The South African

The South African

('Last night at approximately 02.30 our position was unexpectedly assaulted by the enemy ... 25 men and officers held out as long as possible before being compelled to flee in the face of superior numbers.')

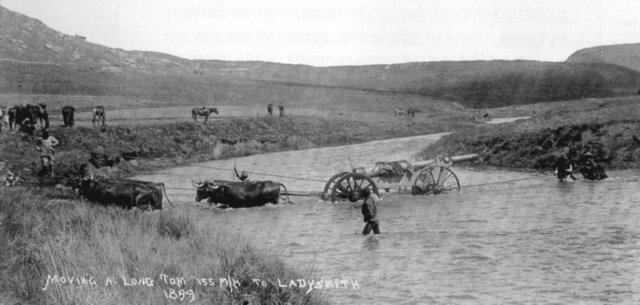

The markedly lax security in standing encampments, a feature of the Boer siege-ring during the Siege of Ladysmith, became a bone of contention in the commando ranks, especially in the wake of the attack on Gun Hill on the night of 7 to 8 December 1899. The burghers outside Ladysmith were vulnerable by early December 1899 as complacency and inefficiency in the siege laagers had replaced the initiative and drive associated with their war of movement. They were as unsuited to a static war as were the Natal Volunteers. Nevertheless, the Boers should have placed special emphasis on the security of the Creusots, considering that the Boer leadership were particularly concerned, for propaganda reasons, that these prestigious guns not fall into the hands of the enemy. Instead, as J H Breytenbach (Vol II, 1971, P 437) commented ominously with regard to the critical issue of sentries on the gun positions: 'Daar is wel wagte uitgesit - bloot as 'n saak van roetine maar die wagte het gewoonlik le en slaap en van 'n effektiewe wagdiens was daar dus geen sprake nie.' (There were indeed sentries posted - simply as a matter of routine - but these sentries usually lay and slept, and there was no question of an effective watch.')

The weaknesses evident in the Boer ranks did not escape the British, who kept an eye on their besiegers. Donald Macdonald painted a crudely effective, if exaggerated, picture of Boer inadequacy at Gun Hill on the night of 7 to 8 December 1899, in his description of the porous, almost non-existent, sentry cordon around this important gun-site, suggesting mockingly that it had been a case of letting the enemy past first and then challenging him (Macdonald, 1999 reprint, p 105; and see Fransjohan Pretorius, 'Life on Commando' in Warwick, 1980, pp 114-5, for a good potted description of sentry duty as it was meant to be performed). The laxity of the sentry cordon on this occasion was probably also influenced by the frequent false alarms confronting Boer sentries that had bred a 'cry wolf' cynicism and disregard. Boer reports betrayed a stunned and dismayed reaction to the raid among the burghers. Take the Gedenkboek van den Oorlog in Zuid-Afrika (1904, pp 197 -8) for example:

It was the unfortunate officer in command of the Boer artillery on Lombard's Kop, Major PE Erasmus, who had sought fit to station only 25 men at the guns, who had the unenviable duty of informing President Kruger of the disaster, in the process of which he diverted most of the blame onto the burghers whose duty it had been to secure the Staatsartillerie positions. It was little wonder that the Boers admired the skill and judgement displayed by the attackers at Gun Hill ('a devilish sporting deed', one was recorded as saying [Natal Witness, 28 February 1910; and see Siege Museum, Ladysmith, Reuter's cablegrams, 10 December 1899]) but

they deplored the low standard of burgher discipline and vigilance which was brought into sharp focus. The person to make this observation most eloquently and forcefully was Colonel (Comte) Georges de Villebois-Mareuil, the gifted French officer serving with the Boer forces, who had warned about the absence of outposts, sentries and supporting forces. Ordinarily he, too, would have been impressed with the British- Colonial exploit. In fact, consternation ensued in Boer political and military circles, and on 8 and 9 December the telegraph lines between Modderspruit (where the Boer 'hoofdlaager' at Ladysmith was situated), Volksrust, where Commandant General Piet Joubert lay ill in bed, and Pretoria, hummed with furious accusations and recriminations. The first of these heated telegrams, from the 'hoofdlaager' to Pretoria, began as follows:

'Een hewige kanon en maxim vuur vindt nou plaats. Volgens rapport trek de vyand van Ladysmith ongeveer half-drie en heefdt een van ons groot kanonen genomen. Verschillende commandos hubben posities genomen ongeveer 800 treden van kantoor af en wacht op aanval van vyand - zal u later meer vuldig berichten.' ('A heavy exchange of cannon and Maxim fire is underway. According to reports the

enemy left Ladysmith at approximately 02.30 and captured one of our big cannons. Various commandos are in positions approximately 800 metres away and await an attack by the enemy - will inform you

later in more detail.' [NAR, Leyds 712f, telegram, Joubert to Botha, 9 December 1899]).

In a Reuter's cablegram of 12 December, the burghers at Ladysmith offered the rather weak excuse that the attack could not have succeeded had a search-light been situated on Lombard's Kop. Possibly the least impressed of all in the Boer ranks was the aged, weary, and sick Joubert himself. By the morning of 9 December, the patriarchal Joubert had reflected sufficiently on the incident and its implications to formulate a cutting and grimly sarcastic telegram to Louis Botha at Colenso. He opened by announcing that the siege commandos had been presented with 'een ernstige les en waarschuwing' ('a serious lesson and warning'), suggesting that the complacent burghers were in the habit of retiring in the evening as if they were at home in bed! As if reprimanding errant children, he reminded Botha of his own precautions when on commando: 'Zoolang ik op commando gezond ben slaap ik met myn patroon band om myn lyf en myn geweer in myn arm, en dan des morgens 2 uur voor dagstaat ook myn paard gereed.' ('While I am on commando I sleep with my cartridge-belt around my body and my gun in my arm, and also awake at 02.00 to prepare my horse') (NAR, Leyds 712f, telegram, Joubert to Botha, 9 December 1899).

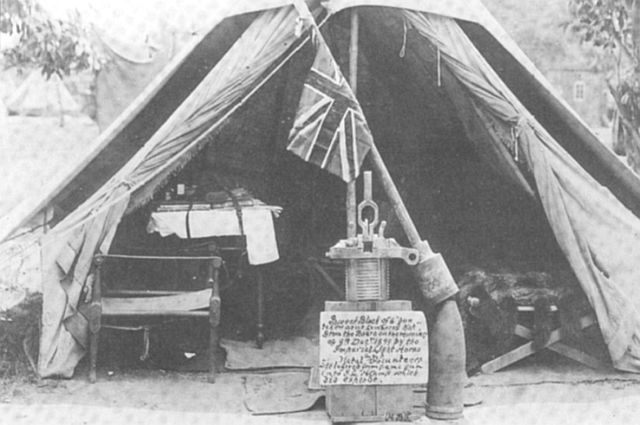

] However, despite this entire furore surrounding the raid, another telegram, possibly intended for public consumption, and found in Vryheid when British troops occupied that Transvaal town in September 1900, paints a very different picture, considerably down playing the impact and significance of the operation. It reported on 8 December that, '[i]t appears, from [a] report, that the enemy made a surprise attack last night [7 December] on Lombard's Kop, Ladysmith, one of our large cannon and a howitzer being damaged, and a small hand-maxim carried off by them. The cannon, however, will be repaired as soon as possible. The kop (hill) remained in our possession.' (Dutch Official Telegrams, p 23, 8 December 1899).

An inquiry, conducted by the Transvaal State Attorney, Jan Smuts, was duly convened in February 1900, operational demands having precluded an earlier date. Erasmus requested to be placed under voluntary arrest, and all officers on duty at Gun Hill on the night in question were reduced to the ranks. Some time later the Boer leadership, who had been shaken out of their complacency, also belatedly sought to inject some enthusiasm into the burghers, and venom into their siege, by offering incentives or 'rewards' for the destruction or capture of British guns. Security around gun emplacements was also improved, and those in extreme forward positions on heights such as Gun Hill were to be withdrawn at night to more easily defended positions. According to the diary of D Howard Gill (31 December 1899), the Boers since the attack 'have made all their positions frightfully strong, with sangars, wire entanglements, brushwood abattis and probably landmines'.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Breytenbach, J H, Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog 1899-1902, Volume II (Pretoria, Die Staatsdrukker, 1971).

Gedenkboek van den Oorlog in Zuid-Afrika (Amsterdam-Kaapstad, Hollandsch-Afrikaansche Uitgewers Maatschappij, 1904).

Macdonald, Donald, How We Kept the Flag Flying: The Story of the Siege of Ladysmith (London, Ward, Lock & Co, 1900 [Reprint edition, Weltrevreden Park, Covos Books, 1999]).

Natal Witness, 28 February 1910.

National Archives Repository (NAR): Leyds 712e, war telegrams, Major Erasmus to Joubert, Volksrust, 4.30am, 8 December 1899, and telegram, Joubert to Botha, 9 December 1899.

Siege Museum, Ladysmith: Reuter's cablegrams, 10 December 1899, and Dutch Official Telegrams.

UNISA Archives: Gill diary, 31 December 1899.

Warwick, Peter (ed), The South African War: The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 (London, Longman, 1980).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org