The South African

The South African

About the author

Robin Smith is a military history researcher of Anglo-Boer War sites. He lives in Hilton, KwaZulu-Natal.

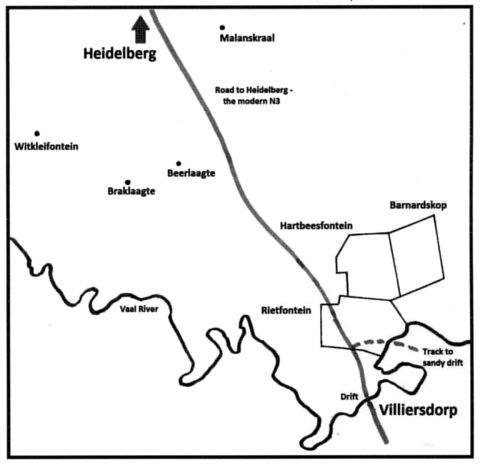

Executions by the military during times of war might not be considered very remarkable. Spies, deserters and traitors can expect small mercy from their own side. Nevertheless, the case of two young Boers, Pieter Barendse Bouwer and Adolf Jacobus van Emmenes, members of the Heidelberg Volunteers, executed on the farm Rietfontein on 24 August 1901, is particularly tragic.

'Joiners' were Boers who had 'joined' their enemy, the British, and fought against their own people. 'Hendsoppers' were Boers who had refused to fight further when the guerrilla campaign began after the British occupation of, firstly Bloemfontein and then Pretoria, in the first half of 1900. Both were despised as 'verraaiers' - traitors to the cause of the Boer struggle for independence.

Pieter Bouwer Pieter Bouwer was a school teacher in Heidelberg, a small town south-east of Johannesburg, which had a majority of Boer inhabitants but also a significant English-speaking community. His position would have provided him with a better living than the hard struggle for existence on a small farm. His parents farmed in the Klip River district of Heidelberg and were still living at the time of his death. There is little more known about them. After the war, when Bouwer's widow was in some difficulty, they no longer seemed to be around to support her, so they do not seem to have survived the War. During 1901, Bouwer had joined the Heidelberg Volunteers and was listed as a private.

Adolf van Emmenes

Adolf (Dolf) van Emmenes was born on the farm 'Witpoort' near Heidelberg. (No farm by that title is shown either on modern survey maps or contemporary maps of the area, so perhaps the family did not own the land that they occupied). As a youth, he was recommended for training with the Staatsartillerie van de Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, the only regular military unit in the Transvaal (or the ZAR as it had become known). Heidelberg Commandant, Fanie Buys, made the recommendation to the authorities. Dolf served almost a year and was said to have worn his uniform with great pride. At the outbreak of war, his father and several of his brothers were on commando. Sometime in the second half of 1900, they voluntarily surrendered on their farm to a British column. They all then signed the oath of neutrality and may have moved away from the farm to live in Heidelberg. Dolf van Emmenes remained at 'Witpoort' until November 1900. The farm was constantly raided by the fighting Boers. He then fled to the British camp at Greylingstad and sought sanctuary there (Blake, 2010, p79).

The van Emmenes farm was never able to provide more than bare subsistence for the family and so their decision to move into Heidelberg may have been dictated by financial considerations. It is known that at least two of the van Emmenes brothers, and probably their father and the others, became members of the Heidelberg Volunteers. This was a volunteer burgher corps organised by the British Heidelberg Commissioner, Major John Vallentin, comprised mostly of English-speaking inhabitants of the town and a few Afrikaners, who were thus considered 'joiners' (Uys, 1981, pp 153-5, has much detail of Vallentin and his volunteer force. Vallentin was killed at Onverwacht, also known as Bankkop, in a skirmish with the commandos of Opperman and Brits on 4 January 1902.) For more information, see Robin Smith, 'The battle of Onverwacht, 4 January 1902' in Military History Journal Volume 13 No 2, December 2004). Vallentin's Heidelberg Volunteers were known derisively by the Boers as the 'Witkop Commando' ('the White Head Commando', a reference to the white hat bands that they wore).

Prelude to the tragedy

Mr J G van den Heever's memoirs of the Anglo-Boer War, first published in 1941, have much detail of events in the Heidelberg district at this time. While the British were in control of the towns and had blockhouses and wire entanglements along the railway lines, they could only venture into the countryside in daylight with a strong, heavily-armed force. The tactics that they employed were to raid the farms in the area after sundown with scouts provided by the Heidelberg Volunteers and local black people. Any unwary Boers would be captured and livestock could be driven back into town or to the nearest railway line before light.

One night in July 1901, a farmer, P du Preez, of the farm 'Witkleifontein', was killed during a night raid on his farm. Some of the Heidelberg 'joiners' were apparently responsible for what seems to have been the cold-blooded murder of a decrepit old man who was unable to go on commando (Van den Heever, 2001, p89). The fighting Boers felt that this crime should not go unpunished and that they should not be expected to show mercy to any 'joiners' whom they might capture (Blake, 2010, p74, quoting van den Heever's memoirs. There is no independent confirmation elsewhere of this incident). Van den Heever's memoirs were published forty years after the event and must thus be treated with some caution. At that time, in the winter of 1901, the countryside was being cleared, the inhabitants relocated and the livestock either utilised by the British or slaughtered out-of-hand.

The women's laager

In order to evade British columns, Boer women organised laagers and tried to hide in places where they thought they would not be found. In July 1901 the women of the Heidelberg district assembled such a collection of wagons. This tactic was seldom very successful, although this particular laager may have been something of an exception. The location of the laagers was often given to the British by the local black inhabitants and that was probably the source of Vallentin's intelligence on 24 July. He left Heidelberg some hours before dawn at the head of a strong column, heading for Beerlaagte, the reported site of the women's laager. He may not, however, have had intelligence of a Boer force encamped the previous night at Malanskraal, which was closer to Heidelberg. If he did know about them, clearly he did not consider them to be any kind of threat to his raid. The British force was comprised of regular mounted infantry and a number of Heidelberg Volunteers, including some of the Heidelberg Afrikaners (Uys, 1981, p160).

Scouts serving with the Boer commandos warned the women to move further south and they camped near the Vaal River at Grobbelaarsdrift, now under the waters of the Vaal Dam. The Boers under Field Cornets Georg (Org) Meyer and Hendrik Kamffer intercepted and ambushed the British at the farm 'Braklaagte', causing them to retire to Heidelberg. The Boer accounts of the engagement at 'Braklaagte' describe a rout of the British force. Nevertheless, Major Vallentin and Scout Gorman covered the retirement back to Heidelberg, rescuing four of their men, who had been dismounted. Both men were Mentioned in Despatches (an honour just short of the award of a medal) (Uys, 1981, p161). Another account (Ankiewicz, 2009, p81) says that the battle took place in misty weather and that the 'joiners' panicked at the prospect of capture by the Boers and many fled in all directions into the thick mist.

In the course of the engagement, four of the Heidelberg Volunteers were killed. One of them was Eddie Morrison, best friend, before the war, of Louis Slabbert, one of the commando members. Three more of their pre-war friends lay dead too - John Beck, Frederick Nel and Philippus van Eeden (Ankiewicz, 2009, p81, also mentions another, a man by the name of Archie Anderson). Three prisoners were taken: Pieter Bouwer, Dolf van Emmenes and a man described as 'one Scheepers' (Uys, 1981, p161). Scheepers was wounded, seriously, according to Field Cornet Hendrik Kamffer. Kamffer and Assistant Field Cornet Andrew Brink had chased Scheepers, who may have been G C Scheepers of the ward Kliprivier, who was known to have deserted the Boers (see Blake, 2010, Note 13, p287), and Brink shot and wounded him. While he lay under guard on the ground, according to Kamffer, a lone rider appeared. He was recognised as Danie Maartens, who was very excited and asked if the commandos had captured his brother-in-law, Scheepers. When told that he was lying wounded under guard a short distance away, Maartens rode up to him, dismounted from his horse and shot him between the eyes.

According to Maartens, Scheepers and certain other joiners had, some nights previously, raided Maartens' farm, then occupied only by his wife and small daughter. Mrs Maartens was a sister of Scheepers, and she and her little girl were driven into the veld about 1 000 yards (914 metres) away from the farmhouse, which was then set alight. Barefoot and clad only in their nightclothes in the bitter July winter weather, they were near to death from exposure when Danie Maartens found them the next morning. His emotions can well be understood, but there is no confirmation elsewhere of this incident (see Blake, 2010, p15, quoting Hendrik Kamffer, Herinneringe).

Another 'joiner' was able to evade the commandos and make his way southwards. His name was Piet Jordaan and he had the misfortune to run into the women's laager at Grobbelaarsdrift. He denied that he was a 'joiner', but was nevertheless made to run the gauntlet. They lashed him with sjambokke (rawhide whips) and he sought refuge in the water of the Vaal River, which was icy cold at that time of year (Uys, 1981, p161; Blake, 2010, p75).

A number of the prisoners were released, but Bouwer and van Emmenes, who were known personally to many of the Boers, were taken with the commando as they moved away from the scene of the engagement, back to one of the numerous places in the area where they could remain undiscovered by their enemy. Unlike Jordaan, who had been soundly beaten by the womenfolk, they were probably not physically abused. Blake (2010, p56) quotes Kamffer who says, in Afrikaans, that they were 'goed karnuffel, which in English is translated as 'roughly manhandled'. However, Kamffer repeatedly taunted Bouwer by indicating the sun and saying: 'Look carefully, young man, tomorrow you might not see it again!'

The court-martial

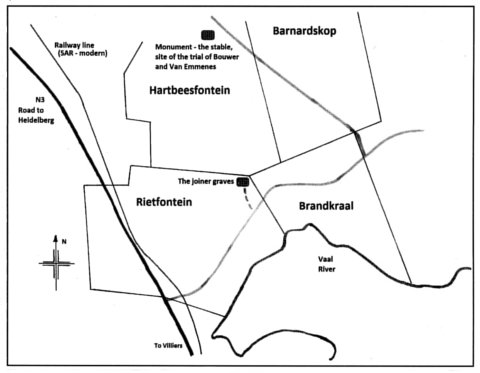

A court-martial was assembled under the command of Commandant Fanie Buys. The two accused were tried in a stable on the farm 'Hartbeesfontein' in a hearing that took two days. The record of the proceedings of the court has been lost and so it is not known with what exactly they were charged. Van den Heever says that murder (of du Preez, perhaps?) was one of the charges, but that certainly they must have been accused and found guilty of high treason. Many questions about the trial will remain unanswered. Were the two accused required to conduct their own defence? Even this is unknown in the absence of any record (Blake, 2010, p77).

In his memoirs, van den Heever, in a passage that may have been influenced and indeed written by his relative, the well-known Afrikaans author, C M van den Heever, described the reaction of the two accused when the death sentence was pronounced: They turned deathly pale and had difficulty holding themselves erect as they were led away. The rest of the passage is an impassioned attempt to justify the imposition of the sentence of death that was given to the two young men: 'Wreed maar ook beslis en regverdig ... ' ('Cruel but also certain and justifiable'). Clearly this paragraph of the 'Memoirs' was written by a man of letters (Blake, 2010, p77, quoting van den Heever in full).

About half an hour after the court concluded, van den Heever and another man, H Bronkhorst, were told to leave that night for the eastern Transvaal (Uys, 1981, p164, quoting van den Heever's memoirs, p81; the second man was, according to Blake, 2010, p77, H Badenhorst, while Ankiewicz, 2009, p83, names him Hendrik Boshoff). They were to locate the itinerant Transvaal government, who were evading discovery and capture by the British columns scouring the countryside. Somewhere near the Swaziland border, they found F W Reitz, the State Secretary. The sentence was confirmed, according to a British report, by General Louis Botha himself and van den Heever and Badenhorst made their way back to their commando.

Presumably these two took with them a written account of the findings, if not a summary of the proceedings of the court over the two days of the trial. No such documents have survived, nor has the document allegedly signed by Botha, authorising the death sentence. The journey there and back took fifteen days, such were their difficulties in evading capture and penetrating the wire barriers between the lines of blockhouses that were by then extended over the country. Van den Heever's account of his journey to find the Transvaal government describes several meetings with Boer farmers, but they apparently did not encounter any British patrols or columns.

The condemned men

While awaiting the return of these emissaries, Bouwer and van Emmenes were held in the jail at Villiersdorp (Villiers today, where the prison still exists as part of the local South African Police Service Station, although considerably altered). Their jailer was Frans Kruger and there was also a young telegraphist present, J A C Kriek. Kruger asked Kriek to give the prisoners the opportunity to escape; this to be done when Kruger was getting water for his wife's cooking. Kriek was to indicate an escape route to them, but apparently the prisoners refused this offer. They suspected a trap and feared they might be shot in a prepared ambush and so preferred to stay where they were. Other assertions by Kriek, reported by Uys, were that they were resigned to their fate, whatever it might have been. (It is not known whether Kruger received instructions from a senior Boer officer to allow the prisoners to escape from custody. Kriek, in his old age, was interviewed by Ian Uys. Ludwig Ankiewicz, a local farmer, remembers meeting with Kriek, then a very old man, around the same time).

The Execution

Immediately after the return of van den Heever and his colleague, a message was given to the prisoners that the death sentence had been confirmed and that they would be executed within 24 hours. On 24 August 1901, the prisoners were taken by horse cart to the farm 'Rietfontein', north of the Vaal River and a short distance from the stables where the court-martial had sat to try the two men. A Dutch missionary, Mr Poelakker, who had visited the men regularly while they were imprisoned, accompanied them on their last journey. The location of the grave is at S26°56' E28°37' and ruins of the stable at S26°53' E28°36'.

At this point, the various accounts of the execution become somewhat difficult to reconcile with what might actually have happened. According to both Kamffer and Louis Slabbert (whose accounts appear in an article by H J Jooste entitled 'Veld Cornet (Field Cornet) Salmon van As' in Christiaan de Wet Annale, Number 6, October 1984), the condemned men were required to dig their own graves, and were then shot and immediately buried. It is not clear whether either Kamffer or Slabbert were actually present at the execution. However, both Kriek and van den Heever claim that the graves had been prepared the previous evening and that, furthermore, the two men were blindfolded so that they should not see the open graves. They were led to the head of their graves, where they were required to stand. Once again, it cannot be ascertained that Kriek and van den Heever were eye-witnesses, but their version seems the more plausible.

While they stood blindfolded next to their graves, Dominee Poelakker comforted them with a reading ker comforted them with a reading ker comforted them with a reading of some verses from the Bible. He of some verses from the Bible. He told them of the life hereafter, which they would enjoy 'thanks to the mercy of Christ'. He is said to have asked them to convey greetings to his ead parents and to tell them that he would soon be joining them. Finally, he shook hands with each of them. (Blake, 2010, p80; Uys, 1981, p165). The firing squad of twelve men was assembled, six for each of the prisoners. As usual on these occasions, six rifles were loaded with blank cartridges and six with live rounds. The members of the firing squad were required to choose one of the guns. They would not know whether they had picked up a rifle loaded with a blank or a live round. The signal to fire was given by an officer hitting a stone against a shovel. It was half past nine in the morning.

For the young men of the firing squad, this must have been extremely traumatic. Bouwer and van Emmenes were personally known to a number of them and some members of the firing squad had been Bouwer's pupils in the school at Heidelberg. Van den Heever said that some of the members of the firing squad were close relatives of the two victims. The psychological effect of this on these young men must have been severe and longlasting.

It was later said that one of the men, apparently van Emmenes, was not killed instantly. The Boer doctor, a German by the name of Otto Schnitter, was present and required to certify that the prisoners were both dead. It was said that he climbed down into the grave and opened the jugular vein. More normal procedure would have been to check the pulse which would tell whether the heart was still beating. Alternatively, it is relatively simple to establish whether the man was still breathing.

The above story emanated from a number of English-speaking members of the Heidelberg Volunteers who had been captured during the fight at Braklaagte and subsequently released. Among them was Sergeant-Major Schroeder, who reported the capture of Bouwer and van Emmenes by the Boers (Blake, 2010, p78). Bouwer and van Emmenes were enlisted as privates in the Heidelberg Volunteers and were officially reported as 'missing-captured'. This required that an enquiry be instituted into the circumstances of their capture and subsequent execution. Assistant Field Cornet Andries Jacobus Greyling of the Heidelberg Commando was later captured and reported to the British on 3 May 1902 that he had been an eye witness to the execution. It was Greyling who first mentioned the story of the opening of the jugular artery. (Grundlingh, 2006, p294, reports the same information in a factual manner).

The Enquiry

At the subsequent enquiry, a Sergeant Fowlds of the 2nd National Scouts made the declaration under oath that he had 'heard it said that the opening of the artery was for the purpose of allowing van Emmenes to bleed to death' (Blake, 2010, p81). Although neither his nor Greyling's reports could be substantiated factually, the story has been repeated in the district for many years, even up to the present day. This is according to Ludwig Ankiewicz, who grew up on the farm 'Barnardskop' and who is an undoubted authority on the history of the district, and corroborated by a number of other residents of the area. Evidence presented to Lieutenant Nixon, who was responsible for the investigations leading to the establishment of an enquiry, concluded that van Emmenes was hit by five bullets but was not killed instantly. Does this indicate that Bouwer, in turn, was killed instantly by a single shot? The British enquiry did not recommend that anyone be prosecuted in view of the lack of any conclusive evidence.

Van den Heever provides a detailed description of the whole affair, but at no time mentions anyone by name. At the time that he wrote his memoirs, he was living on the farm 'Beerlaagte', near to where the joiners had been captured. His intention was clearly to spare surviving relatives of the two men any further pain, but the context of his account shows that it is unquestionably about Bouwer and van Emmenes (Blake, 2010, p82).

Bouwer's young wife was almost immediately in difficulties. The couple had a daughter, who was seventeen months old at the time of her father's execution, and a son born on 31 July 1901, while he was in prison at Villiers. Less than six weeks after the death of her husband, Nicolina Bouwer lost her little daughter, followed only three months later by the death of her baby son.

The British authorities were sympathetic and she was granted £80 as compensation for war damages as her husband's estate was worthless. Similarly, van Emmenes's father claimed and was awarded compensation, the British authorities noting that he was 'in poor circumstances'.

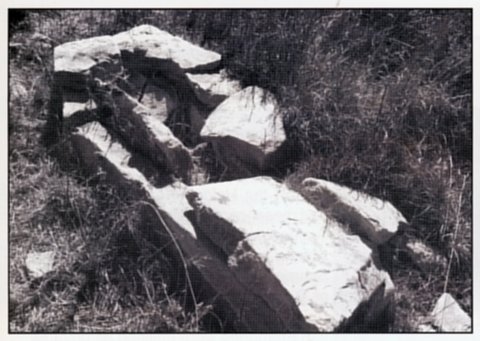

The site of the graves might have been lost were it not for the suicide of Koot Bierman (21), who shot himself on the farm 'Hartbeesfontein'. It seems that he had managed to get into serious financial difficulties. Owing to his suicide, his family would not allow him to be buried in the family plot on their farm. He was interred next to 'the other two murderers' and stones were arranged over the grave roughly in the shape of a coffin. Because of this, the location of the grave has not been lost; it is on the boundary line of the farms 'Rietfontein' and 'Hartbeesfontein' .

The memorials

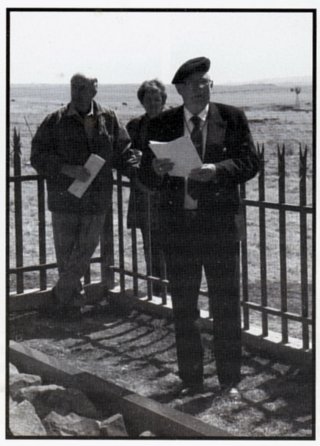

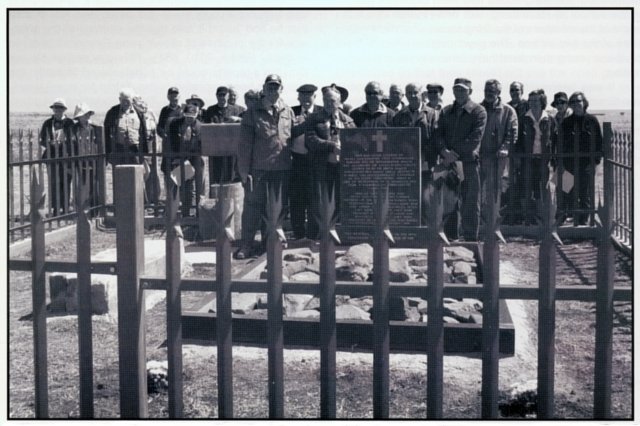

Bierman's grave and its coffin-shaped stone surround were still intact in 2010, although the stones had been somewhat disturbed. The last resting place of Bouwer and van Emmenes was an overgrown mound of earth. During 2010 members of the South African Military History Society, led by committee member David Scholtz, decided that it would be appropriate to erect granite memorials over the grave and at the site where the court-martial took place. While the conduct of Bouwer and van Emmenes in taking up arms against their own countrymen cannot be condoned, the members of the Society felt that the history of this whole affair and their burial place should not be allowed to disappear into obscurity.

Ludwig Ankiewicz, a local farmer and an undoubted authority on the history of the district, and other residents were very supportive of the project. It was agreed that there would be English and Afrikaans inscriptions for the memorials at 'Rietfontein' and 'Hartbeesfontein' to read as follows:

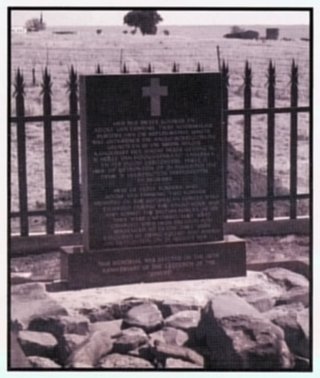

'Here lie Pieter Bouwer and Adolf van Emmenes, two former members of the Republican forces who deserted during the Anglo-Boer War and joined the British forces. After they were captured, they were charged with high treason and sentenced to death. They were executed by firing squad and buried on Rietfontein on 24 August 1901.'

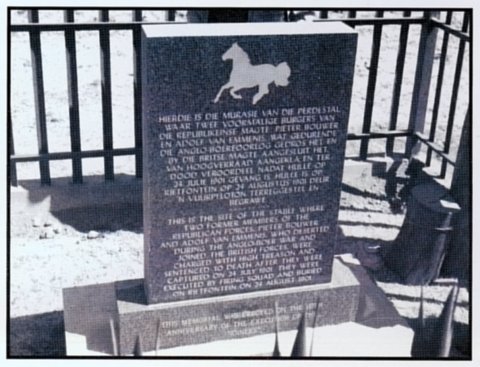

'This is the site of the stable where two former members of the Republican forces, Pieter Bouwer and Adolf van Emmenes, who deserted during the Anglo-Boer War and joined the British forces, were charged with high treason and sentenced to death after they were captured on 24 July 1901. They were executed by firing squad and buried on Rietfontein on 24 August 1901. '

A stonemason was engaged and the granite memorials over the grave and at the stable site were erected on 25 July 2011. The joiners' grave, once the overgrowth had been removed, was found to be a soil mound covered with rocks. These must have been collected from the vicinity and placed there, possibly by members of the men's families, to prevent wild animals from digging up the remains. It was thought best to flatten the mound and lay a granite border around the grave. The rocks were replaced over the grave within the granite border and the memorial was erected at the head of the grave. At the stable site, the ground was flat and the job easier. A foundation was laid and the memorial was erected to face the road passing by the remains of the stable.

On 26 August 2011 the memorials to these two tragic figures were dedicated in a ceremony attended by a number of interested people. Ludwig Ankiewicz, in a short speech, described how these two young men came to be executed by their own people. Nigel Mason, an Anglican lay minister, delivered a short burial service, something Pieter Bouwer and Adolf van Emmenes had not been given on the day they died and were interred. The ceremony took place two days after the 110th anniversary of their deaths and was testimony to the fact that the passing of time has caused much of the bitterness towards the 'joiners' to dissipate. Whatever their reason for taking up arms against their own people, may they now rest in peace, perhaps knowing that their story will not be forgotten.

Acknowledgements

The writer must acknowledge that this article has drawn heavily on the chapters in Ian Uys's and Albert Blake's books dealing with this sad event. Ludwig Ankiewicz's booklet on events in the area of the Suikerbosrand has been equally informative.

Ian Uys's account, Heidelbergers of the Boer War, written in 1981, tells the story of Bouwer and van Emmenes. Much of it is based on an interview that he had with J A C Kriek, as related above. Kriek had been a teenager at the time of the Anglo-Boer War and was a very old man when Uys learned that he was still alive and living in Heidelberg in 1974. More recent research has been undertaken by Albert Blake for his book, Verraaiers, which devotes a chapter to the two young men.

Bibliography

Ankiewicz, Ludwig, Vanaf die Suikerbosrant tot by die Vaal rivier: Die deel van die Ommidraai Kronkelroete. (self-published by the author, 2009).

Blake, Albert, Boereverraiier: Teregstellings tydens die Anglo Boere oorlog (Tafelberg, CapeTown, 2010).

Christiaan de Wet Annale, Number6,Octobe(1984.

Grundlingh, Albert, The Dynamics of Treason: Boer collaboration in theSouth AfricanWar of 1899-1902 (Protea Book House,Pretoria2006, translation from Afrikaans by Dr Bridget Theron of Grundlingh, A, Die 'Hendsoppers'en 'Joiners': Die rasionaal en verskynsel van verraad [Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria, 1979]).

Kamffer, Hendrik, Herinneringe(translation into English as Memoirs) in the Ian Uys Collection in thearchives in Pretoria.

Uys, Ian, Heidelbergers of the Boer War (Ian S Uys, Heidelberg, 1981).

Van den Heever, J G, Op Kommando onder Kommandant Buys (1941, reprint by Bienedell Uitgewers, Pretoria, 2001 ).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org