The South African

The South African

This incident occurred when I was serving with the 2nd Army, quartered on the Ypres Salient, in October 1918, just one month before the Armistice was signed. My regiment - the 26th Battalion Royal Fusiliers in the 124th Brigade of the 41st Division, which latter was commanded by the late General Sir S Lawford (incidentally also Royal Fusiliers) - was holding part of the line during the winter of 1918, operating in front of Comines.

Zero Hour, as it was known then ['H' Hour in the Second World War], was at 06.00 hours and our attack, which took place on a very foggy morning, was met by a stiff German counter-barrage of shell-fire, together with mortar and machine-gun fire. I was in charge of 'D' Company and, after some fifteen minutes or so of pure HELL, I found myself left with one subaltern, Second Lieutenant Layfield, and six other ranks; the rest of the company either having been killed, wounded or hidden by fog. Suddenly, a burning German Regimental Aid Post loomed out of the fog, having been set alight by our creeping barrage of artillery fire. Another 400 yards (365 metres) or so further along and our little party was confronted by a German battery position, which had previously been annihilated by our shell-fire. This position was in an utter shambles, with dead and wounded men and horses and overturned limbers lying everywhere. (In the First World War, field guns were mainly horse-drawn, not self-propelled).

At this stage, the fog was beginning to lift. As I was standing next to an artillery limber which appeared to be undamaged, several bullets whined over my head all too closely - and, at the same time, I observed that a single enemy gun was positioned about 400 to 500 yards ahead (365 to 460 metres), on the other side of a ploughed field. Supposedly this was the one and only gun which had managed to get away from the battery positions mentioned. The barrel must have been very hot, due to its incessant firing, as the shells were turning and twisting in the air and landing some distance from us without even exploding (a sure sign of overheating) I considered that the rifle fire came from snipers covering the fire of this lone artillery piece. There and then I decided to capture the gun with my small party.

There was a slit trench close at hand, about twelve feet (3,6 metres) long, and I ordered my party to jump into this for cover whilst I devised a plan of campaign. As I began my own jump into the trench, there was a sudden flash in front of my eyes and a distant sound like the crack of a horsewhip, but nothing seemed to be amiss. In a matter of a few minutes, I had my plan - to split my small force into two, Lieutenant Layfield with three other ranks to engage the gun position from the right side of the plough, and I and three other ranks to engage the gun position at the same time from the left flank. The plan worked admirably. As both parties converged on the gun position simultaneously, the German gunners surrendered and I chalked up '26th Battalion Royal Fusiliers' on the gun.

Shortly afterwards, personnel of various units began to arrive out of the blue, as the fog lifted completely and the enemy had withdrawn to alternative positions. We had launched a very successful offensive, and had advanced a good distance that day. We consolidated our new positions and the next morning our 41st Division was relieved by the 9th Highland Division. Our division proceeded to Divisional Rest for a period.

As is customary in the Service, when columns are on the march, a halt is called for ten minutes' rest at ten minutes to the hour, every hour, and units 'fallout' on the left of the road. During one of these halts, I decided to inspect my box-respirator, which I had been wearing in the 'alert' position during the attack the day before. (The 'alert' position ensures that the respirator, in its satchel, is tied in position across the chest, approximately at heart height, for quick adjustment if required in case of a gas attack). I unbuckled the flap and turned the respirator, still in its satchel, upside down. To my astonishment, the charcoal contents of the respirator began to trickle to the ground, forming a small pile. On further investigation, I observed that a bullet had passed clean through my respirator, in line with my heart. Either the German sniper had just failed to register a heart shot, or I had turned my body at the crucial moment when I had jumped into the trench. Surely not many people can claim such a close escape from death - this was a direct hit on the respirator, in the region of the heart, without a scratch to me, which obviously explains the flash and sound like the crack of a horse-whip described earlier.

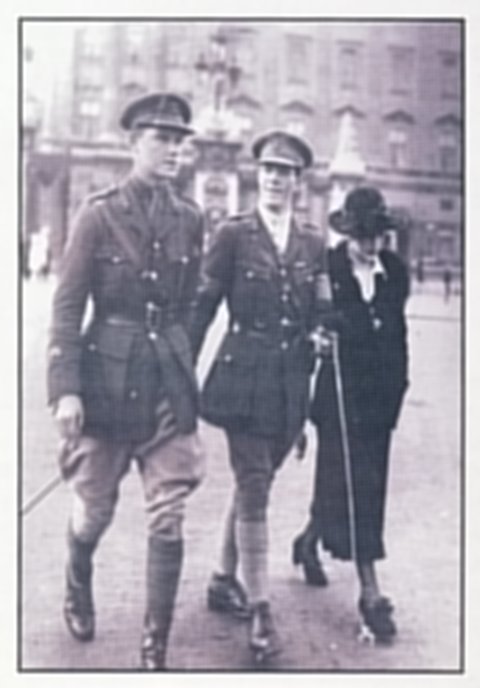

Lt W V Willson after receiving the MC

The Military Cross and First and Second World War medals of Capt W V Willson MC

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org