The South African

The South African

Red Cross/ ambulance emblem

Acknowledgements

This extract of Dr Charles Murray's diary was first published in 2000 in the South African Medical Journal (SAMJ), 2000, Vol 90, No 12, pp 1195-8. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of Dr Robert Murray in Melrose, Scotland, and Professor J P van Niekerk, Managing Editor, SAMJ. The editor of the Military History Journal appreciates the efforts of Professor Deon Fourie in arranging its re-publication in this journal.

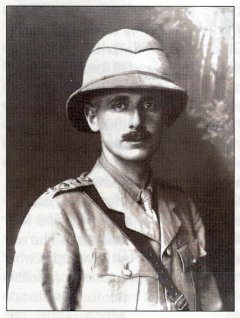

Capt (later Maj) C M Murray

(Photo: By courtesy, Dr R Murray).

Just twelve years after the conclusion of the Boer War, South Africa was taken by its leaders, ex-Boer generals Botha and Smuts, into what was to become the Great War, on the side of the British. This was utterly unacceptable for thousands of Boers who had engaged in a bitter struggle, against overwhelming odds, to prevent their country from becoming part of the mighty British Empire. Led by generals de Wet, Beyers and de la Rey, Lt-Col Maritz and Maj Kemp, they took up arms in a doomed rebellion, without proper weapons, equipment, or organisation, but, by the time they were defeated, the casualty figures exceeded those that would later result from the German South West Africa Campaign (Garson, 1962, p136).

Charles Molteno Murray, 37 years old, was a Kenilworth, Cape Town GP. His father was an Irish immigrant doctor; his mother, the daughter of the first Prime Minister of the Cape, Sir John Charles Molteno. In spite of having a busy and successful practice, with a surgical appointment at Victoria Hospital, Charles Murray volunteered for duty and soon found himself in the northern Cape, caring for the wounded and dying of both sides in the rebellion. He kept a meticulous record of his experiences, written on loose-leaf pages sent as letters to his wife, which were later bound into leather-backed diaries. These diaries were passed on to his grandson, Dr Robert Murray, who had them transcribed into modern format. They contain details of daily life in the midst of military action, and also insights into important and little-publicised events of the Boer Rebellion of 1914.

R I Murray, MB ChB (UCT), FCS (SA), FRCS (Edin), FRCOphth (UK)

16 Nov 1914. Tempe, Bloemfontein. Had a busy time. Warned in the morning to expect a considerable number of wounded from a fight at Virginia near Kroonstad. The day was spent in clearing the hospital of all those who were fit enough to travel or be sent to the convalescent hospital. Van Coller went over to Tempe to open the Military Hospital there for convalescents. 16 wounded arrived about 9.30pm. All were serious cases. One had been shot through the abdomen and was obviously dying from internal haemorrhage. I operated, but it was hopeless, and he succumbed about an hour later.

South African motor ambulance, c1914

(Photo: By courtesy, SANDF Documentation Centre).

This evening Col Brand was brought in by train suffering from acute appendicitis. We found it necessary to operate immediately. He is bad, as suppuration has already taken place, so that the operation resolved itself into clearing out the abscess cavity and putting in a drain. Col de Kock operated. The latter was at the Diocesan College with me in 1890-1894 and I had not met him since those days. Col Brand's condition is undoubtedly very critical and his loss will be much felt, as he is in command of all the Free State forces, and a very capable man. Turned in about 1.30am.

Dr C M Murray (right, behind driver) in his 'Valveless', a private motor car

which he took on the strength of the unit during the 1914 Rebellion.

The officer beside him is probably Capt van Coller.

(Photo: By courtesy. Dr R Murray).

17 Nov 1914. Today heard something of the fight at Virginia. De Wet with about 1 500 or more men tried to capture the railway station, which was held by about 250 of our fellows. They held out pluckily until reinforcements and a train arrived. The wounded men said the rebels were very badly armed. They were using all sorts of weapons, even shotguns, and had very little ammunition of any sort, but they were all splendidly mounted.

A man named van Niekerk, one of the rebel leaders, was brought in today. He gave rather an interesting account of how he was wounded. It appeared that he saw a body of men advancing, consisting of about a quarter of the number of his own troop. As they came up he recognised Col Toby Smuts, who had mistaken his (van Niekerk's) party for his own side. As soon as they came up van Niekerk drew his revolver with the intention of ordering Smuts to surrender, but as he raised his hand Smuts's son recognised his mistake and fired at him at twenty yards [18,3m]. The bullet passed just above his heart but does not appear to have done much damage up to the present. This occurred at Mushroom Valley where the first lot of wounded came from on the day of our arrival.

Mushroom Valley, 12 Nov 1914, was the scene of a crushing blow against the rebels, although it is simply described by one account (Davenport, 1963, p91) as 'a defeat' for de Wet, and by another (Garson, 1962, p 136) as de Wet being 'surrounded by superiorforces'. Charles Murray provides a considerably more vivid picture of the action.

22 Nov 1914. Last night we had a very interesting account of the Mushroom Valley fight from a Lieut Fraser, one of Sir John Fraser's sons, who took an active part asone of Brand's commando and was wounded. He had a very narrow escape. A bullet passed through his left arm, then through his handkerchief pocket without further wounding him. The same bullet then passed on and struck the man next to him passing in below his left arm and finally lodging in his spine at the level of the 9th vertebra, where we can see it with x-rays. The second man's name is Lieut Coetzee. He came off worst as one of his legs is paralysed. However both are getting on well now.

So far the papers have published very little about Mushroom Valley, so some account of it will be interesting. It seems that Col Brand's commando was given the billet of following up de Wet while Botha and the others went to other parts to cut off his retreat. Col Brand had about 1 300 men in his commando and carried out a very rapid journey, in fact they only rested for an hour at a time for nearly 3 whole days and nights. At the end ofthis they made a final march of21 miles [33,7km] and came on de Wet in Mushroom Valley in the early morning. The rebels were so confident that there was no one near that they had not even put outposts or sentries. The whole rebel laager was asleep when Brand's men opened fire and Fraser described a scene of the utmost confusion. The rebels had large numbers of horses, which they had looted, and these stampeded and the whole laager was a scene of the wildest confusion.

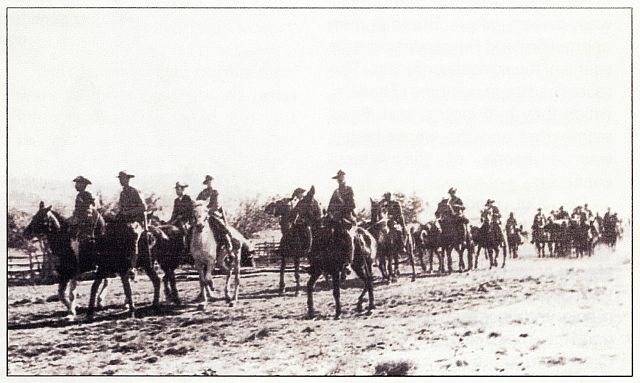

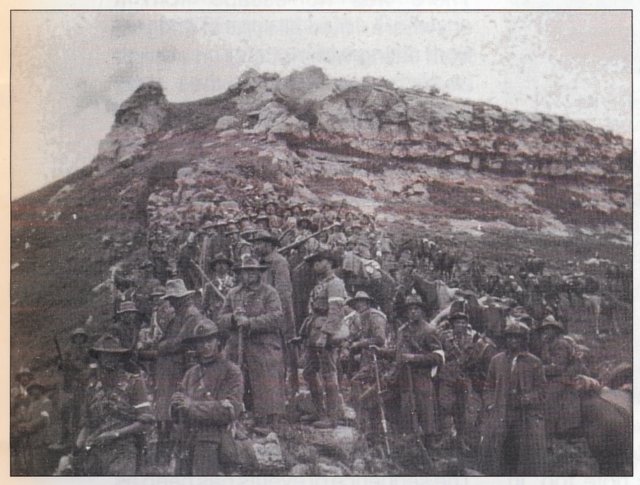

The mobilisation of Union troops to deal with the Rebellion

(Photo: By courtesy. South African National Museum of Military History).

De Wet made off and just managed to escape owing to Col Lukin's commando not having been able to get to its post in time. Fraser told us that his commando buried 62 rebels, and since then wounded and dead have been picked up in various directions. About 500 horses were captured and all their wagons, carts, stores and ammunition. The rebels were scattered in all directions, so that the defeat was much more complete than one had any official news of.

Capt Forbes, who came down with us and had been attached to Col Lukin, gave an interesting account of how the Colonel nearly lost his life by lightning. It appears that he went to the top of a kopje to reconnoitre a position, and, while there, a thunderstorm came up. When it passed over the kopje, Col Lukin had near him 2 signallers. One was operating a helio about 60 yards [55m] away and the other was standing about the same distance on the other side. They were all knocked down by lightning, and Col Lukin said he had hardly regained his feet when a second flash came and they were all bowled over again. This time Col Lukin was unconscious for about 5 minutes. One of the signallers escaped unhurt. Col Lukin had his breeches ripped down the side of his leg but was otherwise not hurt. When a search was made for the 3rd man of the party, the soles of his boots were found on the spot upon which he had stood, still occupying the same relative position as when the owner had stood in them. His body was lying about 10-15 yards [914m] away down the side of the kopje. He had a gash on the side of his head. His clothes were so torn that it was practically impossible to separate the fabric of his tunic and shirt from one another. The uppers of his boots were on his feet. All his buttons were gone. His body was marked with fine exfoliating black marks. Death was instantaneous.

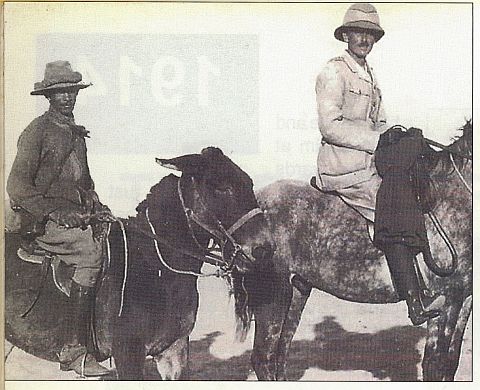

Dr C M Murray on the pony (right),

with his 'agterryer' seated on the mule on the left.

(Photo: By courtesy, Dr R Murray).

A young medico called Swanepoel was captured at Mushroom Valley and retaken later on by Botha. He said he was attending some wounded when he noticed that a flanking force was coming up, his own troops having already left the area he was in. He did not bother as he supposed the rebels would not interfere with him. He was rudely disillusioned however when he found they were firing at him. He said that they continued firing until they were within 15 yards [13, 7m], in spite of the fact that he was unarmed and bore a red cross on his arm. He said he expostulated and pointed at the red cross, but they only called on him to hold up his hands, which he refused to do as he said he was a non-combatant. One of them fired at him again at 15 yards, and missed him; at which Swanepoel called out if he fired again he would give him a thrashing. Swanepoel is 6ft 3in [1,9m] and broad in proportion, so how they missed him I don't know. He said that the rebels were armed with all sorts of weapons, including shotguns and even airguns. Most of their ammunition is sporting, that is to say the bullets are of the dum-dum type.

Among the last wounded (16 in number) 7 have shattered thigh bones and 5 smashed elbows. The wounds are very bad owing to the use of dum-dum bullets. We extracted a dum-dum from one case this morning. I have made friends with an old carpenter who is making wooden splints for me, and is much interested in the work.

The rebels are wearing their old defence force uniforms, and also have adopted the white badge on their left arm, which our troops had been ordered to wear in order to distinguish them from the rebels. They are looting and destroying all the farms of the loyalists and even wantonly destroying the thoroughbred stock and imported cattle and sheep. I think the rebellion cannot last much longer as they have no ammunition, and in the great majority of cases I don't think their hearts are in it.

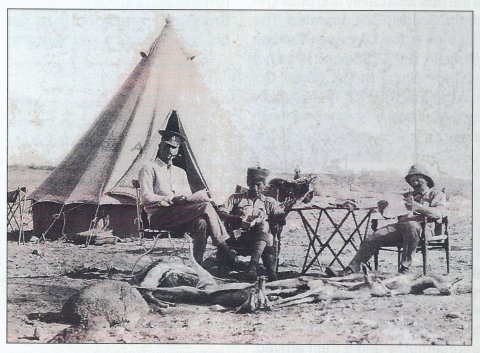

The officers' camp, with game for the pot. The officer seated on the left is probably Capt van Coller.

The folding chairs pictured here later came into Dr Murray's possession. (Photo: By courtesy, Dr R Murray).

24 Nov 1914. I had a chat with one of the rebels this morning. I have had all the rebels in one of my wards. He told me that he had been called out by de Wet, and that de Wet had told them all that they were simply assembling to show who had the greater following, Botha or Hertzog. On arriving at the laager, quite unarmed, this man was told they were going to fight the government and he must accompany the commando until he could get a rifle. He was one of the first to be wounded at Zand River near Virginia, though he never had a weapon in his hands.

He then went on to say that there were many rebels who had never intended to fight, and that the leaders had held back all information and that the great bulk were quite unaware of the amnesty (which had been offered to the rebels on 30 Oct by Smuts). One of de Wet's staff who has just been captured says that de Wet is furious with Hertzog, as he says he has let them all down and funked coming out, as he should have done. I think Hertzog comes worse out of this affair than any. To stir up men and egg them on to lose their lives in rebellion and then back out, is the limit of human meanness. So far the government have allowed none but the burgher commandos to do the attacking work and it is wonderful to see the enthusiasm of the men 'to wipe out the stain on the name of their race' as they put it.

The Umvoti Mounted Rifles after the Rebels abandoned the fight at Kestell.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

Although General Hertzog would not come out in open support of the rebels, he conspicuously failed to condemn Maritz's revolt, the only instance in which a Defence Force unit rebelled. This silence was interpreted by many as approval, and was probably viewed by Hertzog as being politically less damaging within his Boer constituency, than siding with the govemment (Duncan, 1915, pp230-2).

One of the Commandants in Brand's commando under my care did not turn back in storming a kopje until he had been shot through both arms and the abdominal wall. He said he had a good horse and was able to steer it with his knees until he got back to his own lines. It is wonderful to see where a bullet will go without killing. I have one man shot through the neck, who is slowly getting well. Another who was shot through one eye and out through the back of his head. This man is now quite well physically, but at times is very upset mentally. Several have survived shots through the chest, and what is more seem to suffer but the slightest inconvenience.

4 Dec 1914. The news of de Wet's capture came today. Feeling is very high here and I am sure that unless the government takes very strong measures against the captured rebel leaders, and de Wet in particular, they will lose a great deal in prestige, and equally in political ways. The feeling is that unless [the] rebellion is very firmly put down unrest will be roused again very soon.

The surrender of General de Wet.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANDF Doc Ctr)

11 Dec 1914. There are very few wounded coming in now, but a good many sick. There are generally 150-200 cases in our hospital. I have charge of the surgical wards and van Coller the medical. There is quite a lot of surgical work and I am getting a good deal of experience in cases one does not often come across in private practice. The day before yesterday the news of Beyers' end came, and the rounding up of the last rebel commando.

De Wet, broken-hearted at the death of his son Danie at the battle of Doornberg, was captured while on his way to join Maritz, while Beyers drowned in the Vaal River. These events effectively ended the rebellion, apart from Maritz's final attack on Upington.

16 Dec 1914. Since last writing I have been to Pretoria on business connected with our Brigade. I left on Tuesday morning and, travelling all day, reached Pretoria at about 1.30am Wed. It was a warm thundery sort of day with rain showers showing in various directions. All the bridges and culverts were guarded by pickets of burghers and DF [Defence Force] men. The turnouts of the burghers were most varied and remarkable. Men of all sorts of ages, each got up according to his own ideas. Most seemed to favour their old clothes. Some of the officers had parts of a uniform. One man had almost a complete uniform, the whole being finished off by the most jaunty looking little pale grey civilian hat. Another rather fine looking old man had on a grey tweed riding suit, with a Sam Browne belt, revolver and so on. Every sort of mixture of civilian and military clothing, and not the least amusing thing about it all, was that no one seemed to think they were the least bit funny.

It was a sight to make you realise what fighting really meant to these men. Out to fight and nothing else. No comfort, no show, just out to fight for their homes. All sorts of ages, sizes, shapes, and dispositions. Some gloomy, some cheery, but all in earnest about 'Onze Commando' and keen to show a commando could still do as well as ever commandos have done before. There was a pathetic note too, in such a scene. These were not professional fighters. Everyone had given up his means of livelihood to meet an emergency.

29 Jan 1915. De Aar. We spent all yesterday at De Aar. The evening of our arrival there the OC [Officer Commanding] of the Hospital came over to say he had just brought in a soldier whom the police had gone out to arrest. This man apparently managed to knock one man down and when running away was shot by another. The bullet went through his back and finally lodged in his abdominal wall. I went overto give a hand. The operation was a weird and wonderful performance. One wonders at the courage of some men, at undertaking things they can't do. However it was got through somehow and I imagine that the patient's fate is sealed as, having been fatally damaged internally, the operation could not have materially assisted him in any way. The less said the better.

2 Feb 1915. Upington. The last two days have been awfully hot. We had no special thermometer, but I found each day that my clinical thermometer, which I kept in my tunic pocket hanging in the coolest part of our carriage, always rose over 105 [degrees F]. Altogether I don't think I have ever experienced such intolerable heat. There was no escape from it anywhere. I tried all sorts of dodges, from sitting with nothing on at all to clothing heavily. No clothes at all was worse than any other dodge, as one's skin became burning dry and hot with no protecting layer of moisture. One comfort was that hot though the sun was, it does not burn one's skin like the coast sun does. One could walk about with bare arms and legs with impunity, and fear no serious sunburn if due care was taken. Upington must be a miserable place to live in.

Motor car used as an ambulance by the South African Medical Corps.

(Photo: By courtesy, South African National Defence Force Documentation Centre).

Today Maritz and 3 of his staff were brought in to arrange terms. The sequence of events has been as follows: Maritz sent a message in to Upington to tell them to remove the women and children, as he intended to attack the place the next day. This he did. Those who took part in this affair said it was quite the battle of the rebellion. Maritz had about 1 200 rebels who were all equipped in German outfit and had apparently been well drilled during their sojourn in GSW [German South West Africa]. He also had 200 Germans with big guns. Their guns considerably outranged ours, but in their anxiety to capture the situation they brought them unnecessarily close, so that our fellows in the CFA [Cape Field Artillery] were able to get within range, and once they did this their shooting seems to have been very good as they soon put one of the German pom-poms out of action and eventually did such execution that the rebels were forced to retire. One of the gunners told me that at the point he was in charge of, the rebels came up for the attack in splendid order and though he soon got the range and began putting shell after shell into the midst of them they never gave way, and when eventually it got too hot for them they retired in perfect order. I'm not sure quite what the casualties were but we had about 10 men killed and about 20 wounded, while I believe the rebels lost pretty severely as they left 18 dead when they were driven off. This failure to take Upington seems to have been the finishing touch for Maritz. It seems that the Germans do not mean to surrender with their guns and have probably trekked back to GSW. If this is the case I should say it means that Maritz intends clearing off with the Germans and leaving his men to their fate.

This was indeed to be the case. Maritz himself fled to German South West Africa, leaving his men to surrender. When the Union forces under Botha defeated the Germans in that country, he crossed into Angola, the dream of a 'trek to Pretoria to pull down the British flag and to proclaim a free South African Republic' shattered forever (Lange, 1916, pp44-5). All rank and file rebels taken prisoner were released in 1915; their leaders, in 1916. Only Jopie Fourie, a rebel officer who did not resign his rank and was responsible for 40% of the rebellion casualties, was executed (Rose-Innes, 1916, pp236-7).

Following the rebellion, Charles Murray served in German South West Africa, and then in France, seeing action at Delville Wood, the Somme, and Ypres. He was awarded the DSO and was twice mentioned in despatches. After the war he returned to Kenilworth and, like his father before him, served as President of the Cape Western Branch of the Medical Association of South Africa. (His grandson, the editor of this diary, was President of the Border Branch. Is this a unique triple?) Dr Charles Murray was awarded the association's Bronze Medal in 1945 for meritorious services as Medical Secretary, and at the time of his sudden death in 1950, he was Honorary Secretary of the Head Office and Journal Committee.

Sources

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org