The South African

The South African

C-in-C's Bodyguard headdress badge

(By courtesy, SANMMH).

About the authors

Janet Lourens was born in Wales and emigrated to South Africa in the early 1960s. She obtained an MA degree in History from the University of South Africa and, after many years in Reitz, co-authored a book together with her husband J A J Lourens, entitled Te na aan ons Hart - Aspekte van die AngloBoereoorlog in die Reitz-omgewing. The couple later collaborated on a second book, Voorvaders en Nakomelinge, Lourense, Van Niekerke, Du Plessisse en Prinsloos. Her love of the region and interest in her subject have led to further publications and continuing research into the history and genealogy of the area.

Steve Watt lives in Pietermaritzburg and is a specialist in military history, a tour guide and author of four books on the Anglo-Boer War: In Memoriam, The Roll of Honour Imperial Forces Anglo-Boer War; A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu-Natal (co-authored with Gilbert Torlage); The Battle of Vaalkrans, 5-7 February 1900; and The Siege of Ladysmith, 2 November 1899 - 28 February 1900.

INTRODUCTION

The entry of British troops into Pretoria on 5 June 1900, just five days after the surrender of Johannesburg, did not result in the termination of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) as the British public and their political and military leaders had sanguinely hoped. It ushered in a guerilla struggle which was to continue for another two years. In their attempts to subjugate the Boers, the British set about strengthening their control over the rural areas by occupying the smaller centres of population. The north-eastern Orange RiverColony, where Boer commandos were particularly active, became one of the focal points of the British initiative. By the end of 1900, Lieutenant-General Sir Leslie Rundle, based at Harrismith, had gained control of Senekal, Frankfort, Bethlehem, Lindley and Reitz. However, his troops could not venture outside these villages without running the risk of a sudden Boer attack (Grant, 1910, P 54).

In order to demonstrate that they were not about to surrender, the Free State burghers extended their field of military operations into the Cape Colony. This move was also designed to force Britain to dispatch troops to the Cape and so relieve some of the pressure on the Boer forces. Returning from his first attempt to invade the Colony in November 1900, General C R de Wet met with the Free State Executive Council in the veld near Senekal to discuss issues of military strategy. At the meeting it was finally agreed to dispense with the cumbersome wagons that inhibited the commandos' freedom of movement and to divide the burghers up into small highly mobile mounted units based in their home areas (Pakenham, 2003, p 351).

De Wet's strategy was to maintain a low profile while he prepared for a second invasion of the Cape. He made Commandant O A I Davel and his burghers responsible for the protection of President Steyn and dispatched them in the direction of Reitz while General Piet Fourie and Deputy Chief Commandant Philip R Botha, with their respective commandos, were instructed to patrol, independently, the area between Reitz, Lindley and Bethlehem. On 26 December 1900, De Wet left for the Heilbron district where, together with General C C Froneman, he recovered the weapons and ammunition captured and buried after the clash at Roodewal on 7 June 1900. These supplies were removed to a cave on the farm, Lovedale, in the Reitz district, where they were relatively easily accessible.

THE BRITISH ADVANCE

After working their way through the Ladybrand and Senekal districts in search of Boer fighters and skirmishing with Philip Botha's commando on 31 December 1900, Lieutenant-Colonels W L White and J S S Barker of MajorGeneral C E Knox's column, encamped at Lindley on 1 January 1901. They had a combined strength of 1 580 mounted troops, 228 infantrymen, nine guns and three machine-guns. Leaving Lindley in the early morning of 3 January 1901, they marched approximately 25 km eastwards towards Reitz, arriving at the farm, Plesier (110), in the afternoon (Grant, 1910, pp 54-5, p 59).

From here, Colonel White sent Lieutenant-Colonel D Tyrie Laing with 120 of his Commander-in-Chiefs Bodyguard ahead to reconnoitre the route to Reitz. The Bodyguard had only been constituted in November 1900 after Laing had received permission from Lord Roberts to recruit a force of 570 mounted colonials. The Colonel was an experienced soldier who had served with the 91st and 93rd Regiments, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He had subsequently settled in South Africa where he gained local military experience during the Matabele Campaign. A popular leader, he quickly received more than 1 000 applications from which he was able to select his force of mounted infantry (Stirling, 1907, p 225).

Colonial soldiers enjoyed respect among the military. In With Rimington, L March Phillipps states that one could not wish for better material or for keener, more loyal and more efficient soldiers. Many were veterans of various campaigns against the Matabele, Basuto, Boers and Zulu. They had the advantage of knowing the country and of speaking the indigenous languages. They were also 'accustomed in the rough and varied colonial life, to looking after themselves and thinking for themselves and trusting no one else to do it for them' (Phillipps, 1901, pp4-5). They were a voluntary force with troopers engaged for an indefinite term. If they disliked the work they could easily acquire a discharge and, on the other hand, the leader had a free hand in dismissing undesirables. As a result, the men were keen on their job and were seldom heard to grumble.

Lieut-Colonel D Tyrie Laing, leader of the Commander-in-Chiefs Bodyguard.

(Source: Wilson, After Pretoria [1902], p 235).

The Bodyguard left Plesier, marching eastwards along the valley of the Klipspruit which wound its way through the rolling grasslandsof the north-eastern Orange River Colony towards the Liebenbergsvlei River. Since it was high summer and the road ran alongside the spruit, the grass would most probably have been long and have provided cover for the enemy. Despite this, 'the party, regardless of rules and experience, was in close formation and without even ground-scouts' (Grant, 1910, P 55). From Plesier they marched about 6 km across the farms Helpmekaar (172) and Spijtfontein (220) before reaching Fredericksdale (510). Here they would have passed the burnt-out store of the Englishman, Stephen Murray Kingdon.

Only two weeks previously, British forces, implementing Kitchener's scorched earth policy, had arrived at Fredericksdale, the farm of George Frederik Rautenbach, who was away on commando (SRC, Vol 90, p 86). In an interview recorded many years later, his daughter, Susanna Magdalena, who had been a young girl of ten in 1901, related how her family's possessions had been set alight and how she, her mother and three sisters had been loaded onto wagons and taken to the concentration camp in Winburg. She also told of seeing Kingdon's store ablaze as they passed (Patriot, March 1998, p 8).

General Philip Botha, leader of the Kroonstad Commando.

(Source: Van Zyl, Die Helde-Album van ons Vryheidstryd [1944], P120).

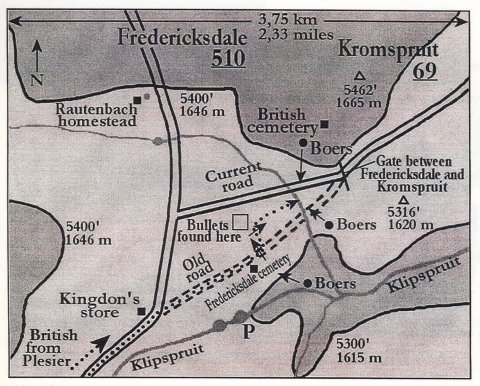

Up to this point, the route followed by Laing and his men would have coincided with the present-day road. Shortly after passing the store the old and new roads diverge with the old road continuing along the valley of the Klipspruit, crossing one of its tributaries flowing in from the north-west, then rejoining the present road near the boundary between the old Fredericksdale and the present-day farm, Dankbaar (68), originally part of Kromspruit (see map). As they marched along, Laing's men would have passed the old Fredericksdale cemetery on their right, where the two small children of Frans Hendrik Ebersohn and his wife Catharina Clasina Rautenbach were buried. Catharina Clasina, the eldest daughter of George Frederik Rautenbach, and her husband lived and farmed on this section of Fredericksdale until shortly before the Anglo-Boer War. Frans Hendrik was listed on the voters' roll of 28 September 1893 as a 'landbouwer (farmer) from Fredericksdale (Loock, p 34), giving credence to the statement of a Boer participant, Field-cornet Lukas Serfontein, that the engagement took place on 'Ebersohn' land (OM 4450/1, 'Oorlogsherinneringe .. .').

THE ENGAGEMENT AT FREDERICKS DALE, 3 JANUARY 1901

South of the cemetery, the ground falls away towards the Klipspruit while the old road ahead of the Bodyguard curved gently north-eastwards, descending gradually towards the drift on the tributary of the Klipspruit. With consummate skill, General Philip Botha, elder brother of Generals Louis and Christiaan Botha and father of General Manie Botha, exploited these natural features to ambush the approaching Bodyguard. Botha, whose commando consisted of about 80 burghers of the Kroonstad Commando, deployed a number of his men along the Klipspruit where they were hidden from the approaching Bodyguard by the fall in the ground and by the long summer grass. Anticipating that the British would move off the road to their left to gain protection from the shoulder of land dividing the valley of the Klipspruit from its tributary, he placed another group of burghers on the hillside to the east, where they would have an unimpeded view of the enemy.

Everything worked according to plan and shortly after passing the graveyard, the Bodyguard was subjected to a volley of rifle fire from the direction of the Klipspruit. The troops barely had time to recover and regroup to the left of the road when a 'perfect tempest of bullets' (Wilson, 1902, p 235) ripped into them from 550 m away on the rising ground to the east of the drift. Laing was one of those wounded in the initial attack, but managed to maintain control of his men. He mustered his troops with the intention of launching a counter-attack but his efforts were stymied when another group of burghers, judiciously deployed by Botha on higher ground to the north-east, opened fire. The fury of the exchange left behind a wealth of Lee-Metford and Mauser bullets which were later unearthed by Casper Bester and his nephew, S C C Bester, who, between 1920 and 2006, lived and farmed on the part of the old landholding of Fredericksdale, now known as Bridgerule (193).

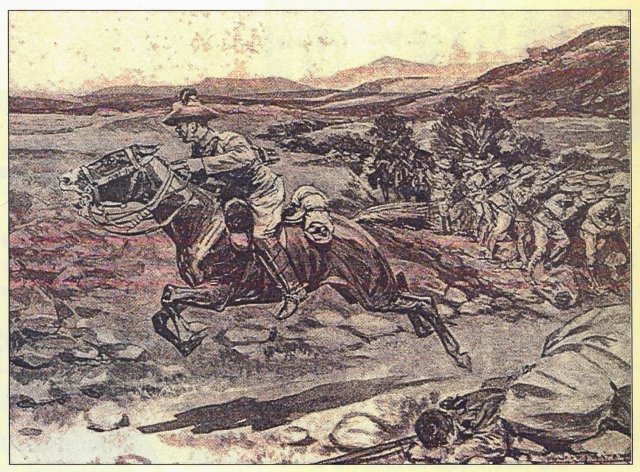

Botha, having foreseen that Laing might seek assistance from the main column under Colonel White, which was only 6 km away at Plesier, commanded the burghers who had launched the initial attack from the Klipspruit to cross the road and take up positions at the rear of the Bodyguard. Laing, then surrounded on three sides by Botha's commando, was faced with the option of continuing his defensive action or surrendering. He decided to fight on, probably in the hope that Colonel White's column would eventually come to his assistance. In an effort to strengthen his defensive position, Laing ordered his men into the bed ofthe tributary where the eroded banks ofthe spruit to the north of the drift provided some cover. They put up a brave and determined defence which only faltered when Laing was shot dead with a bullet through the heart. The Boers, pressing ever closer, poured a deadly fire into the defenders. At this critical juncture, Lieutenant Bateson courageously dashed out of the fray, mounted his horse and rode through the encircling enemy, taking the news of the Bodyguard's plight to Colonel White. White immediately sent a relief force, but, by the time it arrived, Laing's men had surrendered and handed over their arms to the Boers, who had already left the scene (Wilson, 1902, p 235; Journal of the Principal Events ... , 1901, January). The South African Field Force Casualty List records that five men - Lieutenant H H O'Flaherty, Corporal Phillpot (22202) and Troopers J Hett (22699), T Foy (22431) and D Kileher (22705) - were taken prisoner but were later released and rejoined the Bodyguard.

Map showing movements of British troops and Boers during the engagement at Fredericksdale, 3 January 1901.

(Map prepared by J A J Lourens, based on Map OM 4128/0range Free State, Reitz, Sheet South, G-35/W-III).

CASUALTIES

Altogether, 21 officers and men of the Bodyguard, including Lt-Col Laing, were killed or mortally wounded. While the injured were evacuated to Reitz and Heilbron, the dead were buried close to the scene of the action to the north of the road and against the boundary between the old Fredericksdale and Kromspruit (69) (see map). J J G Bester, then a young man in his thirties, recalls that in August 1965 he and four or five of his labourers exhumed the remains in the presence of a British official. Bester remembers that, after working throughout the day, they had exhumed the remains of about eight soldiers in a mass grave and one man buried at an angle of 90° to his colleagues. All the dead of the engagement were eventually re-interred in the heroes' acres at either Reitz or Heilbron. Buried at Heilbron were Lieutenant-Colonel Laing, Captain A Butters, Lieutenants S W King and F C von Schade, Corporal A L Stanton (22735) and Trooper T Cooper (22413). The name of Sergeant-Major J Ramsay (22753) also appears on the monuments in Heilbron and Reitz. It is uncertain where his remains are actually interred. Corporal L Stephan (22212) and Troopers W Barrett (22405), H J Blenkinson (22739), E J Divine (22424), J Godden (22541), W A Greer (22432), J W Kennedy (22448), F Kingdon (22447), J Matthews (22560), T Miller (22571), SParks (22362), W Rennie (22582), D E Saddler (22213) and W Wood (22483) were buried at Reitz. A further thirteen men of the Bodyguard suffered serious wounds while twelve received minor injuries (South African Field Force Casualty List, pp 101-2; monuments in the town cemeteries of Heilbron and Reitz).

On the Boer side, only one man died (OM 4450/0, 'Oorlogsherinneringe ... '). He was the 29 year old Christoffel Johannes Smit, son of Andries Adriaan and Cecilia Helena Christina Smit of Lindley (MHG, S2822). Where he was buried and how many of his fellow burghers were wounded remain unknown.

'Lt Bateson's Daring Ride'.

(Source: Wilson, After Pretoria, [1902], p 234).

CONCLUSION

Within the context of the war, the action at Fredericksdale was a minor incident, but, in terms of casualties, it was the second most important engagement in the Reitz area, after Graspan (6 June 1901). Philip Botha's leadership provided a fine example of guerilla tactics. Having recognised the opportunity occasioned by Laing's relatively isolated position, he launched a surprise attack using his innate military skill and knowledge of the locality to inflict a sharp defeat on the Bodyguard. His success illustrates how the hit-and-run strategy employed by the Boers enabled them, despite their limited manpower and inadequate infrastructure, to resist a much larger force of predominantly professional soldiers in both disputed territories for two years.

The engagement at Fredericksdale remains relatively unknown and the information available misleadingly asserts that it took place on the farm Kromspruit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Janet Lourens would like to thank C H Bester for clarifying the route of the old road and indicating the position of the drift, S C C Bester for permission to visit the site and to view the graveyard and the position where the bullets were concentrated and J J G Bester for sharing his reminiscences of the exhumation of the dead. Their information has enabled the authors to construct a more accurate picture of the engagement. The contribution of J A J Lourens in preparing the maps and illustrations and proofreading the article is much appreciated.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org