This is not much discussed but a few years ago SAS Amatola was used to shadow a ship suspected of drug smuggling. When it was finally boarded and searched, nothing was found, but 25 kg of cocaine later washed ashore, clearly having been dumped over the side before the boarding.

In January 2011, SAS Drakensberg was deployed to West African waters, where it remained for three months, supported by SAAF C-130 sustainment flights to Ghana. While neither the government nor the SAN have said anything other than that this was a training" cruise, it was widely understood that she was deployed to provide emergency extraction capability should the situation in Cote d'Ivoire deteriorate to the extent that South African diplomats had to be evacuated. Later she remained on station to provide the same capability when President Zuma and other African leaders visited that country. For that purpose she had two Oryx helicopters, MRS members and a Special Forces team on board.

In May 2011 SAS Isandlwana departed Simon's Town on 4 May 2011 to make a high speed run to Tristan da Cunha, to evacuate fishermen who had been injured in a shipboard gas explosion. She used her Super Lynx to lift off the worst injured of the fishermen, and then made another high-speed run to Cape Town, where the patients were landed on 12 May.

Both operations were in addition to the Mozambique Channel patrol, routine patrols of South African waters and various exercises.

In 2010 the World Cup presented the Navy with an entirely different challenge as part of the wider security operation around that event, Operation Kgwele. The Navy had more than 1 000 of its members deployed for that operation, at sea and ashore, the latter including provision of MRS members for port security, more than 1 600 dives by the Operational Diving Teams to check where cruise liners would be moored, and standby capability in case of terrorist attack using biological or chemical agents.

Two frigates, two submarines, SAS Drakensberg and two fast patrol vessels conducted patrols off the cities hosting matches; SAS Protea and two mine-hunters were deployed as command and diving support ships in Port Elizabeth, Durban and Cape Town; and one frigate was held at immediate readiness in Simon's Town. SAS Drakensberg spent 50 days at sea as a floating reaction force base, with Oryx helicopters, boats, MRS elements and Special Forces teams embarked, while the frigates provided radar coverage and had Super Lynx, MRS members and Special Forces personnel on board.

Other operations during 2010 included an extended patrol of the waters of Marion and Prince Edward islands by a submarine, the aim being to build an intelligence picture of the fishing activity there, and inshore operations in support of fisheries' inspectors and the police working to suppress the poaching of abalone.

Exercises

Training exercises are, as with all professional navies, a key element to ensuring that the fleet and its ships are actually able to perform their mission. Apart from its own annual Red Lion force preparation exercise, the Navy also participates in routine exercises with ships of other navies passing through South African waters, and in a series of regular exercises with other navies.

The major regular (generally biannual) international exercises are:

Exercise Atlasur with the navies of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, which alternates between South African and South American waters, the next in 2014 to be held in South America; Exercise Good Hope in South African waters with the German Navy and Air Force, on a three-yearly basis at present because of German operational commitments, the next due in 2015; and Exercise Ibsamar with the Brazilian and Indian navies in South African waters, with the next to be held in 2014.

Less regular but intended to be held at least biannually are Interop West and Interop East, exercises with other African navies on the western and eastern seaboard. Interop East in October 2011, for example, saw a submarine and SAS Drakensberg deploy to Tanzanian waters, joining up with Tanzanian and Kenyan ships and with Mozambican and Zimbabwean officers embarked. The same year saw the Navy help Malawi host a lake/riverine exercise (Good Tidings) on Lake Malawi. A SAAF C-130 flew a 20-strong SAN detachment with two rigid-hulled inflatable boats (RHIBs) to Malawi. Tanzania deployed a similar detachment and Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe deployed diving teams.

Smaller exercises set for the near future include two with SADC navies, Fairway Buoy and Wayside; Exercise Oxide with France and Tanzania this year and then again in 2015; Shared Accord with the United States Navy this year; and Atlantic Tidings with Angola, the DRC and Brazil. The Navy also participates in SADC Special Forces exercises when those involve a maritime element.

Fleet Status

There has been much negative media coverage of the Navy, particularly regarding the status of its ships, but much of this has been inaccurate. Nevertheless, it is certainly true that the Navy has had some rough years: It suffered major retrenchment in 1990 that cost it many of its technical staff; it lost more key personnel during the 1990s; it had to bring two classes of warships into service at the same time (which, uniquely among world navies, it managed to do more or less on time and under budget!); and then it had to take on the Mozambique Channel patrols, for which it had not made provision. The lack of planning, it must be stressed, cannot be blamed on the Navy: Advisers to the Defence Ministry in the 1990s kept insisting that South Africa should not operate 'out of area' or even have any real capability to do so. Hence, the Navy had only four frigates instead of at least six, insufficient planned sea days to allow for out of area patrols, and only one support ship. One result has been the over-stretching the frigate force - too many sea days and delayed maintenance periods - with the inevitable outcome of technical problems.

It must also be said that 'affirmative action' and 'fast tracking' of personnel played their role, causing, on the one hand, an outflow of experienced personnel who saw no service future in the Navy and, on the other, too-fast promotion of black ratings and officers who had yet to gain the experience necessary for their new posts and ranks. It will take some time to work this problem out of the Navy, but, if the standard of our junior officers is something to go by, it should not take much longer - there are some very serious and professional mariners there.

The status of the fleet today

Of the four frigates, SAS Amatola is deployed in the Mozambique Channel (albeit using only a single diesel engine and the gas turbine as needed); SAS Spioenkop is working up to taking her place on that patrol; SAS Isandlwana is undergoing a 'docking and essential defects' (DED) period, has received a replacement diesel engine and should be operational again in July; and SAS Mendi is preparing for her refit. The Navy is also engaged in planning a 'spiral upgrade' programme for these ships, an early element of which has seen the ships receiving two close-in weapons mountings for their new anti-piracy role, One problem being experienced with their refits is the long lead time involved in obtaining foreigtn-sourced spares, not least because of a cumbersome procurement system. Another reason for this has been that Armscor has not been able to effect the Dockyard turn-around as had been hoped.

Of the three submarines, SAS Charlotte Maxeke is operational; SAS Queen Modjadji II is in short-term maintenance and training crew, and is available at reasonably short notice if she is needed; and SAS Manthatisi is in refit until August 2014 after which Charlotte Maxeke will go into dockyard hands for her first refit. Looking forward, the Navy is planning to have two of the three boats operational at most times. Given that it is already doing rather better than at the business of keeping submarines operational than Australia (2 out of 6 some of the time), Canada (1 out of 4 some of the time), and the Royal Navy (1 out of 5 attack submarines), this seems to be a perfectly reasonable expectation. One planned upgrade is the acquisition of two new torpedoes as funding allows.

Of the four former strike craft now employed as patrol vessels, SAS Galeshewe is operational and conducting Operation Corona patrols; SAS Isaac Dyobha is in short-term maintenance and available if needed; SAS Makhanda is undergoing refit in Durban and SAS Adam Kok is pending refit. The refit of these very elderly vessels is intended to keep them operational for about five more years, by which time the Navy hopes to have its new offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) coming into service.

The four old mine-hunters are now all only used for inshore patrols and training, their mine-hunting systems being long outdated. SAS Umhloti and SAS Umzimkulu are operational and used for training and Operation Corona patrols; SAS Umkomaas is undergoing a maintenance period; and SAS Umgeni is in refit. These vessels will also be replaced by the future OPVs. As regards their previous mine-countermeasures (MCM) role, this is currently handled by a single shallow-water route survey system, but there is a project to acquire a new MCM system that will be deployable aboard the OPVs and from shore.

The hydrographic survey ship, SAS Protea has recently completed a modernisation period and is back in service, together with two survey launches for inshore work and a mobile team to work ashore. Her one weakness is that she cannot accommodate any of the new helicopters to take the place of the Alouette III previously used to place shore markers and for similar tasks. A replacement for this elderly lady is already being planned, and should be available in the not too distant future.

Finally, the combat support ship, SAS Drakensberg will be undergoing a ship life-extension programme (SLEP) and then return to service around May 2014.

Future Plans

Planning has long been difficult for the Navy, with funding tight and frequent cuts of what funding it has. What does seem firm at the moment is the project to acquire a number of offshore patrol vessels - eight if funding allows - to patrol home waters and to take on some of the future regional work. The concept is to have four of these ships deployed at anyone time, two in training or maintenance but available when needed, and two in refit. Assuming this is given the go-ahead - and soon - it will take the pressure off the frigate force and provide the country with a reasonably balanced surface fleet. The one remaining immediate gap then would be a second combat support ship, but that is on the table as far as the Navy's planners are concerned, assuming again that funds can be prised out of the Treasury.

On the support side, the Navy is bringing Naval Station Durban back to Naval Base status and will re-establish naval stations on those major ports that no longer have them. The Navy is also intent on rejuvenating its reserve component, which will play a major role here.

This leaves one major question unanswered: Will the Air Force finally, after almost thirty years of dithering, become serious about acquiring maritime surveillance or patrol aircraft and, for that matter, helicopters for the future OPVs? If not, perhaps that role and the funding for it should be transferred to the Navy as part of an overall maritime programme.

Helmoed Römer Heitman is a defence analyst and author.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org