The South African

The South African

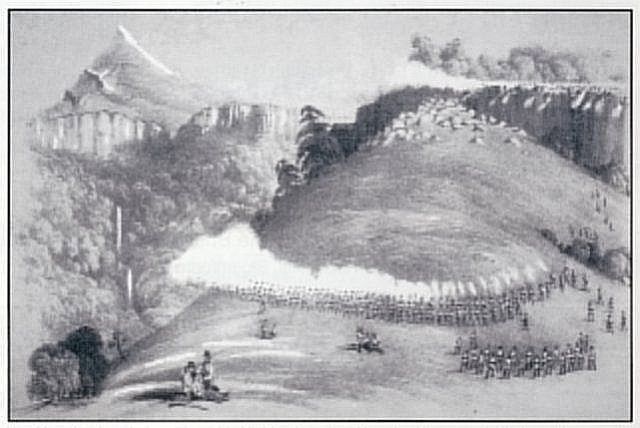

Attacking the Amatholes. The 74th Highlanders attacking the Xhosa and Khoi positions on the Zingcuka ridge from the Amathole basin on 26 June 1851.

The Xhosa and Khoi occupied the ridge where the Zingcuka (Wolf Ridge) Forest Station is now located.

The Hogsback peak is on the left. (Source: W R King, Campaigning in Kaffirland [Saunders & Oxley, London, 1853J).

Introduction

The battle described in these pages took place in the early stages of the War of Mlanjeni, in mid-1851. The scene of the fighting remains one of the little-known battle sites of the frontier wars or wars of dispossession in the Eastern Cape. Whilst the 1850-53 war has enjoyed considerable attention from historians, the first major offensive undertaken by the British and colonial forces in 1851 has generally been overlooked. Standard popular accounts such as those of J Milton and N Mostert, for example, make no mention of the battle. D Y Saks has drawn attention to another lesser known battle in the War of Mlanjeni - in the Fish River bush - which was depicted by Thomas Baines. Fortunately for posterity, the British column was accompanied by the artist Thomas Baines. He left a valuable pictorial and written record which, taken together with the written accounts by some of the participants and the official dispatches, enable us to reconstruct the events and to follow in the footsteps of the soldiers who took part in the battle for the Amatholes.

The outbreak of the War of Mlanjeni on 24 December 1850 was the culmination of a long list of frustrations and tensions on the Cape's eastern frontier. Chief amongst the causes was Xhosa resentment at the loss of territory with the establishment of the Crown Colony of British Kaffraria between the Kei and Keiskamma rivers after the War of the Axe in 1846-7 and the attack by Sir Harry Smith, the Governor of the Cape Colony and Lieutenant Governor of British Kaffraria, on Xhosa traditional institutions like chieftainship, traditional marriage customs and other aspects of Xhosa culture at the heart of their society and independence. The prophecies of the young diviner, Mlanjeni, occurred in this context. Friction between the Ngqika and military settlers at Woburn, Auckland, Ely and Juanasburg, Smith's tactless deposition of Chief Sandile and his subsequent outlawing provided more immediate causes of the conflict (D A Webb, 1998, p 45). Indeed, given the conditions on the frontier in 1850, the three years of peace after the War of the Axe can be seen as an interlude during which the Xhosa regrouped and built up their resources for another attempt to throw off the British yoke.

Hostilities recommenced when the Nqgika successfully ambushed a British column which had been sent out by Smith in an attempt to intimidate the Ngqika, in the Boma Pass on Christmas Eve 1850. The hated military villages in the Tyhume valley were attacked the next day. Smith was besieged at Fort Cox. Fort White, Fort Hare and, later, Fort Beaufort were attacked. The conflict broadened when the subjects of the Ndlambe chief, Siyolo, and Maphasa's Thembu entered the war. It escalated further when the so-called 'Kaffir [sic] Police' (Smith's indigenous police force in British Kaffraria) and large numbers of the Khoi Cape Mounted Riflemen crossed over to the Xhosa. It took on yet another dimension when the Kat River Khoi and the inhabitants of Shiloh mission also took up arms against the British. Significantly, Chief Phato of the Gqunukhwebe remained loyal to the British and the British forces were able to utilize the Buffalo line wagon route for supplies from their landing place at East London. Smith, whose cheerfully optimistic accounts of the progress of the war were continually contradicted by events, was recalled as Governor in 1852. His successor, Sir George Cathcart, was only able to proclaim peace in March 1853. After the initial flush of successes against the British, the Xhosa and Khoi launched long-range raids into the Colony, burning homesteads and capturing cattle and other livestock. Notwithstanding these incursions into the Colony, and despite heavy fighting around Whittlesea, Shiloh and British incursions into the Transkei, the war primarily centred on the Amathole mountains, the Waterkloof and Kroomie heights, and the Fish River bush (Webb, 1998, p 45). The war, which dragged on for nearly three years, was waged with conspicuous brutality, especially by irregular units like Lakeman's Volunteers (S Lakeman, 1880, pp 93-4, 103).

After his initial setback and the shock defeats suffered by the British, Smith set about regrouping and regaining Fort Armstrong, Elands Post, Shiloh and Whittlesea. By June 1851 he had amassed a sufficiently large force at Alice, the 1st Division commanded by Major Gen Henry Somerset, to attempt going on the offensive against the Xhosa in their Amathole mountain stronghold. The newly-arrived 74th Regiment formed a major part of this Division. The attack on the Amatholes by the 1st Division was part of a broader offensive. The 2nd Division under Col Mackinnon undertook simultaneous operations further to the east, in two columns. One, commanded by Mackinnon, marched from Gwili-Gwili along the left bank of the Keiskamma River. The other, under Lt Col Michel, proceeded to Keiskamma Hoek. Troops from the Fort Cox garrison harassed Xhosa in the valleys of the Keiskamma River (Lakeman, 1880, pp 54-5). The 74th Regiment was to bear the brunt of the fighting undertaken by the 1st Division.

By the time the Highlanders came to engage the Xhosa in 1851, the Xhosa had evolved an altogether more sophisticated form of guerilla warfare to overcome the technology and tactics of the British. In precolonial times and the early wars warriors had carried cowhide shields and spears. The main tactic was encirclement of the enemy. As early as the War of Hintsa in 1835 the Xhosa largely abandoned cowhide shields when these proved to be ineffective. During the successive wars of dispossession, open encircling engagements gave way to guerilla warfare from mountain and forest strongholds, ambushes on wagon trains and general harassment of columns and patrols. The Xhosa adopted firearms, either captured from the British or traded with the Colony, whenever they could. The assegai (of which there were numerous patterns), which some British officers claimed could be accurately thrown 50 metres, was still carried. Since the effective range of muskets at the time was only 60 to 70 metres, the advantage enjoyed by the British was not overwhelming (I Knight in P B Boyden, A J Guy and M Harding [Eds], 1999, p 21).

The 74th Regiment, for its part, also made some adjustments for campaigning in the Eastern Cape. In Grahamstown their uniform was altered to make it more suitable for warfare on the frontier. The heavy jackets were replaced with short, dark canvas blouses; 'feldt-schoen' and lighter pouches of untanned leather were issued to the men; and broad leather peaks were fitted to forage caps. Officers kitted themselves out with pack-horses, patrol tents, camp-kettles, saddle bags, African servants and many other necessities (W R King, 1853, pp 27-8). T J Lucas of the CMR, who also fought in the 1850-53 war, left a humorous, but no less convincing, account of changes to military uniform and equipment (T J Lucas, 1878, pp150-1): 'In addition to my ordinary undress uniform I wear a light forage cap and a comfortable patrol jacket, and besides my cavalry sword I carry a double-barreled gun, attached to the saddle in a leathern bucket on the right side, a pocket pistol loaded with French brandy is slung over my shoulders, a slice of jerked beef in lieu of a revolver in my holsters, and a broad strap buckled round my waist supports a good sized pouch for bullets and cartridges, and smaller one for caps, my military cloak is rolled on the saddle in front, and a tin-pot or "tot" in colonial parlance, adorns the horse's crupper'.

Notwithstanding these changes to equipment the 74th were, in the opinion of one of their own officers, at a disadvantage to the Xhosa (King, 1853, p145): 'The advantage ... the [Xhosa] possesses on [his home] ground over regular troops is immense; armed only with his gun, or assegais, free and unencumbered by pack, clothing or accoutrements; his naked body covered with grease, he climbs rocks and works through the familiar bush with the agility of the tiger, while the infantry soldier, in European clothing, loaded with three days' rations, sixty rounds of ball cartridge, water canteen, bayonet and heavy musket, labours after him ... '

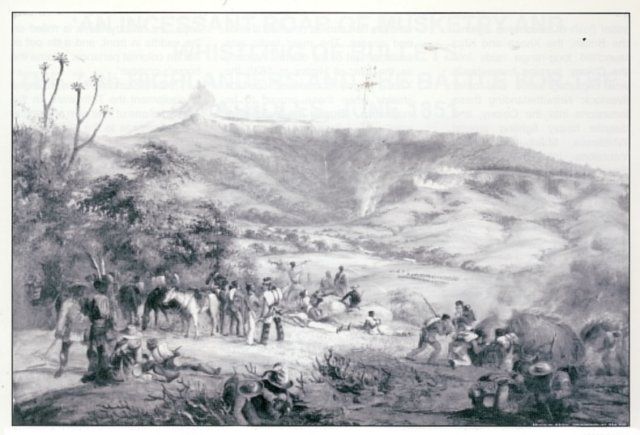

Thomas Baines' depiction of the attack on 26 June 1851. In the foreground a mixed bag of officers, burgher levies, Mfengu, Khoi levies and soldiers of the 74th

Regiment are shown burning Xhosa huts and watching the 74th Highlanders attacking the Xhosa and Khoi positions on Zingcuka ridge (the first table land on the

right).

The Xhosa and Khoi withdrew into the forest and the 74th were forced to pursue onto the second ridge, before they returned at nightfall to bivouac in the Amathole basin

near the stream. Unlike some of his other depictions of battles during the 1850-53 war, Baines was an eye-witness to the attack. (Source: MuseumAfrica MA 290).

24 June 1851

On Tuesday, 24 June 1851 some 2 000 men of the 1st Division, consisting of artillery, infantry and irregular forces, left Fort Hare at Alice. Baines provides a vivid description the column, 'troops mingled with guns, baggage and artillery wagons, pack horses, drivers and camp followers of both sexes and all colours, were emerging, in obedience to a discipline that seemed capable of creating order out of chaos and old night. .. ' (T Baines, Volume 2 [edited by R F Kennedy], 1963, pp195-6). The bulk of the force consisted of troops from the 74th Regiment (under LieutenantColonel John Fordyce) and the 91 st Regiment (under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William Sutton), Cape Mounted Riflemen (CMR), Mfengu and European levies, with two field pieces, all under the overall command of Maj-Gen Henry Somerset (J McKay, 1970, p 31). They marched in an easterly direction, towards a peak now known as Iron Ridge, but variously referred to at the time as the 'Victoria Heights', 'Sevenkloofs mountain' and 'Little Amatola' (King, 1853, pp 45-6; Baines, 1963, p196). The large force set up camp on the small Kwezana stream on the eastern side of the Tyhume valley, watched by a group of Xhosa on the nearby Victoria Heights, the long ridge that separates the Tyhume valley and the Amathole basin.

25 June 1851

The following morning Baines, with an escort, went off to sketch the camp. From his vantage point he saw some of the Mfengu auxiliaries exchanging shots with the Xhosa on the slopes of the Victoria Heights, but without apparent effect on either side (Baines, 1963, p196).

26 June 1851

At 05.00 on Thursday, 26 June 1850, the British left the camp, and climbed the ridge separating the Tyhume valley and Amathole basin as noiselessly as possible in the dark and cold of winter. The force halted in a long line facing the Amathole basin. A small patrol was sent to reconnoiter the Victoria Heights, on their right flank. Meeting determined resistance from the Xhosa, the patrol had to be assisted by two companies of the 91st Regiment and three companies of the levies (King, 1853, p 47). Whilst these engaged the Xhosa on the right, the rest of the force turned its attention to the Xhosa and Khoi who occupied the Zingcuka ridge on the opposite side of the Amathole basin, in the vicinity of what is now the Zingcuka Forest Station on the Wolf Ridge road between Hogsback village and Keiskammahoek. Looming large behind this is the imposing Hogsback peak (frequently referred to by the British at the time as the 'Great Amatola'). From his vantage point Capt King noted that the smoke of Xhosa fires was visible on the lower ridge across the Amathole basin; and on the left 'towered the lofty peak of the Hogsback, the highest point of the whole chain; and below it lay a finely wooded ravine, down the centre of which foamed a milk-white cataract, the dark forest stretching away on either side, and filling the kloof' (King, 1853, p 47).

The general plan Somerset appears to have adopted was to send the 74th down the slope and across the upper part of the basin to attack the Zingcuka ridge. The cavalry and packhorses were to make a detour to a point about a mile to the left where the descent was not so steep. At the same time the rest of the force (mainly the 91st Regiment) was to sweep through the basin and climb the ridge a short distance to the east. Once they attained the top of the ridge, the 74th Highlanders were to swing right and link up with the 91 st Regiment. As they went, the British and Mfengu made a point of burning the Xhosa homesteads they came across. Acting on these plans, the 74th descended the rather precipitous slope into the basin, crossed a flowing stream, halted and formed up in 'column of sub-divisions', with No 1 Company about 100 metres ahead of the column (McKay, 1970, p 34; King, 1853, p 48).

As they crossed the basin they noticed hundreds of Xhosa warriors and their Khoi allies gathering at the top of the cliffs on the Zingcuka ridge. The ridge rises precipitately from the floor of the basin. Topped with grey cliffs, it forms a superb natural fortress. In the meantime, the second column, consisting of the 91 st, were scaling the heights and engaging the Xhosa to the right of the 74th, about a mile away. The Mfengu moved on the left and right flanks of the 74th, skirmishing and burning huts (King, 1853, p 74).

The 74th marched in parade ground order until they finally reached the point where they started the steep climb. To their surprise the Xhosa and Khoi on the ridge allowed them to advance some way up the slope before sporadically opening fire. Halfway up the hill, the bugler sounded the call for No 1 Company to lie down and the column which now formed a line in the rear of the skirmishers, advanced, with each company firing over the skirmishers and got into position (McKay, 1970, p 34). The whole Regiment then advanced up the slope. It took the 74th another quarter of an hour, clambering up the rocks, now under heavier fire, to eventually reach the ridge. Capt King graphically described how the Xhosa opened fire on them from the rocky crags of the 'natural citadel': 'Showers of balls whistled past us, with the peculiar ping whit so well known to those who have been under fire ... For a quarter of an hour there was an incessant roar of musketry and whistling of bullets, (King, 1853, p 49).

A private fell, shot through the foot. As they neared the top, they scrambled up the rocks on hands and knees. Another man fell shot through the arm and side, followed by another, also wounded. Two more received wounds (one with a shattered hand and another with a head wound). Lt Bruce was wounded in the arm and a sixth man fell badly wounded in the leg (King, 1853, p 49). The 74th gained the summit and advanced across the flat grassland, with the Xhosa and Khoi withdrawing into the dense forest a few hundred metres behind the position.

After a short breather, No 1 Company was again ordered to the front in skirmishing order and the soldiers of the 74th charged into the forest, firing in the gloom of the thick bush at their unseen enemy. The soldiers skirmished from tree to tree, from rock to rock. Two soldiers (Cumming and Pearson) were fatally shot. On the edge of the forest on the ridge they burned many huts and 'hartebeest huisies', some of which had wounded Xhosa inside (King, 1853, pp 50-1).

Map showing route taken by the 74th Regiment during the battle for the Amatholes, 24 June - 5 July 1851.

(Source: Route derived from various contemporary sources drawn onto Google Earth image).

The 74th wheeled to the right and joined up with Somerset and the 91st who had gained the ridge from the grassy slope on the right without opposition. The 74th lost three men killed and five wounded in the attack on the Victoria Heights. For the first time in nine hours they halted, piled arms and rested. It was 14.00 and no-one had breakfasted yet. There was, however, no water and their canteens were empty. The men tried gnawing their black biscuit with lips that were parched and blistered from the sun (King, 1853, p 51). The bodies had been left where they had fallen on the first ridge. Whilst they were resting they noticed a party of Khoi and Xhosa below them where the 74th dead lay, stripping the corpses. The Khoi mutineers from the CMR, some of whom were still clad in CMR uniform, appear to have exploited the confusion of battle. Some approached Lt Gordon of the 74th and asked for tobacco and cartridges. Before the British could respond, they fired and rushed into the bush - hitting a soldier in the legs, who later died (McKay, 1970, p 40; Baines, 1963, p 200). Baines noted that he was personally told by Gordon that whilst watching the edge of the bush, some of the rebels came and smoked with his men and asked for percussion caps (Baines, 1963, p 200). During this time some of the Khoi mutineers and rebels apparently engaged General Somerset in discussions about surrender. Lt-Col Sutton was sent off by Somerset to parley with a group of about fifty or sixty at the edge of the wood. They indicated they wanted time to collect their families. When Somerset insisted they immediately surrender, they disappeared back into the forest (King, 1853, pp 52-3). McKay presents a somewhat less flattering picture of the negotiations. According to him, the British saw some of the CMR mutineers on the ridge where the British bodies lay. Somerset and his orderlies rode over and engaged the mutineers in conversation whilst some carried on looting the dead, to the chagrin of Fordyce. They then separated and rode back (McKay, 1970, p 39).

Thomas Baines

Thomas Baines did not advance with the 74th Regiment, but initially stayed on the neck, where he had a good view of the proceedings, and sketched (Baines, 1963, p 197). One of his most familiar paintings showing the Amathole basin and Zingcuka ridge was sketched from this position. The sharply defined lines of the Hogsback peak and cascading waterfall provide good reference points. His detailed illustrations of the battle are complemented by his graphic descriptions of the action (Baines, 1963, p 198): 'The scene below our feet was now a perfect pandemonium of unearthly sounds. A cloud of light-blue smoke through which forms of the men were dimly seen, floated along the valley, marking the progress of the conflict; while the barking of dogs and the occasional screaming of terrified women rose above the savage yells of despair or shouts of victory and the incessant rattle of fire-arms discharged as fast as they could be loaded'.

Even from his vantage point on a large rock, Baines was not isolated from the fighting. A bullet sang over his head whilst he was sketching (Baines, 1963, p 198). After completing his sketches, Baines joined Somerset and his entourage. They climbed the Zingcuka ridge to the right of where the 74th had attacked, which they reached 'after an hour's hard work, in which we were sometimes literally 'obliged to drag our horses' (Baines, 1963, p 199). They met up with the 74th in the open area above the ridge. Baines makes the telling point that the 74th received the bulk of their losses in the advance up the steep slope. The Mfengu who advanced up a similar slope, by contrast, suffered no casualties, 'disregarding military order and darting from cover to cover as they advanced, [they] reached the heights without losing a man' (Baines, 1963, pp 200-1). He makes the further point, omitted by both King and McKay, that the Mfengu on the right flank attained the heights first and drove off the Xhosa. The 74th, on reaching the ridge, fired on the first Blacks they saw, thinking they were retreating Xhosa (Baines, 1963, p 201).

The Xhosa forces were, however, not defeated. From their vantage point on the heights, the British saw the Xhosa assembling on the tableland through which the 74th had just advanced. The 74th were again ordered into the forest to clear the Xhosa off the ridge below. Whilst the rest of the column cautiously followed, the soldiers of the 74th made their way through the dark forest. They emerged into the open space on the Zingcuka ridge, passing the naked body of one of their dead in the forest (King, 1853, pp 52-3).

Once the rest of the column had joined them, they began to scrape shallow graves with their bayonets to bury their three dead. A party was sent back to recover the body seen in the forest, but the Xhosa subjected them to harassing fire from the cover of the forest, wounding one man in the knee (who later died whilst undergoing amputation) (King, 1853, p 53). The 74th returned fire and followed up, but the pursuit was not very determined as light was fading fast. Having been active since 05.00, the exhausted soldiers were ordered to return to the Amathole basin where they were to camp for the night. The 74th descended by the same route they had ascended in the morning. Initially they tried to trick the Xhosa into thinking they were going to stay on the ridge near the rocks. McKay, who was with the main body of the 74th who were first to withdraw from the Zingcuka ridge, noted (McKay, 1970, p 47): 'The day was fast waning when we reached the basin, the shadows of the surrounding mountains were extending far towards the east; the smoke of many little fires of the enemy in the bush curled as it ascended in the calm evening atmosphere, and the wild "azapha" (come here) still continued to ring through mountain and glen from the [Xhosa] hordes, as we prepared our evening meal by the bivouac fires.'

The No 1 Company skirmishers were left to cover the withdrawal, which was completed in the moonless dark, amidst lots of firing. Capt Duff requested permission to go to their aid, but Somerset refused. The Company then dashed down the slope at 'helter-skelter, pell-mell pace down the ridge, as fast as their legs could carry them, over rocks, stones, bushes, and long grass' until they were out of range. They arrived with one officer wounded (McKay, 1970, pp 41,47-8).

The Xhosa re-occupied the ridge from which they had been dislodged earlier in the day and, according to a sergeant in the 74th Regiment, dug up the bodies of the British soldiers and hurled them after the British (McKay, 1970, p 41; Baines, 1963, p 200).

At midnight, when it was discovered that there was no water left in camp, Capt King, as duty officer, had to lead an armed party to the stream about 250 metres away to fill canteens. To compound the confusion, on their return the Mfengu auxiliaries fired on them in the dark (King, 1853, pp 55-6).

27 June 1851

The next morning, 27 June 1851, dawned dull and misty. The Xhosa were still on the ridge and taunted the British soldiers, mockingly calling the Highlanders 'tortoises' - an insult which probably had as much to do with their slow pace as the geometric pattern of their tartan trews (King, 1853, p 57). The wounded were sent off under escort to the camp at the Kwezana stream, together with some women prisoners (Baines, 1963, p 201). The soldiers made ready to climb the heights again and ascended at three different points in the early morning darkness. The Mfengu ascended about a mile away on the left; the cavalry on the right. The 74th, in darkness, went up a somewhat steeper and shorter middle route (to the right of where they had attacked the day before (King, 1853, p 57). On the ridge, still enveloped in thick mist, they stopped and lit fires to warm chilled hands and feet until the mist eventually lifted. They heard voices and, as a blast of wind lifted the mist, found a group of Xhosa within 'pistol-shot' of them. By the time they had scrambled for their weapons, the Xhosa had disappeared into the forest (McKay, 1970, p 48).

They then moved off to the next ridge, but found the going very heavy. 'The men, loaded with their rations, blankets, great coats, firelocks, and sixty round of ball cartridge, were so fatigued by the overpowering heat of the noonday sun, that the whole column constantly halted, literally unable to move for the moment' (King, 1853, p 57). Groups of Xhosa watched the proceedings, but did not attack. Once on the ridge, they marched off in an easterly direction, into the Zingcuka or Wolf River valley. From the heights they could see Fort Cox (McKay, 1970, p 49). Descending into the Zingcuka valley, the Mfengu plundered a village of considerable quantities of maize, discovered in underground pits; and set fire to the huts (King, 1853, p 57).

The 74th formed a hollow square and piled arms, preparing to bivouac for the night at the head of the beautiful valley (McKay, 1970, p 50). In the meantime, Somerset and some of the CMR and Mfengu proceeded along a stream where they engaged a party of Xhosa in a brisk fight on the ridge adjoining Mount McDonald. They then descended into the Keiskamma valley, along the 'Linguey stream' (possibly the Lenye) and returned after a long march at about dusk (King, 1853, p 58). As soon as darkness fell, the Xhosa crept nearer and began to fire long shots into the groups of soldiers huddled around their fires, wounding an officer of the levies. They became so aggressive that at length a skirmishing party had to be sent out to disperse them (King, 1853, p 58).

28 June 1851

Shortly after dawn on 28 June, the column moved out of the Zingcuka River valley and climbed Mount MacDonald, reaching the summit at about 10.00. While the main body rested, a group of the levies was sent back into valley to intercept cattle that had been seen (King, 1853, p 59). From the heights of Mount McDonald, they could see the Xhosa emerge and cover the bivouac site. They could also discern Keiskamma Hoek, with the white tents of the 6th and 73rd Regiments of the 2nd Division (King, 1853, p 59; McKay, 1970, p 49). The levies moved about skirmishing and burning Xhosa huts. They returned with 350 head of cattle and most of the column made their way back to where they had camped in the Amathole basin on the night of 26 June (King, 1853, p 59). The 91 st were left to cover the withdrawal of the Mfengu and did so without incident until just before they began the descent into the Amathole basin, when they were attacked (King, 1853, p 59).

29 June 1851

At 08.00 on Sunday, 29 June, 'unwashed and unshaven, with tattered clothes and rusty arms', the column marched for the standing camp at the Kwezana stream. For the next three days they recuperated and waited for supplies from Fort Hare (King, 1853, p 60).

2 July 1851

On Wednesday, 2 July, the whole process started all over again. They moved into the Amathole basin and climbed another part of the ridge linking Hogsback and the Victoria Heights and again attacked Xhosa and Khoi positions, at the southern point of the Hogsback (King, 1853, p 60). They gained the ridge after a tedious climb and looked down on numerous scattered kraals in the bush on which the Mfengu were advancing, 'firing, yelling, and setting everything combustible in flames' (King, 1853, p 61). In the meantime, the 91st and a party of the European levy attacked the southern part of the Hogsback, burning huts and driving the Xhosa off towards the Tyhume peak. Two large settlements, which had previously escaped the notice of the British, were burnt. As they moved through the valley, they unexpectedly came across the homestead of Chief Oba (one of the sons of Chief Tyali). His homestead was burnt and a number of women and children were taken prisoner, before the British forces returned to the Kwezana (King, 1853, p 61).

3-4 July 1851

Grazing had become so depleted around the camp by this time that they were obliged to shift camp to the Ncera (or Yellowwoods) stream about three miles away from the Kwezana. On 4 July the 74th rested whilst the Mfengu were sent to loot and burn deserted homesteads, returning laden with loot (King, 1853, pp 62-3). The operation was now winding down.

Conclusion

On Saturday, 5 July, the whole force marched back to Fort Hare and camped on the plain outside the walls of the fort. On 24 June the column had set out boldly from Fort Hare to the strains of 'Hieland Laddie' and 'Over the Border' from the band of the 74th Regiment (King, 1853, p 44). The operation, which seems to have only been planned for three days, had taken nearly two weeks (Testimony of wagon driver, Mr Joseph B Amos to George Cory, 1908, in M Berning (Ed), 1989, P 143). The soldiers returned tired, dirty and sun-burnt, with tattered clothes, rusty weapons and depleted numbers. Official statistics put the British losses at three rank and file killed and one officer and nine men of the 74th wounded; and one sergeant and two men of the levies killed, with one officer and four men wounded (Cape of Good Hope Parliamentary Papers, 'Correspondence with the Governor of the Cape of Good Hope Relative to the State of the Kafir [sic] tribes and the Recent Outbreak on the Eastern Frontier of the Colony, 1852', p 65: Enclosure in Despatch No 9, Somerset - Cloete, 28 June 1851. These figures are lower than the number of deaths described by McKay and King).

As far as the British were concerned, the battle for the Amatholes was over. Smith glibly reported to Earl Grey in England that '[t]he general and combined movements into the Amatola Mountains which I have long had in contemplation has been effected with the success I anticipated.' Over 2 000 cattle, 42 horses and nearly 1 000 sheep and goats were seized from the Xhosa, large stocks of corn were captured or destroyed and large numbers of homesteads were torched. But in the same report Smith admitted that it had 'no perceptible effect as regards the termination of hostilities' (Cape of Good Hope Parliamentary Papers, 'Correspondence with the Governor of the Cape of Good Hope Relative to the State of the Kafir tribes and the Recent Outbreak on the Eastern Frontier of the Colony, 1852', pp 61-2: Despatch No 9, Smith - Grey, 3 July 1851). Almost a year later the new governor, Sir George Cathcart, was reporting on similar operations against the Xhosa in the same area (Cape of Good Hope Parliamentary Papers, 'Correspondence with the Governor of the Cape of Good Hope Relative to the State of the Kafir tribes and the Recent Outbreak on the Eastern Frontier of the Colony, 1853', P 118: Despatch No 23, Cathcart Secretary of State for Colonies, 20 May 1852). The soldiers of the 74th, who had hoped to rest on Sunday, were rudely disillusioned. Soon after sunrise the next day, they struck their tents and begun marching west towards the Waterkloof (King, 1853, p 63). Compared to what they subsequently experienced at the hands of Chief Maqoma in the Waterkloof, the battle for the Amatholes had been a Sunday school picnic.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the staff of the Amathole Museum, East London Museum and Buffalo City Public Library for their assistance in preparation of this article. The research was originally inspired by preparations to visit sites associated with the 1850-53 war with the late Gordon Everson in the 1980s. Many happy days were spent, amidst breathtaking scenery, in the convivial company of Tony Step, Gill and Carl Vernon tracking down these historical sites. Appreciation is also extended to MuseumAfrica for permission to use Thomas Baines' painting of the attack on the Amatholes. A special thank you to Linda Chernis, Curator of Images at MuseumAfrica, for very efficiently arranging a copy of the painting.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org