The South African

The South African

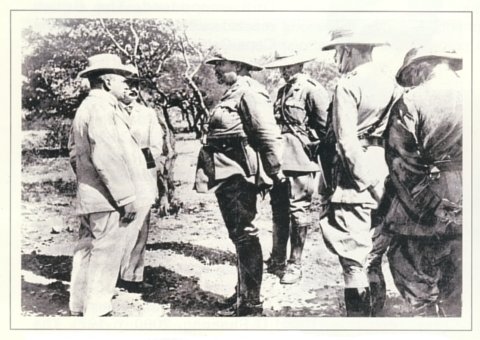

General J C Smuts in East Africa observing the departure of German trains.

(Photo: Ditsong National Museum of Military History, Saxonwold, Johannesburgt).

Introduction

It is as a statesman and philosopher that Field-Marshal Jan Christian Smuts is mostly remembered. Others would describe him as a politician. He saw himself as being a general in his spare time (Hancock, 1962, p 107). However, few have tried to assess the competence of this part-time general. Importantly, Louis Botha, J C Smuts and J L van Deventer were the only South Africans to be commanders-inchief in a theatre of operations in either of the two world wars.

Smuts's reputation as a general in the East African Campaign of the First World War is not good. Some of the criticism comes from the revelations by his erstwhile opponent, Generalmajor Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who managed to evade capture for the duration of the War, but most of it stems from the diaries of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, the Chief British Intelligence Officer in East Africa during Smuts's tenure as commander-in-chief. Meinertzhagen critically describes the failure of manoeuvre after manoeuvre. These criticisms were seized upon and used by Charles Miller in his highly readable Battle for the Bundu. Even W K Hancock, Smuts's principal biographer, regarded Meinertzhagen as an excellent source (Hancock, 1962, p 412). However, the recent publication of a book by Brian Garfield, The Meinertzhagen Mystery - The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud (Potomac, Washington DC, 2007) has thrown doubt on the credibility of the good colonel's diaries, revealing that they were typed up some time after the events that they purport to describe and that they were seriously flawed. By examining Meinertzhagen's pre-war activities in Kenya and his own wartime accounts, Garfield shows that, far from being a reliable witness, Meinertzhagen was an unscrupulous fabricator of myths. As a result of the unmasking of one of his principal critics now, as we approach the centenary of the First World War in the post-Apartheid era, it is perhaps time to reassess one of South Africa's most significant figures in that war. After all, Smuts was the first South African to command a major Imperial force. Furthermore, in a world which has seen the successful waging of war by men and women who were not professional soldiers, the evaluation of a man who was, by his own admission, a general in his spare time, is a reasonable, if not essential, process. (Hancock, 1962, Volume I, p 107).

Early life

Smuts's first experience of military life was as a volunteer in the Victoria College Volunteer Rifle Corps, which he joined at the beginning of his second year at Stellenbosch. As such, he would have worn a British red coat uniform. The volunteers would have taught Smuts close order drill and allowed some shooting at government expense. So Smuts had more than a passing acquaintance with the basics of military matters. However, none of his biographers reveal if Smuts passed beyond the rank of private. Interestingly, the mounted infantry detachment of the Victoria College Volunteer Rifle Corps joined the South African Light Horse en masse and fought for the British Empire during the Anglo-Boer War.

Smuts was a voracious reader and his interests were wide ranging, yet none of his biographers have mentioned works of military history that had a profound influence on him. Thomas Pakenham has no doubt that Smuts had an extensive knowledge of military history (Pakenham, 1979, p 472). A plan which Smuts devised for the Boer Republics in 1899 (Hancock, 1962, Volume 1, pp 313-29) is solid proof of the depth of this knowledge. Although the plan was never put into practice owing to the intervention of President Steyn (Hancock, 1962, pp 107-112; Pakenham, 1979, p 102) it nevertheless shows that Smuts had a firm grasp of strategic principles and could formulate a logical and effective plan of action.

From the outbreak of the South African (Anglo-Boer) War in October 1899 until the fall of Pretoria in June 1900, Smuts was mainly occupied with his duties as State Attorney. Then, after the battle of Diamond Hill (11-12 June 1900), he added to this the duties of political commissar, chief of staff and second-in-command to General J H (Koos) de la Rey. In these capacities, he attended the conference of the Republican commanders at Cypherfontein (October 1900), where the decision was taken to fight a guerrilla war and to invade the Cape Colony. This decision may have been informed in part by Smuts's knowledge about the partisan (guerrilla) war in the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War (1861-5) (Hancock, 1962, pp 122-3; Pakenham , 1979, P 470-2), but to what extent had the Republican leadership considered the consequences of their strategy? Guerrilla wars are ugly conflicts but in the context of guerrilla wars, the decision to invade the Cape Colony was sound strategy. It would open up a new front and stretch the finite British resources.

Interestingly, when General Giap opened a new front in Laos in the First Indo-China War (1945-54), this was hailed as an act of considerable generalship. Yet historians have largely withheld the same accolade from the Boer command. It is noteworthy that, where Christiaan de Wet had tried and failed, Smuts had succeeded. What went into making this stunning success for a learner commander? The tutelage of De la Rey certainly played its part, as did Smuts's intellectual forays into the art of war.

Apprenticeship

Smuts continued his study of the art of war under the guidance of Koos de la Rey. He gained practical experience of the problems of command as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the Republican commandos at the battle of Nooitgedacht (13 December 1900). Here, General de la Rey defeated Major General Clements's column by exploiting the mistakes that Clements made in deploying his men in unfamiliar terrain. Nooitgedacht proved fertile ground for teaching a learner commander. The aftermath of the battle saw Clements making good his escape largely due to his own exertions and the inability of the Republican commandos to follow up on a successful assault.

When Smuts began his invasion of the Cape Colony, the journey to the border was, in itself, a major achievement. Both in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, British columns had to be eluded. A little less alertness by Smuts's men or a little more energy and watchfulness on the part of the British and the expedition would have ended before it had started. Luck attended Smuts during the crossing of the Orange River. The drift which he planned to use had been guarded by a British column, but Lord Kitchener, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, South Africa, had sent it to chase a shadow. This allowed Smuts's commando to cross Kiba Drift unopposed. The British reacted swiftly. A chase through the Cape Colony followed. Yet Smuts and his men were still at large when the forces of the Boer Republics surrendered on 31 May 1902.

It is important to note that, according the official history of the Anglo-Boer War, in January 1902 Smuts had about 13 000 men under his command in the northern Cape (M H Grant, 1910, p 453). The ravages of war reduced this number and 2 035 men made the initial surrenders at Clanwilliam, Britstown, Cradock and Hopetown. Some 287 of Smuts's Transvalers survived his epic ride (T and D Shearing, 2000, p 197). The importance of these numbers will become clearer later when considering General Smith-Dorrien's comments on Smuts's fitness for command. (Smith-Dorrien was to have commanded the British forces in the German East Africa campaign in the First World War).

Peace

After the Anglo-Boer War, Smuts briefly returned to practising as an advocate and together with Louis Botha formed Het Volk, in preparation for the day that the Transvaal Colony was granted responsible government, which would make it autonomous with respect to its internal affairs. This occurred in 1906 and Het Volk won the election held in February 1907.

This placed Smuts in control of the Transvaal Volunteer Force, which he promptly reduced in size on the grounds of economy. Nevertheless, it was a fair-sized force, consisting of three mounted rifle regiments (the Imperial Light Horse, the Northern Rifles and the Southern Rifles), three infantry units (the Transvaal Scottish, the Witwatersrand Rifles, the Rand Light Infantry), an artillery battery (Transvaal Horse Artillery) and a railway/engineer unit (the Central South African Railways Volunteers). Very few British regular officers administered a force this size in peace-time. Although much of the work was done by the permanent staff, Smuts would have gained considerable experience in running a peace-time military organisation. Much of this experience was applicable in war-time conditions.

Formation of the Union Defence Forces (UDF)

The formation of the Union of South Africa broadened Smuts's responsibilities. He was now Minister of Defence for the whole Union. Most importantly, he had the responsibility of amalgamating the various military forces of the four former colonies. The Cape and Natal had converted their part-time forces from volunteers into militia in the early part of the twentieth century, whereas the Transvaal had only volunteers with a small permanent headquarters cadre and provided adjutants and regimental sergeantsmajor to its units. The Cape had a permanent regiment in the form of the Cape Mounted Riflemen and its attached artillery battery together with a permanent Coldnial Forces staff. In Natal, apart from the staff at militia headquarters, the only full-time personnel were some regimental sergeants-major and the district staff officers. Natal also had a militia reserve organisation. The Orange Free State had no military units or infrastructure.

The spare time general in the 1930s:

J C Smuts, in civilian clothing waits to give a speech.

In addition to the above, there was the very strong commando tradition of the former Boer republics. This tradition had also been resurrected in the Cape Colony during the Anglo-Boer War in the form of District Mounted Troops. In the Union Defence Act of 1912, Smuts drew on South African military traditions as well as the defence legislation of Great Britain and the Dominions of Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The 1912 Act is remarkably similar to these defence acts of the other dominions.

The act made provision for a Permanent Force consisting of an Instructional and Administrative Staff together with five regiments of mounted riflemen, each with an attached artillery battery and small medical, ordnance and supply cadres. In addition, there was to be a Coast Garrison Force to man the defences of Cape Town and Durban. The main source of manpower was the Active Citizen Force, which was an amalgamation of the militias and volunteer forces of the old colonial forces, together with many new units (G Tylden,1954, pp198-9). The commandos were recreated in the form of Defence Rifle Associations.

Smuts's creation was put to three severe tests within two years of the passage of the Defence Act. The first was the 1913/14 industrial action in which the new Union Defence Forces were successfully used. Then came the 1914 Rebellion in response to the Government's decision to invade German South West Africa in the First World War. Mounted and dismounted rifle regiments were merged with Defence Rifle Associations to form government commandos which played a major role in ending the rebellion.

The real test of Smuts's creation was the German South West Africa campaign. Although numerically small, the German South West Africa Schutztruppe and its associated reservists and police were well trained with considerable terrain advantages and a railway network which allowed the use of an interior lines strategy. Yet, apart from the elimination of the South African Mounted Riflemen force at Sandfontein at the start of the campaign, the new Union Defence Forces outmanoeuvred their German opponents throughout the campaign. It cost South Africa 266 deaths, of which 88 were from enemy action. It was a superb performance by any objective standard and should at least allow Smuts consideration for membership of the club of great organisers of victory.

One of the finest commanders of mounted riflemen in the world:

General Louis Botha (centre), accepts the surrender of Windhuk,

German South West Africa, 10 May 1915. (Photo: DNMMH).

German East Africa

By contrast, the British campaign in German East Africa was going badly. The German East Africa Schutztruppe, under the command of Paul von LettowVorbeck, had seized the Taveta Gap and repulsed Force B, which had been despatched from India, at Tanga. The British commanders then went from reverse to reverse and it was decided that one of the more competent commanders in the British Army, Lieutenant General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, would take command in East Africa. However, he caught pneumonia and was declared unfit. At this point, General Smuts was chosen to replace him. Ross Anderson, the author of Forgotten Front 1914-1918, makes severe criticisms of Smuts as a general and he bases this on a semi-official letter which states that Smuts had commanded only 300 men in the Anglo-Boer War (R Anderson, 2007, pp 110-11, 325). By contrast, as indicated above, the official British history credits Smuts with nearly 13 000 men in January 1902 and he was controlling operations over a large area of the Cape Colony. When his men surrendered in May 1902, they numbered 2 035 and more surrendered later. This is a force several hundred percent more than a mere 300.

This brings us to a key issue, the professionalism of the British regular officer. The British Army drew most of its officers from what was loosely called the gentry. The gentry were in fact a heterogeneous group which ranged from dukes to men who had little private means but whose ancestors had served as officers in the British Army for several generations. From 1850 several processes were underway which would have a major impact on the competence of the British officer. In 1850 scientific pursuits were regarded as natural for a gentleman but, by the end of the century, this was no longer the case (T Jeal, 1989, p 4). More serious was the cult of amateurism, driven by the British public school system, aggravated by the emphasis on what was termed 'character' as opposed to 'intellect' (intelligence). Indeed, intellect was believed to go hand in hand with social and physical incompetence (G Harries-Jenkins, 1977, p 104).

It seems that General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien doubted Smuts's competence for high command (R Anderson 2007, p 325). Yet, he must have been aware that few men in the British Army had any experience of high command. Aldershot was the only station where an army corps of two divisions was kept assembled in peace-time. The peace-time manoeuvres pitted one army corps against another. In addition, East Africa had command responsibilities above those of an army corps. Smith-Dorrien was one of only a handful of British soldiers who had been in commahd of a corps. No serving British soldier had had a major theatre command since the Anglo-Boer War. Thus, the perceived lack of experience in high command is, in a sense, irrelevant, as such experience was not available to the British Empire in 1914.

One of Smuts's weaknesses was a tendency to overlook details (Phillip Weyers, Smuts's grandson, in conversation). This could be a serious failing, especially with respect to logistics, where details are of vital importance. However, most successful British armies usually required a commander to listen to a competent logistics specialist. The logistic problem:; in East Africa can be traced to two main causes. Firstly, in contrast to the German Schutztruppe, whose logistics set-up already existed, the British had to start almost from scratch. Secondly, the British forces came from India and a pernicious parsimony dominated the logistics of operations mounted from India (A J Barker, 1967, p 123). One effect of this was that quinine sulphate was issued when available, rather than the more effective and palatable quinine hydrochloride (A C Martin, 1969, p 290). The differences in effectiveness of their respective logistics systems also had the result that the German forces were more mobile than the British. Given these logistical dilemmas, any British commander would have laboured under the same difficulties.

When Smuts arrived in East Africa, he already had several strikes against him. He was a colonial officer and a former enemy. Furthermore, he was a politician and, even worse from the point of view of the regular British officer of the British and Indian armies, he had intellect. His score of a double-first at Cambridge drew deep suspicion rather than admiration. Most historians have accepted the view of Smuts held by regular British officers without questioning the perspective that formed that viewpoint. In a very real sense, they represented utterly different world views.

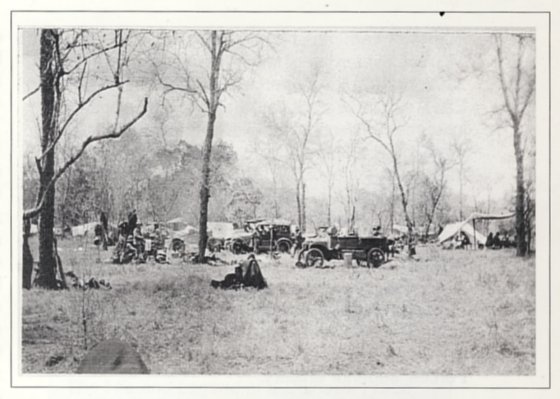

General Jan Christian Smuts's camp near Ngeringeri River.

(Photo: Ditsong National Museum of Military History).

German East Africa Schutztruppe

While the British regular officers' view of Smuts has been accepted uncritically, the combat effectiveness of the German East Africa Schutztruppe has not been fully explored. The key lay in the fact that the Schutztruppe field company was an independent entity with its own logistic support. As such, it was incredibly mobile in East African conditions. This field company consisted of 160 askaris in peace-time and 200 in wartime, with a leadership cadre of between sixteen and twenty German officers and NCOs, which included a medical doctor. The logistic support came from 433 carriers. Notably, the field company had two (sometimes three) Maxim machine-guns (P Abbot, 2002, pp 6-7; R Anderson, 2007, p 26). The German East Africa Schutztruppe was a very flexible instrument with considerable firepower. This firepower more than compensated for the obsolete Model 1871 rifles in the hands of most of the Schutztruppe's askaris. Such firepower could delay or even stop a battalion in its tracks. The power of the Schutztruppe field company was enhanced by the nature of the East African terrain. Open spaces were interspersed by large tracts of impenetrable bush, which had the effect of channelling an advance along easily predictable lines. The Schutztruppe's skill in camouflage went a long way towards countering [British] East Africa Forces' superior artillery.

The situation in East Africa

The war in East Africa had begun disastrously for the British. The landing at Tanga had been repulsed with ease. This was sufficient to deter further amphibious operations, in spite of the success of such operations in South West Africa. It should be recognised, however, that both the Luderitzbucht and Swakopmund landings were unopposed and that the greatest amphibious operation of the First World War, at Gallipoli, had ended in evacuation by the time Smuts assumed command in East Africa. All these factors served to create a climate in which proposals for amphibious operations would not be considered.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck's offensive had broken through the Taveta Gap between the slopes of Kilimanjaro and the North Pare Mountains. The Schutztruppe were dug in on Salaita Hill. Major-General Michael Tighe, hoping to score a success before Smuts arrived, attacked Salaita Hill. This attack was repulsed, but it should be noted that the regular British officers had not anticipated that the Germans would duplicate General de la Rey's Boer War tactic, used at Magersfontein in South Africa in December 1899, of placing the trenches at the foot of the hill. Furthermore, neither British intelligence nor reconnaissance had been able to detect this deployment before the battle at Salaita Hill. The chief of East Africa Force's intelligence department was none other than Richard Meinertzhagen, who makes no mention of Salaita Hill in his memoirs.

Smuts's first task was to eject the German forces from the Taveta Gap and trap the Schutztruppe. To do this, he proposed a frontal advance combined with a short outflanking move along the slopes of Kilimanjaro to the German rear by Van Deventer's 1 st South African Mounted Brigade. Some days before, General Stewart had started a long outflanking move which began at Longido, north of Kilimanjaro. The target of this operation was Moshi, deep in the German rear.

Had the Germans held their positions, they would have been trapped where they were. If they retreated, the manoeuvre would force them into positions not of their own choice. The Germans decided to retreat. The South Africans caught up with them at the Latema-Reata Nek. Here, General Tighe ordered an attack. The same desire for success which had precipitated the attack on Salaita Hill now brought about the assault on the Latema-Reata Nek. Like so many military operations, this one almost succeeded. However, the night brought confusion and orders to withdraw were issued. Tighe wanted to renew the attack, but Smuts called it off in the expectation that Van Deventer's outflanking march would force the Germans to withdraw. This willingness to call off an attack places Smuts in a special class of generals. Very few generals have the moral courage to call off an attack. The temptation always exists to hope that another, and perhaps even yet another, attack will succeed. The horrendous casualties on the Western Front were a direct result of this combination of wishful thinking and moral cowardice.

When dawn broke, it found the South and East African troops still contesting the heights above the nek. Smuts showed his decisiveness when he ordered fresh troops to be rushed up to the nek. Once beyond the nek, Smuts drove on to Moshi to find that General Stewart had not arrived and that Von Lettow-Vorbeck had escaped. Although there have been many attempts to excuse Stewart's tardy advance, this writer feels that it can be ascribed to a feeling of superiority that the German general had attained over his regular British officer adversary, causing Stewart to suffer an anxiety attack. The rains then set in, bringing operations to a halt.

At this point, Smuts resolved to go against conventional thinking and launch a major operation in the rainy season, acting on incorrect information by fellow Afrikaners that the rainy season was less intense further south. The key to the new offensive was a drive on Kondoa Irangi, which would throw the Schutztruppe off balance and allow the rest of the British force to advance down the Pangani Valley. The operation succeeded in its aim of drawing Von Lettow-Vorbeck to Kondoa Irangi like a moth to a flame. After the rains ceased in June, there was a delay of some weeks before Van Deventer could continue his advance to the Central Railway in support of the operation. The advance down the Pangani River proceeded smoothly and Dar-es-Salaam finally fell on 4 September 1916.

In January 1917, Smuts left Africa for London to take up a post in the British War Cabinet. Henceforth, he would be concerned with grand strategy. He had taken East Africa Force from inside Kenya to the Central Railway inside German East Africa with very few battle casualties. British Imperial officers, with their taste for frontal attacks, may have been able to achieve similar results, but the battle casualties would probably have come close to matching those from disease.

Assessment of a general

There persists a belief that that Smuts could have done better and a regular British officer would have done so. Yet, before Smuts's arrival in East Africa, the record of regular officers there had been abysmal. They had gone from overweening arrogance to mindnumbing admiration. The true commentary on General Stewart's generalship, having lost the only real chance of catching the German East African Schutztruppe, was a damning reassignment - he was given the safe but out-of-the-way command of Aden.

The British had to build their logistic apparatus and organise their medical services - from scratch in East Africa, where the terrain and climate created challenges for which neither British logistic expertise nor medical science were prepared. The regular British officer was also unprepared for a war against a professional opponent, waged with dominion troops and commanded by a brilliant, but intellectually arrogant university graduate.

Smuts should not be judged too harshly for his failure to catch the highly mobile Schutztruppe in the unfamiliar East African terrain, as this would have been a difficult challenge for any British commander. It should not be a slur on his generalship. The role of machine-guns, with which the Schutztruppe was lavishly supplied, should also be appreciated in making an assessment of Smuts's decision to use outflanking manoeuvres rather than frontal attacks. The latter may have been successful, but only with severe losses.

Smuts's preference for using outflanking moves to attempt to trap the enemy was the right solution. This strategy had worked well in the arid or desert conditions of German South West Africa, where the Germans, like most western troops, had shown a tendency to retreat when their lines of communication were threatened.

Smuts's concern to avoid casualties was unusual in a First World War commander. Yet, what historians have condemned on the Western Front in Europe has become, by a curious mutation, acceptable in East Africa. Casualties on one side are a measure of the other side's success. They are not a measure of a commander's determination or even that of the troops. Smuts's mistakes were arrogance and a premature announcement of victory, but not of generalship.

This writer believes that the final verdict on this part-time general is that, while he may not have been as good as the Australian Sir John Monash, he was certainly competent in the context of the First World War.

General J C Smuts in British Army uniform in the 1940s.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbott, P, Armies in East Africa 1914-1918 (Osprey, Oxford, 2002).

Anderson, R, The Forgotten Front 1914-1918 (Tempus Publishing, Stroud, 2007).

Barker, A J, The Neglected War, Mesopotamia 1914-1918 (Faber and Faber, 1967).

Duffy, C, Siege Warfare, The Fortress in the Early Modem World (Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1979).

Garfield, B, The Meinertzhagen Mystery, The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud (Potomac, Washington DC, 2007).

Grant, M H, The History of the War in South Africa, Volume IV (Hurst & Blackett, London, 1910).

Harries-Jenkins, G, The Army in Victorian Society (Routledge, Kegan, 1977).

Hulme, J J, 'Gallant Gentlemen, 1855-1865' in Military History Journal, Volume 2 No 1, June 1971, pp 30-7.

Jeal, T, Baden-Powell (Century Hutchinson, London, 1989).

Leslie, E E, The Devil knows how to ride, The true story of William Clarke Quantrill and his Confederate Raiders (Da Capo Press, 1998).

Martin, A C, The Durban Ught Infantry, Volume I, 1854-1934 (HQ Board, Durban Light Infantry, Durban, 1969).

Miller, C, Battle for the Bundu (MacMillan, London, 1974).

Paice, E, Tip and Run, The untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 2007).

Pakenham, T, The Boer War (Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg, 1979).

Shearing, T and D, General Smuts and his Long Ride (privately published, Sedgefield, 2000).

Smithers, A J, The Man who disobeyed, Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and his enemies (Leo Cooper, London, 1970).

Tylden, G, Armed Forces of South Africa (1954, reprinted Trophy Press, 1980).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org