The South African

The South African

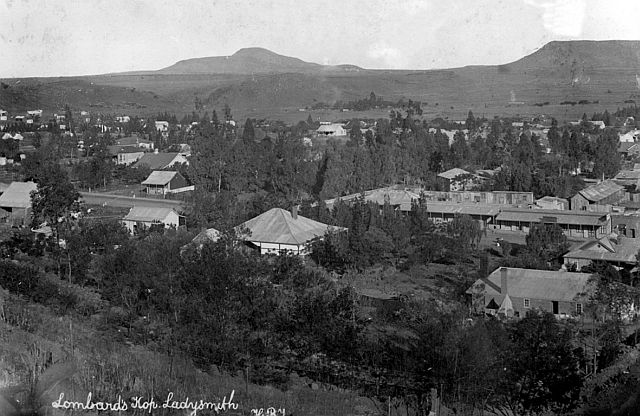

Gun Hill, near Ladysmith

It was obvious to certain civilian observers, such as William Watson, that, in order to break the deadlock in Ladysmith during the Siege of November 1899 to February 1900, it would be essential to storm the Boer artillery emplacements, whatever the cost in lives. Yet, it was not until early December that such an attempt was made on Gun Hill.

Once the tentative engagements of early November had passed, Sir George White resisted calls for offensive action, despite the apparent eagerness of the garrison. On, or shortly before, 1 December, the Boers created a gun emplacement on Gun Hill and transferred there the Creusot 6-inch (Long Tom) gun, dubbed 'The Stinker' by the besieged, from Pepworth Hill. It was then closer to the British-colonial positions, and became a tempting target for a raid, especially after its bombardment of the Imperial Light Horse camp on 2 December.

The planning for the attack on Gun Hill also inherited the controversy surrounding British laxity in permitting the Boer occupation in the first place of Bulwana and Lombard's Kop, in the immediate vicinity of Gun Hill, during the last days of October. Natal Volunteer Orders for 29 October revealed a plan for 200 Natal Carbineers to occupy both Bulwana and Lombard's Kop. It had never been put into effect. British Intelligence had incorrectly concluded that it would be impossible to get heavy weapons onto the summit of Bulwana, which would in any event be out of range of Ladysmith, and that water was not available. White's sanction for the raid was secured only with some difficulty, with the proviso that Major-General Sir Archibald Hunter, his Chief-of-Staff, lead the expedition in person, with a force of at least 500 men.

The attack was also apparently in response to the shelling of the Town Hall hospital on 30 November. This incident elicited outrage from British observers such as Donald Macdonald, who quoted a harsh reaction from an unnamed Carbineer: 'I heard one of the Carbineers say, with clenched fists, "and may God Almighty help the first Boer who asks me for quarter.''' (Macdonald, 1999 reprint, p 107; NAR, Leyds 1043, CD 458, White to Chief-of-Staff, 23 March 1900, pp 19, 20; Gill, Lieutenant D Howard, 21st Battery, Royal Field Artillery, confidential diary, Transvaal War 1899-1900, 30 November 1899, p 93; and Natal Mercury, 9 December 1899). The decision to proceed with the operation was also influenced by the motivation of Major C B Add ison, a staff officer with the Natal Carbineers, who pointed out that this was a rare opportunity offered to the Volunteers to distinguish themselves. In the light of the criticism directed at White for retaining cavalry during the siege, it was significant that this was a dismounted operation, which called for the use of wire-cutters and sledgehammers.

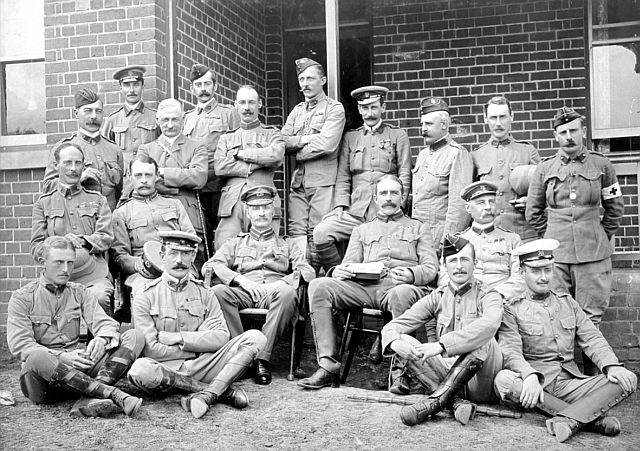

The Natal Carbineer component once again read like a 'who's who' of Natal colonial society. Apart from Major Addison, the officers present are listed below:

Major

The force made history with the inclusion of Pietermaritzburg's 'first citizen', Major George James Macfarlane, JP, CMG, FAA, probably the only serving mayor in South African history to participate in such a military action in any war. Macfarlane, a born Natalian, earned a full page spread in the Natal Illustrated in 1902 on account of his distinguished civil and military accomplishments - he was also a Zulu War veteran. He served four years as the mayor of Pietermaritzburg. The Illustrated reported that he was responsible, inter alia, for the extension of the 1901 South African Royal Visit of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught and York to Natal, and was largely responsible for their arrangements in Pietermaritzburg. In business circles, he was a stock and share broker, accountant, and general agent, and secretary to several companies. His CMG (Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George), granted after the War, was a reward from the Imperial Government for his military service. The Macfarlane foot-bridge over the Umsindusi River in Pietermaritzburg was named after him.

The plan

In Volunteer Camp Orders on 6 and 7 December there was no mention of the proposed Gun Hill operation. In fact, there was every indication of another routinely dull siege day. Dacre Shaw's Squadron of the Natal Carbineers, for example, had just returned from a 24-hour picquet duty, and was looking forward to turning in for the night. The Carbineers were also due to furnish the nightly guard on the commissariat store, and all Volunteer troops, mounted and dismounted, were scheduled to stand to, as usual, at 03.30. Hunter only met with Colonel William Royston, the commandant of the Volunteers, on the afternoon of 7 December to arrange the details of the operation.

The briefing beforehand stipulated that gunfire was to be avoided to secure the element of surprise. This emphasis on stealth was well suited to the colonials, 'many of whom know by sporting experience on the veldt that silence is a virtue' (Pearse, 1900, pp 23-4, 106). The Times of Natal (20 February 1900) suggested another, more personal reason why the Volunteers were an ideal choice for this assignment: 'They [the colonial troops] were the very fellows to entrust with such a job. As smart on the kopjes as the Boer himself, they knew his peculiarities, and what is more, they were simply consumed with the desire to administer to him a special dose of Natal mixture. I believe the Boers would sooner be licked 50 times by Imperial troops than once by Colonials.'

The Gun Hill raid was also an example of the British penchant for utilising colonial troops and scouts only when commanded by British officers. Nevertheless, as Dacre Shaw recalled, everyone 'was hugely delighted at having been selected for the adventure (rather than the regular infantry), the more so as all of us realized the novelty of using (dismounted) horsemen for storming a position' (Dacre Shaw, p 50; Richard Danes, 1901, P 343).

The march to Gun Hill

Estimates of the force's strength vary from 546 to 650, and comprised largely of the Natal Carbineers (200 to 270) and the Border Mounted Rifles (180) as well as 100 men of the Imperial Light Horse. The column moved off from Devon(shire) Post between 21.00 and 23.00 on 7 December, on the Helpmekaar road that skirted the northern slopes of Gun Hill and Lombard's Kop. Even at this late stage, the participants remained, literally and figuratively, 'in the dark'. Sergeant Dick Seed recorded in his diary entry for 7 December: 'Paraded with Volunteers and ILH and marched out of town by the Dundee road. Nobody knew where to or what for. When well on the way it was whispered along the line that everybody was to be as quiet as possible as we were about to try and capture Long Tom' (Diary of Sergeant Dick Seed, Natal Police, 7 December 1899, Siege Museum, Ladysmith). Of course, the presence of the Engineer party, and Hunter himself, no doubt suggested that something special was afoot.

The column was guided to the foot of Gun Hill by scouts from the Corps of Guides. There were also three civilian guides. It was one of the few occasions when the largely unsung work of scouts, both enterprising and risky, was acknowledged at all.

To the top

The ascent of Gun Hill proper, after an approach across a stony plain dotted with dongas and Mimosa trees, was a daunting prospect in the view of Philip Tucker of the ILH, who described the hill as 'a fair terror of a place being some hundreds of yards high, terribly rocky, and shifting gravely soil, and nearly as steep as the side of a house' (Diary of Philip York Tucker, p 14, 7 December 1899, Siege Museum, Ladysmith). An assault force of about 200 men was told off for the attack, while flanking and reserve contingents operated in support. Those remaining in reserve formed up in a semi-circle at the foot of the hill, where they had to lie in the rank grass, struggling to stay awake while officers patrolled the ranks. According to the Natal Witness (6 January 1900), it was the task of a portion of this party, on the western or Bulwana side of Gun Hill, to prevent 'any assistance being rendered by the Boers who were encamped in large numbers at the eastern base of Umbolwan' (See also Breytenbach, 1971, P 439; Times of Natal, 12 December 1899; Dacre Shaw, p 50; and the Ladysmith Siege Diary of Alfred Wingfield, 7 December 1899, Natal CarbineersArchive). It is sometimes difficult to differentiate between the role of the static reserve force and the diversionary party earlier in the day, under command of Colonel Eustace C Knox of the 18th Hussars.

Dick Seed asserts that the flanking forces poured fire in the direction of the Boer camps towards the rear of the hill, but this seems unlikely in view of the clandestine nature of the approach. The following

account of the approach to Gun Hill of the raiding force was published in the Natal Advertiser on 5 January 1900:

'Shortly after 11 o'clock the little column was moving swiftly but silently towards where Lombard's Kop loomed dimly against the deep blue of the sky. The young moon set half-an-hour after the party marched out, but the night was brilliantly starlit. When at a point in line with the Boer gun, the attacking force left the road and made straight for the hill, and the gun. The force advanced in two portions, which met at the base of the hill right below the Boer gun. It was now 2.30 am, and preparations for the attack were at once concluded.'

The final approach over broken ground was difficult, a cause for concern if the men were exposed to Boer fire in daylight. The decisive phase of the attack was launched at 02.45. The Natal Carbineers contingent was on the right flank, opposite Lombard's Nek, with the Imperial Light Horse and others in the centre, and the Border Mounted Rifles on the left.

There were at least 100 Carbineers in the final assault party scrambling up the steep, boulder-strewn 500ft slope just behind General Hunter himself. In the words of Cassell's History of the Boer War (p 44): '[T]hey [the ILH] and the Carbineers went up the hill like cats - noiselessly, and often on all fours.' (See also the letter, Douglas Campbell to his mother, 14 December 1899, in the Greytown Museum). A startled Boer sentry was encountered about halfway up the hill. Popular accounts of the attack, especially by partisan British war correspondents, and in the Natal colonial press, ridiculed the reputedly startled panic of the Boer sentries, with reports of such panicky shouts as 'Schiet, Stephanus, hier kom de verdomde rooineks, schiet, schiet!' [Shoot, Stephanus, here come the cursed red necks, shoot, shoot!], hardly covering the burghers in glory. (Amery, Vol III, p 168; Pennington, p 45; Nevinson, 1900, p 146).

The frantic warnings from such inadequate sentries came too late, and the storming party was close enough to their objectives to rush the posts successfully, under the personal and inspired 'from-the-front' leadership of General Hunter himself. According to J D Kestell, the Boer sentries were duped by the attackers pretending to be burghers from the Modderspruit camp, a ruse employed by the Boers at Caesar's Camp/Platrand on 6 January, but the Gun Hill allegation cannot be confirmed (Macdonald, 1900, p 120, and see Nicholson diary, 7 December 1899, Natal Carbineers Archive; Kestell, 1976 reprint, p 34).

The defence 'crumpled up like tissue-paper' the moment the Boers realised that the assailants were practically at close quarters (Times of Natal, 20 February 1900). The gun-emplacement had been guarded by only sixteen men, with a further 25 in the immediate vicinity, and a laager of 250 men in the rear of the hill.

Once the Boer defenders were alerted during the final phase of the assault, the attackers faced volleys of Mauser fire, and they dropped to the ground for cover and replied with volleys of their own. This tactic was a novel one for the time, when the importance of seeking cover during an attack was not yet widely appreciated. Reaching the summit, in Alfred Wingfield's words, was the 'proudest moment of our lives!' (Wingfield Diary, 7 December 1899).

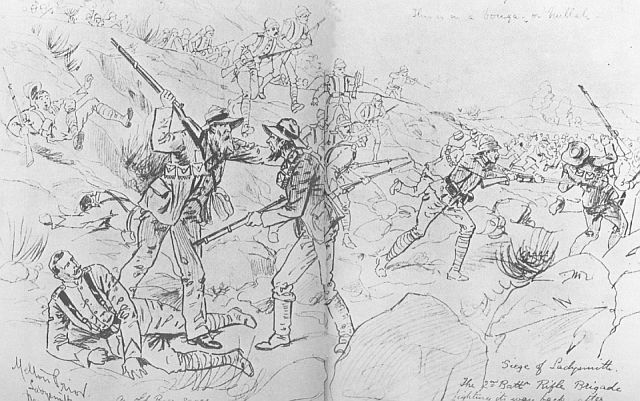

'Fix bayonets!'

The most celebrated incident of the assault, which was the order to fix largely non-existent bayonets during the final phase - thereby exploiting the popular perception of an Achilles' Heel in the Boer makeup, namely a reluctance to engage at close quarters with 'cold steel' (they rejected the bayonet as a barbaric weapon) - was attributed to Colonel A H M Edwards, 5th Dragoon Guards, in command of the Imperial Light Horse contingent on the night. The only troops actually equipped with bayonets were the dozen Royal Engineers responsible for the demolition of the guns. However, the others, by knocking their rifle-butts lightly against stones, created the realistic effect of fixing bayonets. The bayonet order appears to have been the defining moment in the operation. Carbineers RSM Bernard Bowen (letters and papers, Bowen to Cissie Teasdale, 14 December 1899, Witness

The English and colonial popular press ridiculed the apparent Boer fear of the bayonet, and by implication, the close quarters combat that it implied. A party of Boers was reported to have commented to British medical personnel at Ladysmith that they did not regard the use of the bayonet as 'fair', and 'got a fair skrik' when orders to use the feared weapon were issued. The bayonet, the British Army's celebrated 'cold steel', in fact exerted a strong fascination for contemporary observers, demonstrated by several graphic descriptions of this weapon in use during the Anglo-Boer War. A few days after Gun Hill, when the British Rifle Brigade attacked Surprise Hill, several burghers were killed by this dreaded weapon, which, of course, was carried on that occasion: 'A man started up out of the gloom with a low exclamation of surprise, and the next instant there was that dull lunge of the bayonet as the first man on the crest drove it through the breast of the Boer sentinel. "Oh God!", the poor wretch screamed in Dutch as he fell writhing to the ground, clutching with both hands at the weapon that had transfixed him.' (Macdonald, 1900, p116).

On 6 January 1900, Colour-Sergeant Price of the Gordon Highlanders, in another example, on Caesar's Camp, 'sent a bayonet-thrust into the forehead of one Boer with the full force of his strong arm' (Pearse, 1900, p 204; see Danes, 1901, pp 398-9, for further commentary on the bayonet in action on 6 January). In terms of 'cold steel' though, the Colony's own mounted troops were only issued with an all-purpose knife, dubbed the 'Bushman's Friend'. These could be lashed to the barrels of carbines and, according to the Times of Natal (12 December 1899), this was done on this occasion. (See also Dacre Shaw, p 50, and Brown, nd, pp 165-6).

Also worthy of special mention was the leadership of Major-General Hunter. During the AngloBoer War in Natal it was not uncommon for British flag officers to risk their lives in such assaults, as the deaths in action of Major-General Sir William Penn Symons at Talana on 22 October 1899, and Major-General E R P Woodgate at Spioenkop on 24 January 1900, testify. Hunter's energetic leadership at Gun Hill and the fact that his name was chosen as the password for the night, gave rise to the following amusing story in ILH folklore: 'During the early stages of the attack Sergeant (later Lieutenant) Finch-Smith of the ILH was annoyed by someone he mistook for one of his own men who would not keep his position. His suspicions aroused, he hissed at the man, "Keep your place". When the man took no notice, the sergeant grabbed him by the throat and said, "Who are you?" "Oh, I'm Hunter", was the reply in a nearly strangled voice. "I know damn well that Hunter is the password, but who the hell are you?" To the sergeant's consternation the reply came, 'I'm Hunter, don't you know, General Hunter." , (Hunter, 1996, p 131; and see George Thompson Reminiscences and Diary, letters, p 5, 21 December 1899, William Cullen Library).

The demolition of the guns

The focus of the daring sortie, the demolition of the artillery pieces on Gun Hill by a party of engineers, was completed in about ten minutes. 'It was [commented Donald Macdonald] a lesson in military expedition then to see Engineers going to work at gun destruction. Some of them whipped out the breech-block; others ran a charge of gun-cotton halfway down, plugged the muzzle and the breech, after first chipping away part of the screw, so that it could not be used again. Then they ran a necklace of gun-cotton around the outside of the barrel, and all was ready for Long Tom's funeral' (Macdonald, 1900, p 106).

The sophistication of the emplacement, which included 30ft thick protective walls, came as another unwelcome realisation by the British of their underestimation of the Boers' ability to adapt to the demands of European military science. The gun 'had been beautifully set on a traverse of solid masonry. It was mounted on huge iron wheels, and a little railway-line had been laid down to run it up to the the firing position. Over it was a thick bombproof arch, and a huge stack of shells lay round about ready for use' (Macdonald, 1900, p 106). The defenders of Ladysmith had cause once again to wonder at the Boers' underrated skills with artillery when they clambered up Bulwana on 1 March 1900 to the then recently abandoned gun position for the Long Tom stationed there.

Once all the charges were in place, the detonator was activated: There was a dull roar ... [and] ... the whole mountain flamed up with a flash of light' (Macdonald, 1900, p 107). Ironically, considering the origins of the ILH in the ranks of the Johannesburg Uitlanders, the Boers had nicknamed this gun, 'The Franchise', tempting these Uitlanders to take the 'franchise' for free, which, of course, is exactly what they did.

The aftermath of the raid

The overall significance of the operation was minimal, if the entry in Carbineer W S Warwick's diary (Natal Carbineers Archive) is anything to go by: 'Sent out at 10pm to capture boer gun at Lombard's cop [sic] great success, no one hurt, gun blown up, retired back to camp at 5.30[am]'. Although the breechblock had been removed and the muzzle damaged - 'Combustion of the bowels had placed the poor fellow beyond all aid', in the words of Donald Macdonald (1900, p 107) - the gun was, in fact, removed to the railway workshops, Pretoria, for repairs, and was returned to action outside Kimberley by 7 February 1900, albeit somewhat stunted in length, and nicknamed 'Die Jood' (The Jew'). A civilian diarist of that siege, Winifred Heberden, recorded the consternation caused on that morning by the unexpected arrival in Kimberley of the huge Creusot shells.

As early as 15 December 1899, De Express en Oranjevrijstaatsche Advertentieblad announced that 'Long Tom gaat Pretoria toe voor herstel. ('Long Tom goes to Pretoria for repairs.') (See also Changuion, 2001, P 55 and Grobler, 1984, pp 8-9). All the Boer siege guns, including the Gun Hill piece, were destroyed during September and October 1900 and April 1901 in the then eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga Province) to prevent them falling into British hands. It is ironic, considering its trials, that the durable Gun Hill Long Tom, designated L T 4, was the last to finally fall in action, on 30 April 1901 in the vicinity of Lydenburg.

The Gun Hill raid was thought to be the first time in British military history that mounted infantry had stormed guns. Night attacks were also a rarity in the Anglo-Boer War, including the sieges, where an attack such as Gun Hill showcased their utility. The propaganda value and impact on morale was considerable, especially for the Natal colonial forces and civilians. 'Friday the 8th', commented James Bayley of the Ladysmith Town Guard in his diary (Siege Museum, Ladysmith), was 'somewhat of a red letter day of the siege' (see also Smith, 1937, p 15, for similar sentiments). The Long Tom breech-block, for example, was carried back in triumph by troopers of the Imperial Light Horse, to find a home as a much-admired vase in that unit's Officers' Mess. The rangefinder and ramrod were also removed. It was also recorded that the attackers scratched their names on the damaged gun.

The Cape Argus Weekly Edition of 10 January 1900 enthused: 'The attack, which was successful beyond expectation, reflects the utmost credit upon the volunteers, who have all along played so prominent a part in this campaign'. Minor forays from besieged Mafeking, on the other side of the country, had a similarly positive effect on morale. Eyewitnesses from nearby Intombi Camp and Ladysmith were also suitably impressed: 'Then suddenly a flash leapt up from [Gun Hill's] crest followed some seconds after by the roar of an explosion, quickly followed by another, and this gave us the welcome tidings that our vicious teasers were no more'. (Watkins-Pitchford, 1964, pp 32-3 and Pennington, p 44. Another who awoke in the early hours to the sound of gunfire and explosions was Nurse Joan Charleson, whose experience is recorded in the Weekend Advertiser, 1 March 1930.)

Newspaper and popular accounts were replete with praise. The Natal Witness in Pietermaritzburg (6 January 1900) described it as a 'dashing night attack' and similar sentiments were expressed in the Cape Argus Weekly Edition (10 January 1900). R J McHugh (1900, P 109) commented: 'Thus far it is the most brilliant incident of the siege, and it was carried out without a hitch.' Pearse (1900, p111 ) recorded that the Natal Carbineers 'deserve full credit for an important share in the night's success'. Nevinson (1900, p 148) wrote that the main difficulty of the retirement of the colonial force was to persuade the men to

leave the scene of their adventure: 'The Carbineers especially kept crowding round the old gun like children in their excitement.' Ladysmith's own siege newspaper, the Bombshell (1 January 1900) could not resist this opportunity to rub salt in the Boer wounds, and published the following satirical piece, mimicking the Boer indignation at the attack:

'£1 000 reward. Whereas on the night of the 8th December last some evil disposed person or persons did wilfully destroy and carry away certain heavy guns from Lombard's Kop, Natal. The said guns being the property of the ZAR, anyone giving information that will lead to the recovery of the guns, and to the punishment of the offenders will be rewarded as above.'

The Gun Hill raiding force arrived back in Ladysmith by 03.30 on Friday, 8 December, to the enthusiastic cheers of all the regiments it passed. It had been 'a memorable day in the history of our Volunteers: a deed of daring and success that will want a lot of beating in the war' (Pennington, p 43; and see Wingfield, 7 and 8 December 1899). The stirring writing of the Daily Telegraph correspondent, RJ McHugh (1900, P 113, and see p 115), was typical: 'The manner in which they accomplished this duty will be an honour ever to be remembered, and the story of it will be told in Natal for many a generation.' According to Steevens in the Natal Carbineers History Centre (Woods Newspaper Cuttings, nd), it 'had all the requisites of successful night work - absolute secrecy, picked men, a daring and cool-headed leader, accomplished guides, silence, celerity and luck'. It was, in the words of war correspondent Donald Macdonald, 'a feat which cheered our drooping spirits, and won in a single act a reputation for the volunteers of Natal' (Macdonald, 1999 reprint, p 118).

A diversionary British operation to seize Limit Hill, which achieved mixed success, was largely ignored amidst the blaze of publicity surrounding Gun Hill. The point of particular interest to emerge from this sub-operation was that the British troops involved resorted to type in terms of how not to engage the Boers when they delayed their return to da'ylight hours and consequently became easy targets for the burghers.

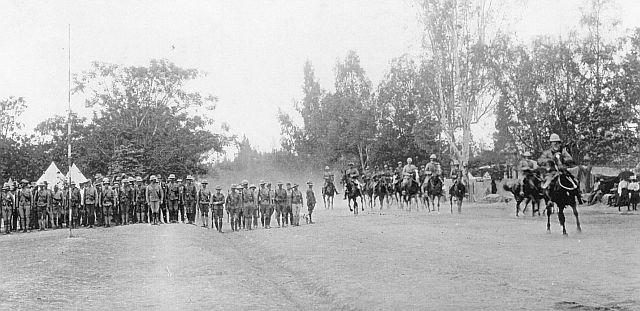

General White's review of troops

At noon on 8 December, the Volunteers formed up on open ground adjoining the Volunteer camp for a congratulatory address by the garrison commander, Sir George White, in which the credit owed to them by both the Colony and the Empire was given special emphasis. There was also a large turnout of civilian spectators. White also visited each of the Carbineer, Guides and Imperial Light Horse camps in turn. On the same afternoon White telegraphed a brief report to Pietermaritzburg on the outcome of the sensational expedition: 'Last night I sent out General Hunter with 500 Natal Volunteers under Royston, and 100 Imperial Light Horse under Edwards, to surprise Gun Hill. The enterprise was admirably carried out and was entirely successful, the hill being captured and a sixinch gun and a four-point-seven howitzer destroyed' (Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository, CSO 2609, transcript telegrams, White to GOC Lines of Communication, Pietermaritzburg, 8 December 1899; Natal Witness, 11 December 1899).

In an editorial on 12 December 1899, the Natal Witness commented that the 'words of appreciation and encouragement addressed by General White to the Volunteers were timely and well chosen. It is gratifying to the colonists to learn in such unmistakable terms that the services of our Volunteers are thoroughly appreciated by officers of the Imperial troops.' (See also Natal Witness, 3 January 1900 for further sentiment in a similar vein. News of the attack was also read out to troops of Buller's Arrry at Sunday church-parade on 10 December, according to the notebook diary of R C Alexander in the UNISA Archives). The Carbineers also received a congratulatory letter from the Gordon Highlanders, who subsequently fancied an attempt at the most ambitious venture of all, an attack on the Bulwana emplacements. The attempt was never made. The Natal Witness (3 January 1900) went as far as to say that the Carbineers, 'after their brilliant success of Gun Hill were regarded by regulars and civilians alike as one of the best, bravest, and most reliable corps in camp. Gun Hill immensely increased the prestige of Natal's Volunteers' (See also Macdonald, 1900, p121).

The Surprise Hill sortie

Popular sentiment aside, the dramatic nocturnal action was one of the few positive pieces of war news to have reached the Natal press for some time. The British regulars, for their part, may have basked in the reflected glory of the Gun Hill expedition, but they were indignant at their exclusion from the successful foray, and welcomed the opportunity on 11 December to reap some glory for themselves with a similar, but more ambitious, raid on Surprise Hill/Vaalkop, utilising mainly the Rifle Brigade. The subsequent raid, although also successful, did not proceed as smoothly, and was prosecuted with a high cost in lives. In distant Kimberley, too, a similar attack on 26 November on fortified Boer guns had proven costly.

The casualty roll for Surprise Hill presents an important contrast between the two expeditions that were very similar in conception. For Ithe British, the fourteen killed or mortally wounded, and fifty more wounded, was regarded as a modest price to pay for the opportunity 'to resume their proper function of attack' (McHugh, 1900, p 128; and see Amery (ed), Vol III, p 172 and Churcher, 1984, p 55). The positive effects on propaganda and morale notwithstanding, adverse reaction in colonial circles to Surprise Hill and Colenso, on the other hand, points to concern about the Volunteers becoming involved in British operations that incurred similarly heavy casualties.

The British could at least claim Surprise Hill as a nominal success, but such ventures could go disastrously wrong. During the siege of Mafeking, for example, the major raid by the besieged forces on the surrounding Boers, against Game Tree Fort, among others, was a costly failure, incurring, for that garrison, its heaviest casualties in three months of siege. It is perhaps surprising to read the account of the civilian surgeon in Ladysmith, James Alexander Kay, commenting in rather harsh tones on the Surprise Hill casualties: 'However, [he wrote on 12 December 1899, quoted in May, 1970, p 41] we must break eggs when we make omelettes.'

The severe casualties suffered in the British operation at Surprise Hill led a correspondent to the Natal Witness to question the deployment of colonial mounted infantry as infantry in a high-risk operation such as a night attack on a prepared position, despite the success of the attack on Gun Hill. Shortly after Gun Hill, on 15 December 1899, the Volunteers with Buller's Relief Column were themselves deployed as infantry at the battle of Colenso, eliciting similar protest from commentators in Natal. Within a few days of the Gun Hill operation, Colonel Royston also collected together a column of Volunteers for the proposed demolition of the Wasbank railway bridge. This operation was, however, aborted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archival sources

Campbell, Douglas, letter to his mother, 14 December 1899 (Greytown Museum).

CSO 2609, transcript telegrams, White to GOC Lines of Communication, Pietermaritzburg, 8 December 1899 (Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository).

Diary, Alexander, R C, notebook diary (UNISA Archives, Pretoria).

Diary, Bayley, James, Ladysmith Town Guard (Siege Museum, Ladysmith).

Diary, Gill, Lieutenant D Howard, 21 st Battery, Royal Field Artillery, Transvaal War 1899-1900 (UNISAArchives, Pretoria).

Diary, Nicholson (Natal Carbineers Archive).

Diary, Seed, Sergeant Dick, Natal Police (Siege Museum, Ladysmith).

Diary, Thompson, George, Reminiscences and Diary, letters (William Cullen Library).

Diary, Tucker, Philip York (Siege Museum, Ladysmith).

Diary, Warwick notebook-diary (Natal Carbineers Archive).

Diary, 'Ladysmith Siege Diary of Alfred Wingfield, No 4 ('D') Squadron, Natal Carbineers, November 1899-March 1900', Typescript (Natal Carbineers Archive).

Leyds 1043, CD 458, White to Chief-of-Staff, 23 March 1900. (National Archives Repository [NAR].

Natal Carbineers History Centre (Steevens), 'Woods Newspaper Cuttings', nd.

Pennington, Reverend G E, 'Anglo-Afrikander War 1899-1900', (Siege Museum, Ladysmith).

Shaw, Dacre, 'Trooper, Natal Carbineers', (Natal Carbineers Archive).

Newspapers, etc.

Cape Argus Weekly Edition, 10 January 1900.

De Express en Oranjevrijstaatsche Advertentieblad, 15 December 1899.

Ladysmith Bombshell, 1 January 1900. Natal Advertiser, 5 January 1900. Natal Mercury, 9 December 1899.

Natal Witness, December 1899, January 1900.

Times of Natal, 12 December 1899, 20 February 1900.

Published sources

Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol III (London, Sampson Low, Marston & Co, 1905).

Bowen-Teasdale Letters and Papers, Bowen to Cissie Teasdale, 14 December 1899 in the Witness, 29 June 2006.

Breytenbach, J H, Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, II (Pretoria, Die Staatsdrukker, 1971).

Brown, Harold, War With the Boers: An Account of the Past and Present Troubles with the South African Republics, Vol II (London, H Virtue and Co, nd).

Changuion, Louis, Silence of the Guns: The History of the Long Toms of the Anglo-Boer War (Pretoria, Protea Book House, 2001).

Charleson, Joan, 'Thirty Years Ago' in Weekend Advertiser, 1 March 1930.

Churcher, D W, From Alexandria to Ladysmith With the 87th (York, Boer War Books, 1984).

Danes, Richard, Cassell's History of the Boer War 1899-1901 (London, Cassell and Co, 1901).

Grobler, DC, Die Long Tom Kanonne (Auckland park, Federasie van Rapportryerskorpse, 1984).

Hunter, Archie, Kitchener's Sword-Arm: The Life and Campaigns of General Sir Archibald Hunter (Staplehurst, Spellmount Publishers, 1996).

Kay, Dr James Alexander, 12 December 1899, quoted in John Henry May, Music of the Guns: Based on Two Journals of the Boer War (London, Jarrolds, 1970).

Kestell, J D, Through Shot and Flame (London, Methuen & Co, 1903, reprint: Johannesburg, Africana Book Society, 1976).

Macdonald, Donald, How We Kept the Flag Flying, The Story of the Siege of Ladysmith (London, Ward, Lock & Co, 1900; reprint: Weltrevreden Park, Covos Books, 1999).

McHugh, R J, The Siege of Ladysmith (London, George Bell & Sons, 1900).

Nevinson, H W, Ladysmith: The Diary of a Siege (London, Methuen & Co, 1900).

Pearse, H H S, Four Months Besieged: The Story of Ladysmith (London, Macmillan and Co, 1900).

Smith, W H, Reminiscences of the Siege of Ladysmith (Ladysmith, CW Budge & Co, 1937).

Watkins-Pitchford, H, Besieged in Ladysmith (Pietermaritzburg, Shuter and Shooter, 1964).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org