The South African

The South African

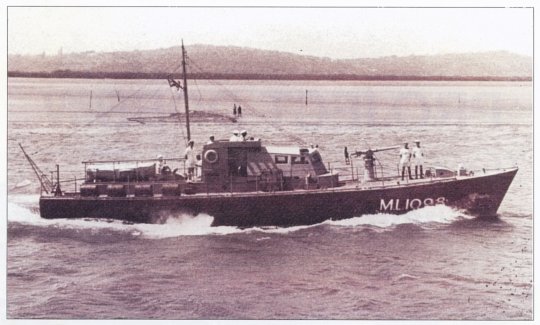

This is the tale of the South African Navy's minor warship P1558, a fast patrol boat that proved to be one of the more spectacular failures of naval planning during the 1970s. To place the story in perspective, this account begins with another ship completely, the Harbour Defence Motor Launch 1204, or HDML 1204 for short.

One of a class of South-African built wooden motor launches

used by the South African navy until the mid-1970s, when HDML 1204,

the last survivor of the class, and all remaining spares, were sold off.

HDML 1204 was the last survivor of a class of eleven wooden launches built in various South African boat-building centres in 1943. This class did sterling service in the Second World War and afterwards, but all except HDML 1204 were gone by 1971. She was serving as a range clearance vessel for the gunnery school and was based in Simon's Town. However, on 12 March 1971 she was transferred to the Military Academy in Saldanha Bay as a training ship. She was ideal for this purpose as she had accommodation for two officers and twelve ratings, was 21 ,3m (75 ft) long and, at ten knots, could not really get into much trouble.

Unofficially named Disa, after the Military Academy's crest, she served the Academy well until 1974, when her keel and bottom planking became waterlogged and she was in imminent danger of sinking at her moorings. She was put up for disposal and was sold for the princely sum of R1 000 'as is, together with all relevant spares' to a Mr Charles Bates. This generated a lot of controversy in the press as 'all the relevant spares' at the Naval Stores Depot at SAS Wingfield included all the remaining spares for the entire class. Among these were spare diesel engines and even the ship's bell clock in the Academy classroom, which a stores officer had placed on the ship's inventory by mistake and which Mr Bates insisted on receiving. This left the Military Academy with no seagoing training ship.

Before being handed over to the South African Navy,

the completed P1558 went through acceptance trials.

Malawi

The 1970s were, of course, a period of severe international isolation for South Africa as a result of her 'Apartheid' policies. The only black African country, apart from her immediate neighbours, which maintained diplomatic relations with her was Malawi under the leadership of Dr Hastings Banda. In fact, a large part of the funding for his new capital of Lilongwe came from South Africa. As a result of this friendship, Malawi felt threatened by her neighbours and, as a large part of her frontier is formed by the waters of Lake Malawi, she decided to establish a navy with South African help.

A number of military personnel were then drafted into this new navy and sent down to SAS Flamingo, the then crash boat (Air/Sea Rescue) station at Langebaan, near Saldanha. There they were to be trained by Cdr Vic Nielson, who later became South Africa's Naval Attache in Malawi. The group arrived carrying a varnished set of ship's nameboards with the name 'Simba' etched thereon in gold paint, but where was the Simba? She was certainly not in Langebaan. She was, in fact, in Durban.

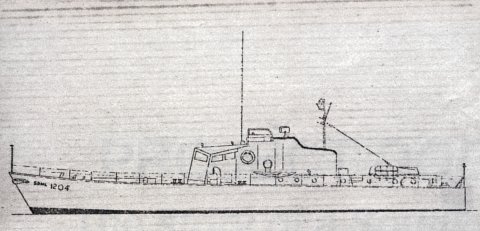

The Malawi Navy had engaged Dorman Long, van der Bijl Corporation at Bay Head in Durban to design and build their ship. Dorman Long had obtained the plans of a very successful 33-metre patrol boat from Brooke Marine Ltd of Lowestoft in the United Kingdom and had re-designed the ship for service on Lake Malawi. They reduced its length to 27 metres and refined the design to come up with a ship that would be inexpensive to build and would be simple to maintain with a minimum of skilled back-up. She would be all-welded mild steel construction with a round bilge hull, and not flat-bottomed like most fast craft; would have a beam (width) of 5,33 metres and a shallow draft of only 1,7 metres.

A sketch of HDML 1204, last survivor of its class.

The ship was laid down in 1974 and completed in 1976 and looked a lovely little ship. Of 80 tons, she had spacious and air-conditioned accommodation for her crew of fifteen. She had a full range of navigational equipment and twin B&W Marine engines which would push her along at 20 knots, quite fast enough for lake work. She was an attractive and powerful-looking ship with a pronounced wave-deflecting knuckle forrard and, once she was armed with a hand-operated 40mm Bofors gun forrard and a single 20mm mounting aft, would have been a formidable warship on the Lake.

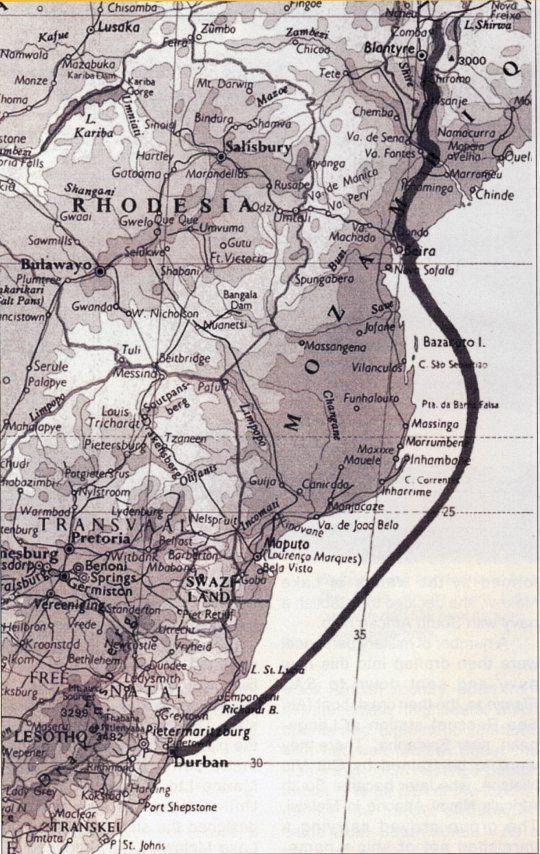

Getting this 80-ton ship to Malawi would be an adventure reminiscent of similar efforts in the First World War. She was to be steamed to Beira, taken up the River Pungue, transferred by land to the Shire River and then sailed down to the Lake to be based at Monkey Bay on the southern end of Lake Malawi.

Alas for the best-laid plans of men ... A reconnaissance of the proposed river route carried out in a barge by Mr Willem Venter of ARMSCOR and Cdre Ted Jupp of the South African Navy (SAN) proved it to be impracticable and, before she could be completed, the Flower Revolution in Portugal and subsequent civil war in Mozambique further complicated the problem. With no means of delivery, in 1975 she was taken over by the South African Navy as Patrol Boat 1558. As P58, she was left to languish in reserve at Bay Head and her disconsolate crew at Langebaan returned home to Malawi.

This map shows the proposed route by which the patrol boat was to be delivered to the Malawian Navy.

As fate would have it, at this time the South African Naval Staff Course No 7 was in Durban, visiting the naval installations there, among them the shipbuilding facilities at Dorman Long. While being shown around, the party was taken aboard P58, where the executive showing the group around remarked that they were now stuck with this white elephant, which was completely surplus to the SA Navy's requirements. Among the group of students was a certain Commander Little, based at the Military Academy and whose training ship, HDML 1204, had just been disposed of. 'A pity', said he, 'the Academy could probably use her as a training ship'.

A new training ship

Two days before Christmas 1975, when Cdr Little was back at the Academy, his telephone rang. Did he really want P58? His answer in the affirmative stirred P58's completion and trials and, in January 1976, she was officially completed and taken over by the SA Navy, which stored her up and berthed her at Salisbury Island to await the crew for collection.

SAS Saldanha sent one representative, Cdr W J de Lange, to act as second in command and to get to know the boat, so that they too could use it. The Academy, in its usual inimitable fashion, sent along its version of a deck crew - one nautical science lecturer, a physics lecturer, a sports officer, four midshipmen, a barber and an army cook. The latter two contingents were sent up in the Orange Express, via a scenic tour of the Karoo and Natal, joining up with the others in Durban.

The weather in Durban was perfect on the day the crew arrived - hot and typically humid - with the sea like a mirror. For two days they laboured at getting ready for sea by taking on bunkers, rigging awnings to keep the blazing sun off the steel sides of the ship, doing engine trials and taking on victuals. Note that the writer refers to her as a 'ship' rather than 'boat', for the new acquisition was in every respect a ship. Twenty-seven metres long and built of steel, she was built like a ship, even to the funnel, and it was as 'the ship' that the crew now referred to her.

Sailing day dawned cold, rainy and blustery. The ship was due to sail at first light and, as the first grey tinges lit the sky, the crew cast off and the ship backed out into the harbour. On the quay to see her go was a solitary oil-skinned figure, Cdr Matt Heyns, who, as Officer Commanding Salisbury Island considered it his duty to be there when she sailed. There was a vicious sea and swell running across the bar and as soon as the ship rounded the breakwater, the crew found themselves rolling and plunging horrifyingly. Wave after wave thundered onto the foredeck and up against the bridge windows. Rain poured down in torrents. Water entered the ship through the spurling pipe, the ventilation, the air-conditioning and the engine room intakes. To close the openings meant to stifle; to leave them open meant being flooded out. From the enclosed bridge nothing was visible at all - it was like standing in an elevator moving rapidly up and down under a shower!

The situation aboard was rapidly becoming chaotic. With all the water coming in everywhere, it was literally raining in the engine room and, as the crew were unable to see the fo'c'sle of the ship, Cdr Little decided to return to Durban. Watching the behaviour of the ship very carefully, the crew turned her around and began a swooping, surfing ride, with the sea behind her. At that moment Cdr Little glanced up and found that they were on a collision course with a tanker. To turn once again head-to-sea was dangerous, so they kept on going across his bow, thus forcing him to give way to port. The writer has often wondered since then what his opinion of the SA Navy was just at that time.

Back alongside, the crew mopped up and had a postmortem. On the debit side, P58 had been forced back after only twenty minutes. On the credit side, she had been thoroughly tested in heavy weather. Cdr Little and the crew now knew her weaknesses and could guard against them. More importantly, the crew had performed well and confidently sailed again the next day at noon.

It had stopped raining and blowing, but the swell had to be seen to be believed. Nothing daunted, P58 once again rounded the breakwater and set off down the coast. This time, the crew took it slowly and carefully and the absence of rain made all the difference. At a steady four knots, the ship had progressed as far as Reunion and the swell was easing off, when, without warning, the steering jammed with the rudder at 30° to starboard.

Midshipmen at work

With just this eventuality in mind, the Academy's sports officer, Lt Cdr John Page, who was acting as first lieutenant, had drilled the crew on emergency steering procedure. What they did not know, however, was that the printed instructions, as supplied by the makers, bore little or no resemblance to the actual sequence of operations needed to engage the emergency steering. Nothing appeared to be of any use in restoring the steering and, until they got the emergency steering operations, the rudder stayed locked over to starboard. Every time the crew tried to move, the ship would go around in crazy circles and if she lay still she fell into the trough of the waves broadside on. At one time the crew recorded a 42° roll, which scared the living daylights out of quite a few of them. Eventually, by trial and error, they got the emergency steering operational and ran back to Durban for repairs.

Leaving a skeleton crew of engineers behind, the remainder of the crew returned to Cape Town on the Orange Express, with tails between their legs, there having to face the friendly gibes and insults of their friends. However, without exception, the whole crew volunteered to go back again to try and fetch the ship the following fortnight. This was not possible, however, as, learning from experience, the number of deck crew was reduced and the engine crew increased. The modified crew was flown up again in the first week of March by SAAF Dakota, to make a 'do or die' effort.

This time the odds were on their side as the breathing space had been used by Durban Naval Command to carry out exhaustive tests and modifications. When the crew arrived at Durban, they found their ship lying alongside with engines running and ready to go.

Two hours after arriving in Durban, the crew set off again by sea. Once again the sea was rough and once again it was raining cats and dogs, but doggedly they held on at a steady five knots. As they progressed away from the land, the swell eased. The crew had SAS Reijger in company and although she left them behind in the beginning, they slowly began to gather speed until, at nightfall, they were going eleven knots and abeam of her. By daylight the next day the weather had changed and was blowing strongly from behind and the crew found themselves throttled back to 'dead slow ahead' just to keep back to SAS Reijger. This was clearly ridiculous so, after saying 'goodbye' to her, the little ship went up to 'full ahead' for home.

'Full ahead' in the heavily laden state she was then meant a mere seventeen knots with the current behind her, so it was not until 22.00 that evening that she arrived off Port Elizabeth. This was a most interesting arrival, being a Tuesday night coinciding with a Citizen Force parade at SAS Donkin and the little ship was scheduled to act as an enemy infiltrator that they had to prevent effecting a boat landing on the beach.

The crew darkened ship and came stealing in toward Deal Light with all hands on lookout duties, as they endeavoured to close the beach as rapidly as possible. To stop them doing this, a trap had been set by the seaward defence boat, SAS Oosterland, which, also unlit, was lying in hiding off St Croix island and watching for the 'enemy' on radar.

However, P58 had a secret weapon system, in the form of excellent radar manned by Major P de Villiers and his trusty HP-65 computer, so that as SAS Oosterland rushed down to intercept her, she was able to keep track of her and use her superior speed and manoeuvrability to avoid her. Somehow or other she could just not shake the SAS Oosterland off so P58 'surrendered' and, after being boarded by a fiercely armed and tin-hatted bunch of National Servicemen, the crew were taken in to Port Elizabeth under guard. It was only at the 'wash-up' later that night at SAS Donkin that the crew found they had brought in the Army as well and P58's every move was being watched from mobile radar stations ashore!

To Saldanha Bay ...

Leaving Port Elizabeth the next day, once again in company with SAS Reijger (whom she outran in the first half hour and did not see again for the rest of the voyage), P58 had an uneventful but bumpy passage around to Saldanha. The opportunity was taken to clean her up as much as possible while lying there until, at 4 o'clock on Friday, 12 March, the crew entered on the final leg of the voyage by steaming across the Bay to SAS Flamingo at Langebaan. As she steamed up the channel there, with her hooter blasting, P58 was welcomed by a salvo of Verey pistol flares and the enthusiasm of a large group of VIPs.

Alongside at Langebaan, P1558 is ready for christening after sailing from Durban.

There to meet the crew when they came alongside were their own Officer Commanding, the OCs of the local units, the Mayor of Langebaan, and other local dignitaries, while SAS Flamingo had made a charming effort at decorating the jetty and giving a welcoming party for their arrival. After a few speeches, Cdr Keith Meyer, the OC of SAS Flamingo, asked Mrs Susan van Loggerenberg, the wife of the Officer Commanding the Military Academy, to christen the ship. This she graciously consented to do and the highlight of the week was reached when, in a clear voice, she pronounced, 'I name this ship P1558. May God bless her and all who sail in her' - the traditional prayer. With one clean swing of a heavy chipping hammer, she thereupon broke a bottle of champagne over the ship's bows. In actual fact the ship also received the unofficial name of Susan in keeping with the tradition at SAS Flamingo to name all their launches rather than just using the prosaic numbers allocated to them by the Navy.

Champagne and glass flew in every direction but, miraculously, no one was hurt except the sponsor and the ship's captain. Mrs van Loggerenberg got a piece of glass up her sleeve that cut her arm and a small piece of glass arched over the jetty and sliced Cdr Little's finger. A strange omen indeed, but of what? As the sun set, the party broke up and, after a few guided tours of the Academy's latest acquisition, the guests and crew drifted away and left the ship lying deserted alongside.

Stability problems

From the outset, P1558 was not popular at SAS Flamingo, where she had to be berthed as the Academy facilities across at Saldanha were not suitable. She was a 'bitch' to handle in the tides of the Langebaan Lagoon. Her 'dead slow ahead' was nine knots and if one went from ahead to astern without a 'stop', the engines would cut out. This meant drifting in with the engines stopped and then going full astern to put the brakes on. This was all very well on the quiet waters of a lake, but not on a five-knot ebb tide in Langebaan Lagoon, with a strong south-easter blowing!

P1558 was also a dangerous sea boat. Having been shortened down introduced a design flaw that made her roll dangerously, unless fuel and water tanks were full. This was exacerbated by her armament, which luckily had been removed before her delivery to the Academy. To put it bluntly, she was dangerously unstable in a light condition in any weather state more than a force 4 wind. It was not surprising that SAS Flamingo's personnel wanted little to do with her and disliked going to sea in her.

Realising this, Cdr Little planned his training voyages in short hops of four hours, during which the weather could be relied upon to remain stable, and making sure that the ship was fully ballasted, relying on her speed to get her out of trouble, if need be.

For less than a year, P1558 served as a training ship in Saldanha Bay.

SAS Flamingo, where she was berthed, considered her to be dangerous and unstable.

Early in 1977, Cdr Little was transferred from the Military Academy and his successor, Lt Dave Reid, found P58 a problem. In conjunction with SAS Flamingo, he considered her dangerous and shortly thereafter she was 'traded in' for a more suitable ship, the Shirley Tomlinson, a catamaran-type patrol vessel.

P58 was sent back to Simon's Town where, notwithstanding her stability problems, she was rearmed with a 40/60 Bofors gun forrard, twin 20mm aft and two single 12,7 Brownings on the superstructure abaft the bridge. Thus armed, she was sent up to Walvis Bay, where it was found that she was useless in any area outside the Bay itself, because of her by then very top-heavy configuration. Returned once more to Simon's Town, she was then, rather unbelievably, employed as the range clearance vessel for the Gunnery School, a poor choice if ever there was one. Anybody who has ever been out on False Bay in a south-easter will tell you that this is not the place to be in a small ship suffering from stability problems.

Despite the instability inherent in her design, P1558 was armed and sent to Walvis Bay

for service, where she was found to be completely unsuitable for any duties outside the Bay itself.

Laid up in the early 1980s, no further use could be found for her and she was placed in reserve. In 1986 she came up for disposal as part of the rationalisation of the SA Navy but no buyers came forward. Accordingly, she was stripped down and towed to Walvis Bay for use as a gunnery target during Exercise Magersfontein, eventually being sunk by naval strike craft 90 miles (145km) west of Walvis Bay on 15 September 1988.

In the meantime, in 1976, Malawi had obtained a temporary replacement for its ship, a 9m Fairy Marine Spear Class patrol boat from the UK. There were no delivery problems and the crew training at Langebaan was not wasted after all. In 1983 Malawi further expanded its navy by purchasing a replacement for P58, to the same specifications. Built by SFCN ofVilieneuve-la-Garenne in France, it was constructed in sections, delivered during October 1984 and assembled on the shores of Lake Malawi. She entered service on 17 December 1984 as the Malawian ship Chikalala and, to the best of the writer's knowledge, is still based at the naval base at Monkey Bay.

Well - there it is. The short, rather touching career of a ship that could have been a tremendous naval asset to Malawi but which, apart from serving for less than a year as a training ship, proved to be a complete and absolute dud, causing the writer to wonder who accounted for the 'fruitless expenditure' involved?

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org