The South African

The South African

'The past is constantly shifting.'

Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge

During this time, he was based variously at Port Elizabeth (Coega), Somerset East and Cape Town (the Castle). At one time, charged by Sir George Grey, he was responsible for the shipping of 1 500 horses to India to be used in. the Indian Mutiny. Most of these horses had been bred on inland farms by Boers, and were only half-broken. Brabant would attach slings and headlines to them and, with four Xhosa men holding them, run them into the surf at Algoa Bay and hoist them into a surfboat, which took them to a coastal steamer, the Waldesian, waiting in the roadstead. Here, Brabant (and a veterinary surgeon, if available) would accompany them to Cape Town, taking personal care of them. Of the 1 500 horses he shipped this way, he only lost two percent, as against seventeen percent lost from being shipped from Australia (The Life of Sir E Y Brabant, p 21).

Major-General E Y Brabant, KCB, CMG

(Photo: By courtesy, Buffalo Volunteer Rifles).

In 1865, Brabant married Miss M B Robertson in England and later returned to South Africa where he was stationed (as captain) at Fort Beaufort, where, while acting as adjutant, his eldest son was born. The War Office reduced the CMR by two troops and, in 1870, the regiment was disbanded. Although he had served for fourteen years with the regiment, he chose not to return with it to England, but took leave on half-pay. He retired with the rank of captain, and began farming at Gonubie.2

Painting of Brabant's farmhouse

2 Brabant bought the farm Gonubi [sic] Park 'at a very low price' and with 'the idea of making it a sort of seaside resort for the (Cape Mounted) regiment.' The farm was about ten miles (16km) from East London and was his and his family's home for more than thirty years. He built the house from timber salvaged from the wreck of the Quanza, having bought the 'right of the beach' to have whatever floated ashore. ('The Life of Sir E Y Brabant', p 45).

3 The Buffalo Volunteer Rifles was also known as the 'Buffalo Volunteers', the 'BuffaloRifles' or simply 'the Buffs'. It was decided at its inception to make it independent of the Kaffrarian Volunteers of King William's Town, which had been in existence since 1870. On the history of these two corps, whose names were often confused, see Coleman, 1986, pp1-20.

5 Early in the Gcaleka campaigtn, C D Griffith, who commanded the Kaffrarian Volunteers in 1870 when he was Resident Magistrate and Civil Commissioner in King William's Town, was placed in charge of the FAMP (Frontier Armed and Mounted Police), Lieut-Col Lambert was sent from Cape Town to command the 88th Regiment (the Connaught Rangers), and later Col R T Glyn took over from Griffith to direct operations east of the Kei.

Lieutenant Brabant and officers of the Cape Mounted Riflemen (Imperial).

(Photograph: By courtesy, Buffalo Volunteer Rifles Museum, East London).

Bailie's Grave Post6

When Lieutenant-General Thesiger arrived to take overall command of the combined Imperial and Colonial forces in King William's Town, Brabant was ordered with his corps to Bailie's Grave Post, halfway between King William's Town and Keiskamahoek. At Bailie's Grave Post, Brabant's force comprised 169 men of his own 291-strong unit, as well as 125 Mfengu. After several campaigns culminating in the death of Chief Sandile in May 1878 and the surrender of other chiefs, Brabant participated in mopping-up operations. Soon afterwards, he was ordered to lead the first regiment of the newly-raised Cape Mounted Yeomanry - also known as the CMY Troops, which comprised the Grahamstown, Bathurst and Maclean[town] men as well as the famed rough-and-ready East London 'boatmen' who had fought under Brabant in 1877 (Coleman, 1986, p 25) - and assemble the 1 st Battalion against the Sotho Chief Morosi in the so-called Basuto War. (For details concerning these operations, see 'The Life of Sir E Y Brabant', pp 72 ff.)

As mentioned earlier, during the second half of the Ninth Frontier War, Lieutenant-General the Honourable F Thesiger (later, the second Lord Chelmsford) was sent from England to replace General Sir Arthur T Cunynghame as overall Commander of both the Imperial and the Colonial forces in the Cape - an unprecedented, but successful, military experiment. Together with his Assistant Military Secretary, Major John North Crealock, Colonel Evelyn Wood, and the 90th and 24th Regiments, General Thesiger arrived at East London at the end of February 1878, and entrained for King William's Town where a temporary war office under Merriman had been set up.

By 17 March, after a reconnaissance of the area, Thesiger had established his field headquarters at Haynes' Mill8 in the Pirie Forest near the Pirie Mission, and placed his combined forces (all under Imperial command) at six different stations. Crealock writes: 'Generally, the forces were placed as follows: Baillie's [sic] Grave Post and neighbourhood facing east, Capt[ain] Brabant, 287 total. On his left head [sic] 2 r[egiments] at Keiskamahoek, Col[onel] Wood VC, CB, 400 total; on his left again facing south about Fort Merriman, 697, C[ommandan]t Frost (Major Buller CB his staff officer), - on his left facing S W C[ommandan]t Schermbrucker [at Isidenge}, 669 men Captain Gossett ADC acting as his staff officer - connecting with him facing west was Colonel Degacher with the headquarters of 2[nd] [battalion] 24th regiment and two [seven [pounder] guns at the mouth of the Cwengwe [sic] valley - connecting this force with that post named after C[ommandan]t Brabant was a wide stretch of open country. The troops holding the posts at Haines's [sic] Mill and Perie Mission Station, 656 men and [two 7-pounder] guns, were under the immediate command of the General, numbering 555 infantry, 1 185 mounted men, 1 295 natives - [a] total [of] 2 899 [men] and [four] 7 -p[ounder] guns (Hummel, 1988, pp31-4).

His plan was to lure the Ngqika from the forests or 'bush' in which they were hiding, by using Mfengu volunteer units. They would then be driven eastwards to forces stationed at Isidenge (under Colonial Commandant Schermbrucker) and at the mouth of the Cwengcwe Valley (under Imperial officer Colonel Degacher) where the rebels would be finished off with rifle fire and 7-pounder guns.

The first offensive was planned for Monday, 18 March. On Sunday afternoon, 17 March, the forces were in position and ready to attack the next morning at daybreak. According to Major John Crealock, Thesiger's Assistant, the plan of action was as follows: '[T]he force under the immediate orders of Col[onel] Wood from Keiskamahoek was to push on to the heights called Gozo and be there at 06.00 while those of C[ommandant]s Brabant and Frost were to conform to this movement respectively, the three forces holding out a hand to each other. On reaching the high ground [they] were to drive the rebels eastward where Cmdt Schermbrucker would be ready to head them; while the troops to the south would act as seemed most desirable according to the line the rebels took.'

Crealock continues with his report: 'March 18: Headquarters staff left camp at [04.00] for Bailie's Post; bright moonlight but up the worst conceivable road; reached [the] Post at daybreak and found Capt[ain] Warren R[oyal] E[ngineers] and Diamond Field[s] Horse awaiting orders to move. Nothing was to be seen of Brabant's force. With a glass in the very far distance men could be seen moving, however, that (sic) [They] may have been his. This seemed odd as it did not appear to us possible that Col[onel] Wood's force could have reached his (sic) [this] point by that hour. By subsequent information we learnt that Brabant had left camp earlier (11 pm previous night) than intended and had pushed on in advance thus rendering any combined action with the officers (sic) under whose orders he was (Col[onel] Wood) impossible. This mistake was most unfortunate. Brabant's men were led on into a position whence they were only extricated by the assistance of those whose presence was needed elsewhere (Shealpied's (sic) [Streatfeild's] Fingoes). Brabant's men suffered heavily in consequence. The Caffres [sic] gained confidence with their success and this day's combined attack was nullified by this precipitate action, but this was unknown to the general for 12 hours after.' (Crealock in Hummel, 1988, pp 35-6).

Colonel (later Field Marshal Sir) Evelyn Wood provides this succinct report of the event: 'Captain Brabant had an easier ascent, up which, indeed we took waggons [sic] two months later. When he gained the crest at daylight, he saw two miles (3,2km) below him to the eastward, some Kafirs [sic] and cattle in an open glade, and advanced until he had dense bush on either hand. The Kafirs [sic] opened fire, and Brabant fell back with some slight loss, Streatfeild who went to help Brabant out, having an officer killed. The impatient disregard of orders spoilt the General's plan (Wood, 1906, Vol 1, P 306).

A footnote to Wood's memoirs (p 306) explains that 'The Colonial papers attributed Brabant's reverse to Colonel Wood having for some reason failed to support him. Our Burghers only laughed at the local paper but it was published in the Times.' Wood might have been generous in not censuring one of his Colonial commanders more roundly for putting him in this awkward position, but he stresses the lightness of Brabant's ascent ('he had an easier ascent') and his use of the phrase 'impatient disregard of orders' clearly shows his irritation and disapprobation of his subordinate's behaviour.

Subalternity

This, and other military responses to the incident, invite a reading in terms of the subaltern approach - the term 'subalternity' referring to a condition of subordination brought about by colonisation or other forms of economic, social, racial, linguistic, or cultural dominance. Although these exact conditions do not obtain here, the writer argues that the military histories of the Brabant incident can be read as a variation of the subaltern effect - a perceived superiority deriving from an implicit Imperial/Colonial rivalry. The accounts examined of Brabant's attack and reverse are written by military men, all of whom, with one exception, were Imperial officers. The writer argues that there was not only a tacit rivalry between the Colonial and Imperial forces, but at times a tissue of suspicion and dominance runs through their accounts of one another's actions. (Subalternity studies arose in South Asia in the 1980s. Although it is often seen as a subset of post colonialism, John Beverley stresses that '[S]ubaltern studies is not only a way of thinking about a colonial or formerly colonial other' (Beverley, 1999, p 19, his italics) but 'a place where people with different convictions and agendas, but committed to the cause of social equality ... can work together' (Beverley, 1999, p 23).

While it has been commented on by more than one military writer that outwardly there was no discord between them in the Amathole operations, there was, as the Brabant incident shows, implicit unease, manifest in a vying for dominance. Both Imperial and Colonial officers are under the same sky, but have different horizons: They might be engaged in the same pursuit of fighting Sandile's Ngqika, but each has personal validation or aggrandisement as his goal. (See Crealock in Hummel, 1988, pp 25-6: 'Major Buller was now to be attached in like manner to Com[mandant] Frost - a novel proceeding here but one that was found to answer admirably [the needs of the situation] - on the other hand it shewed that the Colonial officers were quite ready to meet us halfway in any measure of mutual co-operation'. See also General Sir A T Cunynghame's more patronising remark concerning operations against the Gcaleka (and some Ngqika) in 1877: 'I have always had a high opinion of the volunteers themselves, and am certain that if they had only been placed under military command their services would be more valuable than they were.' [Cunynghame, 1880, p 368).

Streatfeild9

Frank Streatfeild, the Commandant of a Mfengu levy swelled the night before by an additional 300 from Captain Lonsdale's levy, left his base at Rabula Camp with his men 'sometime between one and two am.' Both Streatfeild and Brabant were English by birth, but as they had been living in South Africa for several years and had been placed in command of local volunteer units, they were regarded as Colonial officers.

On receiving Brabant's message, although much wondering how it came about that he was engaged with the enemy more than a mile from the place where I was ordered to join him ... I hastened down with my men to his assistance ... The firing had been for some time and still was very heavy and on our way down we met many wounded men being carried out of action. We soon arrived in the middle of the fighting ... cleared first one part of the bush and then another, killing a few Kafirs [sic] ...

After about two hours' fairly hard work, with more "bushwhacking" than fighting, and the Kafirs [sic] being completely silenced and driven into the depths of the forest, we returned to the top of the ridge. Brabant, had, I think, lost five men, and had six wounded, and also thirteen horses killed. I only lost one man .. .' (Streatfeild, 1879, pp 111-116.)

Here, almost imperceptibly, a brother Colonial officer produces an example of implicit dominance. Brabant is presented as 'begging' him for assistance, and the enemy is in 'great force', whereas in reality the numbers of assailants were probably difficult to descry in the thick bush. (No report hazards numbers.) In heroic mode, Streatfeild 'hastens' to his errant fellow officer's help, the firing has 'been going on for some time' and is 'heavy', with 'many wounded men being carried out of action', and 'after two hours fairly hard work' they manage to repulse the enemy.

The prose of dominance then becomes more explicit as it moves into overt censure and blame: 'This premature attack of Brabant's had been productive of no good whatever, and had entirely upset all the proposed operations of the day. I was forced to go to his assistance when sent for, and therefore both his force and mine were lost for the day, as far as the combined attack went; and also, on account of this, Wood's and the other corps remained in a state of inactivity.' (Streatfeild, 1879, p116.)

Perhaps feeling that he had been a little too severe in his denunciation of his fellow commandant, in a later description of working together on another offensive with Brabant, Streatfeild makes a gesture of amends: 'Brabant was with me, and stuck to his word like a brick, in spite of his being somewhat stiff about the knees.' (Streatfeild, 1879, p 132).

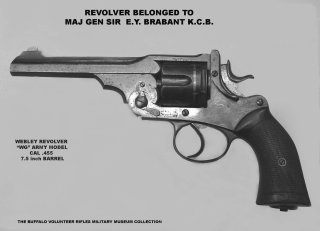

General Brabant's Webley revolver

(Photo: By courtesy, Buffalo Volunteer Rifles Military Museum Collection, East London).

Molyneux

In his report of the event in his memoirs, Imperial officer Major-General W C F Molyneux, who formed part of Thesiger, Wood and Buller's party, also refers to the incident but goes further in paternally trying to attribute a reason to Brabant's implied impatience: 'It turned out that the spirit of cattle-lifting, the curse of South Africa, was responsible for the failure of the scheme. Brabant, with his Volunteers and Fingoes [sic], finding there were cattle in front, would not wait for Wood to come up in line, but went on at once, the temptation being too strong for undisciplined men. They fell into the ambuscade, and were so roughly handled that they ran away.' (Molyneux, 1896, p 52).

Molyneux's attitude towards Colonial officers is ironic. He was fully aware of the importance of capturing cattle as a means of crippling the enemy's commissariat (Molyneux, 1896, p 54), and there is no indication that he refused to partake of the beef from enemy cattle at the mess hour. In his description of Brabant's attack, the tropes of insidious blame and superiority creep in: 'would not wait for Wood ... the temptation being too strong for undisciplined men', culminating in the final dastardly thrust: 'were so roughly handled that they ran away'.

No other accounts (and Molyneux was not an eyewitness) mention Brabant and his men running away. Wood implies that he fell back, fighting. Streatfeild, who came to Brabant's aid, writes that they [Brabant and his men] 'were engaged with the enemy', and that '[t]he firing had been for some time and still was very heavy and on our way down we met many wounded men being carried out of action'. (Streatfeild, 1879, pp 115-116).

Brabant's account

Finally, let us look at Brabant's own account of the incident, which, like those of Streatfeild and Molyneux (Crealock's being the exception), was written some decades after the event. Brabant (in 'The Life of Sir E Y Brabant', p 66) writes: 'My orders were to take up a position near the head of the "Evelyn Valley" by daybreak, and then to move forward in concert with all the other columns. In obedience to my instructions I got [i]nto my assigned position before daybreak but when the sun rose no other force than my own was to be seen, and a few Kaffirs [sic] and some horses and cattle were to be seen just below us. My men were always very keen to capture cattle, and as the kaffirs [sic] were now aware of our presence, and all idea of surprising them was over, I determined to make a dash for the cattle. This I did but the natives' position turned out to be stronger than I supposed. A heavy fire was opened from the bush on both sides of the valley, and as the cattle had cleared into the bush and nothing more could be done, I recalled my men to our original position at the top of the hill. Nothing more was done by any of the columns. I was very much blamed at the time for advancing without orders, but I failed to see then - as I still do - how my advance could affect the combined movement, which could not in any case have been successful, owing to the unexpected strength of the ground held by the enemy. The real fault lay with those who reach[ed] their positions too late. I had four or five men hit one mortally.'

Brabant seems to feel that by the time of writing his memoirs, as Brigadier-General Sir Brabant, MLA, he hardly needs justification. He is recognised by all in South Africa and abroad as a trustworthy, reliable source of warrantable information that needs no further certification. (For a definition of these concepts, see Kirkham, 1992, Volume 1). Brabant justifies himself perfunctorily by suggesting that his early arrival gave him time to attack what he saw as a small group (he is later disabused of this illusion) and capture their cattle. He defends himself by saying that, as the enemy had seen them, he could lose nothing by pursuing the cattle. His use of the word 'dash' implies that he estimated that his raid would be speedy, and that he would still be in position for the concerted attack. Then he adopts an injured tone, maintaining that he cannot understand why his premature attack could have derailed the combined assault. Finally, he blames the other units for reaching their positions too late. If they had been there on time (it is implied) he would not have been tempted to go after the cattle.

Brabant gives as good as he gets and so the blame cycle continues: His men were 'very keen' to capture the cattle (why did he not control them?) and, more outrageously, it was the fault of the other units for being late - an allegation unsubstantiated by other reports. (In his edition of the War Journal of Major John Crealock (1989, p 39, fn 48) Chris Hummel attempts to palliate the charges against Brabant by suggesting that he never outgrew his boyish traits of being 'shy, timid and dreamy' and that he 'had trouble disciplining his men as a junior officer'. This may have been the case when he was young, but since then Brabant had not only raised and commanded the Buffalo Rifle Volunteers and the Lilyfontein Levy, but successfully engaged with the enemy west of the Kei, killing the Chief Ludidi [sic] in one of his offensives. (See the commendatory dispatches from Sir John X Merriman, quoted at the end of this article on p 229.)

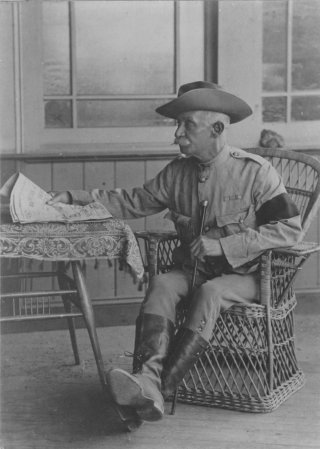

Brigadier-General E Y Brabant during the AngloBoer War

(Photo: By courtesy, Buffalo Volunteer Rifles Museum, East London).

While the writer feels that Brabant's two final accusations are ungenerous, with the last one not proven, she believes that Brabant's permitting his men to pursue the cattle can be understood in terms of the norms of Frontier warfare. Firstly, leaders and commandants of Colonial units, or levies, were used to exercising their own judgement, making their own decisions, and generally acting more independently than their Imperial counterparts. Secondly, as mentioned earlier, it was important that enemy cattle be captured, as this depleted their milk supply (a staple food) and weakened their physical strength. The amaXhosa always took their wives, children, cattle, and flocks with them to war, erecting thorn stock enclosures in forest glades and taking their milk baskets with them so that they could subsist on milk. The women, who were not allowed to tend or milk the cattle (this being the men's job), foraged for roots, ground and cooked the grain (maize or sorghum) that they brought with them, stored and served the sour milk, and raided Colonial farms and military stores. They also procured information, and ammunition - powder and lead - which they hid under their umbaco (blanket-skirts) (Cunynghame, 1880, p 373; Wood, 1906, Vol I, p 307/). In this way, Xhosa women (not unlike Boer women during the Anglo-Boer War) acted as 'intelligence and commissariat' (Molyneux, 1896, p 54).

The capture of cattle

The cattle the Imperial and Colonial troops captured from the amaXhosa were kept temporarily in camp and then driven to the nearest town to be sold, the proceeds being divided equally between the officers and men. Some of the cattle were slaughtered for eating, a welcome addition to their mess, which comprised mainly army biscuit, tinned (Cambridge) sausages in brine, boiled, dried or salt beef and the occasional bushbuck steak (Hummel, 1988, p 45 [The memory of a Bush Buck Steak and a tin tot of tea'], and see also Streatfeild, 1879, p 159).

All the memoirs of Colonial and Imperial officers mention rounding up enemy cattle as par for the course. Streatfeild (1879, p 120), cheerfully admits that his own men rounded up enemy cattle: 'We were employed in scouring the bush round the two plateaus [sic] most of the day, and had a certain amount of fighting, and captured some cattle and a good many horses. My own corps, I believe, got about 120 head of cattle, which I am thankful to say were almost immediately stolen from them and driven away by some other Fingoes.'

Streatfeild (1879, p120) goes on to explain that he is relieved because having cattle in camp is a tiresome (but, by inference, not forbidden) business: 'I would never willingly have a single head of captured cattle in my camp. 'Le jeu ne vaut pas la chandelle,' for a guard has to be supplied, the men are always disputing, and over-eat themselves to such an extent that many of them become sick and useless.'

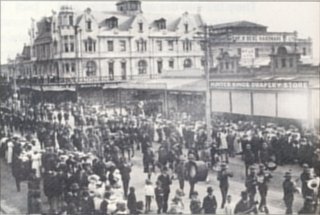

Two views of the funeral of Major-General Sir Edward Yewd Brabant, KCB, CMG.

Seizing cattle during Frontier warfare therefore served a double purpose, and was actively encouraged. In fact, it was frequently expressly commanded. (See, for example, Captain Charles Bailie's explicit brief to recover stolen cattle during the War of 1834/5 in Wilmot, 1904, Appendix I, pp 430-31. Commandant Holden Bowker's journal entry for May 1835 (the invasion of Gcalekaland) reads: 'Captured cattle, 11 000 in number to be sent home', in Mitford-Barberton, 1970, p 130). In almost every official report after an engagement with the enemy during the Ninth Frontier War operations in the Transkei and Tyityaba Valley, it was proudly added how many hundred or thousand head of cattle had been taken - which earned them the praise of the War Office.

A perusal of the unpublished Brabant papers shows a number of such reports and dispatches, including a laudatory reply from Sir John X Merriman, commending Captain Brabant for his 'energy and skill' in locating and engaging with the enemy so successfully and capturing enemy cattle (CA A 459 Brabant File 129 1877/8, C35 'Nesbitt's Farm'). There is also a warmly commending letter from Merriman, dated King William's Town 25 January 1877(with the correction '1878' next to it by another hand) in which he praises Brabant for a 'successful. .. engagement' (during which the Chief Ludidi was killed) and for capturing a 'considerable number of cattle' (Brabant File 129 1877/8, C 36 1878).

High-ranking British officers not only considered it their duty to capture enemy cattle, but were pleased to do so. During the invasion of Zululand, which followed hot on the heels of the quashing of the 1877/8 Ngqika Rebellion, Evelyn Wood writes: 'I had an interesting talk with Lord Chelmsford [Thesiger] for three hours, while Colonel Buller was sweeping up cattle to the south of the General's line of advance' (Wood, 1906, Vol II, p29). Previously, at Balte Spruit near Blood River, Wood had written: 'When, after the 11th [January], Colonel Buller seized a large number of cattle, I asked some of the Zulus why they had not driven them off ... ' (Wood, 1906, Vol II, p28), without a word of reprimand for his fellow officer; but rather, as the context shows, with approbation.

General Sir Arthur T Cunynghame, Commander-General of the Cape prior to Thesiger's arrival, notes with complacence in his memoirs the amount of cattle ('upwards of 8 000 head of cattle and as many sheep') Colonial and Imperial forces captured during the 'Transkei operations' in 1877 and early 1878 (Cunynghame, 1880, p366) .

With such precedents in mind, Brabant must have felt more than a measure of justification in allowing his 'keen' men to go after the cattle they saw, especially as they had time in hand before their combined operation.

On outside back cover of the Journal:

The medals of Major-General Sir E Y Brabant, KCB, CMG:

Top left: CMG (Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George) neck badge

Bottom right: KCB (Knight Commander, Order of the Bath) neck badge and breast badge

Brabant's other medals seen here are:

South African Medal 1877-79 (9th Frontier War)

Cape of Good Hope General service Medal (Basutoland)

Coronation Medal Edward VII

Queen's South Africa Medal (Anglo-Boer War), and

King's South Africa Medal (Anglo-Boer War)

(Photographs: By courtesy, The Buffalo Volunteer Rifles, East London)

LIST OF SOURCES

ARCHIVAL SOURCES

CA A 458/439 'The Life of General Sir E Y Brabant'.

CA A 459 Brabant File 1291877/8, C35 'Nesbitt's Farm'.

CA A 459 Brabant File 129 1877/8, C 36, Letter from John X Merriman to Captain E Y Brabant, 25 January 1877.

CONTEMPORARY SOURCES

Cunynghame, General Sir A T, My Command in South Africa, 1874-1878 (London, 1880).

Fleming, Revd Francis, Kaffraria and its Inhabitants (London, Smith and Elder, 1853).

Hummel, C (ed), The Frontier War Journal of Major John North Crealock: 1878, A Narrative of the Ninth Frontier War by the Assistant Military Secretary to Lieutenant General Thesiger(Cape Town, Van Riebeeck Society, 1988-89).

King William's Town Gazette, 1877-1878.

Mitford-Barberton, I, Comdt Holden Bowker (Cape Town, Human and Rousseau, 1970).

Molyneux, Major-General, W C F, Campaigning in South Africa (London, Macmillan, 1896).

Streatfeild, Frank, Kafirland: A Ten Months' Campaign (London, Sampson and Low, 1879).

Wilmot, The Hon Alexander, The Life and Times of Sir Richard Southey, KCMG (London, Samson, Low, Marston and Co, Cape Town, Maskew Miller, 1904).

The History of our own Times in South Africa: 1872-1879 (London,Cape Town, Juta, 1897).

Wood, Sir Evelyn, FM, VC, GCB, GCMG, From Midshipman to Field Marshal, 2 vols (London, Methuen, 1906).

SECONDARY SOURCES

Beverley, J, Subalternity and Representation: Arguments in Cultural Theory (Durham, Duke University Press, 1999).

Burton, Alfred W, Sparks from the Border Anvil (King William's Town, Provincial Publishing Company, 1950).

The Highlands of Kaffraria: A View of Outstanding Events in Kafirland and British Kaffraria Leading up to rise of King William's Town, Keiskamahoek and East London, with special reference to the history and situation of Fort Stokes (Cape Town, Struik, 1969).

Coleman, Francis, L, 'Nunc Animis': The Kaffrarian Volunteers, 1876-1986 (East London, The Kaffrarian Rifles Association, 1988).

Foucault, M, The Archeology of Knowledge, tr A M Sheridan-Smith (London, Routledge, 1994).

Habemas, Jurgen, Truth and Justification, tr. Barbara Fultner (Cambridge, Polity, 2003).

Kirkham, Richard, L, Theories of Truth: A Critical Introduction (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1992).

Sosa, Ernest (ed), Knowledge and Justification, Vol 1 (Vermont, Dartmouth, 1994).

Tshabe, S L et al (The) Greater Dictionary of isiXhosa, 3 vols (Alice, University of Fort Hare, 1989-2006).

INTERVIEWS

Mrs Nancy Brabant Wainwright (East London)

Major Tony Step, Buffalo Volunteer Rifles (East London).

The author gratefully acknowledges the following people

for their kind permission to produce the images mentioned below:

Mrs Nancy Brabant Wainwright for the painting of Brabant's farmhouse at Gonubie.

The Buffalo Volunteer Rifles, East London, for the portrait of General Sir

E Y Brabant, the Cape Mounted Riflemen, Brabant during the Anglo-Boer War, Brabant's medals, and his Webley.

Major Tony Step for other material on Brabant and the Buffalo Volunteer Rifles.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org