The South African

The South African

Many South Africans were enthusiastic about serving in the Second World War. As a result, a number of South Africans were absorbed into British military structures and were not part of the Union Defence Forces. This article is about seven notable South Africans who served in the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the war.

MARMADUKE THOMAS ST JOHN 'PAT' PATTLE was born in Butterworth in the Eastern Cape in 1913. He was from a family with a military background and decided on a military career as soon as he had completed his education at Graemian College in Grahamstown. His attempts to become a pilot in the South African Air Force were unsuccessful and, after working for a period in the mining industry, he found his way to the United Kingdom, where he joined the Royal Air Force. He excelled in flying, aerobatics and marksmanship, and completed his training in 1937, with honours. He was then posted to 80 Squadron which moved to the Middle East a year later.

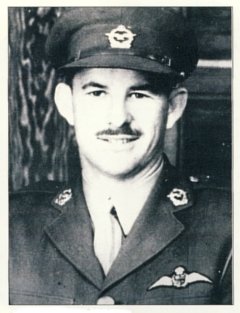

Squadron Leader 'Pat' Pattle

(Photo: Courtesy, Ditsong National Museum of Military History, Saxonwold, Johannesburg).

By the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Pattle had risen to the rank of flight lieutenant. He soon earned a reputation for initiative and efficiency and formulated many theories regarding air combat. So successful were these theories in practice that he soon became the ace pilot of his squadron. The Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters with which the squadron was equipped were out of date compared with the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane monoplanes used by Fighter Command in the United Kingdom. Yet these aircraft were flown with such skill by the pilots of 80 Squadron that they became more than a match for the faster Messerschmitts, Fiats and Reggianes of the German and Italian air forces.

A Gloster Gladiator as flown by No 80 Squadron, RAF,

at the time of the outbreak of the Second World War (Photo: Ditsong: NMMH).

Eighty Squadron was initially successful in operations against the enemy, but soon hit a low, when a number of pilots, including Pattle, were declared missing. On 4 August 1940, whilst his flight was escorting a Westland Lysander on reconnaissance, a formation of seventeen Fiat CR 42s and ten Breda Ba 65s appeared. Pattle shot down one of each type, but was also hit and forced to bale out and parachute behind enemy lines. He immediately set out for British lines on foot, narrowly escaping capture by German patrols. He was eventually picked up 24 hours later by a British patrol and some hours later was back with 80 Squadron.

His successes against German and Italian aircraft continued after 80 Squadron was sent to Greece. In January 1941, the Squadron was split into two separate units, Pattle leading one of them. He celebrated this move by shooting down three enemy aircraft in one day, the first of many triple victories which brought his personal total to thirteen enemy aircraft. For this, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), one of the first decorations to be won by the RAF in the Greek Campaign. He was considered a phenomenal shot and a clever tactician, always picking the right moment to attack.

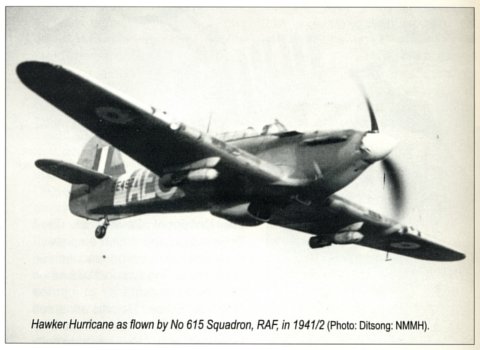

In February 1941, 80 Squadron was equipped with Hawker Hurricane aircraft. These were sent into action for the first time when Pattle's flight escorted thirty Bristol Blenheim bombers on a mission in Greece. The bombers were attacked by a squadron of Fiat G 50s, who lost four of their aircraft to the Hurricanes in a matter of minutes. Pattle was credited with shooting down the leader of the Italian squadron. Soon, Pattle's personal total had risen to 23 and he was awarded a bar to his DFC. Promotion to squadron leader soon followed and by April 1941 he had been appointed to command 33 Squadron, which was equipped with Hurricanes and based at Larissa. He commanded the squadron with skill, despite losses against superior numbers of German and Italian fighters. On average, the squadron scored five enemy aircraft for every Hurricane it lost.

As there were no replacement aircraft or pilots available, the number of Hurricanes was reduced to a mere fifteen operational aircraft by 20 April. These were gathered together to intercept a wave of German dive bombers and escort fighters which were heading for Athens. It was Pattle's last and greatest action. He destroyed two Messerschmitt Me 11 Os and an Me 109 before swinging around to assist a Hurricane which was being pursued by an Me 110. In attacking the aircraft, he left his own rear uncovered and was shot down and killed by two Me 110s, his own aircraft plunging into Eleusis Bay.

Pattle's final tally of enemy aircraft exceeded forty. Some survivors of the Greek campaign claim that it may even have been as high as 60. He was the highest scoring pilot of the Royal Air Force and indeed of all the Commonwealth air forces and his medals are on display at the Ditsong: National Museum of Military History in Saxonwold, Johannesburg.

ADOLPH GYSBERT 'SAILOR' MALAN was born in Wellington in the Western Cape in 1910. At an early age, he decided on a career at sea. After serving aboard the training ship, General Botha, he joined the Union Castle Steamship Company and attained officer rank. The urge to fly soon took over and in 1935 he wrote a letter which led to his acceptance in the Royal Air Force. After gaining his wings, he was posted to 74 Squadron based at Biggin Hill, which flew Gloster Gauntlet aircraft. He earned the nickname 'Sailor'.

Group Captain 'Sailor' Malan and his pet dog

(Photo: Courtesy, Ditsong: NMMH).

In 1938, Malan's flight won the Sir Phillip Sassoon Trophy for fighter combat tactics. In the same year, 74 Squadron was re-equipped with the new Supermarine Spitfire aircraft. The squadron underwent extensive combat training after the outbreak of the Second World War. After the Low Countries had been overrun by the Germans in April and May 1940, 74 Squadron was ordered to patrol over the English Channel and along the French coast. They soon came into contact with the Luftwaffe, Malan succeeding in destroying a Junkers Ju 88 and a Heinkel He 111 on one day, and claiming another Ju 88 on the next day. More notable successes followed, but his own aircraft was hit and damaged.

After a week of continuous action over and around Dunkirk, Malan and his fellow pilots were in need of rest. The squadron was withdrawn from operations, having destroyed thirty German aircraft in seven days for the loss of three of their own aircraft and pilots. Malan's share of the spoils was five aircraft and led to the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) at the end of May.

For the remainder of June 1940, 74 Squadron focussed its activities on intercepting enemy night raiders. Here, Malan achieved the distinction of becoming the first RAF pilot to destroy two German bombers in one night. Then, during the first phase of the Battle of Britain, Malan added an He 111, two Dornier Do 178 and an Me 109 to his total. The result was the award of a Bar to his DFC, with an official citation that commented on ' ... his magnificent leadership, skill and courage which have been largely responsible for the many successes obtained by his squadron'.

In August 1940, Malan became a squadron leader and was appointed to command 74 Squadron. During the month, he accounted for four enemy aircraft destroyed and four damaged. Thereafter, the Squadron was sent to Kirton-on-Lindsay for rest, re-equipping and training new pilots. It was here that Malan compiled his Ten Rules for Air Fighting which later became famous throughout Fighter Command after the Air Ministry had them printed on posters and displayed in every fighter station.

In October 1940, Malan brought his squadron back to Biggin Hill, the most bombed aerodrome in Fighter Command. By the end of November that year, 74 Squadron had destroyed over eighty German aircraft, Malan claiming eighteen of these. Soon afterwards, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for ' ... commanding his squadron with outstanding success over an extensive period of operations, and by his brilliant leadership, skill and determination [that] has contributed largely to the success achieved.'

Early in 1941, Malan's squadron became part of the Biggin Hill Spitfire Wing which took part in sweeps over northern France in an effort to bring the Luftwaffe to battle. During one of these sweeps he scored his 20th kill by destroying an Me 109. In May, he was promoted to Wing Commander and appointed commander of the Biggin Hill Wing, which included 92 and 609 Squadrons. He celebrated this promotion by doubling his score of victories. In June, he shot down nine Me 109s, sustaining wounds to his wrist and thigh and damage to the wings and cockpit of his Spitfire. He was soon back in action and in July his total reached 32 aircraft destroyed, an RAF record which would stand for almost three years. He was awarded a Bar to his DSO.

In October 1941, Malan gave a series of lectures in the United States of America and made a tour of Army Air Corps squadrons, flying P-38s and P-39s on manoeuvres. On one occasion, he took off in a P-39 and, in four minutes and five seconds, returned victorious, having 'destroyed' a squadron of P-39s with his camera gun. In November, he returned to the United Kingdom and was posted, as an instructor, to the Central Gunnery School at Sutton Bridge.

Another promotion followed in October 1942, when Malan became a group captain. In January 1943, he took command of the Biggin Hill Fighter Station, where he remained until January 1944, his duties preventing him from taking part in operational flying. He was then given the task of training 20 Fighter Wing for the forthcoming invasion of Normandy. When the circumstances permitted he took part in operations with the wing over the Normandy beaches.

Malan's next command was the Advanced Gunnery School at Catfoss where crack fighter pilots of many Allied nations were brought together to pool ideas, try out new weapons and evolve new combat techniques. In 1945 he attended a six month course at the RAF College but left the RAF the following year when he returned to South Africa.

Back home in South Africa, he first became Parliamentary Secretary to Harry Oppenheimer before taking an active part in the Torch Commando, the ex-servicemen's movement protesting against the revoking ofthe Coloured Voting Bill. He became the National President of the organisation soon after. He died in 1964.

PETRUS HENDRIK 'DUTCH' HUGO was born in Pampoenpoort in the Western Cape in 1917. After studying at the Witwatersrand College of Aeronautical Engineering, he went to the United Kingdom and attended a course run by the Royal Air Force at the Civil Flying School in Sywell. He was commissioned in the RAF in October 1939 and posted to the Fighter School at St Athan and later to 2 Ferry Pool at Filton. In December 1939 he was ordered to France, where he joined 615 Squadron, stationed at Vitry.

The squadron was equipped with Gladiator aircraft, which were soon replaced by Hurricanes. Immediately after familiarising themselves with the new aircraft, the pilots were sent into action in response to the German offensive in May 1940. During the ensuing action, Hugo managed to shoot down his first enemy aircraft, an He 111, on 20 May. When 615 Squadron resumed operations against the Luftwaffe in July 1940, Hugo destroyed six German aircraft. He was shot down on 12 August 1940, slightly wounded, but returned to action two days later. On this occasion, he suffered more severe wounds in an ambush by several Me 109s and was forced to make a crash landing. He was rushed to Orpington Hospital and, while recovering, received news that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

Wing Commander 'Dutch' Hugo (Photo: Ditsong: NMMH).

In September 1940, Hugo rejoined 615 Squadron, then at Prestwick, Scotland. During the summer of 1941, the squadron moved south, first to Northolt and later to Kenley. There, the aircraft were equipped with four cannon guns and took part in raids against enemy shipping and coastal installations in northern France. By this time Hugo had been promoted to flight lieutenant and appointed flight commander. He took control of many of the strafing attacks and assisted in sinking over twenty enemy ships, damaging a further ten and setting fire to at least three oil tanks, four distilleries and one locomotive. A number of German aircraft were also destroyed under his command. For his part in many of these diverse activities, Hugo was awarded a Bar to his DFC.

In November 1941, Hugo was promoted to squadron leader and appointed commander of 41 Squadron, which flew Spitfires. His first victories with his new squadron and aircraft were achieved in February 1942 when he destroyed one Me 109 and damaged a second during the 'Channel Dash' when the German battle cruisers, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, made their escape from Brest Harbour. Hugo was then given command of the Tangmere Fighter Wing, as wing commander. He was only able to command the wing for a short time. On 27 April 1942, during an engagement between Dunkirk and Gap Griz Nez, where he destroyed a German Fw 190 and damaged a second, his own aircraft was hit and he was forced to bale out and land in the English Channel, suffering a wound in the left shoulder. He was saved by a rescue launch. After Hugo had been posted to the headquarters of No 11 Groupto rest and recuperate, it was announced on 29 May 1942 that he was to be awarded the Distinguished Service Order for completing more than 500 hours of operational flying and outstanding work against enemy shipping. The citation ended with a special tribute: 'Both as squadron leader and wing commander this officer has displayed exceptional skills, sound judgement and fighting qualities which have won the entire confidence of all pilots in his command.'

In July 1942, Hugo took over command of the Hornchurch Wing, where he remained for six weeks before he was sent to join 322 Spitfire Wing in North Africa. He flew in support of the Allied landings in North Africa and added nine confirmed and two unconfirmed aircraft destroyed and five aircraft damaged, tq his list of victories injust over a month. On 29 November 1942 he took command of the Wing after the commanding officer had been wounded and remained in command until March 1943, when he was posted to Headquarters, North West African Coastal Air Force, and received a second bar to his DFC. In June, he was back with 322 Spitfire Wing, leading it through the campaigns in Malta, Sicily, Italy, Syria, Corsica, southern France and Italy again, where it was disbanded in November 1944. During this time he achieved a personal record of 35 enemy vehicles destroyed and a further 29 damaged in a series of strafing raids on enemy positions between 6 May and 20 June 1944.

On 10 July 1944, Hugo damaged an Me 109 over northern Italy. This was his final victory, bringing his tally to 22 enemy aircraft destroyed, four probably destroyed and thirteen damaged. He continued to fly on operations until November 1944 when he was posted to the Air Staff of the Mediterranean Air Force. Following a secondment with the Soviet 2nd Ukranian Army in Eastern Europe, he returned to the Central Fighter Establishment in the United Kingdom and served there until the end of the war. In February 1950, Hugo retired from the Royal Air Force and moved to East Africa, where he settled with his wife and children.

JOHANNES JACOBUS 'CHRIS' LE ROUX was born in South Africa in 1920. He joined the Royal Air Force after the outbreak of the Second World War and was posted to 73 Squadron in France. During the fighting in France and the subsequent Battle of Britain, le Roux was shot down and forced to bale out of burning and damaged Hurricanes on twelve separate occasions.

Squadron Leader Chris le Roux

(Photo: DNMMH).

In 1941, after the RAF had gone over to the offensive against the Luftwaffe, le Roux was posted to 91 Squadron, with the rank of flight lieutenant. Over the next fifteen months, he carried out over 200 operational sorties which included shipping reconnaissance, strafing raids on enemy air fields and ground installations, escort missions and fighter sweeps. He destroyed at least nine enemy aircraft in the air and several more on the ground and, by the end of 1942, held the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar for his actions in the line of duty. In 1943, le Roux was posted to Algeria, where he was promoted to squadron leader and appointed Officer Commanding 111 Squadron. During his three months in command of the Squadron, he shot down another five German aircraft.

No 602 Squadron, RAF, commanded by Chris le Roux, was involved in

the fierce air battles which accompanied the Allied landings in Normandy, June 1944.

(Photo: Ditsong: NMMH).

In 1944, after being awarded a second Bar to his DFC, le Roux returned to the United Kingdom, where he was appointed Officer Commanding 602 Squadron. He led this squadron throughout the fierce fighting that characterised the Allied invasion of Normandy. He shot down 23 German aircraft and then, on 19 September 1944, during a routine flight back to the United Kingdom, he was killed when his aircraft ran into bad weather over the English Channel and crashed into the sea.

JOHN DERING NETTLETON was born on 28 June 1917 at Nongoma in what is today KwaZulu-Natal. Both his father and grandfather had served in the Royal Navy and Nettleton decided to follow the family tradition by attesting for service at Dartmouth. He failed to pass the entrance exam and had to return to South Africa, where he joined the training ship, General Botha, in 1930 as a cadet. On passing out, Nettleton served eighteen months at sea in the Merchant Navy before he joined the Divisional Council in Cape Town as an apprentice engineer.

Squadron Leader J D Nettleton

(Photo: By courtesy, Ditsong: NMMH).

Nettleton was on vacation in the United Kingdom in 1939 when he saw an opportunity to join the Royal Air Force. He was accepted and commissioned as a pilot officer later that year. He served initially on Handley Page Hampden aircraft. By June 1941, he had been promoted to flight lieutenant and posted to 44 (Rhodesian) Squadron at Waddington. In December 1941, he was promoted to squadron leader and, at the same time, his squadron received the honour of being the first RAF unit to be equipped with the new Avro Lancaster Heavy Bomber.

Nettleton was to achieve great distinction in this famous aircraft during a mission planned for April 1942. The operation had four objectives: Firstly, to apply pressure against Luftwaffe fighter forces based in Europe, secondly to force the dispersal of German defences, thirdly to deflect pressure being exerted on the Allies by the German U-boat campaign in the Atlantic, and fourthly to test the capabilities of the Lancaster aircraft. It involved a daylight raid into southern Germany with the MAN Diesel Engine works at Augsburg as its primary target. The raiding force went into training in low-level flying on 11 April and consisted of twelve Lancasters, six each from 44 and 97 Squadrons, all under the command of Nettleton. On 17 April, the aircraft took off at 15.15 and made their way across the English Channel. The diversionary raids launched to draw the enemy fighters away from the bombers alerted the defences in France. Nettleton's squadron lost four aircraft in the first hour, Nettleton and the remaining aircraft continuing on course to the target. As they neared Augsburg, the two aircraft descended to tree-top height and dropped their bombs. In this dangerous manoeuvre, the fifth aircraft was hit and forced to crash land. Meanwhile, all six aircraft from 97 Squadron had survived the journey to the target, but in dropping their bombs, two aircraft were lost. The surviving bombers, with Nettleton's as the sole survivor from 44 Squadron, made their way home, aided by the dusk. Nettleton landed just before 01.00, having spent ten hours in flight. For the extreme daring and skill of the attack he was awarded the Victoria Cross while several of the other survivors received the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished Flying Cross or the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

An Avro Lancaster bomber, as flown by No 44 (Rhodesian) Squadron, RAF,

flies off in the early evening (Photo: By courtesy, Ditsong: NMMH).

In 1943, Nettleton was promoted to wing commander. On 13 July 1943, he was declared missing in action after his Lancaster failed to return from a raid on Turin. He and his crew, having no known grave, are commemorated on the Memorial to the Missing at Runnymede.

EDWIN ESSERY SWALES was born in Inanda in KwaZulu-Natal in July 1915. As a child, Swales joined the Boy Scout Movement and, after leaving school, he worked for Barclays Bank in Durban. He joined the Natal Mounted Rifles (NMR) before the war and attained the rank of Warrant Officer, Class Two. During the early part of the Second World War, he saw service with the NMR in East and North Africa. On 17 January 1942, he was transferred to the South African Air Force. He was presented with his wings in Kimberley on 26 June 1943. A few months later, on 22 August 1943, he was seconded to the Royal Air Force but retained his SAAF uniform and rank.

Major Edwin Swales

(Photo: Courtesy, Ditsong: NMMH).

Following a successful period of training on heavy bombers, Swales was posted to 582 Squadron based at Little Staughton in Huntingdonshire. This Squadron was part of 8 Pathfinder Group of the elite RAF Pathfinder force. Even though appointments were restricted to experienced pilots who had completed a full tour on bombers, Swales was accepted without having spent any time as a pilot in a bomber squadron. He took part in his first operational flight with the squadron on 12 July 1944.

In November 1944, Swales was promoted to the army rank of captain (the RAF equivalent being that of a flight lieutenant). In December, he took part in a daylight raid on the Gremberg railway yards in Cologne. During the raid, the master-bomber's aircraft having crashed, Swales had to take over the target marking duties. Six of the thirty aircraft that took part in the operation were lost. For his actions during the mission, Swales was awarded the DFC in recognition of his gallantry and devotion to duty in the execution of air operations.

RAF Lancaster bombers fly over the English countryside

(Photo: Ditsong: NMMH).

On the same day that his DFC was gazetted, Swales, who had recently been promoted to the army rank of major (the equivalent RAF rank being that of squadron leader), was chosen to command a raid on Pforzheim, not far from Karlsruhe and the Rhine River. During this mission, his aircraft was attacked by the cannon of an Me 110, which shattered one engine and ruptured his fuel tanks. Unperturbed, Swales carried on his mission and issued aiming instructions to the main force. A second attack by the same aircraft knocked out another engine, which put the aircraft out of action. Almost defenceless, Swales remained over the target area issuing aiming instructions until he was satisfied that the attack had achieved its purpose.

Struggling to keep his Lancaster in the air and with the blind-flying instruments no longer working, Swales was determined not to let the aircraft and crew fall into enemy hands and set course for home. He kept his course through skilful flying between layers of clouds. Eventually, after reaching friendly territory and realizing that the situation had become desperate, he ordered the crew to bale out. It required every effort he had to keep the aircraft steady while each of the crew jumped in turn. Finally, after the last crew member had jumped, the aircraft plunged to earth. The Lancaster crashed near Valenciennes in France, about 250 miles (400 km) west of Pforzheim. Swales was found dead at the controls.

Swales' grave is located in the War Cemetery at Leopoldsburg near Limberg in Belgium. In recognition of his most conspicuous bravery, Swales was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. He was the only SAAF pilot to be appointed a Pathfinder MasterBomber during the Second World War and was the third and last Pathfinder pilot to be awarded the VC. The Pforzheim raid was his 43rd flight in 582 Squadron. His mother, Mrs Olive Swales, unveiled the Stone of Remembrance which commemorates the South Africans who fell in all theatres of the Second World War and which is situated in front of the arch of the South African War Memorial in France.

An Avro Lancaster, as flown by No 582 Squadron, RAF,

takes off into the dusk (Photo: DNMMH).

JAMES THOM 'JIMMY' DURRANT was born in Johannesburg in May 1913. He was educated at St John's College. He joined the Transvaal Air Training Squadron while he was studying engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand. Realising that his future lay in flying rather than engineering, he joined the South African Air Force as a cadet in 1933 and qualified as a pilot a year later.

Durrant served as a flying instructor in the SAAF until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. In 1940 he was promoted to major and appointed Officer Commanding 40 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, SAAF, in East Africa. A year later he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and appointed Officer Commanding 24 Squadron, SAAF, before taking command of 3 Wing, SAAF, in North Africa, Sicily and Italy with the rank of colonel.

In 1944 Durrant was seconded to the Royal Air Force, retaining his SAAF uniform and rank. He was immediately promoted to the rank of brigadier (equivalent to the RAF rank of air commodore) and appointed Officer Commanding 205 Group in the Desert Air Force.

Pilots of Hawker Hartbees aircraft of No 40 (Army Co-operation)

Squadron, SAAF, at an airfield in East Africa, 1940.

Durrant was the mastermind of the mining operations on the River Danube in 1944. At the time, Germany's oil resources were being transported from Ploesti in Romania along the riverto Vienna in trains of barges towed by tugs. All attempts to bomb Ploesti had met with heavy losses. Durrant devised a scheme to drop magnetic mines into the Danube on moonlit nights from exactly 30 feet (9,14 metres) above the water and embed them into the banks. This mission was undertaken by Consolidated B-29 Liberator aircraft of 2 Wing, including 31 and 34 Squadrons, SAAF. It was so successful that it cut off the flow of oil and, in retrospect, is seen as one of the most effective air operations ever conducted in southern Europe. Durrant also played a role in the relief flights that were flown by the Liberator squadrons of 2 Wing from Italy to Warsaw to supply the beleaguered Polish Home Army in September and October 1944 After receiving his orders, Durrant confronted Winston Churchill regarding the dangers inherent in such a low-level operation. Although the British statesman agreed with him, he nevertheless ordered the operation to go ahead, for 'propaganda value'. The Liberators flew 181 sorties to Warsaw with a loss of 31 aircraft.

Following the victory in Europe in May 1945, Durrant was posted to the Far East. He was promoted to major-general and appointed Air Officer Commanding 231 Group. (He was the youngest member of the British/Commonwealth forces to attain the rank of general/air officer during the war, the equivalent RAF rank being air vice-marshal).

Brigadier Jimmy Durrant

(Photo: Courtesy, Ditsong NMMH).

The heavy bomber group under his command was intended to form part of the forces mobilised for the re-conquest of Malaya. However, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the subsequent surrender of Japan rendered this task unnecessary, and Durrant returned home to South Africa.

For his leadership and gallantry, Durrant was created Commander of the British Empire, awarded the DFC, Mentioned in Despatches and received the United States Legion of Merit (Officer Class). His log books reveal that he flew 42 different types of aircraft during the war. On return to South Africa, he was granted the substantive rank of brigadier in the Union Defence Forces and was appointed Director-General of the South African Air Force in 1946. He held this post until February 1952, when he resigned owing to his irreconcilable difference of opinion with regard to the policies of the National Party Government. He served for eight years as a Johannesburg City Councillor, which included a period as a member of the Board of Trustees of the South African National War Museum (now the Ditsong: National Museum of Military History). He died on 15 October 1990 and was buried with full military honours. His medal group is on display at the Ditsong: National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg.

The records of service of these seven South Africans in the Royal Air Force stand out as a shining example of what our countrymen achieved in the Second World War. The Ditsong: National Museum of Military History considers it important that the memory of these men and those of the thousands of other individuals who also served with distinction, be preserved for generations to come.

References

Archival files, 920 Durrant, J T; Hugo, PH; Le Roux, JJ; Malan, AG; Nettleton, JD; Pattle, M St J; and Swales, EE,

in the Lt Gen AML Masondo Library and Archives, Ditsong: National Museum of Military History, Saxonwold, Johannesburg.

Baker, FCR, Fighter Aces of the RAF, 1939-1945 (London, Kimber, 1962).

Bennet, D, 'Major Edwin Swales VC, DFS, South African Air Force' in Military Medal Society of South Africa Journal, No 43, December 2007, pp 38-42.

Hamilton, A W, 'Lest We Forget' in Fighting Forces of Rhodesia, No 4, pp 31-9.

Shores, C, Williams, C, Aces High(London, Spearman, 1966).

_I

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org