The South African

The South African

About the author

Benjamin Brown is retired from the Foreign Service of the United States. He has served in nine countries, including South Africa. He is a graduate of Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and a United States Army veteran of the Korean War. He is the author of Imperial Colours, a dictionary of terms used to describe military uniforms with a cross-reference glossary in English, French and German.

Introduction

During the latter half of the seventeenth century, Dutch and French Huguenot emigrants arrived at the Cape of Good Hope, bringing their Reformed Church and establishing trading posts for merchant and naval vessels and soon extending settlements into the arable lands to the north. There was continuing friction with the British, to whom the Cape Colony had been ceded by the Dutch in 1814 at the Congress of Vienna, and the Boers - 'farmers' in the Afrikaans language that evolved from early Dutch -- trekked north, eventually clashing with the British in 1842 at Port Natal, or Durban, and deflecting themselves westward. Later, in the nineteenth century, however, Boer pioneers founded the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (the latter perhaps better known as the Transvaal Republic). Boundaries were set following the brief Transvaal War, or First Boer War in 1881, which ended with the British defeat at Majuba and secured independence for the Transvaal, which the British had annexed in 1877. It was the Boers' good fortune - or perhaps misfortune in hindsight - when, in 1886, vast quantities of gold were discovered in the Transvaal in the area around and along 'the Reef', west and east of Johannesburg.

The discovery of gold caused an inrush of foreigners seeking fortunes or at least employment in the mines. The Afrikaners called them, generically, 'Uitlanders'. Many of them were British subjects and there were also quite a few Americans. The new arrivals agitated for a voice in local government and provoked a raid into the Transvaal along the West Rand on 29 December 1895 by a column comprised of armed volunteers, mostly recruited from the Bechuanaland Border Police and the Mashonaland Mounted Police by Leander Starr Jameson, colonial Administrator of Rhodesia (Chisholm, 1979, p16). The anticipated Uitlander uprising in Johannesburg never took place, however, and some 500 raiders were quickly suppressed by aroused burghers at Doornkop, with 21 fatal casualties and considerable international publicity. The troopers, along with their impetuous leader, were arrested, disarmed and locked up in Pretoria Town Jail. Eight rapid-fire guns and three light artillery pieces taken from them later appeared in Boer hands at Mafeking (Pakenham, 1979, p423).

The outbreak of war

President Kruger sent Jameson and the captured raiders to England for trial, where they were convicted of plotting against the Crown and sentenced to prison terms of fifteen months or more.

The British Government, frustrated by its inability to impose its imperial will on the burghers, once again confronted them. Negotiations failed, the Orange Free State joined forces with the Transvaal Republic. The British expanded their definition of the causus bellum (Justification for war) to include 'British paramountcy' in South Africa, without precisely defining the concept, but it was transparently a determination to reduce the status of independent republics to that of British colonies like the Cape Colony and Natal (Pakenham, 2002, p558).

The Anglo-Boer War began on 11 October 1899 and the Boers moved quickly to besiege the British at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. They were loosely organized into commandos, similar to militia in which each man joined up under an elected local leader, providing their own horses, arms and equipment and operating for the most part as mounted infantry. The Republics had obtained modern Mauser rifles from Germany, and these became the staple weapons of the commando, while some imported rapid-firing guns, and a few pieces of artillery were already in government arsenals.

A Boer commando was lightly armed and highly mobile and its members had been raised from boyhood to be excellent horsemen and expert marksmen. While they thwarted the British by pinning down isolated garrisons and harrying ponderous relief columns, their tactics were generally hit-and-run and they would disappear into the veldt before the British battalions could close with them (Knightley, 1976, pp77 -8). Worse for the British, their Army was widely dispersed throughout the Empire and sufficient was widely dispersed throughout the Empire and sufficient troops were not in place to cope with the conflict. It was necessary to draw regiments from distant colonial garrisons and to call upon Australia, Canada and New Zealand - for this was seen as a 'white man's war' - to provide reinforcements. An early strategic error was to deploy infantry battalions, until it became apparent that dealing with the mercurial commandos was a job better suited to cavalry and mounted infantry.

Foreign involvement

The commandos were augmented by foreigners joining them to fight either as individuals or formed into discrete units - Frenchmen, Germans, Scandinavians, Russians and Americans amongst them. Some of these foreigners were already resident in South Africa, particularly working in the goldfields; others arrived motivated by principle or simply by an urge to pursue adventure. There was a substantial American community of about 5 000, comprising mostly men resident in the Transvaal Republic as well as a number living and working in more remote areas where they could not be easily identified or counted. The community was divided between those who supported the British cause and those who sided with the Boers. Amongst the latter and those who subsequently came to South Africa to fight for the Boers, there was a sense that this was a class war between working people and capitalist overlords. According to Arthur Baynes, then Anglican Bishop of Natal, who visited prisoners of war at Pietermaritzburg, '[t]he Americans went so far as to say that the best government for the working man was the Transvaal Government' (quoted in Farwell, 1976, p93).

The British Government, personified by Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, trod very cautiously around the issue of Irish volunteers, fearing that a wave of perhaps 100 000 Irishmen and Irish-Americans might pour into South Africa and engulf a British Army already scarcely holding its own. Perhaps there was also a sense that such volunteers acquiring military training and experience could later use this to reinforce the Irish struggle for independence at home. This had certainly happened after the American Civil War, when many veterans had subsequently joined the Fenian Rebellion in 1867.

European governments followed these developmentswith intense interest and great empathy for the Boers, who were seen as valiant underdogs struggling for independence against a vast imperial power. The same concerns arose in the United States of America, but as she had recently embarked on her own imperial adventures in Cuba and the Philippines, her government abstained from openly supporting the Boer cause while suppressing the Filipino insurrection. Furthermore, Americans profited from huge shipments of horses and mules and their fodder, as well as preserved meat and other supplies, to the British (Farwell, 1976, p22). American newspapers tended to take sides with the Boers, and the noted journalist, Richard Harding Davis, was in the forefront of American correspondents who, if not pro-Boer, were at least anti-British in outlook.

John Hassell and the American Scouts

Among the Americans who not only took sides but also took up arms, one of the first was John A Hassell, a descendant of Dutch Huguenots who was living in Vryheid when hostilities began. He was a mining engineer by profession, and he had already won favourable attention from the Boers when he joined a group of Transvaal burghers to oppose the armed rebellion of the Uitlanders in 1896 (Farwell, 1976, p92). For this, he was made an honorary burgher. When war broke out in October 1899, Hassell was working in Zulu land; he immediately joined the Vryheid Commando in Natal, fought at the battles of Dundee and Talana Hill, took part in the Siege of Ladysmith where he was wounded at Caesar's Hill, and then was wounded again at Estcourt during the fighting along the Tugela (Thukela) River. He was present at Colenso when Winston Churchill was captured. His offer to form a new unit of Uitlanders was accepted and in Johannesburg he recruited some sixty volunteers for his American Scouts - a verkenningskorps.

John Shea, a grizzled veteran of the Spanish-American War, joined the Scouts as a lieutenant (Hillegas, 1900, p266). Others made up a total of about 86. Among them was the colourful 'Arizona Kid,' actually James Foster, whom Hassell described as 'a typical American cowboy ... frolicsome, lithe and reckless, always ready for any excitement, to take part in any sort of enterprise no matter what desperate chances were involved.' He had come to South Africa on a ship carrying mules, joined the British tranport to get to the front, and then deserted to the Boers (Farwell, 1976, p92). This was a route of entry for many Americans who ended up on one side or the other. A Texan called Alan Hiley, who, together with Hassell, wrote a history of the Scouts, claimed to have killed a fellow Texan, a Lieutenant Hollis (whom Howard Hillegas of the New York World refers to as Carron) of Lord Loch's Horse, in a skirmish along the Modder River, perhaps having singled out his target deliberately. This officer reportedly survived, although neither name appears in the War Office roster of Loch's Horse.

Hassell and his Scouts soon went south to fight Lord Roberts. The volunteers fought in numerous skirmishes and several battles through the Free State and north again to Pretoria, where Hassell sought the protection of the American Consul, anticipating that the war was coming to an end, rather than withdrawing with many others of his unit to Mozambique.

A rather sarcastic letter from Hassell, describing himself as 'Captain Boer Army', was published in the New York Times on 26 August 1901, in which he excoriated Arthur Lee, British Military Attache in Washington, for pronouncing the war over and the Boers defeated. In fact, the war was not over until the terms of surrender were signed in the Treaty of Vereeniging at Pretoria on 31 May 1902.

Colonel John Blake and the Irish Brigade

A great many of the volunteers on the Boer side were Irish and Irish-Americans, and one might suppose that they and the Boers had little in common. Roland Schikkerling, a young Boer serving with a commando, observed that while the German and Dutch volunteers were closer in blood, they seemed out of place in the Transvaal Army, while the Irish blended in so well that 'you could not pick Patrick out of a herd of the wildest Boers' (Schikkerling, 1964, p27).

In September 1899, an Irish Brigade was mustered into the Transvaal Army, largely composed of Irish and Irish-Americans 'recruited from the region's mines and commanded by self-styled Colonel John Y Fillmore Blake. Blake was an 1880 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and had risen to the rank of captain during previous active service experience as a US cavalry officer on the Plains during the Indian Wars (Farwell, 1976, p92). While opinions varied, a correspondent of The Times of London, embedded with the Boer Army, described the Brigade as comprising 'some of the worst sweepings of Johannesburg, led by an American adventurer called "Colonel" Blake. Their avowed object was loot, and that is probably all they would be good for' (Chisholm, 1979, p82).

The Brigade was augmented by the so-called Chicago Ambulance Corps raised among Irish-Americans by Finnna-Gael, who landed about 50-strong at Beira in Mozambique in April 1900 (Lee, 1985, pp53-4). The Portuguese authorities allowed them to entrain for the Transvaal, where they divested themselves of their medical guise, armed themselves and, under a Captain Patrick Q'Connor, fell in with the Irish Brigade, helping to swell its ranks. The ambulance service itself, including five doctors and two nurses, accompanied the corps and provided professional support for its volunteers as well as for Boer commandos in general.

The American correspondent, Richard Harding Davis mentioned in his book, With Both Armies, that he was coincidentally aboard the same train on his way to cover the war from the Boer viewpoint, as he had previously done while 'embedded' with the Crown forces.

The Irish Brigade or 'Wreckers' Corps' (Pakenham, 1979, p445) fought from Ladysmith to Pretoria in about 20 engagements, incurring eighteen dead and 70 wounded, including their commander. After Colonel Blake was wounded, Major John MacBride, an Irishman, took command and led the Brigade until December 1900, when they retreated into Mozambique with most of the Transvaal forces. Blake, apparently, fought on in the guerrilla war that dragged on into 1902, speaking Afrikaans and adopting the Afrikaner mould. (MacBride married the Irish nationalist, Maud Gonne, who had been an ardent supporter of the Boer cause, in Paris, in 1903 before returning to his native Ireland. He was subsequently captured by the British during the Easter Rising in Dublin and was executed in 1916).

Otto von Lossberg and the Boer guns at Sannah's Post

A German-born American called Otto von Lossberg volunteered his invaluable technical skills and leadership on the basis of his previous service as an officer in the Prussian 2nd Foot Guards in Germany. He was wounded several times and fought under General Piet de Wet, commanding the Boer guns at the Battle of Sannah's Post in the Orange Free State on 31 March 1900. Due in part to his effective direction of their artillery fire, the Boers captured hundreds of prisoners and seven guns and forced the British into a headlong retreat. President Steyn was quoted as saying to Davis, then serving as the correspondent for The Times who rode with Lossberg at Sand River, '[t]his is an American you should be proud of; we certainly are.' (Davis).

'Dynamite Dick' John King

Pennsylvanian John H King was a miner-turned-adventurer. Not to be confused with 'Dynamite Jack', Oliver Jack Hindon, a Scots volunteer, King was nicknamed 'Dynamite Dick' for his expertise in blowing up trains and bridges. King earned a reputation for bravery as well, when he and another man retrieved a seriously wounded comrade under heavy fire at the battle of Vaalkranz. The rescued Boer was Alec Brand, the son of Johannes Henricus Brand, a former President of the Orange Free State (Farwell, 1976, p92). King fought at Spion Kop in January 1900, where he captured an old friend who had joined the British side. According to a report by Howard Hillegas in the New York World, King and his compatriot had a brief conversation, shook hands, and then King shot his unnamed friend to death. There are other anecdotes from participants claiming that Americans on each side took pains to identify and target their fellow countrymen.

American pro-British volunteers

All in all, there may have been as many as 300 Americans in the Boer forces during the war, while some estimates of American participants on the British side run into several thousand. Winston Churchill covered the war as a correspondent and he noted that many Americans and other foreigners were in the ranks of the Imperial Light Horse, a cavalry unit raised in Johannesburg in September 1899 to serve with the British Army during the war that broke out the following month. (This famous unit is perpetuated in the Light Horse Regiment, a citizens' component of the South African National Defence Force today).

Arthur Conan Doyle was also in South Africa at the time, subsequently writing a definitive history of the war. He reported that an entire squadron of Roberts' Horse was composed of 'Texas cowboys'. Many of them came to South Africa tending the thousands of horses and mules shipped from America for the British Army and stayed on to soldier in colonial regiments. Roberts' Horse was formed in January 1900 as one of many colonial volunteer units raised particularly for the war. Trooper Leonard Chadwick was elected by his comrades as the most distinguished soldier in a South African colonial unit and was accordingly awarded one of the commemorative scarves knitted by Queen Victoria (Black and White Budget, Vol II, p750). It must have come as some surprise that the most outstanding South African soldier was an American! Chadwick, however, had already won the Congressional Medal of Honor while serving in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War. He received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his bravery at Paardeberg (London Gazette, 16 June 1902) and received a Mention in Despatches by Lord Roberts on 2 April 1901.

Another veteran of the US Navy and the Spanish-American War who served with the British colonial forces was William Thompson who, with two un-named colleagues, attempted to make off with a piece of the besiegers' heavy artillery while it was in action at Ladysmith. They were all taken prisoner by the Boers (Hillegas, 1900, p267).

Two American railway engineers, Louis Irving Seymour and Joseph Clement, were commissioned into the Railway Pioneer Regiment raised in Cape Town under British auspices in October 1899, after Seymour had immigrated to the Cape Colony from the Transvaal. Major Seymour and his friend, Lieutenant Clement, were both killed on 14 June 1900 while defending a railway bridge they were constructing across the Sand River in the Orange Free State. According to Byron Farwell, Seymour was evidently killed by an American sharpshooter serving with Hassell's American Scouts.

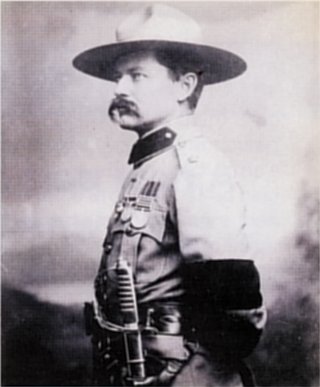

Undoubtedly the most notable among Americans who earned reputations fighting for the British was General Roberts' Chief of Scouts, Major Frederick Russell Burnham. Lord Roberts, Theodore Roosevelt, Richard Harding Davis and the author Rider Haggard were all among his admirers. Burnham had fought in the Indian Wars in the American Southwest, scouted in Rhodesia during the Matabele Rebellion of 1896 and was prospecting for gold in Alaska when he was called to serve on Roberts' staff. In the Transvaal, he experienced a number of adventures that read like poor fiction, but are well documented. Much of his time was spent behind Boer lines; twice captured, he twice escaped. While collecting intelligence for Lord Roberts, he also blew up railway lines, including the Boer's vital supply route between Pretoria and Lourengo Marques. He was seriously wounded during this last exploit. Invalided to England in July 1900, he was invited to dine with the Queen. King Edward VII subsequently awarded Burnham the Distinguished Service Order for his heroism (Farwell, 1976, p95).

Bibliography

Black and White Budget Volume II (W J P Monckton, London).

Blake, John Y Fillmore, A West Pointer with the Boers: A Personal Narrative of Colonel J Y F Blake, Commander of the Irish Brigade (Angel Guardian Press, 1903, reprint Kessenger Publishing Co LLC, Whitefish, MT, 2007).

Burnham, Major Frederick R, Scouting on Two Continents (Doubleday Page & Company, New York, 1926).

Chisholm, Ruari, Ladysmith (Jonathan Ball, Braamfontein, South Africa, 1979).

Davis, Richard Harding, With Both Armies (Scribners Sons, New York, 1900).

Farwell, Byron, 'Taking Sides in the Boer War' in American Heritage, Volume 3, April 1976.

Giese, Toby, Saga of John Fillmore Blake: The Last Missouri Rogue (self-published, Kansas City, 1994).

Hassell, John, A, 'A Boer Captain's Opinions' in The New York Times, 26 August 1901.

Hiley, Alan, R H and J A Hassell, The Mobile Boer (Grafton Press, New York, 1902).

Hillegas, Howard C, With the Boer Forces (Methuen, London, 1900).

Knightley, P, The First Casualty (Harcourt Bruce Jovanovich, New York, 1976)

Lee, Emanuel, To the Bitter End: A Photographic History of the Boer War, 1899-1902 (Butler & Tanner, Frome and London, 1985).

McCracken, Donal P, MacBride's Brigade: Irish Commandos in the Anglo-Boer War (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1999).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War (Random House, New York, 1979).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Scramble for Africa (Abacus, London, 2002).

Ruda, Richard, 'The Irish Transvaal Brigade' in Irish Diaspora Studies, Volume XI, Number 45, Winter 1974.

Schikkerling, Roland William, Commando Courageous (Hugh Keartland [Publishers] pty Ltd, Johannesburg, 1964).

Winks, Robin W (ed), British Imperialism (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1967).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org