The South African

The South African

Alan Cockrell is a freelance writer, a retired USAF Lt Col, and a commercial airline captain. He is the author of Tail of the Storm, a memoir of the Persian Gulf War.

World War, 1914

Historians of the first air war remind us that a pilot's life expectancy was a matter of mere months, if not weeks. But the truth may well be that many of those First World War airmen survived to find their way back to the lives they had left behind, unheralded in the shadows of those who went down in flames, yet forever changed. Charles Wilton of Durban, South Africa, was one. The war changed him so profoundly that he did not want to go home. Perhaps he found himself exactly where he had secretly craved to be.

Charles Wilton was born in Melbourne, Australia, on 29 May 1891. Later, his family moved to England and, finally, settled in South Africa. Tall, thin, and athletic, 'Charlie', as the family called him, hungered for the speed of his motorbike and the taste of living on the edge. The excitement of wind in his hair and the risks of the road must have balanced the tedium of his job as an electrician. When the British Empire went to war against the Kaiser, he saw an opportunity for adventure while serving his country and King

. Wilton joined the South African army engineers in 1914 to fight the Germans in South West Africa (presentday Namibia). He never saw combat and returned to Durban, disappointed. The following year he paid his own passage to England and enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). He promptly applied to be a pilot, but his application was rejected. He re-applied and wrote to his older brother, Percy (whom he called 'Perce'), back in Durban, that he was 'on thorns waiting for the result. If it goes through, I am going to be the happiest of beggars living.'

Flashy fighter pilots have captured the public fancy since the first propeller swung in anger, but Charles's letters give us a unique glimpse of the First World War bomber pilot. They reveal a rare insight into airmen's lives in the 'Great War' and discredit many myths and perceptions resulting from decades of movies and tales. True to the persona of combat pilots over the ages, Charles was cocky and swaggering even as his second application was still being evaluated: 'Guess it won't take me long to loop the loop ... Don't think I am going to break my neck ... Just you fancy me aloft on my own. If all goes well hope to apply to a scout squadron, with a "bus" doing 150 an hour!' He was probably referring to the Airco DH-9 aircraft.

Airco DH-9 2-seat bomber in flight

(Photo: By courtesy, Alan Cockrell, Huntsville, Alabama).

The busy activity of war preparation clearly excited the young Charles Wilton. In an undated letter, probably penned around August 1918, he wrote from South Norwood near London: 'You just ought to be here, Perce, and hear the engines going from daylight to dark. One continual hum and buzz. They loop and twist and turn.' But along with the fun and excitement came grizzly visions of violent death: 'Two fellows went up last night, looped twice, did a dive ... sidesliped to the ground and burnt to death. Pretty rotten, you know.'

Finally the RFC called him to London to take a physical. It sounded more like a modern sobriety test. 'Well, Perce ... just try and hold your breath for 60 seconds and also stand on one foot with your eyes closed for 35 seconds.' He told Percy he had passed the physical and was awaiting orders to go to Oxford to study 'engines, fittings, etc, also to learn wireless. I will feel some man that day. But the great time will be when I start flying and learn bomb-dropping and machine-gun fighting and [aerial] photography. Then I will be as happy as a bird. Barring accidents of course.'

Before his first flight Wilton had already charted his future. 'If I get through this war alright, Perce, I am going to take up flying as a profession.' He wrote that he was not interested in going back to electrical work. 'The pilot's life is not a tremendously long one. But you know me, Perce, I am not the exceptionally brave or daring man but I want the right to get there and take my chance with the boys who are doing it. I can't stick behind in a comparatively safe job while others are at it hard, fighting for us. I must be right there, and right there I will get .. .' He continued, with a Tennysonian twist, admonishing his brother back home: 'Jump for the highest you can get and you won't go far wrong. It is better to chance it than never to have chanced at all.'

Flight training

The fledging airman passed his physical and was accepted into the RFC. In late 1917, he wrote to Percy about the rigour of his academic schooling. He studied three different engines, the 100hp Monosoupape rotary, the water-cooled 120hp Beardmore six-cylinder, and an eight-cylinder water-cooled engine. 'We have to know every mortal thing about them and have to sketch parts .. .' He was also required to sketch schematic diagrams of instruments. He explained to Percy, ' ... an aero engine ... going 1 200 to 1 400 rev[olution]s per minute, is going some. Eh!'

'Another cheerful subject is bombs. We learn all about two bombs. One is 201b, the other 1121b. Another subject, two machine-guns. One is the Vickers Maxim and the other is the Lewis Machine-Gun. Have to know every part, and there are over 60 parts in each.'

Surprisingly, Charles Wilton and his fellow RFC cadets were even taught the intricacies of rigging and covering. 'You learn how to splice seven-strand cable, how to cover the planes [wings] with fabric. What each wire and strut does, its name, how to attach the planes to the body and how to true them so that the machine will fly level in the air without touching the controls.' These were not subjects that endeared themselves to the young cadet, who was aching to get into the cockpit. 'It is a rotten, difficult subject, Perce, and I don't like it at all.' He and his classmates also learned how to read tactical maps and direct artillery from the air.

The young pilot cadet passed his examinations, which lasted two days. While waiting in London for his assignment to France, he ran short of cash. He asked his mother to wire him £25. After explaining the paltry RFC pay scale to Percy and the demands on his purse, he admitted, 'It goes against the grain for me to wire for money, Perce, but I was absolutely in the cart-broke. Of course, you might know I have never been anything other than broke.'

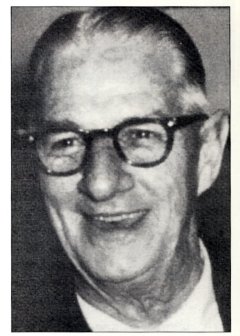

Lt Frederick Charles Wilton, DFC, RFC, 1918

(Photo: By courtesy, John Wilton, Spartanburg, South Carolina).

After a month's leave in London, Charles reported to his training squadron at RAF Catterick in north-east England. (By then, in 1918, the RFC had become the Royal Air Force). In February 1918, he wrote to Percy that 'It is much better being an officer than being in the ranks ... The officer's mess is much more swanky.' Dining with majors and colonels was a novel experience for him, and he might have felt out of place, but this was not the case. 'I'm as good as they are. [But] as a sergeant I had a good time and would not mind being one again'. Continuing in the same letter, he writes, 'Now comes the interesting part, flying. At last I have flown my own machine today ... Took her up and landed her about six times. Spent about 1 1/2 hours in the air on my own. Still I want a lot of experience yet.'

Percy had to read on to find that Charles was still with an instructor, not yet solo: 'I sat in the front seat, the instructor in the rear.' In his letter, Charles Wilton revealed that inter-cockpit electronic communications had its beginnings in training in the First World War. 'I have a telephone receiver on my head under my helmet.' he explained, 'At about 1 000 feet [304m] [the instructor] told me to take the control lever or joy stick as we call it.' Charles did not say what kind of machine he was receiving his training in, but it is likely that it was an Avro 504. After two hours and forty minutes of instruction flying, the instructor climbed out of the aircraft and told him, 'Now take her up, fly around the aerodrome and land her yourself.'

With a youthful cockiness typical of military flight trainees, Wilton referred to the trainer by its nickname, 'Bus', as if he had been flying it for years. 'I didn't think twice, Perce,' he wrote. 'I went off on my own. It was great to sit up in the old bus and look down on everything from 2 000 feet [608m]. I enjoyed myself and then came down to land. I felt a bit dubious because you have to shut off your engine and glide down, then about six feet [1 ,8m] off the ground, flatten out and as soon as you lose flying speed you feel her begin to sink. You then pull the joy stick back into your tummy and she touches down and runs along the ground.'

'Am going to put in another hour or two solo and then I am going to loop the loop .. .Requires a little nerve to loop the loop first time. Also to stunt close to the ground.' Catterick's safety record must have been improving, because Wilton wrote that only two had been killed in the last fortnight and one had been pretty badly burned, stunting close to the ground, no doubt.

Airco DH-2 trainer aircraft (Photo: By courtesy, Alan Cockrell, Huntsville, Alabama).

Charles Wilton and his classmates flew about twelve more hours before changing to a different trainer, which he did not describe in his letters. In the new aircraft, they trained with machine-guns, bombs and aerial photography. They dropped bombs from altitudes of 6 000, 10 000, and 15 000 feet [1 ,8km, 3km and 4,5km respectively). 'Some height, eh?' he bragged to Percy, 'The machine is a big beauty doing 120 on the level. Some speed too!'

Charles concluded the letter by telling Percy that his pay would increase to £40 a month when he finished training, but until that time, perhaps his brother might convince his mother to send him another £25?

In action in France

Lt Wilton's next letters were from an undisclosed location in France. His new post was 98 Squadron, RAF, a bomber unit flying DH-9 aircraft. Continual bad weather thwarted his first chances to get into the 'show'. The grounded pilots suffered from boredom and bad food. 'We have absolutely nothing to do. Can't even get a newspaper here. Would very much like a few books to read.' They were too far from a town to pay one a visit, but the weather did little to dampen the young pilot's will to get into the fight: 'Wish it would clear and we could then leave Jerry with a few pills to digest,' he wrote.

Strangely, Wilton does not describe his first combat mission to Percy, unless he did so in a lost letter, but he explains what it was like in general terms to fly in battle. 'This may sound strange to you but most of the fighting in the air is done at 17 000 to 18 000 feet [5,2km to 5,4km] up. The old Hun [German] sits up in the sun and watches us go over but seldom attacks until we drop our bombs and commence to turn round and then he dives and one hears "rat-a-tat" everywhere ... all we do is let our observers pop away at them and we keep formation.' The Germans' tactical behaviour described here contradicts their later practice of striving to destroy attackers before they dropped their bombs. Both sides soon realised that forcing an attacking bomber to jettison its heavy bomb load before reaching his target, in orderto improve defensive manoeuvring, was a victory of sorts.

'We fly very close together so that when the Hun dives, all the observers can bring their guns on to him.' In the DH-9, the observer sat aft of the pilot, facing to the rear with his mounted machine-gun. 'Of course, if 20 or 30 attack we'll keep as good formation as possible under the circumstances and if you get split up, make a dog fight of it. Each of you goes for the nearest Hun. Great life, Perce. The excitement is great ... Funny, but when the Hun is sending up plenty of archie [ie, anti-aircraft fire] we don't mind so much. It is when everything is quiet then we know that Huns are about and keep our eyes skimmed in every direction. The Huns use high explosive shells and you can see them bursting all around, below and above you, and also hear them bursting. Still, we sideslip, climb and turn to dodge it and although the planes etc get pieces through them, it is seldom one gets a direct hit. When they burst you see a cloud of black smoke and sometimes hear a piece whizz by. Still, it is fine. You can see the war below and on clear days you can see the whole of the back area, see his [the enemy's] trains and transport, etc.'

'Would sooner fight this way than any other. Besides we [the bombers] go umpteen miles behind the lines too, further than most machines do. Even if I never see a lot of towns from the ground, I will have seen them from above ... Raining like old boots now. Pretty rough on the boys in the trenches. When it rains they have a bad time.'

In May 1918, Charles responded to a letter from Percy that took over two months to reach him from South Africa: 'Most of the fighting here is done at 17 000 to 18000 feet [5,2 to 5,4km] although we cross the [battle] line much lower than 18 000 for the sake of quickness. When on a single show [mission] we get as high as 20 000 feet [6km] if you can get there.' Earlier, he had written that the aircraft were often fitted with oxygen tanks, another early innovation that allowed pilots to remain alert at high altitudes. 'I wish you could have seen some of our machines. You would be very surprised at the number of guns etc in the various fittings.'

'When over the lines and the Hun shells are all around you and you hear and see them bursting it makes you just love the game. I have seen us going through when the air has been thick with black puffs of smoke and we dodge here and climb and slip and climb. Man, it just makes you love it. He [the Hun] certainly puts stuff up at us. And we come back with planes torn and pieces in the machine, etc, but ready for the next show. Just fancy us-about 12 or 14 machines in formation on a beautiful morning going over [the German] lines at 05.30 and when we get to our objective he knows we have been and also knows that if the weather is at all permissible we will be over again ... I ramble a lot about our work, Perce, but if you only knew how great it is to be up there and doing things, you would not at all be surprised that we think a lot of it. The boys too are a fine bunch.'

'Had an engine go dud the other day about 10 miles [16km] over so I dropped the eggs and turned back and had to land about 100 miles [160,9km] from here. Had quite a good time though.'

'Glad to hear your business is good, Perce. I reckon it is about time you had some luck. Don't know what I will attempt when the war is over. It would be quite a good scheme to stay on in the RAF as a pilot. Have no fancy for going back to electrical work. Reckon I have forgotten all about it now.'

Leadership in the sky

Wilton's next letter, undated, was short. By then, he was obviously becoming a seasoned combat veteran. Unless recorded in earlier lost letters, this was the first mention of his air-to-air kills: ' ... we have been busy. Went about 200 miles [322km] over and laid some eggs from 1 000 feet [304m]. Then we gave 'em beans with our machine-guns. Travelled along the roads and shot 'em up in all directions. We bumped lead into a battalion of Huns on the road. Anyway, we all got back safely. They did fire some stuff at us from the ground though, balls of fire (flaming onions), archie, tracer bullets from machine-guns. They even turned their field guns on us, we were so low. I was glad when we got back anyway because it was a risky job indeed. I did two more shows that day from a very low altitude and got my sixth Hun. Sent him down in flames. Unfortunately, we lost three machines that day. That means three pilots and three observers. We also got four Huns. The chief thing was we did the job we went overto do and were highly congratulated.'

Wilton's mounting experience had, by now, vaulted him into a leadership position in his unit. 'I led the squadron over the other day. About 12 machines. When about 8 miles [12,8km] over, about 30 Huns attacked us. Believe me, we had some fight. They got two of ours. They attacked us from all parts. Next time we went over they attacked us again but our scouts [fighters] were about and I witnessed a topping fight. It was great to see a fight from 14 000 feet [4,2km] in the air. I was congratulated by the general for bringing my fellows through the fight the other morning.'

Lt Wilton (seventh from left) with his squadron-mates in front of a DH-9 aircraft, 1918. (Photo: By courtesy, John Wilton, Spartanburg, South Carolina).

Other sources ('Aces of WWII', http://www. theaerodrome.com/aces/safrica/wilton. html, accessed on 11 Oct 2005, 18 Jul. 2006,) indicate that Charles and his observer were reported missing on 12 June 1918 but returned safely. A month later, he was forced down and, a week after that, during a raid on the Hirson railway station, he was shot up by a German Pfalz.

A German Pfalz 0111 (Photo: By courtesy, Alan Cockrell).

On 10 October, Charles wrote to Percy after two weeks' leave in England. He said he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on 17 September 1918. 'I have not had the medal presented by the King yet ... I must be one of the first South Africans to receive it. At any rate, the first Durbanite.'

Percy had read in the Durban newspapers that many Allied aircraft were missing or shot down on a single day. His brother confirmed it: 'Well I know it, Perce. That day was the commencement of the battle of the Somme.' He wrote that he went over 'the Hunland' three times and had completed forty missions over enemy territory, about 100 hours in total.

Charles Wilton was expecting to be transferred back to England in one month, hopefully to a flying training position, but he told Percy it could be some 'comic job'. He wrote, 'I have not mentioned it before, Perce. I am going to try and remain a regular officer in the RAF. I could never settle down to a life of everyday sameness again. The time I have spent in the army I have forgotten all about electricity. My nerves are still good and I think that, for another few years, flying would do me good and suit my temperament. Try as I may I can never save money. Even now I spend money as fast as I get it ... Anyway, Perce, I think it will be best for me to stay in the RAF if I can arrange it. You say I ought to keep a diary. Well, so far I have not got one. We have so many scraps and different experiences and we simply take them all as they come. I have not shot down any more Huns lately. I think I had told you I had got seven Huns though up to the present most of them went down in flames. Nearly bought it the other day. We had been strafing a Hun aerodrome and on our return the Huns shelled us very heavily with archie. One shell burst right in front of me and riddled the machine. Still, I have been on quite a number of shows since. We did a real good one the other day ... It looks real great to see your bombs go off and then clouds of smoke from the burning wreckage ... Now that Germany is asking for an armistice and we have been advancing so well I don't think they can last so very much longer.'

Men actively engaged in combat rarely desire to see their name in newsprint, for fear the enemy might use it against them if captured and, in this, Charles was no exception. In a letter dated 31 October 1918, written on grubby paper, he berated his brother for wanting to take his letters to the local newspaper: 'I would very much rather you did not, Perce, because I don't want any publication. You are the only one to whom I write about our experiences here. It is good to write to you about it. Sort of gets something off my chest. If you do publish anything, keep my name out of it.'

'Guess we had the toughest fight I have ever been in yesterday. It was a very big air battle. One of the biggest I have heard of too.' [He may have been referring to a raid on the Mons railway station on 31 October 1918. His plane was badly shot up but he scored two kills.] 'We went over about 15 miles [16,6km]. It was a beautiful day. You could see for miles. Going in, they shelled us very heavily and accurately. Sky was full of smoke from the burst of their high explosive shells. That suddenly ceased and we mixed it. Twenty of us and 50 of them. It was some fight. The sky was full of machines at about 12 000 feet [3,6km]. Bullets were singing everywhere ... Machines were diving, zooming, turning, and twisting in all directions. About 20 or 30 came at us directly ahead. I opened fire and sent one down in a spin and he then broke into flames. My observer was tending to about five on my tail. Agood burst into one of them and down he went too, but apparently he regained control and landed. The fight lasted about 20 odd minutes and the final official result was nine of ours went down and we claimed 13 Huns. I reckon we got more Huns than 13. Some of our fellows who went down must have accounted for quite a few before they went down. It was wonderful sight, Perce.'

Another sight was not so wonderful, however: 'One of our fellows went down in flames alongside me and I can assure you the sight rather upset me. Seeing Huns go down in flames does not have the same effect on me. I had Huns glued to my tail and could not shake them off. Every movement I made they copied and it beats me how I got out of it. It must have looked a wonderful sight from the ground.'

Without a break in the paragraph, the young pilot then changed subject from the killing of Huns to the quality of his accommodation: 'We have moved into another chateau and it is a most magnificent house. Beautiful staircase and furniture. Hun generals and staff people used this house and they have not damaged it much. I am very fortunate. I have got a huge Queen Anne bed with canopy covering. No sheets though.'

A view of the frontline

Charles managed to get close to the front lines on the ground, for reasons he did not disclose, and he was stirred by what he saw: 'I have been to the lines twice within the last 24 hours and believe me Perce if you could see the women and children and old men going back to their homes. Some of their homes are a heap of bricks and dust. We were within 1 000 yds [914m] of the line and very nearly ran into some shells. Quite exciting. The Bosch [German] has certainly blown up roads, railways and some material. He has taken miles of copper wire from the electric poles. Civilians are living within shellfire range and take everything calmly too. PS. Have just had dinner. Rabbit and carrots! Ugh!'

Charles Wilton's final surviving war letter may have been written after the Armistice. 'We don't care so much about the medals as long as we do our job and help the lads who stick in the trenches. Since I got yours and Mum's letters though, I am real pleased that I won it [the DFC] because you are all so jolly bucked about it at home. As one of our fellows told me some time ago: You don't think too much about it, but ... you know how pleased it makes 'em feel at home .. .'

After the Armistice

In November 1918, the London Gazette published Charles Wilton's DFC citation:

'A fine fighting airman, who has destroyed six enemy aeroplanes and driven down another out of control. He has taken part in a number of long-distance bombing raids, and is conspicuous for his determination to reach the objective as well as for his skill in successfully bombing the same.' ('Aces of WWII', http://www. theaerodrome .com/aces/safrica/wilton. html, accessed 11 Oct 2005, 18 Jul 2006).

'Can't say what my plans are forthe future,' Charles wrote, 'I certainly don't feel like coming home and settling down to the old life of wiring, etc. In fact I don't intend to do it ... I am going to try and remain in the RAF as a pilot ... If I don't remain in the RAF, I am trying to get a pilot's job somehow and in any part of the world too ... I have a good record as a pilot and am considered a first class pilot so you need not be afraid to recommend me. Also I am a memberofthe Royal Flying Club ofthe UK'. As in all his letters, he ended with 'From your loving brother, Charlie.'

Sadly, Charles Wilton was not able to stay on in the RAF after the war, nor did he find a pilot's position in the civilian world. He returned to Durban and resumed his occupation as an electrician, eventually becoming a successful electrical contractor. He married Maude Reilander, and they had one son, John. Charles volunteered again when his country needed him and served in the South African Air Force during the Second World War. He wanted to fly but they deemed him too old and assigned him a desk. He continued to flourish as a family man and business man until his death on 7 July 1958.

Mr F Charles Wilton, 1958 (Photo: By courtesy, John Wilton).

Rev John Wilton, Charles's son, told the author one of his father's favourite stories. After the armistice Charles's unit was ordered back to England. Each pilot was told to fly his aircraft back as weather and duties allowed. Charles was concerned about the trip because he had never flown across a large expanse qf water. It presented navigation challenges for which he had not been trained. He swallowed hard and aimed his ship westward across the Channel. After a nervous crossing, he landed on British soil. He turned and was surprised to see many of his squadron-mates landing behind him. They approached and told him they were glad they had followed someone who knew his way!

Charles's letters cast a new light on early military aviation. They reveal that many innovations, commonly thought to have originated much later, were rooted in history's first air war. Among them were initiatives in aviation physiology, the use of supplemental oxygen, the evolution of fighter escort for bombers, close air support, deep interdiction operations, aerial reconnaissance, inter-cockpit communications, and comprehensive training programs. His descriptions of high tempo air battles prove that the early military pilot, relative to the technology and collective experience of the time, needed as much knowledge, skill, and situational awareness as his modern counterparts. More importantly, the letters show us the soul of the man inside the cockpit. Wars are fought by people, ordinary people like the electrician, Charles Wilton. Wilton may have looked back on that one year as the pinnacle of his life, but the free world needs its warriors back alive. It needs their skills, wisdom, and caring. It needs their legacy of service and love for freedom, country, and family. Charles Wilton and other citizen warriors served all of those needs, just as war veterans still do today.

Sources

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org