The South African

The South African

Introduction

Colonel William Henry Sykes has previously featured in the Military History Journal (Talbot, P A, 'Costing the British and French armies of 1864' in MHJ, Vol 13 No 4, December 2005, pp 148-53) and this paper has arisen from further research on Sykes's statistical scrutiny of military matters. The paper is concerned with Sykes's earlier statistical accounting analysis performed on the armies of the East India Company prior to the Great Indian Mutiny of 1857-8 (The author acknowledges the assistance of the University of Aberdeen Library and Historic Collections in providing a copy of Sykes's original paper). This work provides not only a valuable insight into the health of the East India Company Army troops which is distinguished between the different presidencies of the Company, but also by the further analysis and comparison between the Company's European and Native Troops that challenged widely held preconceptions. Sykes's examination is both representative of the 'Early Victorian Statistical Movement' and knowledgeable because of his intimate connections with the East India Company. The paper also serves to provide further insights into Sykes's military career in early nineteenth century India.

The East India Company

To understand the context of Sykes's work, it is necessary to understand the origins and the nature of the Company with which he was to be connected for over half a century as a company army officer, statistician of the Bengal Presidency, and its last chairman. The East India Company, or 'John Company' as it was widely known, was a peculiarly unique organisation within the British Empire. It was founded by royal charter granted in 1600 and was originally named 'The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading in the East Indies'. After merging in 1709 with another company trading in the East, it became 'The United Company of Merchants of England trading in the East Indies'. This remained its legal title until 1874 (when its affairs were eventually wound up), but from the passage of the Charter Act of 1833 it became habitually referred to as the East India Company in most parliamentary documents and debates. Occasionally it was referred to as the 'Honourable Company' but it was more often called 'John Company'. The origins of this latter name are obscure, and may be a reference to 'jehan' (meaning 'powerful' in the native Indian tongue [Wild, 1999, p 7]). The Company was immensely powerful as the British government successfully sub-contracted its Indian imperialism to commercial strategies.

The early British trading activities in the East had brought it into conflict with the other competing European powers, notably the Portuguese, Dutch and French, as well as the local native powers, which necessitated the Company raising its own military forces to protect its investments. These commercial rivalries often spilled over into local native wars or became part of distant European conflicts. The Company's centre of power became established in India and its first permanent base was founded in Madras in 1639. This was followed by other garrisoned trading bases in Bengal as its sphere of influence expanded. This brought the Company into direct confrontation with mainly the French East India Company (Compagnie des Indies) during the First Carnatic War (1744-8) and the Second Carnatic War (1749-54) as both sides allied themselves with the warring local Indian princes.

During the remainder of the eighteenth century, the British inflicted crushing defeats over the Dutch on sea and land, in 1759 at the Hooghly River and at the main Dutch port at Chinsura, while Portuguese possessions were henceforth confined to Goa, Diu and Daman (Dupuy & Dupoy, 1993, pp 764-5), which effectively eliminated both of these powers' influence in India. This left Britain and France to dispute dominance in India, and a succession of British victories at Plassey in 1757, Masulipatam in 1759, and Wandiash in 1760 finally established British supremacy, which resulted in the dissolution of the Compagnie des Indies in 1769.

This did not end the Company's warring activities as it continued to expand its sphere of commercial operations, bringing it into conflict with local native Indian powers, which led to the First Maratha War (1779), the Second, Third and Fourth Mysore Wars (1780-1800), the Second Maratha War (1803-4), the Hindustan Campaign (1803), Holkar's Offensive (1804) and the Third Maratha War (1817-18). Although France was peripheral to these conflicts, it intrigued with the native Indian rulers to foment trouble in order to divert British military resources away from the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars being fought in Europe. It was amongst these early nineteenth century Indian conflicts that Sykes served.

The East India Company Armies

Sykes entered service with the Bombay Army in 1804 as a junior officer when he was fourteen years old. He served under Lord Lake at the first siege of Bhurtpoor (1805) during Holkar's Offensive where four British assaults were repulsed with heavy losses. Sykes later commanded a native regiment at the battles of Kirkee and Poona in 1817-18 during the Second Maratha War ('Obituary: The late Colonel Sykes' in Illustrated London News, Vol 61, 1872). The Marathas or Pindaris were an eclectic mix of castes and tribes ravaging central and southern India, which included an attack on the British garrison at Kirkee, a suburb of Poona where the badly outnumbered British garrison repulsed the enemy. Although Sykes's obituary is less precise about his involvement in subsequent battles, it alludes to his participation in other imprecise military operations, which may have possibly included the ultimate defeat of the Mahrattas.

By then, the East India Company had effectively, through fortuitous circumstances and with the tacit approval of the British government, become a corporate state whose role extended far beyond the original commercial objectives of the organisation. Indeed the Company had created its own civil service which played a paramount role in fashioning British India (O'Malley, 1931, P xi). One of its pre-eminent civil servants was John Mill, the author of Elements of Political Economy (1821), who explained, 'the business, though laborious enough, is to me highly interesting. It is the very essence of the internal government of sixty million people with which I deal' (Micklethwait & Wooldridge, 2003, p 44).

The Company had also been granted, by the British government, the powers to wage war and negotiate peace treaties, albeit with any non-Christian nation (Dupuy & Dupuy, 1993, p 764). This arrangement admirably suited the British government because it relieved it of the large expense of defending India, although it did provide small contingents of Regular British Army troops which permitted it to influence military operations by proxy. Nonetheless, the extraordinary position was that the Company had created a large private army, administered and paid for by the Company, obeying their own Commander-in-Chief, which was entirely separate from the Regular British Army. Thus, as the Company had grown it had become a significant military power in its own right, which included not only its own three separate armies but its own navy as well - by 1857 the Company's fleet consisted of 43 warships and 273 European officers (Wild, 1999, p54).

The Company's armies were a mixture of predominantly locally recruited native regiments and a smaller number of European regiments. Although the majority of native regiments remained loyal, there were localised incidents of mutiny as occurred when the 47th Native Infantry Regiment mutinied at Barrackpore in 1824. This mutiny was eventually put down with some slaughter by the Regular Army, and European and Native Company regiments. It was reported that the'26th and 62nd Regiments of Native Infantry, which were also under marching orders, behaved throughout the morning with the most perfect steadiness' (Gupta, 1959, p 35). The European regiments were initially raised from discharged Crown troops in India but later rank and file recruits were enlisted in England at a depot near Brentwood in Essex for posting to units in India (Brereton, 1986, p 80). The officer corps, unlike the Regular Army, did not indulge in purchasing commissions, but were promoted by merit. The reasons for Sykes being entered for a Company military career remain obscure since there are no ostensible family links for service, and a commission in the Company's service was always held to be socially inferior to a Crown commission, and could often be regarded as disreputable. The Company's European officer corps at this time was notoriously undisciplined, having arrested their Governor-General (who subsequently died in their custody) in 1776 in reprisal for his ordering the arrest of the army Commander-in-Chief who had been accused of inciting his troops to mutiny. A more serious mutiny occurred later in the Madras Army during Sykes's era, in an event dubbed 'The White Mutiny' in 1809, which led to 21 officers being court-martialled, cashiered or dismissed before order was restored. This incident was deliberately obscured by the authorities in order to preserve stability (Cardew, 1929).

The Company forces were organised on a confusing ad-hoc basis between the three Presidencies (administrative areas) of Bombay, Madras and Bengal, with the latter being the most important. At first these forces were predominantly infantry-based with some European artillery relying on the hiring of local irregular cavalry forces when the occasion demanded. Ultimately the Company's directors' opposition to raising an expensive regular cavalry arm on the grounds that it would reduce profits was overcome by the tactical necessity of having its own reliable horsemen. At its zenith the Company Army stood at 250 000 men of whom no more than 45 000 were European officers and other ranks (Wild, 1999, p 133). It was this force that Sykes subjected to his statistical accounting analysis in order to discover how healthy its troops were.

Statistics

Statistics in nineteenth century terms was not the rigorous mathematical discipline that it is today. It was part of a widespread European phenomenon of gathering and recording diverse and eclectic data both for government and personal usage. Sykes had become exposed to this burgeoning movement when, in 1820, he had returned to England on leave. It was normal Company practice to award three years' leave to officers with ten years' service (Gourvish, 1972, pp 48-9). Sykes used the opportunity to tour the continent and study scientific matters and also to learn foreign languages. He returned to India in 1824 with the rank of captain and was appointed as the 'Statistical Reporter' to the Bombay Presidency until June 1833. Sykes retired from the Company's Army in 1837, having attained the rank of colonel, and returned to England, where he became an active member of the Statistical Society, publishing his analysis of the Company's armies sometime around 1845. The Society was an important manifestation of Victorian cultural enterprise between 1832 and 1897 when, in an increasingly uncertain world, statistics could be used to address risk by identifying, with precision, areas of safety and, conversely, areas of danger. Statistical analysis suggested that the diverse risks facing the British Empire could be mitigated or avoided (Freedgood, 2000, p 1) and the most important part of that empire was India, the 'jewel in the crown'. This valuable economic possession perpetually faced the danger of attack by rival European powers. As the nineteenth century progressed, Russia emerged as the new potential enemy and the imperative for a strong, healthy army to deter any hostile predator became a prerequisite.

Bombay Army Analysis

Sykes's detailed health analysis of the Company's armies involved two separate areas. Firstly, he evaluated the 'The Vital Statistics of the Bombay Native Army at every age from 20 to 52 for the years 1842, 1843 and 1844' based on the documents drawn up by the Military AuditorGeneral in Bombay. This exercise was undertaken to determine the effect of the climate on the health of troops stationed in Scinde Province, analysed over six separate and detailed tables. The second evaluation - 'The Vital Statistics of the Indian Army, European and Native, from 1825 to 1844' - was more extensive. The Indian Army was used as the generic term for the three separate armies of the different Presidencies analysed over another six separate tables. The East India Company's Army analysis arose from an Order of the House of Commons issued in June 1845, and it appears Sykes, assisted by a Mr Neison, used this as a framework for a more detailed scrutiny.

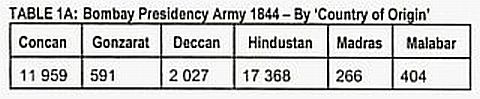

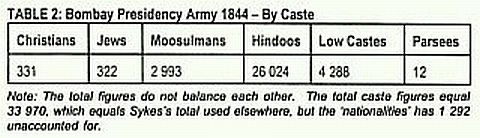

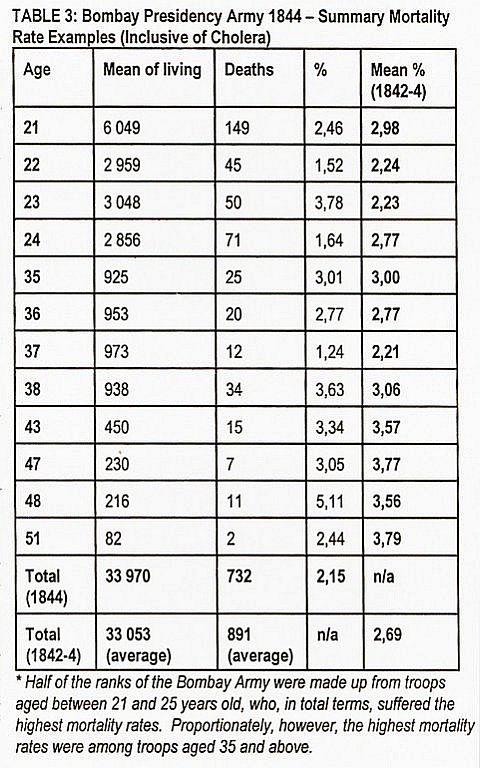

It is impractical to reproduce all of Sykes's reduced tables containing their myriad figures, so a representative selection of summarised statistics is employed below to illustrate the techniques that Sykes used to draw his conclusions. Initially, he provided a native analysis of the Bombay Army between 'country of origin' and castes for the years 1842 to 1844. The year 1844 (Tables 1 a and 2) has been arbitrarily selected as an example. It is apparent that the Bombay Army recruited mainly in the Concan (Mahrattas) and from Hindoos in Hindustan. Sykes mentions that 'the Jews although small in number are valuable, from their steadiness and ability' (Sykes, 1845, p 3). The Bombay native force was then analysed from the ages of 21 to 52,and the numberof deaths recorded against each age group (excluding combat deaths). This data was then placed in separate tables and converted to percentages and mean mortality percentage rates. A composite representative sample of the most significant figures from 1844 (Table 3) is reproduced here.

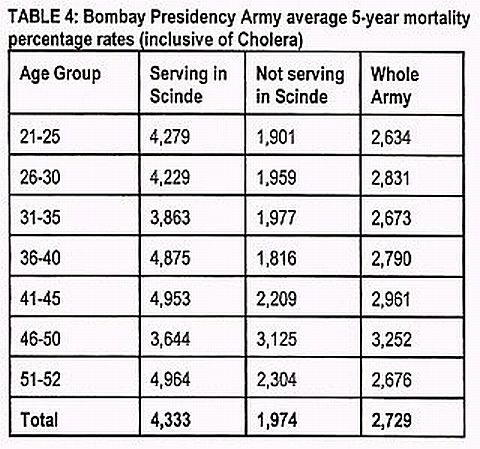

A similar analytical exercise was then undertaken to determine the impact on mortality rates of service in Scinde Province (Table 4). This province, lying in a valley between India and Afghanistan (now in modern Pakistan). had been conquered by the British in 1843 following an attack on the British residency in Hyderabad by Baluch natives. The British general in command, Sir Charles Napier, a Company officer, stated, 'We have no right to seize Scinde, yet we shall do so, and a very advantageous, useful humane piece of rascality it will be' (Duncan & Walton, 1991, P 37). This campaign was a remarkable example of military leadership as Napier's force of 5000 was heavily outnumbered by 60 000 well-armed Baluchis, but he won two major battles nonetheless at Miani and at Hyderabad in 1843. At the conclusion of the campaign, he despatched his famous one Latin word message, 'Peccavi' (translated as 'I have sinned') to the Governor-General of India (Dupuy & Dupuy, 1993, p 862).

Sykes commented that the health of the Bombay Army serving under their own Presidency with a 1,97% mortality rate (excluding Scinde, which was not part of the Bombay Presidency), was almost equal to the health of British troops serving in Malta (1,87%) and better than the British garrison at Gibraltar (2,2%) and the British troops serving in Canada (2,0%) and the Ionian Islands (2,83%). However, he recognised that, over a longer period of time, this advantage disappeared, when cholera and service in Scinde were considered where the mean mortality rate of 2,729% exceeded even the worst British garrison figures produced in the Ionian Islands. He believed this was due to the effects of the adverse climate in Scinde, and to cholera.

The Company Army - The Europeans and the Native Troops

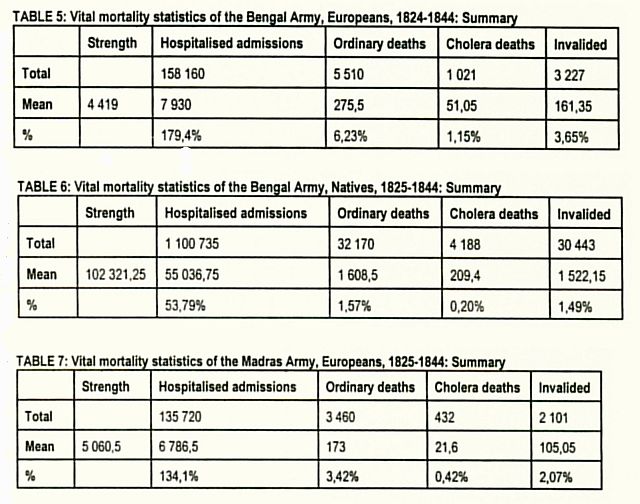

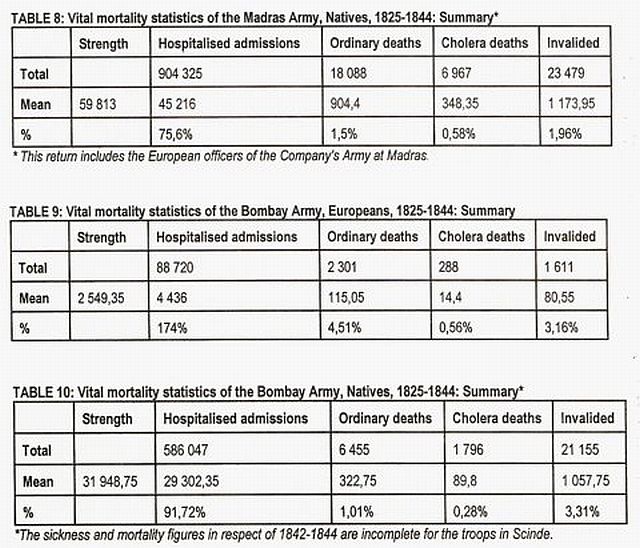

Each of the Presidencies contained a mixture of entirely European regiments and the far more numerous Native regiments with European officers, as was the case in Sykes's own regiment. Sykes constructed separate tables of analysis for European and Native troops for each year from 1825 to 1844 for each Presidency. Again Sykes's detailed tables are presented below as consolidated summaries (Tables 5-10).

The obvious conclusion that Sykes drew from this analysis was that the European troops' health was inferior to the Native troops throughout the Company's armies, although Sykes adds a caveat to the reliability of the hospital admissions figures: 'I must disclaim any confidence in the admissions into hospitals as types of general sickness; for one soldier goes twelve times into hospital during the year, and in the total admissions counts as twelve men, while another soldier remains in the hospital the whole twelve months, and counts only as one admission. No statistical law therefore can be legitimately deduced from the mere totals of admissions into hospital' (Sykes, 'Vital Statistics of the East India Company's Armies in India, European and Native', c1845, p 8).

Nonetheless, Sykes, after repeating his statistical findings in exhaustive narrative detail, returned his focus to determine why the European regiments were more sickly than the Native regiments. He attempted to rationalise the likely causes for the apparent imbalance because, '[a]nother fallacy, which these tables dissipate, is the asserted superiority of the European over the Native soldier in resisting the influence of cholera in the first instance, and in the power of rallying from its effects when attacked. The European, it is said, is a robuster man than a Native: his fibre is more rigid, and his stamina stronger: the Native being comparatively feeble and washy from his habits of life, and from insufficient nourishment of his farinaceous or vegetable food. Now the tables show the very reverse to be the case' (Sykes, 'Vital Statistics of the East India Company's Armies in India, European and Native', c1845, p 19).

Both the European and Native regiments endured the same climate and vicissitudes of military life and, indeed, the European barrack accommodation was often superior. As Sykes indicated, even amongst the less healthy Europeans, a wide range of illness occurred, causing the renewal of the Bengal European regiments every ten years, the Bombay regiments every twelve years, and the Madras regiments every seventeen years. Sykes suggested answers to the problem, but did not have an absolute solution for redressing what he termed the Europeans' 'habits of life', especially with regard to drinking and dietary habits, and the lack of physical and mental stimulation. Insobriety was widely recognised as a particular vice amongst the European ranks as an anonymous soldier wrote in the Calcutta Gazette (20 October 1828): ' ... the daily issue of spirits to the troops - a practice which inundated the Barracks with raw liquor, generally of the most deleterious quality, thereby inducing loss of health and character - and in a great measure, causing all the miseries attendant upon drunkenness' (Gupta, 1959, p 328).

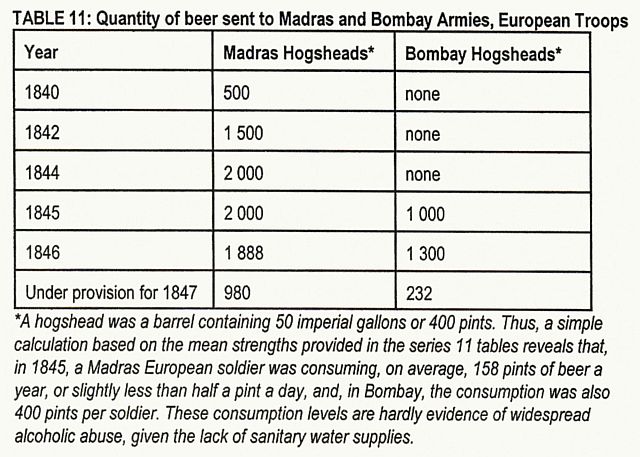

Sykes suspected that alcohol, and the quality of the alcohol, represented a particular problem. This inspired him to assemble a series of supporting statistics for the Madras and Bombay armies (Table 11). No figures are given for the Bengal Army, because they were not supplied with any beer as part of their rations. Instead, the Bengal Army was supplied with spirits. Sykes provides information, without any statistical analysis, of the types of spirits supplied, ie, rum to the Bengal Army, Columbo Arrack to the Madras Army, and Bhandoop Spirit to the Bombay Army. Sykes argued that the combination of beer and arrack, which he described as a wholesome spirit, contributed to their lower mortality rates, and that the later introduction of beer in the Bombay force, combined with a spirit more wholesome than rum but inferior to arrack was responsible for the reduction of mortality rates. He concluded that, 'I cannot help associating the increased consumption of malt liquor by the Madras Europeans with their comparative healthiness and the gradations of the mortality rates in the Bengal and Bombay European troops as partly influenced by the quality (no doubt much more than the quantity) of the spirits they respectively consume' (Sykes, 'Vital Statistics of the East India Company's Armies in India, European and Native', c 1845, p 10).

Conclusion

Sykes's analysis debunked the myth of the more robust European soldier in comparison to his Native counterpart, '[w]hether it originates in physical or moral causes, whether in the atmosphere, or the habits and treatment of the men, should be questions for grave investigation' (Sykes, 'Vital statistics of the East India Company's Armies in India, European and Native', c 1845, p 10). He also exposed the perceived gravity of cholera as another myth: 'Another important result from the compilation of this paper is the necessary removal of all rational grounds for that panic terror, which has hitherto obtained respecting the intensity and extent of that assuredly very shocking malady, Asiatic cholera ... calmly cast our eyes over the mortality rates of the whole Indian Army ... over the last twenty years was ... 87 Europeans and 662 Natives' (Sykes, c 1845, pp 22-3).

In his opinion, the European soldier's health problems in India were mainly to be associated with poor dietary habits and excessive alcohol consumption. In the latter case, however, it was indicated that moderate beer consumption actually improved the troops' health, implicating poor-quality spirits as a more destructive element. Nonetheless, he also noted that some native troops, principally those in the Madras Army and especially the Moosulman in the cavalry and low caste Hindoo's in the infantry, ate and drank very much like the Europeans and suffered similar mortality rates.

Sykes also hinted at psychological reasons for the higher European mortality rates, which he suggested arose from a lack of mental stimulation. Although this was impossible to quantify, Sykes surmised that the European troops' health would improve if '[t]he European soldier is improved in his habits, until he is made to understand that temperance is for the benefit of his body, libraries for the benefit of his mind, exercise for the benefit of his health, and savings banks for the benefit of his purse. The climate of India is less to blame than individuals: for in the case [where] foreigners find the people of a country healthy, they should, to a certain extent, conform to the habits of the natives to be healthy also' (Sykes, c1845, p 25).

It is uncertain whether Sykes's analysis proved influential in guiding the Company's army health policies. The existence of the three armies ended in the wake of the Indian Mutiny (1857). The ultimate demise of the Company's armies reflected a history of ill discipline, which, in 1858, provoked a second 'White Mutiny' with a strike by the Madras Fusiliers, the 1st Bengal Cavalry and other units who objected to being unilaterally transferred to the Crown's Army. This 'mutiny' gave rise to strong expressions of anti-crown sentiments that culminated in the worst excess by the 5th Bengal European Cavalry, who barricaded themselves in their barracks and abused their officers. Regular Army infantry and artillery surrounded the 'mutineers', who, after a week, were starved into submission. In the aftermath of this incident, the government once again attempted to gloss over it by acquiescing to most of the troops' demands. Only 2 809 troops elected to transfer to the British Army and 10 116 were transported back to Britain. When the troublesome 5th Bengal European Cavalry mutinied once again, the authorities proved less lenient and the mutiny was quickly subdued by a demonstration of force, followed by courts martial. The ringleaders of the mutiny were discharged and sentenced to penal servitude, but the leading mutineer, Private William Johnson, was executed by firing squad in 1860 (Brereton, 1986, pp 81-2).

Sykes's legacy does not appear to have had any substantial impact on transfer to Regular British Army. As late as 1871, the British Army in the East was still being described as 'a vast wilderness of ungodliness' (Anderson, 1971, p 54).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org