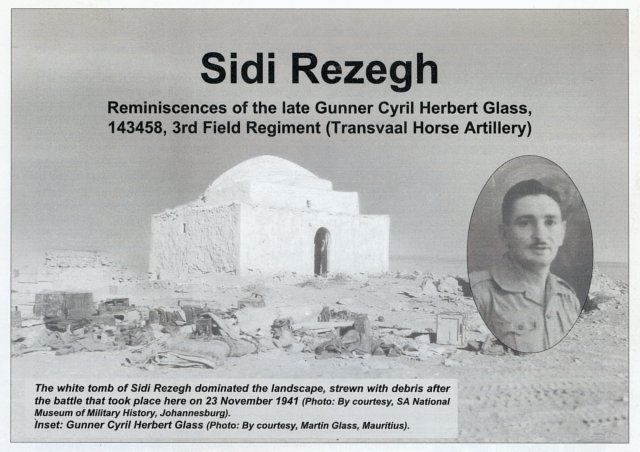

The South African

The South African

Mersa Matruh, Egypt

We had just moved up to Mersa Matruh, after having been at Amariya, where we had been re-formed into artillery regiments from the old-style brigades that we consisted of in Abyssinia, and where we received our introduction to the 25-pounders. Life was pleasant at Mersa Matruh, where we occupied gun-pits and carried out the later part of our training in desert warfare, with special attention to desert formations and tank-shoots. We were able to swim every day and to get a regular supply of beer, over which we gathered for an evening chat or a sing-song. Life was fairly normal, apart from an occasional night-raid by Gerry [German] planes.

Photo: By courtesy SANMMH

It was at Mersa Matruh that that we really came into contact with the Australian, New Zealander and British troops, and I recall an evening when we were drinking with some Australians and, in the course of conversation, one of them passed the remark: ' ... and we went on manoeuvres, and the next thing we knew we were tearing into the Ities [Italians].'

So, when, a few weeks later, we set out on extensive manoeuvres, we all had a fair inkling where it would lead us. We met up with the rest of the 5th South African Brigade well south of Mersa Matruh, and, for about ten days, we went through various manoeuvres, gradually working our way westwards. When, one day, we were warned to watch out for enemy aircraft and ground patrols, we knew we were well on our way.

We passed through Mussolini's boundary wire [into Libya] on 18 November [1941] and camped that night well into enemy territory, but so far had seen nothing of him, either on land or in the air. But, all through the night, we could see the flashes of guns away to the north and we knew, definitely, that the attack had started.

25-pounder field guns issued to South Africans in North Africa

and used to devastating effect against German armour at Sidi Rezegh

(Photo: SANMMH).

We continued to move towards the west the following day and the next day saw us swinging to the north. We experienced our first attack from Stukas and later were strafed by fighters. Our planes were very much in evidence and during the day we saw the spectacle of planes crashing to earth or bursting into an orange ball of fire in the air. It was difficult for us to distinguish the planes at that time and we hoped that each one that crashed was a Gerry.

On Friday morning, after we had been travelling in desert formation for several hours, we received a 'tank alert' and our guns moved up for their first action. We moved to the head of the convoy and dropped into action and got the guns on line. We engaged the enemy tanks at long range and they withdrew under our fire and our tanks took up the attack. For the rest of the afternoon, we were spectators of a tank battle, which continued into the night. We withdrew at dusk to a position 1 000 yards (914 m) to our rear and bedded down for the night. Our 9th Battery had had a more grim experience with tanks and had engaged them with open sights, accounting for a number of tanks, and they had had six men killed and two wounded.

Sidi Rezegh

The following morning, on 22 November, we received orders to move forward several miles and engage the enemy at 1 200 yards (1 096 m). They were holding an escarpment and, at such short range, we expected to run into some lively fireworks: While we were getting into action, we saw the first enemy prisoners coming in, captured on an aerodrome on our right flank, and Gerry's shells were bursting quite close to them as they were being marched away.

Soon after lunch, our infantry, the 3rd Transvaal Scottish, moved forward and we put up a barrage for them and very soon Gerry was replying. Our infantry were held up on a ridge about 1 000 yards (914 m) in front of our guns and could make no headway.

Meanwhile, machine guns, mortars and artillery on both sides were going for all they were worth. Gerry planes were over, strafing, too, and towards sunset it was obvious that our infantry could move neither forward, nor back. During the night, the infantry withdrew slightly and dug positions about 400 yards (365 m) in front of our guns, and our O Pip (Observation Post) did likewise. We dug the guns in, to some extent, and settled down for the night.

Our casualties that day had been one officer and three men wounded and two men killed. The infantry, we heard, had had heavy casualties and their OC (Officer Commanding), Col Kirby, and their 2IC (second-in-command), Major Gartly, had both been killed.

The morning of 23 November was comparatively quiet. Gerry planes were overhead, strafing, and some of our tanks went in, but came out in a hurry. At about 12.30, Gerry started his counter attack, opening up with everything he had, and we replied. His shelling was terrific, but the most demoralising fire was from his mortars, which had a crack like a whip and the shrapnel kept low and we were well within range of them. One mortar shell killed two of our gun-team and another threw the empty ammunition boxes several feet in the air. The other guns had casualties, too. Infantry being brought up in support, the South African Irish, were hit before they could pass our guns and were being kept down. We kept the guns firing as the day wore on towards sunset, which was what we were praying for by now.

Tanks had broken through our wagon lines during the early afternoon and had taken some prisoners, including our Brigadier. The ammunition trucks had been captured and numbers of our vehicles had been hit and were burning. Our O Pip had reported tanks massing on the El Adem aerodrome on our right flank, but was told that they were New Zealanders. This report later proved to be wrong; they were Gerry.

A daring escape

Our echelon had been cut off and we were short of ammunition. We had used all available ammunition, but the men were still on the guns, except those who had been wounded or killed. We had a number of casualties and our GPO [Gun Position Officer] had been killed.

Some of our men were doing splendid work, getting the wounded away, and our maintenance signaller had done a wonderful job on the telephone line to the O Pip, under continuous fire. The line was being hit incessantly, but he repaired it each time, until he was hit in the afternoon, when our communications went down completely.

I was sent up to the O Pip with a message to tell the O Pip officer to hold on to morning. I made my way there on my hands and knees along the telephone cable and contacted the O Pip officer. I took cover from small arms fire in a vacant slit trench. The Gerry artillery and mortars had ceased firing and I started on my way back to the guns at the same time.

The infantry started withdrawing. The reason was apparent for, on my left, the tanks that had massed on the EI Adem aerodrome were German and were moving across between our O Pip and towards the silent guns. I decided to return to the O Pip and took cover in the same slit trench I had just vacated. I was certain that it would be only a matter of time before I was a prisoner of war. However, our O Pip officer, Captain Lombard, had other ideas and coolly ordered us to lie low as the tanks passed us. By now it was dusk and he said he thought we could get away as soon as it was dark. It would be moonlight until about 23.30, but at about 19.30 he thought it would be advisable to move from our position, so we started off southwards on our hands and knees. There was Gerry movement all around us and we had to pass several columns on our way out.

There were eight of us in the party: Captain Lombard, gunners Bradbury, McLeod, Charman and Glendinning, two others and myself. We had not moved very far when we spotted the first Gerry column moving across our path and we lay very still and our hearts missed a beat when it stopped not more than fifty yards (45 m) from us. Someone shot up several Verey lights and shouted some words in German.

I had resigned myself now, for I was sure we had been spotted. But, shortly afterwards, a tank joined the column and it moved away. We moved on, but not very far before we saw another column coming directly towards us, but slightly on our left flank. It was agony watching it approach. The fact that we could see two motorcyclists riding on our side of the convoy did not improve the situation. However, the column passed and the motorcyclists actually zigzagged amongst us to miss our bodies. That column stopped only 25 yards (23 m) past us and several Germans alighted from the vehicles and started to chat.

Then, one of our party's nerves caught up with him and he shouted across to the group that he wished to surrender. We were all horrified, but, fortunately, they took no notice of his plea; most likely, they thought he was wounded, for there was somebody lying near us, groaning. Shortly afterwards, the column moved off and, with a heartfelt sigh of relief, we were on our way again, only to be rudely shaken by a stick of bombs dropped not more than 100 yards (91 m) away by what we imagined to be one of our planes.

Meanwhile, white Verey lights were going up all around and there were scores of burning vehicles on our left. We were still moving forward on our hands and knees, gradually drawing away from the light cast by the flares and the fires. We were feeling much safer and a little pleased with ourselves when, suddenly, we saw a solitary figure in front of us, moving across our path. We fell to earth and held our breath, for he had stopped and was turning towards us, but soon went on his way.

With his back towards us, we moved on and soon felt that we could walk upright quite safely. Imagine our surprise when someone looked back and saw the solitary person following us, and with his warning we were once again hugging the earth.

We saw the person stop and stare, then crouch down and peer, and every now and then a flare would go up and light up the place and we expected him to call for assistance. But, instead, he came towards us. Our officer was ready with his revolver and leaped forward as the person drew near. I could just hear the words: 'Does the Baas want a drink of water?'

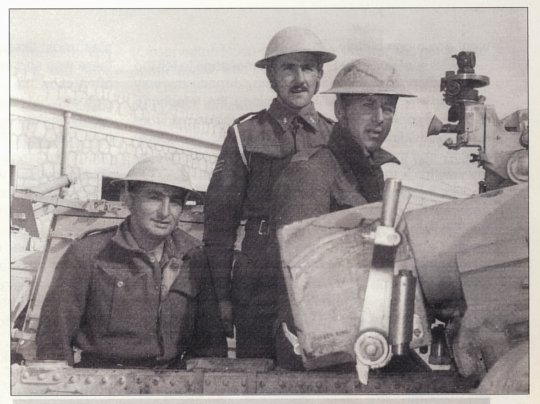

Lt Col Ian Buchan 'Tiger' Whyte, DC, and a captain of the 3rd Field Regiment (THA)

pose in front of some of the 32 German tanks knocked out by their guns at Sidi Rezegh

on 'Totensonntag', 23 November 1941

(Photo: By courtesy, SA National Museum of Military History).

What a scare the Cape Corpsman had given us and received himself! What a relief it was to know that we could still continue on our way and his water would, no doubt, be welcome on the morrow.

It was then 22.00, and, in view of the fact that we had been so easily followed, we decided to lie low until the moon sank below the horizon.

As soon as the moon had set, we continued on our way. Our officer had decided that we should travel south-east, following, as near as possible, the path the Brigade had moved along towards Sidi Rezegh. We walked until about 04.00 the next morning, passing over numerous tank tracks and heading towards the only place that seemed free of Verey lights. We came across a derelict case of Gerry biscuits and later found a petrol tin about a quarter full of rainwater, with which we filled the few water-bottles we had. We felt that we could sustain ourselves for several days, if need be. By 04.00, everyone was dead beat and, after posting a guard, we got down on the wet ground and slept. After half an hour of it, I was too cold to sleep, so I took over the guard, and, as the others were all asleep, I continued until it began to get light.

As the dawn broke, I noticed, in the half-light, a column of vehicles about 500 yards (457 m) away. I immediately wakened everybody and we took cover in some low desert scrub, which, at the most, was only 18 inches (46 cm) high, but, by lying very still, it afforded some cover. The vehicles, with the rising sun behind them, were hard to distinguish, even with the field glasses, and it was an hour before our officer could be sure that they were our troops. One man, Charman, was sent over and it was a relief when he signalled that everything was in order.

Some survivors of Sidi Rezegh, 23 November 1941. After the battle,

Gunner C H Glass (left) and what remained of the 3rd Field Regiment (THA)

returned to Mersa Matruh in Egypt to be re-formed as a fighting unit

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

Rescue

Soon, we were drinking hot coffee, eating sausages and handing around our Gerry biscuits. We had joined up with the South African 1st Brigade Reconnaissance vehicles and, after we had eaten, they took us to 1st Brigade Headquarters for interrogation. Then we were attached to one of the Brigade's artillery vehicles until orders were received as to what was to be done with us.

As we sat eating supper that evening, a message came through that a strong Gerry force was expected to attack and that all vehicles were to be ready to move at a moment's notice. However, the night was quiet.

The following morning, however, Gerry attacked with tanks and artillery and, later, there was an infantry attack, but it was repulsed. We had dug shell slits for ourselves in the morning and they proved very useful in direct line of an artillery duel between our medium guns and Gerry's. Fortunately, nobody was hit, but it wasn't at all comfortable.

That night, as the enemy was seen to be massing tanks, the Brigade withdrew. Everything moved out very orderly in formation and I could not help but contrast it with what had been our plight a couple of days previously. The following morning, we were bundled into a captured Itie vehicle and sent along to battle headquarters, where we were joined up with what was left of the 5th Brigade, and that was not much, though most of the men were prisoners of war.

The men from our regiment and the few vehicles and guns that had come out were gathered together and we set out on the trek back to Mersa Matruh to go through the process, once again, of being re-formed.

A few nights later, at Mersa Matruh, we gathered together to drink to the health of Captain Lombard and to give him our thanks, for it was entirely due to his coolness and resourcefulness that we were able to escape.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org