The South African

The South African

Introduction

In the background of our times, an old issue simmers. For more than a hundred years, there has been agitation about the trial of Breaker Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton during the Boer War (1899-1902) and there is currently a renewed effort to have their convictions and sentences overturned. But what if the court got it largely right? Here we re-examine some of the issues.

Jim Unkles, a military lawyer, and Nick Bleszynski, an historian, petitioned the Australian Parliament during 2009 on behalf of the three accused, and petitioned the British Crown at the same time. The petitioners want the trial reviewed, a pardon for the three and the commuting of the death sentences passed on Morant and Handcock, even though they were executed in 1902 (Unkles, James, 'Petition to the Speaker and members of the House of Representatives').

The Attorney-General, Robert McCleland, referred the Australian petition to Britain, saying that Australia had no jurisdiction in the matter (McCleland, R, Letter to Ms J Irwin, Chair, Petitions Committee, 8 Feb 2010). The Petitions Committee of the Australian House of Representatives nevertheless held a hearing on the petition on 15 March 2010 and the press continues to provide coverage. The Sydney Morning Herald, for example, carried an article on the petition on 10 July 2010. A week earlier, TV Channel Nine's 'Sixty Minutes' programme gave it considerable air time.

'Breaker' Morant and the Bushveld Carbineers

Before the Boer War began in October 1899, Harry Morant, an educated Englishman with a classy accent and an obscure past, was living in Australia, jackarooing, breaking horses, writing poetry, drinking and womanising his way around the outback (Information on Morant's life and war-time experiences appears in Wilcox, 2002, pp 276-96; Field, 1979, pp 170-4; and Wallace, 1976). He linked his abilities with pen and horse by signing his poems 'The Breaker'. He volunteered to fight with South Australian troops in the Boer War and served his tour of duty. Then he returned to England where, it seems, he and a man called Peter Hunt spent much time in each other's company. Hunt had also served in the South African War and, thirsting for more action, they returned and joined a regiment called the Bushveld Carbineers. It contained many Australians, including Handcock and Witton, but this was not an Australian regiment. It was raised locally in South Africa and subsequent events have no bearing on Australia's official engagement in the war.

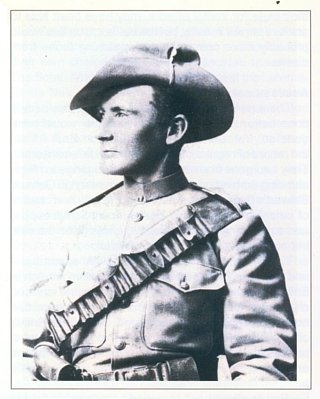

Photograph of Breaker Morant taken in Australia

before his departure for South Africa.

(Source: Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Ref A05311).

A detachment of the Bushveld Carbineers was posted to the remote Fort Edward in the far northern Transvaal, where Hunt was killed on 6 August 1901 in a skirmish with the Boers. After the death of his friend, Morant took command of the detachment. He and the men now under his control behaved in a most un-soldierly manner: They killed prisoners. Most of the victims were Boers who had come in to lay down their arms and surrender.

The Court Martial

Morant and several others were arrested and court-martialled. After a trial which took months to prepare and lasted four weeks, they were found guilty of twelve murders. Harry Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton were sentenced to death, while others received lesser sentences. During the subsequent review of the case, Witton's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He was released after the war following a petition raised in Australia and supported in South Africa.

That the accused killed unarmed men is not in dispute. At their trial, they admitted as much quite forthrightly. Together with their defence lawyer, Major James Thomas, a country solicitor from Tenterfield in New South Wales, they argued, however, that they had been acting under orders. Thomas also pleaded other mitigating circumstances: That Morant had been badly affected by the death of his friend; that he and his men had been suffering from the stress of war; and that the Boers had deserved their fate. The court martial was unmoved by the mitigating pleas and did not accept that they had been acting under orders.

The petitioners now argue that the trial was flawed. It was. The defence counsel had very little time in which to prepare their case, perhaps only a day, after the prosecution had taken months. Major Thomas had never conducted anything of this magnitude, while the prosecuting lawyer was experienced. The petitioners have pointed out many other weaknesses in the conduct of the case and in its aftermath. For example, they found that the court had not been properly directed in law, that the commander-in-chief could not be reached to hear pleas for mercy before the executions were carried out because he was away on campaign, that the men were executed before pleas for clemency could be made to the King, and that they had not been permitted to contact relatives or representatives of the Australian Government to enable them to make pleas for clemency on the accuseds' behalf, and so on. However, while the petition is a lengthy document, it never argues that Morant and his men were innocent. It could hardly do so, given the unabashed, uncontested admissions that unarmed people were killed. Most of the victims had handed themselves in, as they were required to do under the martial law imposed on the district, and were killed in cold blood. In one incident, for example, eight of the victims were made to dig their own graves side-by-side before they were lined up and shot. With the admission of this type of behaviour, no review can absolve the accused of the killings.

The crucial question is whether Morant and his men were acting under orders. In his appearance before the Standing Committee on Petitions on 15 March 2010, Unkles did not address this question. Instead, the petitioners argue that the trial was technically flawed and that this is sufficient cause to justify a pardon. They argue that the convictions were 'unsafe'.

The transcript of the trial proceedings has not been found and this will make a review difficult. After more than a hundred years, it seems equally unsafe now to second guess a court that sat for weeks on a trial. Perhaps, rather than looking at the legal technicalities of the trial, one ought to consider the substantive issue: was there an order to shoot prisoners? In the trial, the defence was unable to produce evidence of a written order. Morant's argument was that the order had been given verbally to Hunt and that it had originated with the commander-in-chief himself, Lord Kitchener.

The shooting of prisoners

Hunt was dead, unable to testify or to be cross-examined, but Major Robert Lenehan, an Australian and superior officer to both Hunt and Morant, was there, facing charges himself for his failure to intervene in the remote Fort Edward when stories of summary executions reached him. He said in evidence that he was unaware of any order to shoot prisoners. Kitchener's secretary was subpoenaed to testify and he, too, denied the existence of any such order, even though the accused had identified him as having passed on Kitchener's order to Hunt.

Relevant as these denials are, they are not the only reasons for doubting the existence of the order. Why would Kitchener, or for that matter any other senior officer, have issued such an order? And why verbally? An order to execute unarmed prisoners would have been highly contentious. If one side in the conflict had systematically executed prisoners, the other side might well have done so too, placing every soldier in the field at greater risk. Most of the men would have appreciated the dangerous implications of such an order.

When the Boers captured soldiers, as they regularly did, they usually set them free after relieving them of horses, munitions, food, boots and anything else that they could use (Reitz, 1929, p 232). They were conducting a guerrilla war, where mobility was the key and holding prisoners did not suit their strategy. Had they become aware that the British were executing prisoners, would they have continued to release captured Imperial soldiers? Lord Kitchener understood the risks, as did his officers and men. An order to execute Boer prisoners would have been unwise, very unpopular with the rank-and-file, and seems most unlikely on these grounds alone.

The events in question occurred near the end of the war, when many of the Boers could see that they had lost the struggle. Hungry, ragged, short of horses and ammunition, concerned for their families, there seemed little point in their continuing to fight and they were surrendering at a steady rate. Kitchener's mission was, of course, to bring the war to a close as rapidly and cheaply as he could. It had already lasted much longer than expected, the cost was many times greater than anticipated, and London was more than impatient for it to end.

Kitchener also had personal reasons for wanting to get it over as fast as possible. He had been promised the position of Commander-inChief of British Forces in India, a prestigious job that he coveted (Pakenham, 1982, pp 492, 561). That position was vacant and Kitchener knew that it would not remain so indefinitely. He feared that he might lose it if he could not extract himself from South Africa soon.

The faster the Boers surrendered, the sooner the resistance would collapse and the war would be over. Shooting Boers who did surrender is an unlikely way to encourage their compatriots to follow suit. Kitchener was no fool and it is hard to imagine that he would have committed such a tactical blunder. Moreover, obtaining a negotiated peace was a pillar of his war strategy and, in negotiations, he treated Boer commanders with respect and dignity. Before the Fort Edward murders, he had shown, and continued to show on later occasions, that he was prepared to be generous if they would lay down their arms. Executing those who did lay down their arms does not fit with his policy.

Further circumstantial evidence exists on a personal level to convince the writer that Lord Kitchener never gave an order to shoot prisoners.

The writer's maternal grandfather was a Cape Rebel, a British subject of Dutch extraction whose sympathies lay with the Boers. At the age of nineteen, he joined them and fought with them against the Empire. After nine months on campaign, his luck ran out and he was captured in December 1901 near Graaff Reinet. In January, the very month in which the Morant trial began, he, too, faced a military court and was convicted of high treason. He, too, was sentenced to death (Report of the Royal Commission into Sentences Passed Under Martial Law, Parliamentary Paper, Nov 1902). Fortunately, there had been misgivings in Britain about the imposition of the extreme penalty on these naive youngsters, especially as the rules had changed after most of them had already signed up. After more than thirty rebels had been executed, questions were asked in Parliament. Kitchener, mindful of the politics, then gave orders that no condemned prisoners were to be shot unless he had personally authorised the execution. From that time onwards, only rebels in positions of authority were executed. Kitchener personally commuted the writer's grandfather's death sentence to life imprisonment (although, like Witton, the young man was released after the war). If Lord Kitchener had really wanted Boer prisoners to be executed, where better to start than with those who, like the writer's grandfather, had already been tried and sentenced to death? Instead, he was lenient. Morant's victims, on the other hand, had had no trial.

Yet, there is one aspect of the war where Kitchener trod dangerously. When the Boers were running out of everything, surviving by raiding Imperial convoys or encampments, they also took clothing. The result was that some took to the field dressed in British khaki. When he heard of this, Kitchener was apparently outraged and ordered that Boers caught in British uniforms should be shot.

However, none of the sources seen by the writer indicate that Morant or his co-accused offered this as a reason for shooting their prisoners, probably because there were too many witnesses who would refute such a claim. There was one notable exception - Morant said that their first victim, Visser, had worn an item of clothing that he had recognised as Captain Hunt's. Visser was a youth whom they had wounded in a skirmish and who, on account of his injuries, was unable to escape with his compatriots. Instead of offering medical assistance - routine procedure on both sides - Morant executed Visser. The killing of this lad, wounded and in distress, disgusted the men under Morant's command.

British Army records

The war was conducted with a mature, smoothly functioning bureaucracy at the time that the events in question happened. Orders were issued in writing. Copies were retained and originals filed by the recipients. If Lord Kitchener had issued a verbal order, it would have been irregular and unusual. He had more than 200 000 troops under his command at that time, spread widely over most of South Africa. It seems far-fetched that he could or would have attempted to reach them all, or even most, by word of mouth. Imagine how unreliable such an order would have been by the time it reached the front line. It seems equally far-fetched that he would have issued an order to take no prisoners just to the small detachment under Hunt at Fort Edward, a place where he never set foot and which was of no consequence in the overall scheme of things. What could be achieved by such an isolated practice in such an isolated place? Typically, orders to the region would have been transmitted by telegraph to the regional commander at Pietersburg, Lieutenant-Colonel Hall. Hall would have passed them on to Major Lenehan (also in Pietersburg) who would then have sent specific orders on to Captain Hunt and Lieutenant Morant at Fort Edward. Copies would be kept at every stage. That is how the process worked.

Most officers would have refused to accept, let alone implement, a verbal order as controversial as that calling for the shooting of prisoners. They would have asked questions and insisted on getting the order in writing. To do otherwise would have been to expose themselves to court martial, as the case of Morant and his co-accused so clearly shows. It would also have exposed them and their men to summary execution should they themselves be captured by the Boers.

It is very unlikely that the order ever existed. There is an immense amount of archival material about the Boer War still in existence. Lord Kitchener's papers may be read in the excellent British National Archives at Kew, along with thousands of other Boer War documents. Regimental museums, university libraries and other institutions around the world, including the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and universities, archives and museums in South Africa, also hold extensive records. Soldiers kept diaries and many wrote letters home that still exist. Many books appeared in the years following the war in which men on both sides recounted their war-time experiences. After the war, an exhaustive Royal Commission examined every aspect of the war and the record of its proceedings runs to 2 015 pages.

In all this material, one finds men and officers freely debating the strategies and policies followed during the war. Sometimes they are critical of the orders they received from Lord Kitchener's Headquarters. One finds, for example, a number expressing reservations about the wisdom of Kitchener's 'scorched earth' policy. Many, one must presume, would have remarked on an order as controversial as that of shooting prisoners.

If the case is to be made that Lord Kitchener did issue an order to execute unarmed prisoners, the voluminous material at our disposal would seem to be the place to look for it. Yet, although the Morant case has been controversial from the date of his trial and although historians have researched the subject and written about it for a hundred years, there has been no authoritative confirmation to date that the order existed.

It was common practice for the Boer commanders to write to Lord Kitchener and to his predecessor, Lord Roberts, in protest when they considered that British conduct had overstepped the line of civilised warfare. This correspondence was reproduced in Parliamentary papers and is readily available to researchers. The Boers protested, for example, when Commandant Scheepers was captured, courtmartialled and executed. The British found him guilty of multiple crimes, including the murder of civilians. The Boers thought he should be treated as a prisoner of war. If there was a general order to shoot prisoners, we may be sure that the Boer commanders would have known about it and protested. The writer is unaware of any such protest having been made.

Evidence was produced at the Morant trial to indicate that Boer prisoners had been shot elsewhere in South Africa. The history books show that there were rumours in other places of an order to kill prisoners. However, no confirmation of such an order has been uncovered and the other killings appear to have been isolated events, equally reprehensible. For their part, ill-disciplined Boers also killed prisoners, especially local black people found to be assisting the British. They, too, had no authority to do so. Several were captured, tried, convicted, condemned and executed, Scheepers being one of these.

All courts martial involving serious charges were referred to the Judge Advocate General for review of the transcripts of the proceedings and endorsement by the King. If the verdict seemed unsafe, the confirmation of the sentence was withheld. The Boer War records of the Judge Advocate General are in the British Archives and they show that, in rare cases, confirmation of court martial sentences was indeed withheld (British National Archives, RefWO 90/6). The Morant case is also listed there, the allegations being the most serious levelled against Imperial soldiers during the entire war. Owing to the seriousness and politically embarrassing nature of the offences, the file was embargoed for 75 years, but it can now be read and it confirms that the trial was reviewed and that the sentences were confirmed.

Conclusion

The 'Breaker' Morant case represents the worst instance of atrocities committed by soldiers of the Empire in the entire Anglo-Boer War. The events were followed by a flawed court martial but there is considerable, if circumstantial, evidence that the verdict reached in that trial was probably correct: There probably was no order to shoot prisoners and the accused were guilty of murder.

Some concessions can probably be made for Handcock and Witton. They were, after all, acting under Morant's orders. Handcock was a simple smithy from Bathurst in New South Wales and easily led. Witton, who had a lesser part in the killings, was spared the death sentence. For Morant, however, it seems that the court martial verdict and sentence should stand until there is evidence to the contrary.

Craig Wilcox, in his authoritative history of Australia's involvement in the Boer War, deals extensively with the Morant case and finds no reason to challenge the court's original decision (2002, pp 276-96). He shows, however, that in this unfortunate affair there are Australian heroes who should be celebrated. They are the rank-and-file Australians who served under Hunt and Morant and who were disgusted by the conduct of their officers. Led by Robert Cochrane from Coolgardie, WA, they blew the whistle, testified against the perpetrators and assisted in bringing the killings to an end. In doing this, they risked their lives because Morant executed witnesses. Australians should honour them.

A new development

In November 2010, shortly before this article went to press, a spokesman for the British Defence Secretary, Liam Fox, announced that the British Government had rejected Unkles' petition and would not reopen the Morant case.

Bibliography

Field, L M, The Forgotten War (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979, ISBN 0 522 84149 x).

McCleland, R, Letter to Ms J Irwin, Chair, Petitions Committee, 8 Feb 2010.

Pakenham, T, The Boer War (Futura, London, 1982, ISBN 0 7088 1892 7).

Reitz, Deneys, Commando (Faber & Faber, London, 1929).

Unkles, James, Petition regarding the convictions of Morant, Handcock and Witton, Australian Hansard, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Petitions, 15 March 2010.

Wallace, R L, The Australians at the Boer War (The Australian War Memorial and the Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1976, ISBN 0 642 99391 2).

Wilcox, Craig, Australia's Boer War (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002, ISBN 0 195516370).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org