The South African

The South African

(This article was originally published in Afrikaans in the Year Book of the Africana Society of Pretoria, No 24, 2007.)

About the author

Janet Lourens was born in Wales and emigrated to South Africa in the early 1960s. She studied at the University of South Africa where she obtained an MA degree in History in 1991. After living for many years in Reitz she co-authored a book together with her husband J A J Lourens, entitled Te na aan ons Hart - Aspekte van die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die Reitz-omgewing. The couple later collaborated on a second book, Voorvaders en Nakomelinge, Lourense, Van Niekerke, Du Plessisse en Prinsloos. Her current interests are local history and genealogy.

Introduction

The 'scorched earth' policy implemented by the British during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) severely affected the north-eastern Free State. As early as September 1900, farms and crops were systematically destroyed while livestock was killed or driven off to prevent the local population aiding Boer commandos. By early 1902 a network of blockhouse lines had been completed, further limiting the commandos' freedom of movement.To the west, a blockhouse line was erected alongside the Transvaal-Cape railway, while the southern line, linking Kroonstad, Lindley, Bethlehem and Harrismith, was extended eastwards along the foothills of the Drakensberg. The area was completely enclosed by an additional line from Wolwehoek in the west via Frankfort and Vrede to Botha's Pass in the east. Reitz and the surrounding area were subjected to 60 000 British troops sweeping back and forth between the fortified blockhouse lines in an attempt to capture General de Wet and his commandos.

Early in the War volunteers from, amongst others, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Russia, had provided medical support for the Boers (Pakenham,1997, p 250). With the fall of the republican capitals most of these volunteers, convinced that the war was over, returned to Europe and, after the annexation of the Free State on 24 May 1900 the British administration refused entry to foreign medical personnel. Thus, by the middle of 1901, the Boers were solely responsible for their own medical services (Andriessen,1904, pp 516-18). Efficient utilization of the remaining personnel required that they be deployed close to the centre of action. As soon as the wounded had recuperated, the medical facility would be closed and the personnel transferred to other areas of military activity.

The hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift

Abandoned farmhouses, which were still habitable, were often utilized as hospitals. With the intensification of military activities in the Holspruit (Vrede) area, the widow of Z J (Zaag) de Jager, who had died at the battle of Platrand on 6 January 1901, offered the dwelling at Bezuidenhout's Drift to De Wet as temporary accommodation for the injured (Kestell, 1976, p 219). The hospital, which opened on 22 October 1901, continued functioning until the end of the war (A 155, Vol 176, Statement by Dr Poutsma, p 1).

North-west elevation of the hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift

as it appears today. (Photo: by courtesy, J A J Lourens).

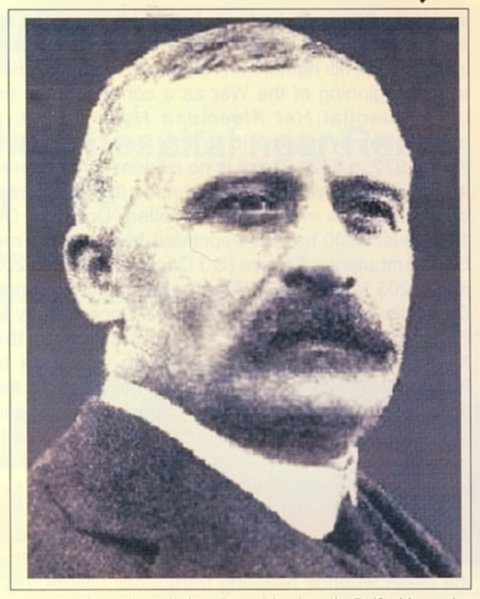

A Dutchman, Hessel Jacob Poutsma, headed the hospital staff. He was an enigmatic character, a journalist and trade union leader whose inflammatory socialist utterances had resulted in his receiving an eighteen-month prison sentence for political incitement in his homeland. He arrived in South Africa at the beginning of the War as a correspondent for the influential Het Algemeen Handelsblad, a newspaper sympathetic to the Boer cause (De Kock, 1972, P 672). There is no evidence that he had any medical training, except perhaps a first aid course, any medical training, except perhaps a first aid course, or that he was entitled to be called 'Doctor'. On 19 August 1900 he was appointed head of the Free State Ambulance Service (S J Odendaal, 1979, p 203 and p 203 footnote 43). After being captured during De Wet's second incursion into the Cape Colony in De Wet's second incursion into the Cape Colony in February 1901, Poutsma was returned to the Netherlands. Eight months later he was back in Pretoria with Kitchener's permission to return to the Free State. De Wet immediately appointed him head of the hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift (W223, PAI/1, Provost Marshal - M Charlier, Acting Consul General for the Netherlands, Pretoria, 26 April 1902). That Poutsma with his limited medical training was able to retain credibility as a medical doctor is perhaps not so surprising. Experienced surgeons agree that the clean wounds resulting from small calibre, high velocity weapons heal easily in the dry highveld air. Serious wounds inflicting extensive internal injuries generally proved fatal (Prof J C de Villiers - J Lourens, 1998, p6).

Poutsma's head nurse was Louisa Susanna (Lily) Rautenbach, daughter of Cornelis Michael Rautenbach (1838-1892) of Golden Gate. After her fiance, Louis Willem Boshoff, had been called up for commando service, Lily decided to join the war effort. She underwent several months' training with the Red Cross in Bloemfontein before commencing work in the field (Oral evidence, Elsabe Crots to J & J A J Lourens, 1998). On 18 November 1901, with just over a year's experience, De Wet appointed her head nurse at Bezuidenhout's Drift. Her assistants were 37 year old Johanna F Raubenheimer of the farm 'Tarragona' near Tweeling, and 21 year old Johanna C Scheepers from Fouriesburg, who later died in the hospital of fever (W223, PAII1, List of Patients).

Two medical orderlies from the Frankfort Commando together with two unknown black men comprised the remainder of the staff. The orderlies were Thomas F D Moll of Vrede and a Dutchman, Arend van Toorenenbergen, of Frankfort (Hobhouse, 1924, p143).

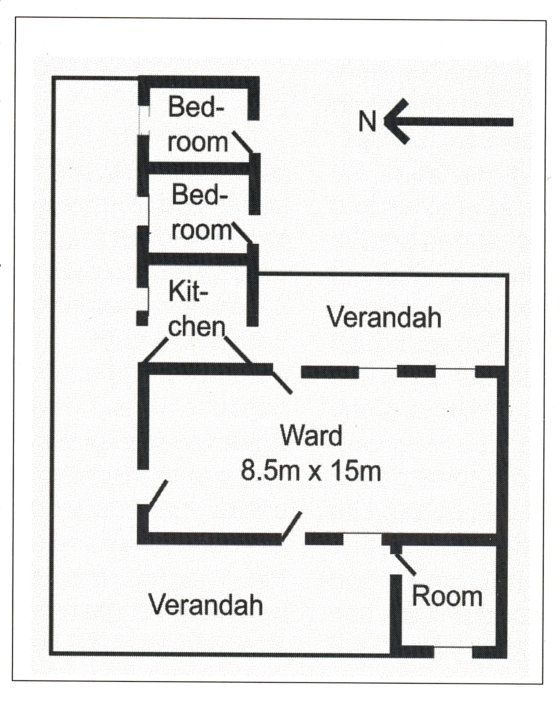

The hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift was situated alongside the road between Reitz and Vrede, approximately 1,5 km west of the Wilge River. In 1901 the river was forded by a good, little used drift, a few hundred metres downstream from the present bridge. The old road, clearly demarcated by a double row of trees about forty metres from the hospital, lies several hundred metres to the west of the current road. Three stone buildings, together with an incomplete corrugated iron structure, comprised the farmstead. The house, which was used as the hospital, had an L-shaped plan with a large ward in one wing and service rooms in the other. The northern and western elevations were protected by verandas while a room, possibly used by Poutsma as a dispensary, was added at the south-western corner. The ward and the kitchen could be accessed from an eastern verandah. Red Cross flags clearly denoted that the buildings were being used as a hospital. According to Poutsma, the terrain was enclosed by a fence and all entrance doors carried a proclamation signed by De Wet, denying entrance to armed burghers. In terms of the proclamation, attacks on the enemy in the vicinity of the hospital were also forbidden (A155, Vol 176, Statement by Dr Poutsma, p1).

Floor plan of the hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift.

(Compiled with the help of S C du Plessis and C M Smit, 2002).

The attack

At the beginning of January 1902, 3 400 troops commanded by Colonel M F Rimington were implementing the 'scorched earth' policy to the east of the Wilge River. Included in this force was a volunteer unit of Canadian Scouts, comprising 315 men and seventeen officers led by Major C J Ross (Yardley, 1904, p 314). The unit, which was charged with the difficult and dangerous task of reconnaissance, had attracted reckless and impulsive mercenaries into its ranks. Professor C Miller of McGill University, in his study of Canadian units participating in the war, referred to them as 'an unsavoury bunch', scorned by professional soldiers (Oral evidence, Prof Miller to J Lourens,1999).

Rimington's column arrived at the drift on the Wilge River at approximately 08.00 on 9 January 1902. A steep incline on the western side hampered their progress so that they only completed the crossing at 15.00. In the meantime, between 30 and 40 mounted Canadian Scouts under Captain A O Vaughan had embarked on a reconnaissance of the western side of the river. On approaching the hospital, they observed a number of carts driving off at speed in the direction of Reitz. A timely warning from a Boer scout had enabled all patients who were not confined to their beds, to flee. Accompanied by Moll, the medical orderly, they had already progressed beyond reach of the enemy.

The Scouts then launched an attack on the hospital. Poutsma was busy tending the mules while Lily Rautenbach and Van Toorenenbergen were outside observing the approaching soldiers. Van Toorenenbergen had just sent Lily to seek refuge in the building when the Scouts opened fire from the east. At Vaughan's command, a soldier jumped from ris horse and, at a distance of fifteen metres, fired a shot at Poutsma, but missed. 'For God's sake, don't shoot, this is the hospital and I am the doctor', he shouted (A 155, Vol 176, Statement by Poutsma, p 1). The soldier ignored him, firing a second shot which lodged in one of the walls of the building. Vaughan discharged a further six shots at him from his revolver. Poutsma was not hit by any of the bullets, which entered the ward and the kitchen.

On reaching the building, Vaughan and his men, resting their weapons on the window sills, fired into the ward where four patients, who were too ill to flee, were lying on their beds. The patients cried out 'hospital!' and 'Red Cross!'while shards of glass and bullets flew around them. A cloud of dust and cordite fumes filled the air. None of them was injured, although Jan Wessels narrowly escaped death when a bullet hit the wall above his head, showering him with dust. According to Johanna Raubenheimer, at least ten bullets damaged the walls, doors and windows of the ward.

The burst of gunfire sent Lily fleeing towards the door on the northern side of the ward but, before she could reach it, she was struck by several bullets. She momentarily lost consciousness and collapsed betwe1en two beds. On regaining her senses, she experienced acute pain and found that she could not lift her right arm.

Head of the hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift, Hessel Jacob Poutsma

(Source: A B de Pickard, Nasionale Portretboek van Wakers, Leiers, Stryders en Lyers (1916) No 51).

The wounding of Nurse Lily Rautenbach

After the shooting, Vaughan stormed into the ward and instructed two of his men to arrest Poutsma. When told by Van Toorenenbergen that Lily was injured, Poutsma, wresting himself free, went quickly to her aid. He found her lying on the floor in a pool of blood with seven bullet wounds. One bullet had damaged the main artery in her neck causing intense pain and severe bleeding. Poutsma staunched the bleeding before bandaging her wounds. However, the badly traumatised Lily fainted again. When she regained consciousness, two British doctors were standing next to her bed. They had brought brandy and bandages to supplement the hospital's diminishing supply.

Vaughan, on seeing Lily, asked her, in the presence of Johanna Raubenheimer, through which window she had been shot. When she showed him, he immediately appealed to her not to blame his men because it was he who had fired through that specific window. He expressed his regret, suggesting that she come to the British column where she would receive better medical treatment. Lily rejected the offer. Although weak and seriously injured, she appreciated that Vaughan was sincere and assured him that she bore him no grudge. She accepted that he had not intended to shoot her, but that his gunfire had struck her as she fled. Vaughan, deeply affected by Lily's attitude, exclaimed: 'My God, I could never say that!' (Hobhouse, 1924, p 144). Lily later explained that she had thought that she was dying and that, as a Christian, she did not want to die with bitterness in her heart.

The Head Nurse at Bezuidenhout's Drift hospital, Louisa Susan (Lily) Rautenbach,

20 August 1876 - 28 September 1971. (Photo: by courtesy L G von Zeil).

Responding to Vaughan's offer of assistance, the injured Lily Rautenbach requested that he inform her mother of the incident without unnecessarily alarming her. Vaughan complied twice with this request, once shortly after the shooting, and again later when he had ascertained that she was recovering. Lily implored Vaughan not to take Jan Wessels prisoner because of the seriousness of his injuries. She also asked him not to confiscate the two cows which provided milk for the hospital. Wessels was allowed to remain, but the cows were driven away. Vaughan provided Lily with a supply of sugar, salt, lime juice, candles and bandages.

An act of revenge?

Rimington himself arrived at the hospital later in the day to sympathize with Lily. He observed that he would not have minded if Poutsma had been killed, since a British doctor had been killed by the Boers. His response is reminiscent of that of Vaughan, who, shortly after he had fired the volley of shots at Poutsma, had thrust his revolver under the doctor's nose and shouted: 'I am darned sorry that I didn't succeed in shooting you' (Hobhouse, 1924, pp 1425). Both were reacting to the news of the death of a civilian doctor, Doctor G F Reid, fifteen days previously at Groenkop. Yet, evidence of the incident indicates that Reid's death had been an accident. (Contrary to international codes of practice, the hospital at Groenkop had been placed close to the British camp, so that when De Wet attacked the camp on Christmas Day 1901, it had been in the burghers' line of fire.)

Rimington's argument that the British were not aware of a hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift must be rejected. Not only was the building clearly identified with Red Cross flags, but, during the attack, Poutsma and the patients had uttered warning cries. Furthermore, a sworn statement made by Johanna Susanna de Jager of the farm Slabbert's Hoek, on the eastern bank of the river, on 14 January 1902, before the Assistant Chief Commandant of the Harrismith and Vrede Division, showed that the British knew the precise location of the hospital. In her statement, the witness reveals how, shortly before the attack on the hospital on Thursday 9 January, Rimington's troops had plundered her house, taking food and clothing. One of the officers had enquired about a hospital in the vicinity. She had informed him that the hospital was just west of the river on the farm Bezuidenhout's Drift. She had also been asked what type of a man the doctor was, a further indication of their interest in Poutsma (A 155, Vol 176, Sworn Statement, 14 January 1902 ).

The death of Dr Reid and 67 British troops at Groenkop had aroused strong feelings of resentment among the British forces. De Wet had attacked at a time when they had felt that they were in control of the military situation, and that the war would soon be over and they would be able to return to their homeland. The attack on Bezuidenhout's Drift was an expression of their anger and frustration.

Immediately after the attack on the Boer hospital, Poutsma sent a report signed by Van Toorenenbergen, Johanna Raubenheimer and Johanna Scheepers to General de Wet. President Steyn and the general hastened to Bezuidenhout's Drift. The President, highly indignant about the incident, forwarded Poutsma's report, together with sworn statements and a strongly worded letter, to Lord Kitchener in protest. Johannes Theron, Secretary of the Free State Executive Council, who helped to compile the affidavits, related 36 years later that Kitchener's response included sworn statements by British troops dismissing the allegations as lies (A G von Zeil Collection, Die Volksblad, 1938). Kitchener added: 'The statements you forward from Dr Poutsma are so manifestly untrue that I do not consider it necessary to discuss the matter' (A 155, Vol 176, Kitchener - Sir, 5 February 1902).

With his arrogant, disdainful attitude, Kitchener hoped to distract attention from the disregard shown by Rimington's force for internationally recognised regulations governing hospitals during conflict situations. Some of his subordinates were critical of this approach. Dr Miller, a medical doctor with Rimington's column, declared his willingness to defend Poutsma's contentions (A 155, Vol 176, Statement by Dr Poutsma, p 1), while Col Nixon, who passed the scene of the attack six weeks later, described the incident as a blot on the good name of the British Army and demanded that Vaughan be shot (A G von Zeil Collection, Die Volksblad, 1938).

After the War

Lily remained in the hospital at Bezuidenhout's Drift until the end of the war, when her family took her to Fouriesburg. With the assistance of the Magistrate of Winburg, she obtained permission to travel to Bloemfontein, where she was admitted to the National Hospital on 8 September 1902. Dr D T Tomory carried out two operations to remove pieces of lead from her paralyzed right arm and shoulder. With additional physiotherapy, her condition improved considerably, although she never regained the full use of her right arm and hand (Hobhouse, 1924, pp 144-5).

After Lily and her fiance were married in March 1903, her husband made an earnest attempt to secure a pension for her from the British Government. He wrote three times to Capt Vaughan without receiving a reply and even approached Emily Hobhouse for help. Altogether, Hobhouse sent Lily an amount of £40, but could not obtain assistance from the British Government and even her appeals to the British public failed (A155, Vol 176, Emily Hobhouse to Mrs Boshoff, 16 March 1905).

Lily did not allow her handicap to influence her life adversely. She brought up ten children, managed her own farm and found time for community work. She became the only woman to be awarded the War Medal of the South African Republic (A G von Zeil Collection, L S Boshoff to Adjutant-General, 15 July 1954 ).

Conclusion

The most striking message ensuing from this incident is to be found in Nurse Lily Rautenbach's attitude towards her attacker. When Capt Vaughan, who had caused her great pain and suffering, accepted responsibility for his action, she responded with a conciliatory gesture. For Lily, the next seven years were a relentless struggle to reconcile herself to her disability. Although her conduct was marked by courage and patriotism, it is her forgiveness of the enemy for a deed which drastically altered her life, that provides us with a valuable message which, a hundred years later, is still relevant and significant.

Acknowledgements

The writer's thanks are due to Glenn von Zeil, Lily Rautenbach's great grandson, who willingly shared his knowledge with her and to Loffie Cronje for allowing her access to the farmstead where the incident took place. She also extends her appreciation to J A J Lourens for preparing the illustrations and proofreading the article.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archival sources

FREE STATE ARCHIVES (VAB): War Museum Collection, A155, Vol 176, No 1; Statement by Dr Poutsma (translated from German) no place, no date; Sworn Statement by Johanna Susanna Sophia de Jager, no place, 14 January 1902, Kitchener, Sir, Pretoria, 5 February 1902.

TRANSVAAL ARCHIVES (TAB): A Wypkema Collection, W223, PAl, No 1, Provost Marshal - M Charlier, Acting Consul-General for the Netherlands, Pretoria, 26 April 1902; List of Patients.

Personal Collections: Lourens, J, Correspondence with Prof J C de Villiers, 23 July 1998; Von Zeil A G, 'Britse skending van die Rooi Kruis,1938' in Die Volksblad; correspondence, L S Boshoff to Adjutant-General, Pretoria, 15 July 1954; and correspondence, Emily Hobhouse to Mrs Boshoff, Philippolis, 16 March 1905.

Personal Interviews:

Crots, Elsabe, daughter of Lily Rautenbach, Munster,1998.

Du Plessis, Casper and Steyn, Petrus, 2001, born at Bezuidenhout's Drift and lived there from 1926 to 1950.

Miller, Prof C, telephonic interview, 1999.

Smit, Chris, Lindley, 1999. His great grandfather purchased Bezuidenhout's Drift in 1917.

Publications

Andriessen, W F, Gedenkboek van den Oorlog in Zuid-Afrika (Amsterdam, 1904).

De Kock, W J, (ed) Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek, Deell (Cape Town, 1972).

Hobhouse, E, (ed) War Without Glamour or Women's War Experiences Written by Themselves, 1899-1902 (Bloemfontein, 1924).

Kestell, J D, Through Shot and Flame (Johannesburg, 1976).

Odendaal, S J, 'Mediese Rol van doktor A E W Ramsbottom voor, tydens en onmiddellik na die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die OVS' (MA thesis, UOFS, 1979).

Pakenham, T, The Boer War (Jeppestown, 1997).

Yardley, J Watkins, With the Inniskilling Dragoons, The Record of a Cavalry Regiment during the Boer War, 1899-1902 (London, 1904).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org