The South African

The South African

In 1967, when the writer turned sixteen, he registered to do national service with the South African Defence Force during 1969. The previous 'ballot' system, whereby one's liability for national service was determined by whether or not one's name was 'drawn out of a hat', had been replaced by universal conscription of all white males. In due course, the writer was notified of his deployment in the Administrative Services Corps, which was a disappointment, as both his father and one brother had served in the Transvaal Horse Artillery.

January to March 1969

In January 1969, having completed his matriculation examinations, the young Martin Glass, together with a number of other 'rookies', reported for duty at the Johannesburg Railway Station. They travelled by train to Voortrekkerhoogte, just outside Pretoria, a relatively short distance from their hometown of Johannesburg. They were introduced to army life at Services School in Voortrekkerhoogte, near the Army College, where they underwent their three month basic training.

The writer was a physically fit seventeen year old and, having been a Student Officer in the Cadet Corps, he coped well with the rigorous drill routines and physical exercises, but sunburn and heat exhaustion were something of a problem for him and his fellow 'rookies'. Not surprisingly, he developed a healthy appetite and found the army food to be pretty good. He certainly never went hungry.

There was a large entertainment hall and a canteen at Services School, both efficiently run by a Staff Sergeant Slabbert, who had a good heart under a gruff exterior. Staff Slabbert, as he was called, was always there to sort things out and arranged film shows and other entertainment for the national servicemen during their stay at Services School.

A big hurdle for all of them was, of course, adapting fairly rapidly from being pampered schoolchildren to being military personnel under military discipline. Something that the writer remembers distinctly was that everything around him seemed to date back to the Second World War (1939-1945), be it the accommodation, the uniforms and equipment issued to the men or, in fact, the entire milieu of which they were now a part.

April to June 1969

After completing their basic training at Services School, they had a passing-out parade and received their musterings. The writer was mustered as a pay clerk attached to the Chief Paymaster, South African Defence Force, located in the Presas Building diagonally opposite the Pretoria Railway Station. He was deployed to the Subsistence & Transport Department, run by Lieutenant (subsequently Captain) Sakkie de Jonge, who was an absolute gentleman. The writer worked directly under Sergeant Wilkins, a veteran of the Second World War, who, although pleasant, was a fairly demanding superior and taught him the rudiments of bookkeeping.

Upon deployment to the Chief Paymaster, the 'rookies' had all been promoted to the rank of lance-corporal but, after three months and somewhat to their surprise, the writer and several of his buddies (of average age seventeen or eighteen years) were summoned before an Officer Selection Board and they were subsequently all promoted to the rank of second-lieutenant.

Martin Glass on National Service, 1969.

July to September 1969

From occupying barracks at Details Base, near Defence Headquarters and adjacent to the notorious Pretoria Central Prison, the young officers were transferred, in a state of euphoria at their seemingly miraculous elevation from the ranks, to an officers' mess in Voortrekkerhoogte. This move resulted in an instantaneous improvement in their living conditions, not least of all receiving morning coffee and having their shoes shone by an aged and somewhat surly batman named Jack, who the writer is convinced was a veteran of the Second World War.

An event of note during July was the Apollo 11 moon landing. Unfortunately, unlike the rest of the world, South Africa did not yet have television.

October to December 1969

The writer and his friends then moved to a new officers' mess adjacent to Defence Headquarters, where each man had a private room and their meals were prepared by a professional chef, who also catered lunches at the mess for the 'top brass' from Defence Headquarters. Prior to the young officers taking up their new accommodation, the former residents, a group of students, had become so incensed on hearing that the Army was moving in that they had dumped an ageing Volkswagen Beetle into the swimming pool. The motor vehicle still languished there when the writer and his friends arrived. Upon their promotion, their army pay had increased from 50 cents per day to the princely sum of R1 ,50 per day. Thus, the young one-pippers lived a good life, working hard, but not too hard, and were able to spend every weekend at home in Johannesburg.

It was at that time that thewriter was introduced to information technology, then still in its infancy. The Chief Paymaster had recently installed an IBM mainframe computer, and one of the duties of the young 2/Lt Glass was to write up forms to be 'punched' by a 'punch lady' on to a 'punch card', which was then fed into the computer. Occasionally, he was called upon to stand as Assistant Guard Officer at Defence Headquarters and, on one such occasion, a Saturday, he remembers hearing the wailing of ambulance sirens due, it turned out, to the collapse of a grandstand at Loftus Versveld Rugby Stadium and consequent injury to the unfortunate spectators.

The writer had volunteered for twelve months' service, as opposed to the usual nine months, so that he would not have to attend annual camps, according to an undertaking by the SADF. On completion of his national service in December 1969, he was looking forward to attending university the following year, but felt a definite twinge of regret at taking leave of the friends that he had made during his service.

The writer found national service to be an enriching experience which admirably bridged the gap between school and the real world and invested him with lasting qualities of discipline, maturity and tolerance.

January to April 1977

In 1977, when South African forces were in action in cross-border operations in Angola during the Border War, the writer was recalled to his unit, which had been renamed, somewhat grandly, the Finance Corps, to help sort out problems that had arisen with regard to the payment of the troops on active service and their dependants back home.

Apart from the inevitable computer software glitches, another problem was that the personnel on active service, who earned R 1,33 per day, were allowed to retain R1,00 for themselves (which they invariably did) to pay for beers and other goodies. The wife, in consequence, was left with the impossible task, even then, of feeding, housing and clothing herself and the children on 33 cents per day, hence the frantic and usually abusive telephone calls that had to be fielded from distraught wives.

Now men in their midtwenties, many with university and other qualifications, the writer and his friends found it quite difficult to readjust to the military way of life. They were also informed that their previous appointments as second lieutenants had only been temporary and that they would revert to the earlier rank of corporal. Despite these setbacks, they served out their three month stint to the best of their ability. While some might consider them to have been mere pen pushers, the writer believes that, given the importance of a soldier's pay, he and his friends made a significant contribution to the welfare of military personnel and their dependants.

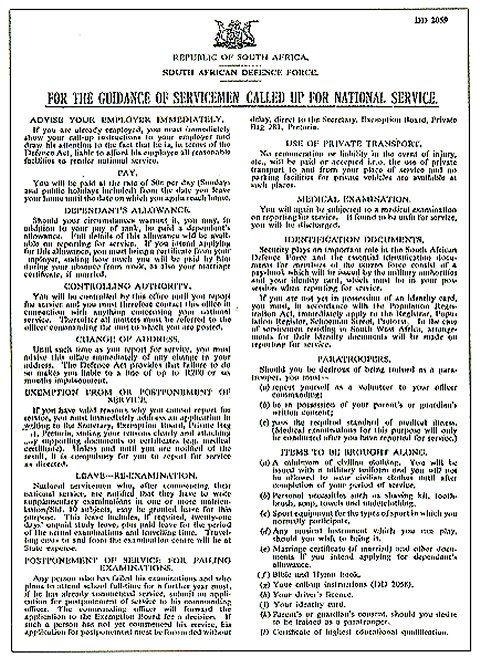

Guidelines issued to young South African men

called up for National Service in the late 1960s.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org