The South African

The South African

In April 2002, Stanley Smollan, formerly Private S Smollan, 2 TS, Number 27498, of the Transvaal Scottish Regiment, finally parted with his unique collection of documents and photographs from the Second World War. Smollan handed over the collection to the Transvaal Scottish Regimental Association for preservation in its newly established museum. Smollan, then 82, was amongst the last surviving members of a daring band of Springboks who, in the period August 1943 to January 1944, managed to escape from an Italian Prisoner of War camp, evade recapture and finally slip through enemy lines to rejoin their comrades.

Private Stanley Smollan 2 TS 27498

Smollan's extended adventure began in October 1940 when, at twenty years of age, he joined the 2nd Transvaal Scottish Regiment. After training at Zonderwater, Barberton and Pietermaritzburg, his Brigade, comprising the Transvaal Scottish and South African Police Battalions, was shipped to Egypt, arriving at Suez in May 1941. They were immediately dispatched to El Alamein (at the time, still an obscure desert village) to help prepare the defences. The Regiment then proceeded into the desert, where it was engaged in two actions, at Fort Capuzzo and Sollum.

Solum and Tobruk, Egypt

The attack on Sollum, a small coastal village in Egypt close to the Libyan border, took place in January 1942. It was part of a broader strategy of denying the Axis forces access to the sea and it was here that the Transvaal Scottish battalion went into serious battle for the first time. At 06.40, under cover of an artillery barrage, the Scottish platoons moved down the wadis onto the narrow plain. Close to the enemy positions, they launched a full-frontal regimental bayonet run for forty yards to overrun the forward lines.

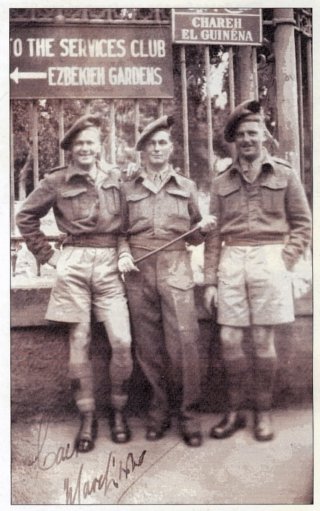

Outside the Jewish Club in Cairo: Herby Justus,

Jim Kinnear and Stanley Smollan (Photo: S Smollan).

On reaching the target, Smollan came up against an unarmed Italian soldier, begging for his life on his hands and knees. He chose not to shoot. At that moment, he turned his head and heard what sounded like 'a huge clap of thunder' as a sniper's bullet scythed across his cheek, ear and neck. The oft-quoted sensation of one's life passing before one's eyes in a time of great peril was literally true in his case. He remembered his own life doing just that, 'like a film'. Dazed and bleeding, but fortunately not seriously hurt, he was removed to hospital. He was one of over a hundred Transvaal Scottish casualties incurred during the successful operation. One of his close friends, John Mendelsohn, was killed in action while another, Phillip Medalie, was seriously wounded and would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

Smollan spent the next few months recovering in Alexandria and Cairo (5th General Hospital, Rosetta). There he was visited by his cousin, Fred Smollan, a former Rugby Springbok and Lieutenant in the Rand Light Infantry. On 20 June 1942, he rejoined his regiment in Tobruk. The timing could not have been worse. The following day, the entire garrison, 35 000 strong, was forced to surrender. Recalls Smollan:

'Our particular platoon was right on the western perimeter and we saw the frightful saturated Stuka bombings of all the outer defences. There was very little left inside. In my opinion it was a hopeless situation. General Kloppers was severely criticized [for surrendering] but really there was nothing there - it would have been a massacre.'

Being on the outer edge of the British position, some of the Transvaal Scottish broke up into small parties and tried to make their way deeper into the desert to evade their captors. A few succeeded, amongst them Company Commander, Captain Paddy Cook. Smollan and three others managed to remain at large for two days before being rounded up by a German patrol. He recalls how the German officer in charge, on learning that they were South Africans, jocularly said to them, 'Why don't you do what the Irish do - join us and tell Britain where they get off'. Of course, they could only reply that they would find this rather difficult to do. 'Look chaps, I'm sorry but I'm going to have to hand you over to the Italians' the officer continued, which he did. Smollan commented on the real mutual respect for one another that existed between Rommel's men and the British and American troops who opposed them.

South African Prisoners of War

The Tobruk prisoners, amongst whom were some 10 000 South Africans, had a grim time of it during the next few months, not because their Italian captors mistreated them but because the latter were not even able to supply themselves properly, let alone tens of thousands of the enemy. They were held in a hastily constructed camp in Benghazi, where a state of near anarchy prevailed until Transvaal Scottish SergeantMajor Cockcroft and one or two others were able to restore a degree of order.

After a time, Smollan and about 2 000 others were transported by truck to Tripoli, a journey that took ten days. There, they were confined in an old Italian barracks in Tarhuna. Conditions there proved to be no better than they had been at Benghazi. There were, for a start, four to five thousand paws in premises that had been built to accommodate five hundred at most. The old cloakrooms and drainage system were not functioning, so that very quickly there was a danger of disease breaking out. There was very little food available for either prisoners or those who guarded them. No Red Cross support could reach them. The situation continued for a number of months, from June to November 1942. Said Smollan of this time, 'We were caught in an ugly position. But we survived it and most of the prisoners, particularly the South Africans, conducted themselves very well. They kept themselves clean, kept their spirits up, exercised where they could. It was a matter of keeping up one's self respect and lasting it out. He added that it became a strict rule that whenever it was possible to shave or polish their boots, they should do so.

The prisoners formed work parties of volunteers who had some knowledge of plumbing and drainage, and these were able to get things in reasonable working order. When the sewage and latrine system was reconstructed, large trenches were dug away from the actual camp. Poles were then placed over these, on which the users would sit and 'do what they had to do' into the trench itself. They were long lines, about fifty metres or so. The rumours would start on one side and carry down to the other, a novel way of disseminating news that the prisoners referred to as 'latrinograms'.

To Italy as a captive

In November, the situation changed dramatically with the German defeat at El Alamein. The prisoners' barracks at Tarhuna were now urgently required, so the inmates had to be hurriedly moved elsewhere. Smollan was amongst those who were loaded onto the ship Coldelana and transported across the Mediterranean to Naples:

'Some 2 000 of us were loaded onto this ship in layers. It was a 10 000 tonner and the first prisoners were put down into the bottom of the hold. The planks were laid for the next layer of prisoners and so on until all were loaded. It was an unpleasant situation and to top it everyone had dysentery, so if you were on a lower level you weren't too well off. Somehow, we survived the trip to Naples, which took four days, ducking and diving aircraft, submarines etc.'

The prisoners were next entrained to Camp 66 in Capua, a small town close to Naples. Most were very sick when they arrived, but here things at last started to improve, especially when the Red Cross parcels containing items such as cigarettes, jam, tea and salmon finally began to arrive. Also highly welcome were the books that trickled in. ('The literary critics judged a book by its length, not by its quality!'). Red Cross materials provided a kind of currency through which the prisoners and their equally needy Italian guards did a brisk trade:

'One would see an Italian soldier with his rifle on the ground, receiving a packet of tea thrown over the strands of barbed wire and in exchange throwing over four loaves of bread, which was the rate of exchange. Ten cigarettes were also worth a loaf of bread and a bar of soap also had its value. But the chaps quickly saw the opportunity to do some unfair trade with the Italians, who didn't know that the tea had already been brewed once or twice, dried on the roof and then repacked. These packets were probably destined for the 'black market' in Rome.'

After about three months, the prisoners were moved to Fara Sabina (Camp 54), about 100 km north of Rome. Between two and three thousand men were held there. Here, life continued pretty much as before, a constant private war against boredom and stagnation, not to mention the lice that had been the prisoners' constant companions ever since the Benghazi days. Smollan was one of several Jewish prisoners in the camp, but at no time was he ever mistreated because of this. In general, he maintains that the Italians did their best for the prisoners in their care.

'We steadily regained our health and found it important that the Red Cross parcel as was the practice be shared amongst two prisoners. My particular friend was Harry Kahn, a prominent sportsman and baseballer and on his return married Hadassah. Both [were] members [of] Houghton Golf Club.'

A memorable moment for the inmates occurred in early August 1943:

'We were lying around the camp one morning, delousing ourselves or attempting to do so, when we heard a tremendous crescendo of noise. Looking up in the sky, we saw a raid on Rome on (this was later confirmed) the railway yards by 350 American four-engined bombers escorted by fighters. You can't imagine the noise that this created. We heard the Ack-Ack and then saw and heard the bombing. There was a column of smoke rising up. The effect on the prisoners was electric. Here we saw our own aircraft. We saw them clearly weaving and signalling - they knew we were there. This was a show of force. Mussolini had been forced to step down and this was to show who was boss. The next thing was Badoglio sued for peace and we woke up two mornings later to find no guards in sight and the prison gates wide open.'

Fugitives

The Hollywood versions of POW escapes are usually accompanied by Eric Williams-style tunneling to freedom heroics, but Smollan's own escape was more Opera Buffa than anything else. About 2 000 prisoners took advantage of their abandonment to break out, but only a handful managed to evade recapture, one of them being Smollan himself. He and five others made for the nearest mountain village, where they were taken under the wing of an elderly couple, Berchina and Attilio Venetonni. The latter, at considerable risk to themselves, took care of the fugitives for the next three and a half months, hiding them in caves in the valley. During this period, the men were in contact with the Italian underground and British agents, who, amongst other things, supplied them with civilian clothes. They were also joined by several other escapees, amongst them Smollan's former Parktown Boys' schoolmate, Royce Schulman (who had served as a Lance-Bombardier with the Natal Field Artillery).

The six original escapees. From left, Colin Stewart, Ron Tacon,

Bill Trout, Cedric Whitelaw, Basil Hall and Stanley Smollan (Photo: S Smollan).

'One would see an Italian soldier with his rifle on the ground, receiving a packet of tea thrown over the strands of barbed wire and in exchange throwing over four loaves of bread, which was the rate of exchange. Ten cigarettes were also worth a loaf of bread and a bar of soap also had its value. But the chaps quickly saw the opportunity to do some unfair trade with the Italians, who didn't know that the tea had already been brewed once or twice, dried on the roof and then repacked. These packets were probably destined for the 'black market' in Rome.'

After about three months, the prisoners were moved to Fara Sabina (Camp 54), about 100 km north of Rome. Between two and three thousand men were held there. Here, life continued pretty much as before, a constant private war against boredom and stagnation, not to mention the lice that had been the prisoners' constant companions ever since the Benghazi days. Smollan was one of several Jewish prisoners in the camp, but at no time was he ever mistreated because of this. In general, he maintains that the Italians did their best for the prisoners in their care.

'We steadily regained our health and found it important that the Red Cross parcel as was the practice be shared amongst two prisoners. My particular friend was Harry Kahn, a prominent sportsman and baseballer and on his return married Hadassah. Both [were] members [of] Houghton Golf Club.'

A memorable moment for the inmates occurred in early August 1943:

'We were lying around the camp one morning, delousing ourselves or attempting to do so, when we heard a tremendous crescendo of noise. Looking up in the sky, we saw a raid on Rome on (this was later confirmed) the railway yards by 350 American four-engined bombers escorted by fighters. You can't imagine the noise that this created. We heard the Ack-Ack and then saw and heard the bombing. There was a column of smoke rising up. The effect on the prisoners was electric. Here we saw our own aircraft. We saw them clearly weaving and signalling - they knew we were there. This was a show of force. Mussolini had been forced to step down and this was to show who was boss. The next thing was Badoglio sued for peace and we woke up two mornings later to find no guards in sight and the prison gates wide open.'

Fugitives

The Hollywood versions of POW escapes are usually accompanied by Eric Williams-style tunneling to freedom heroics, but Smollan's own escape was more Opera Buffa than anything else. About 2 000 prisoners took advantage of their abandonment to break out, but only a handful managed to evade recapture, one of them being Smollan himself. He and five others made for the nearest mountain village, where they were taken under the wing of an elderly couple, Berchina and Attilio Venetonni. The latter, at considerable risk to themselves, took care of the fugitives for the next three and a half months, hiding them in caves in the valley. During this period, the men were in contact with the Italian underground and British agents, who, amongst other things, supplied them with civilian clothes. They were also joined by several other escapees, amongst them Smollan's former Parktown Boys' schoolmate, Royce Schulman (who had served as a Lance-Bombardier with the Natal Field Artillery).

Years later, Smollan described what this period was like:

'Life in the valley was like being in a Garden of Eden, with fruit and vegetables of all descriptions and hot food brought to us by the Venetonnis. At night we went up into the villages to listen furtively to the BBC, which with its signature, the opening bars of the Beethoven Fifth, was a ray of hope to all friends of the Allies affected by the war. The Italians were urged to support the prisoners and told that they would be rewarded, and thus we survived for that period.'

Semi-idyllic as this existence might have been, particularly after a year behind barbed wire, German activity in the area was increasing and, at the beginning of 1944, Smollan, Schulman and two others, Colin Stewart and William Berridge, decided to make a break for the Allied lines. Apart from the fear of recapture if they stayed where they were, there was also the safety of the kindly Venetonnis to consider. Before dawn on 10 January (which happened to be Smollan's 24th birthday), they set out from Montorio Ramano, proceeding through the snow and arriving in due course at the village of Gerano in Tivoli. There, they were sheltered for a number of days by the De Lellis family before again being contacted by the underground and informed that an Allied landing had taken place at Anzio, about 130 km away.

The Allied lines ' ... We set out after being told to stay in the fields alongside the roads and to follow the Germans, because that's where they were going. By a miracle, on day four, after walking the 130 kilometres, we got into a canal in the middle of the two Allied landings. There was shelling overhead and the Royal Navy firing in from the sea. We suddenly saw the sea and came up through the canal and here we were challenged. We thought, "Oh hell, this is IT! We've come so far only to be caught!" But it was the Americans, who took us to their HQ, where we were put under arrest (we had no papers, of course) and handed over to the British. We were in a state of complete exhaustion, and really didn't know what was going on.'

Stewart's description of the above better captured the drama and euphoria of the moment: 'On the other side of the canal we crawled through the barbed wire and dropped suddenly as we heard a strange voice shout "Halt!" We could not tell whether the sentry was a German or not, so we lay still on the ground and heard the safety catch of a rifle click back. We were soon discovered. Then a friendly voice above us shouted: "What the blazes are you doing there?" We nearly mobbed the sentry in our excitement.'

It would take some time before the four's credentials could be established and they could begin their return journey (and, even then, it would take many thousands of kilometres of travelling on a number of different ships before they saw South Africa again). During this period, they were interviewed by the well-known British War Correspondent, Vaughan Thomas. Before returning home, Smollan and Schulman spent some time in a UN camp that had been set up for refugees, many of them Jews or Gypsies, who had fled into liberated Italy from all parts of Europe. Providentially, there was a South African Jewish army chaplain in the camp, Moshe Nates, who helped them back to South African Headquarters. There they were identified, deloused and given medical treatment and warm army clothing.

On 18 February 1944, Mrs C Smollan received an official telegram reading simply: 'Department of Defence has pleasure in informing you that your son 27498 Pte Stanley Solomon Smollan arrived Egypt 13 Feb'. It was the first news she had of Stanley since June 1942, twenty months previously. He had been listed as 'missing'. That same month, the Rand Daily Mail (for whom Berridge would later work as a reporter) published a full report on the affair, entitled 'Stirring Story of Springboks' Escape'. It was noted that the four were the first escaped South Africans to rejoin the Allied forces then engaging the Germans in that area.

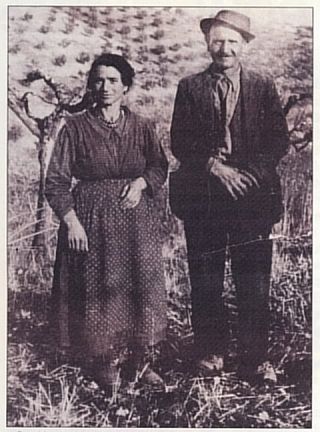

Berchina and Attilio Venetonni, who, at great risk to themselves,

took care of the South African fugitives for three and a half months.

(Photo: S Smollan).

Homecoming

Smollan and his companions were then sent by rail to the Italian naval base in Taranto in the south of Italy and then by troopship to Alexandria in Egypt. Seven days later, they were flown to Waterkloof Air Base in Pretoria by the South African Air force, arriving to a warm official welcome to which their families had been invited. They were given three months' leave. At the end of it, they received instructions to proceed to Military College to be interviewed by Brigadier Klopper. Thereafter, they underwent a Rehabilitation PT Course, at the Physical Training Battalion headed by none other than the legendary rugby Springbok, Lt-Col Danie Craven. Concluded Smollan, 'Soon after, it was decided that we had all done our bit, and so were to be de mobbed and returned to civvy life again. We were paid out our accumulated army and civilian employment pay (my employers having put me on half pay for the duration of my time in the army), plus £37-10 to buy a new outfit of clothes, and that, for us, was that.'

Civilian life

After the war, Smollan joined his father's insurance business. He married Ruth Perlman in 1947 and the couple had one son, Jeffrey. After Ruth's passing in 1994, he married Minna Kay. Now 89 years old and still in excellent health, Stanley continues to maintain a close association with the Transvaal Scottish. In March 2009, he was invited to lay the wreath on the Memorial Day for the First, Second and Third Transvaal Scottish Regiments in memory of the Regiment's activities in Abyssinia, Sidi Rezegh and Sollum. On a lighter note, he participates in the annual regimental bowls tournament between the Scottish, the Sappers and the Gunners, and is the only Second World War veteran still playing. (The Jock Column, September 2008: 'There was a poignant moment during the celebrations when Stan Smollan (2TS) received a standing ovation when Paddy Clarence presented him with a set of regimental cufflinks and tie pin for valiant effort. Stan at the tender age of 89 and the only TS WW2 veteran playing in the competition, committed himself to playing all eight gruelling games without a whimper making sure of the venue getting himself there and sticking it out.')

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org