The South African

The South African

The subject of the Natal Volunteers - who they were, what they achieved, and how they were armed is vast. Only parts of this field have been adequately, documented. What follows is brief attempt to reiterate what is already known of their background, history and major battles but, most importantly, to also fill in some of the gaps relating to the rifles and carbines they used. This will hopefully set the scene for further research.

The 'Volunteer' military unit has always had a number of characteristics, such as freedom of choice, a body other than the regular army and a time of need. In the crown colony of Natal this need for a Volunteer force arose in 1853 when the Crimean War resulted in Britain thinning down both garrisons and expenditure. The warlike Zulu nation lay just across the border, the colonists felt exposed and the Colonial Government was also too short of funds to support a standing military force. Volunteer units were the answer. Here two major influences were the Volunteer rifle movement which flourished in England and the Empire in that era and also the commando system common to Natal's Boer neighbours.

To the patronising contempt of the remaining Imperial officers, the Natal Volunteer Defence Ordinance of 1854 came into being, which authorized '[t]he European inhabitants to form themselves into units with permission to elect their own officers and frame their own regulations for their discipline and control and will be liable for service when called out under the authority of the Lieutenant Governor in any part of the Colony' (Hattersley, 1950, p6). In terms of this ordinance, the men had to provide their own horses, saddlery and uniforms while the Government supplied arms and ammunition.

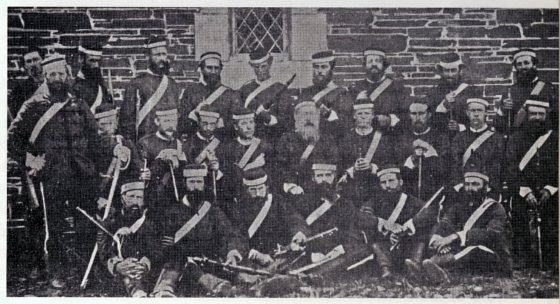

Amongst the first regiments to be raised in 1854 and early 1855 were the Durban Rangers, the Durban Volunteer Guard and the Pietermaritzburg Light Horse (shortly to be renamed the Natal Carbineers). All subsequently became 'Royal'. There was a strong social function to the Volunteer units in Natal. Many of the colonists were ex-military men who missed the comradeship of arms, or who lived on remote farms and lacked a social life. Such men were glad to unite under the Union Jack while attending their quarterly shoots and annual camps. Initially the Volunteers were exclusively white, with black grooms and servants. This changed only during the emergency of the Zulu War, when large numbers of infantry, pioneers, border guards, and mounted men were recruited among loyal blacks in Natal, Basutoland and Swaziland. These units had white officers but NCOs of both races and at the outbreak of this conflict over 80% of the forces facing the Zulus were black. Following the conquest of Zululand, Natal's black units were rapidly dissolved, sadly also including those with such illustrious battle records as the Natal Native Horse.

Over the years, Volunteer units proliferated, amalgamated and disbanded as circumstances or enthusiasm dictated and by the time the Natal Volunteers, as militia, had been absorbed into the Union Defence Force in 1912 almost sixty had come into being. Others were temporarily raised to face emergencies and to these, perhaps, can be added several which were recruited in the Cape for service in Natal during times of trouble.

From 1854 to 1912 the Natal Volunteers were issued with some fourteen different rifles and carbines, with periods of usage that overlapped between regiments and even platoons or troops within the units concerned. It is therefore unrealistic to cover all rifles in detail. We shall thus concentrate upon those that saw active service, merely mentioning the others in passing.

MUZZLE-LOADERS

The Pattern 1839 Musket

In the beginning and, as is often the case where governments are involved, delivery of equipment lagged behind the enthusiasm of those destined to receive it. Until April 1855 the early Natal Volunteers paraded with their own firearms. The exact nature of the first military issue is uncertain but it is understood that these firearms were passed down from the disbanded native police. Fortunately a description survives:

'The musket placed in our hands was long and heavy with a huge metal sight at the end, upon which the bayonet was twisted and held with the aid of a side spring that locked it in place .. , long-barrelled Tower Muskets with bayonets ... and caps like miniature copper hats.' (Martin, 1969, pp 8-9).

This probably refers to the .753-inch smooth bore Extra Service percussion musket of 1839 or else possibly the very similar Pattern 1842. These remained on issue until replaced by the .577-inch Enfield muzzle-loading rifle in 1860.

The Enfield Rifled Musket

A surviving Enfield, marked to the Natal Volunteers, is of the twoband 1856 Pattern, while photographs of the Natal Native Contingent records suggest that the earlier three-band P1853 Enfield rifled musket was also acquired by the Government at some stage, probably shortly prior to the Zulu War of 1879 to arm black auxiliaries. The Enfield rifle was carried by such infantry regiments as the Royal Durban Rifles until 1875 while a locally shortened version was on issue to the mounted units until replaced by the Calisher & Terry Carbine in 1863. It is believed that at least some of the accompanying sword bayonets for the Enfields were recovered from a wreck off Durban.

EARLY BREECH-LOADERS

The Calisher & Terry Carbine

The Natal Carbineers first mustered in September 1855 and, on 29 October 1860, Lieutenant-Governor Scott wrote to the Duke of Newcastle, 'urging that 250 breech-loading carbines should be issued in replacement of their largely useless shortened muskets' (Hattersley, 1950, p13). With the resulting Calisher & Terry, we have the first of the Volunteer arms to be tested in battle. This carbine, manufactured in Birmingham from 1858, was of the type known as a 'capping breechloader', which accepted a paper cartridge ignited by a percussion cap.

The breech mechanism was a primitive bolt-action with rear-locking lugs, and prone to gas leakage on firing. The bolt handle was folded down after closure, in which position its tip protected the loading port. Unfortunately, the weapon was 'cumbersome to load', an important factor in the hands of ill-trained volunteers (Coghlan, 2000, p5). The few examples surviving in Natal suggest that the carbine issued to the Mounted Volunteers was a commercial version of the second model of the Calisher & Terry dating from 1860. Those so far examined do not bear any issue markings linking them to the Natal Volunteers. This is unfortunately consistent with the Natal Government's somewhat erratic practices concerning the marking of its arms.

The Calisher Carbine's first blooding took place at the Bushman's River Pass during the Langalibalele Uprising in 1873. Here a small detachment composed of the Karkloof Carbineers, the Natal Carbineers and a number of Basuto guides under a Major Durnford were involved in the attempt to prevent the Amahlubi tribe under chief Langalibalele from leaving the Colony for Basutoland. This followed a failed attempt to disarm the tribe.

Arriving a day late in Basutoland after a harrowing climb up the almost inaccessible Hlatimba Pass, this small group of poorly trained men was enfiladed by armed Hlubi warriors who had arrived before them. A respected sergeant lost his nerve and the Hlubis opened fire. The Volunteers panicked, broke and fled back to the head of the pass.

At its head, they rallied but by then Durnford, who had been wounded, lost his resolve and they were ordered back to Natal. Three Carbineers, a guide and the interpreter lost their lives. Casualties on the side of the Hlubis were also about five, two of whom were killed by Durnford using a revolver (Pearse, 1973, p240).

Specifications of the Calisher Carbine

| Overall length: | 37.75 inches |

| Barrel length: | 20.13 inches |

| Weight: | 6 lbs 1 oz. |

| Calibre: | 0.56 in. |

| Rifling: | 5-groove, right-hand twist |

| Sighting: | Ramp & leaf, 1 000 yards |

The Snider Cavalry Carbine

In reaction to the Langalibalele Revolt, the Natal Mounted Police was formed with the first trooper being enlisted on 12 March 1874. In that month, also, their commander, Major Dartnell, wrote a letter to the Colonial Secretary which reflects significantly upon the weapons then available to the Volunteers: 'The only arms that I have been able to get for the force are six Sniders which have been handed over to me by the Volunteer Department. The same department has in store about twenty Terry rifles (which are unserviceable) and a lot of muskets and short Enfield rifles, none of which will do' (Holt, 1913, p22).

Specifications of the Snider Carbine

| Overall length: | 37.0 inches |

| Barrel length: | 19.25 inches |

| Weight: | 6 lbs 7 oz. |

| Calibre: | 0.577 in. |

| Rifling: | 5-groove, right-hand twist |

| Sighting: | 600 yards |

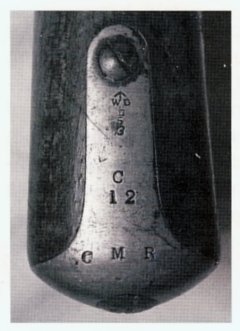

It is unclear exactly how many Snider carbines were imported after 1874 but, as the Zulu War approached, the Natal Government began to buy large quantities of arms. Major Dartnell (who by then commanded all the Volunteers) recorded that in 1878 and 1879, the Government purchased 1 340 Snider cavalry carbines from the Crown Agents and also a further 498 from the Cape Colony (Sessional Papers, Natal Legislature, p250). Significantly, as in the case of the Calisher carbines, none of the examples found in Natal today bear Natal Volunteer markings, but Cape markings are occasionally encountered. Many troopers from mounted units such as the Cape Mounted Rifles also rode north as private volunteers for the Zulu War. It is likely that they brought their own Snider cavalry carbines. Some of these may have remained, thus accounting for certain Natal finds.

MARTINI-TYPE ARMS

The Swinburn Henry Rifle and Carbine

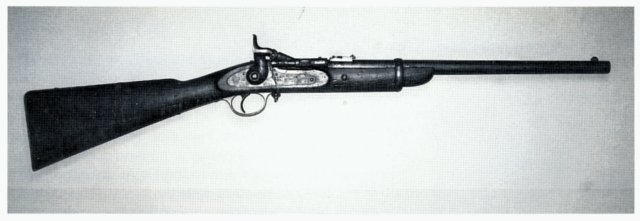

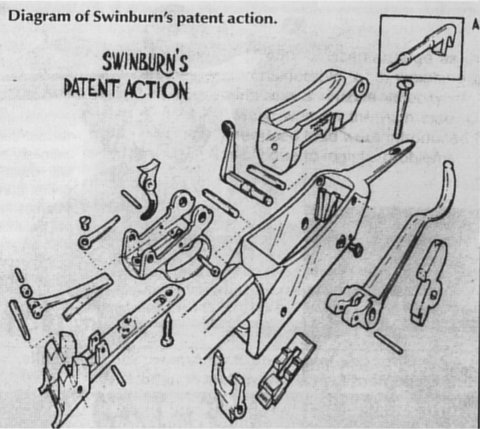

Any rifle adopted by the British Army radiated an aura of excellence, raising significant commercial possibilities for those in a position to exploit them. This resulted in a brisk trade of obsolete military rifles and in copies of those still in service. The Natal colonists and their government were obvious targets. With the advent of the Martini Henry a potential goldmine had arrived. The only problem was, of course, that Martini's patent still had a considerable time to run. One solution was a 'look-alike' which could trade on an external similarity to the military rifle but utilize an action sufficiently different to avoid inconvenient legal complications. Such a rifle was designed by J S Swinburn of Swinburn & Son, Birmingham, and manufactured by the Abingdon Gun Works. As with the Martini, the action was opened and cocked by a lever hinged to the rear of the trigger-guard which depressed a grooved breech-block to expose the chamber. Unlike the Martini, however, the Swinburn had an internal hammer activated by a v-spring at the rear of the action. Also unlike the Martini, the Swinburn butt was attached to the receiver by means of an upper and a lower tang instead of a sturdy axial bolt. This action was not as robust as that of the Martini. However, a distinct improvement over the original design was an external cocking lever on the right hand side of the action which enabled the rifleman to carry I)is weapon loaded, and cock it without having to open the breech. The Henry barrel and chamber enabled use of the .577/.450" Martini cartridge issued to the regular forces. The Swinburn Henry came in rifle and carbine versions, both of which had provision to fit a bayonet. They bear a J K L cartouche stamped into the woodwork which is believed to be that of their supplier, John Kerr of London.

Swinburn Specifications

| Rifle | Carbine | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall length: | 49.25 inches (125cm) | 39.5 inches (100cm) |

| Barrel length: | 33.25 inches (84,45cm) | 37.0 inches |

| Weight: | 9 lbs, 0 oz | 7 lbs, 2 oz |

| Calibre: | 0.577 /0.450 inches. | 37.0 inches |

| Rifling: | Henry-pattern, 7-groove, polygonal with ribbed angles & right hand twist | Henry-pattern, 7-groove, polygonal with ribbed angles & right hand twist |

| Sighting: | 1 300 yards (1 188m) | 800 yards (731 ,2m) |

Three patterns of markings are found on the Natal Swinburns, those with low serial numbers having a 'V' followed by a round stamp which is clearly a stylized Union Flag. With higher serial numbers the V is accompanied by a more commonly encountered crude sunburst stamp which was probably applied using a locally-manufactured replacement punch. Carbines issued to the Natal Mounted Police are stamped 'NMP'. Others, apart from an issue number, are unmarked. Photographic evidence suggests that these may have been issued to Imperial Mounted Infantry, war correspondents and Boers, such as Piet Uys and his sons, who accompanied the British forces. By the time the Pattern 1971 cutlass bayonets were acquired in the 1880s, the crude Union Flag was omitted and the Martini Metfords and Martini Enfields, which later replaced the Swinburns, merely exhibit a 'V' sometimes accompanied by an issue number.

As is often the case, rearmament to counter a perceived threat is a prelude to political aggression. In this case, those to be coerced were the Zulus. Minor border incidents were escalated into the justification to present the Zulu king, Cetshwayo, with an impossible ultimatum or face invasion on 11 January 1879. The invasion was entrusted to Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Thesiger (Lord Chelmsford). Chelmsford's plan of attack involved the penetration of Zululand by five columns at three points to converge upon the Zulu capital, Ulundi, thus encouraging a Zulu attack. This would, he was confident, then be annihilated by the disciplined firepower of Her Majesty's soldiers. In the absence of sufficient regular cavalry, the mounted Natal units served as scouts. As far as can be established, the Volunteers, the Mounted Police, the Natal Native Horse and white non-commissioned officers from the Natal Native Contingent were armed with Swinburn and some Snider carbines. Snider and muzzle-loading Enfield rifles, with only five rounds of ammunition per man, were issued to a tenth of the Natal Native Contingent while the rest were armed with assegais. The British Regulars were equipped with the Martini Henry rifle, which the Natal Government had been unsuccessful in obtaining for its own men.

We need only concern ourselves with the second and third columns which were ordered to enter Zululand via Rorke's Drift near the mission station of that name. The second column, reduced in numbers to three companies of the Natal Native Contingent, five troops of the Natal Native Horse and a rocket battery was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Durnford of Bushman's River fame (Morris, 1966, p327). The third, under the command of Brevet Colonel Glyn, consisted primarily of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 24th Regiment, supported by detachments from the Natal Mounted Police, the Natal Carbineers, the Newcastle Mounted Rifles, the Buffalo Border Guard and the 3rd Regiment of the Natal Native Contingent (Rothwell, 1989, p143).

Upon expiry of the ultimatum, the third column crossed the Buffalo River into Zululand and commenced the tedious haul towards Ulundi. On 20 January 1879, it arrived at the foot of a strangely shaped hill known by the locals as Isandlwana. At base of this, Lord Chelmsford established his camp and storage depot, but without laagering or creating any other form of defensive works as advised by the Boers and Colonials.

There is, unfortunately, insufficient space to fully cover the subsequent disaster and those who are interested in its finer details are referred to such sources as The Washing of the Spears by Donald Morris. Suffice it to record that on the fatal day Chelmsford divided his forces, leaving the smaller part in the camp. This included six companies of the 24th Regiment, eight of the Natal Native Contingent and about eighty Natal Volunteers from various units. The balance under his personal command set off on a wild goose chase to locate the main Zulu impi, which, unbeknown to him, was actually approaching from another direction.

Durnford was instructed to reinforce the camp with the force under his command, but upon arrival he also divided his men, sending two troops of the Natal Native Horse to reconnoitre the nearby Nqutu Plateau while, with the rest of his command, he followed Chelmsford to provide support. The scouts on the plateau soon encountered the main Zulu army of some 25 000 men resting in a valley. The Zulus attacked, streaming towards the Isandlwana camp while deploying into the traditional 'horns of the buffalo' formation to complete encirclement.

There is still controversy concerning how exactly the defending troops were positioned, but the fundamental error was made in opposing the encircling warriors not with a virtually impenetrable British square, but with adjacent companies of the 24th forming the sides an inverted 'L' protecting only the north and east of the camp while another two companies of the Natal Native Contingent formed its knuckle. Durnford retreated towards the camp, losing his rocket battery in the process, but picking up piquets of the Natal Carbineers and Newcastle Mounted Rifles on the way. With these reinforcements and his remaining two troops of the Natal Native Horse he positioned his men in a donga and with the deadly fire of their Swinburn carbines they temporarily held back the left horn of the Zulu army. Here we can hopefully lay to rest the persistent myth that the Natal Native Horse were armed with the Westley Richards MonkeyTail Carbine. A surviving black trooper recorded Durnford's inspiring leadership and also his knack of clearing jammed cartridge cases from the carbines - a problem not encountered with a capping breech-loader! (Moodie, 1988, p 43).

Inevitably, Durnford's little force ran short of ammunition. Forced to abandon their position, they then continued their withdrawal towards the camp. At this time, also, the Zulus at the centre broke through the British lines taking the companies of the 24th in the rear or following them as they retreated towards the camp. Meanwhile, the left horn, no longer opposed, continued its encirclement. Durnford, rallying a small group of the Volunteers and Mounted Police, positioned them in the saddle connecting Isandlwana and Stony Koppie in an attempt to prevent the closing of the Zulu horns. As mounted men, some could probably have escaped, but they chose instead to fight until the end and were joined by a few survivors of the 24th.

Since none lived to tell the tale, only Zulu accounts remain. At first, Durnford's men formed a hollow square, firing volleys upon Durnford's command but, as their carbine ammunition petered out, the volleys became scattered shots and the warriors moved closer, flinging assegais and firing such firearms as they had. Finally, when even their pistol ammunition was done, the few remaining Police and Volunteers formed a double line, shoulder to shoulder, and stood fighting back to back with snatched assegais, knives, fists and Swinburn carbines both clubbed and with Bowie bayonet. This could never last and according to one source, Mehlokazulu, '[t]hey died in one place all together' (Knight, 2004, p103). When the British returned during May 1879 to bury the dead, the bodies were indeed found clustered around Durnford, many with their hands scorched by the searing barrels of their overheated carbines, thus bearing witness to the desperate nature of those heroic final moments (Hattersley, 1950, p22).

At Isandlwana, the total British forces killed were 52 officers, 806 white troops, and 471 black troops (including non-combatants); the Natal Mounted Police lost 26 men and the Volunteers, 34, mostly Carbineers (Rothwell, 1989, pp 156-7). Exact Zulu losses are unknown but were probably greatly in excess of 1 000.

Editor's note: The second part of this article, and the bibliography, will appear in the next issue of the Military History Journal, Volume 16 No 1, June 2013.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org