The South African

The South African

In Military History Journal, Vol 13 No 5, June 2006, pp 168-73, the first part of Arthur Candy's story of the Second World War was published under the title 'Maritzburg to Mareopolis - The making of an amateur artilleryman'. In Military History Journal, Vol 14 No 1, June 2007, pp 22-31, his story continued under the title 'Amateur Artilleryman in the Desert, 1941-2'. This brought us through the Desert Campaign in North Africa to the disaster of Tobruk, 21 June 1942. Facing the crack armour units of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions, the fortress of Tobruk fell and, with it, most of its 33 000-strong garrison force. In this, the first of a two-part series, Arthur Candy describes his war experiences after Tobruk, as a prisoner of war behind enemy lines ...

The morning after [the surrender of Tobruk], all officers were bundled into five-ton trucks, which trundled off along the road to Derna. At this small, historic town, we debussed and spent a cold and uncomfortable night in the local cemetery. It was uncomfortable because the ground between the graves upon which we tried to sleep was coarsely gravelled and the Senussi soldiers, now in charge of us, were uncouth, unable to communicate and particularly trigger-happy. Any movement spotted during the night drew fire from a sentry. A padre had a bullet neatly part the crown of his cap, fortunately not touching his head. The small escort body accompanied us the following day to Benghazi, during which journey we passed through several small Italian villages, set among well-cultivated areas. In Benghazi, the prisoners were incarcerated in a large prisoner-of-war camp. The food was 'plain' and meagre, consisting of a small bowl of soggy rice and a portion of tinned meat, which, according to someone versed in such matters, was tinned horse meat.

The next move was a brief, hair-raising experience in which we travelled to Italy in cargo transport planes. The trip was tense and uncomfortable; physically uncomfortable because there were no seats in the wood and canvas aircraft, so we were obliged to sit on the floor, and there were no windows; and mentally uncomfortable because we knew we were flying through air-space frequently patrolled by Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters based on Malta and always looking for juicy enemy targets. Being the first air travel experience for many of us, and being undertaken in these hazardous circumstances, the trip was a tense and silent one. As our 'crate' touched down on the airfield at Lecce in the heel of Italy, a great communal sigh filled the cavity ofthe aircraft. Even the lone armed Italian escort was relieved.

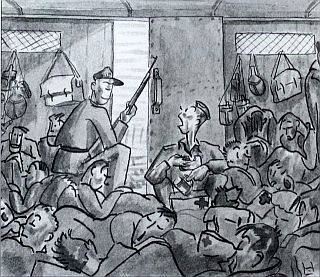

'Of course, our passenger service in England's nothing like this ... '

Cartoon by A F Hay, Clink, POW newspaper established by

A F Hay and E G Currie-Wood in POW Labour Camp No 3657 in Bad Tolz, Bavaria.

(By courtesy, South African National Museum of Military History).

After the surrender ot Tobruk on 21 June 1942, the 'Desert Fox', German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel,

enters the important North African harbour town. (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

POW IN ITALY

Stepping out onto the wide expanse of emerald green grass was, despite our situation, a wonderfully pleasant surprise after two years of seeing nothing greener than dusty olive-coloured salt bushes. We were led to an empty hangar, given a few bundles of straw to soften our stay on the cold concrete floor, and left with guards at the door. Here, I was joined by a companion who furtively withdrew, from his greatcoat, a bottle of Marsala wine. Whence could such an unlikely product have come? The question was never asked, but my guess was that it must have involved some sort of bribe. A third man joined us and, in a twinkling, the emptied bottle was discreetly discarded. We slept well that night, in spite of the dusty straw. The following morning, a few hours of travel in the luxury of first-class train carriages, guards included, brought us to Bari. After a march through the streets of the town in view of gaping civilians, the barbed wire gate of the transit camp closed with a slam behind us.

The camp was small and cramped and the food was thin and of poor quality. After a week or so under these conditions, the camp's population grew hungry, lean and mean. It was very clear that the authorities had not expected the sudden arrival of so many prisoners. Persistent complaints by the SBO (Senior British Officer), a senior officer appointed to represent the prisoners, were met by profuse apologies and a phrase we came to know all too well -' Doppo domani, doppo domanif' ('perhaps tomorrow, perhaps tomorrow'). I stood one morning looking through the wire of the main gate, when a youngster cautiously approached. In his hand, he held a small loaf of bread, the shape and size of which resembled a large dinner roll. We stared at each other for a moment and then I was overtaken by the temptation of having that bread. Through a series of gesticulations and the surreptitious offer of a ten shilling note, which I had kept hidden on my person, I communicated my message. A rapid exchange took place just in time to avoid the attention of the guard. The boy, in great glee, scuttled off, and I enjoyed that bread, down to the last crumb. Whenever I now set eyes on a similar loaf, that incident leaps to mind.

In their eagerness to make amends, the Italians suddenly introduced, as part of our diet, fresh figs. These were truly magnificent fruit, large, green and luscious. Delicious as they were, however, many of us who were unaccustomed to such excesses found they were a disaster for our innards.

Three or four weeks passed and we were on the move again. During the march to the station, we noticed a strange structure in a public square. It was of light construction, hexagonal in shape, with a door on each side. The importance of this edifice only became apparent when a male entered, quite nonchalantly, and stood, with head and shoulders appearing above the door, and the lower half of his trousered leg visible below the door. As the penny dropped, our column let out loud guffaws. A mixed bag of pedestrians looked puzzled by our laughter.

We detrained at a siding close to the little town of Chieti, west of the port of Pescara. The camp was a far cry from the one we had left at Bari. It consisted of a sturdily-built set of six barracks, which stood on either side of a central macadam road which led from a main gate and office block to the kitchen area. The whole camp was enclosed by a high brick wall. There was no doubt that this was a fairly modern army barracks. The surrounding countryside was hilly and devoted mainly to small farm lots. A short mountain range, the Gran Sasso d'Italia, rising to about 3 000m, stood some 30km away. This mountain range often provided a magnificent display of colour at sunset, a great rose-pink mass poised against a wide sweep of pale green sky.

On arrival at the camp, we found part of it already occupied by other Allied prisoners. The daily routine, as dictated by the Italians, was already well established. A head-count parade was conducted twice each day and the guards wandered at random through the bungalows, keeping their eyes open for any covert activity, such as assembling fake clothing, printing fake documents, or planning an escape. A prisoner's escape committee was already in place, its workings very secretive as there was always the possibility that a spy could be planted among us.

It was also a generally accepted policy that the Italian camp authorities should be psychologically harrassed as much as possible. One prisoner made a successful escape, when, dressed in 'homemade' civilian clothing, he managed to hide in a refuse truck as it was leaving the kitchen. His absence was covered up for a few days and, when it was eventually discovered, the Camp Commandant, predictably, displayed typical Italian volatility. He called for an immediate parade and, accompanied by the whole guard, fully armed, he performed in a most undignified manner. This behaviour, of course, simply further goaded the prisoners.

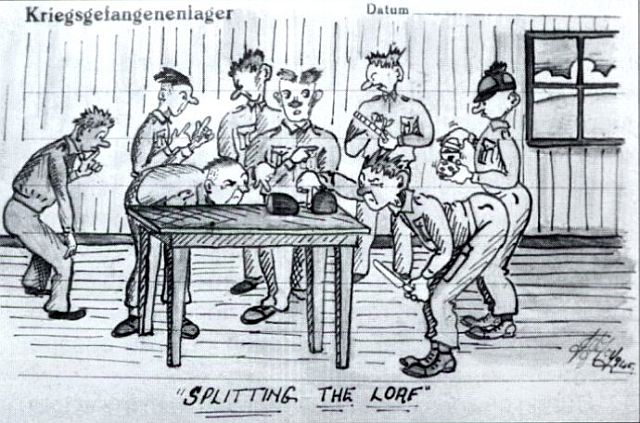

A prisoner-of-war postcard by 'JJF', 01/1945. (By courtesy, SANMMH).

On another occasion, a false map of a proposed tunnel, drawn on a small piece of paper, was folded up and carefully secreted into the joint of a wooden bunk in such a way that a tiny corner of it peeked out. It took about three days before an alert pair of eyes discovered it. Guards, armed with poles, moved slowly through every bungalow, tapping every half-metre or so of flooring in the hope of detecting a hollow sound or loose tile. Many of the prisoners cheekily offered their services, helpfully pointing out quite inaccessible areas for examination. This type of exercise served a purpose - by crowding around a guard, the prisoners were sometimes able to lift the unsuspecting guard's personal documents, which were important for the preparation of false escape papers.

During one of the specious parades, with the whole camp assembled, we witnessed two incidents, one comical and the other a serious indiscretion which might easily have led to tragedy. Opposite our bungalow was one accommodating British officers and, as often happened, we were kept in the hot Mediterranean sunshine, awaiting the arrival of a platoon of guards who were to search the bungalow. Tired of standing, one British officer retired from the ranks, sat down on the ground against the bungalow wall, and withdrew an orange from his pocket. A guard sauntered up to him and told him to rejoin the ranks. The officer ignored the order, whereupon the guard advanced close to him thrusting a fixed bayonet in a menacing attitude. The officer, unable to resist the temptation, coolly planted his orange on the end of the bayonet. The Italian guard was completely dumbfounded as the officer sat smiling up at him. Stalemate! From those who saw the incident, there arose a peal of laughter. At that moment, an Italian officer arrived and the incident was forgotten. Meanwhile, the platoon of guards arrived to commence their search. As the guards marched past the British officers towards the bungalow, one of the prisoners deliberately tripped a guard, who stumbled and fell. The next guard raised his rifle and struck the offender on the head so loudly that everyone on parade heard the 'crack'. Again, the Italian officer in charge managed to restore calm. The prisoners generally agreed that this type of 'joke' was uncalled for, as it posed a threat to life and limb.

Greeting card enclosed in the Red Cross food parcels

distributed to prisoners of war (By courtesy, SANMMH).

It was at the Chieti camp that we first experienced the supply of food parcels, collected, distributed and delivered by the Red Cross. The administration of such a service must have been a monumental task, carried out in the midst of an all-out war. Without the great regard in which the Red Cross was held by all authorities, this important undertaking could not have succeeded. Nor could it have been provided without the considerable generosity of those who contributed the contents of the parcels. As far as we were aware, these parcels originated from two countries - Canada and Britain. Canada, further away from the war zones and therefore not directly threatened, could afford to be more generous in their gifts, and this they certainly were. But to Britain, deeply committed on many fronts, under constant siege from the sea and always open to direct attack, went the greatest respect and thanks from all who received parcels. Each parcel, weighing 10lbs (4,5kg), a neatly packed and sealed cardboard box, was issued to each prisoner at the rate of about one per week. If one multiplies this by the tens of thousands of prisoners scattered over dozens of camps, the immensity of the task becomes apparent. The parcels contained a wide variety of foodstuffs and provided a valuable supplement to the basic fare served in the camps. Furthermore, each parcel represented contact with the world outside the camp. They often contained a tin of jam, egg powder, biscuits, cereal, milk powder, tea, coffee, dried fruit, chocolate and tinned meat.

Most of the prisoners also received a variety of smaller parcels from their families, but, unlike the Red Cross issue, these were always treated with suspicion by the guards, who insisted they be opened in their presence. The guard would carefully inspect each item, socks, underwear, tins of cigarettes and, on each occasion, an expression of envy and resentment would appear on his face. Items such as cakes were cut into pieces to ensure that no maps or compasses were concealed inside them. I recall one parcel of a huge block of chocolate, measuring about 300 x 300 x 50mm, received by a friend. It was the largest mass of chocolate that I had ever seen! The guard's eyes opened wide and, in a fit of envy, he proceeded to break it into a multitude of small pieces which were wrapped roughly and then grudgingly handed over to the owner. With the heterogenous society in the camps, it was not surprising that the businessmen among us separated like cream and quickly established a form of 'swop shop'. These concerns, not exactly non-profit in nature, thrived on the great variety of goods that arrived in the camp as private parcels. Undoubtedly, amongst the most popular items were tins of 50 Players' cigarettes.

While at the Chieti camp, a small group of farmers, British and other, having learned that I held a degree in chemistry, approached me, requesting a short course in chemistry with special reference to farming activities. Without any lecturing experience or reference books, I embarked on the project with some trepidation, having to rely heavily on my memory. Nevertheless, the course must have been a success, judging from the fact that the 'class' increased in size during the few weeks of its duration and, for me, it proved to be a valuable learning experience in the art of 'lecturing'.

After a stay of about a month, we were moved from the Chieti camp, again in first class comfort, to another camp, at Modena, passing through Rimini and Bologna en route. This camp was similar in all respects to the Chieti camp, another soundly built army barracks situated in the rather flat countryside of the Po Valley. As was to be expected, the food was boring, a stodgy pasta with a predominance of tomato. We were grateful for the variety offered by the Red Cross parcels.

The Italian authorities were generous enough to allow us a limited quantity of art material, which enabled a small group of us to gather together and offer our 'works' for criticism and advice from a prominent Cape Town architect amongst us, Capt Brian Mansergh. This activity helped to alleviate some of the frustration and boredom that crept into everyday life and, in a few cases, caused friction among the prisoners. Included in our 'arty' group were a number with considerable talent. One surprised us all. He was Capt Jackie de Jager, a quiet and friendly man of about 35 years of age, who had been a farmer before the war and had admitted to never having put pencil to paper in the artistic sense when he had asked to join the group. After a week or so, he produced several fine drawings. These were sketches of his beloved farming land of which he had so many stories to tell. In due course, he graduated to the use of oils, depicting scenes of the Transvaal with its multitude of umbrella-shaped mimosa trees. His work was outstanding and he received praise from all who saw it.

Weeks passed, months passed, then one morning we awoke to see the camp under a blanket of snow. To many of us, this was a fantasy world, as we had never before been in such close contact with this soft, powdery material. A day or two later, the excitement melted away as did the snow, down our necks and under our clothes as we stood waiting for rollcall in the chilly breeze. Taking advantage of this weather, two South Africans made a bold attempt at escape by sneaking out of the hospital bungalow at 01.00, during a light snowfall. Their escape bid failed and they returned to us after a spell at a punishment camp. They told us how they had both covered themselves in a white sheet and, following a carefully laid out plan, had crawled on their bellies through the snow to a barbed wire fence near the main gate. While the cold weather kept the sentry inside his little box, they cut their way out using a wire-cutter stolen from the camp's maintenance store, and successfully reached the railway station later that morning. With forged papers and posing as Dutch workers returning after leave, they managed to purchase two rail tickets to Milan in the hope of skipping over the border into Switzerland. Their undoing had come when, instead of hiding in the toilets until the arrival of the train to Milan, they confidently strode about the platform, speaking to each other in Afrikaans and buying a newspaper at a kiosk. Shortly afterwards, they were accosted by two men in long, brown overcoats. Their forged papers were examined and a few tricky questions asked. Then they were escorted away for further questioning. It seemed that their answers did not satisfy the two men and their escape bid was brought to an end.

After the Italian Armistice on 8 September 1943, these South Africans successfully made their escape

from POW camps

in Italy and arrived at the POW Commission in Taranto, southern Italy, as free men

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

ITALIAN ARMISTICE, 8 SEPTEMBER 1943

Spring dissolved into a hot, Mediterranean summer. Although we were not aware of it, the months of August and September 1943 had been periods of considerable uncertainty for Italy, culminating in her signing a peace treaty with the Allies. Germany moved troops en masse into northern Italy. For us, it was an ordinary September morning when the SSO was seen striding towards the Camp Commandant's office. There was nothing unusual in that; the two men often conferred and quarrelled over the running of the camp. Then somebody noticed an irregularity. The handful of guards who normally roamed the grounds were absent. The high watchtowers, with machine-guns and searchlights, were unmanned. A strange mood quickly took hold of the camp. Anything portable that would help the prisoners to peer over the high walls of the camp was put to use. Over the wall, an astonishing sight unfolded before the prisoners' eyes. Italian soldiers, in their faded blue uniforms, were vanishing in two's and three's into the field of tall maize that flanked one side of the camp. This extraordinary activity, encouraged by the clapping and cheering of the prisoners - anything for a bit of excitement - continued to the last soldier and concluded with an equally astonishing sight. When the soldiers emerged from the other end of the field, they were dressed in 'civvies'. Seeing this, the prisoners became confused and uncertain. Rumours and speculation swept around the camp: 'Shouldn't we get ourselves out before someone changes their mind?', 'Perhaps this is a trap?' and so on. Eventually the SSO returned and immediately called a meeting. 'I have been advised by the Commandantthat the Italian Government has fallen and that Italy is no longer at war', he reported. Wild cheers and shouting followed. 'Therefore,' he continued, 'We are technically free men.' The prisoners responded with more, louder cheering. The SSO told the prisoners that he had also been advised not to take any hasty action, as there were many German troops in the vicinity and they could be ruthless with a host of escapees roaming loose. The camp was in a state of quiet turmoil, with many prisoners prepared to take a chance and run for it. Most of us packed up our meagre belongings and prepared for any emergency.

The back of this chocolate wrapping was used by a South African POW for study notes (By courtesy, SANMMH).

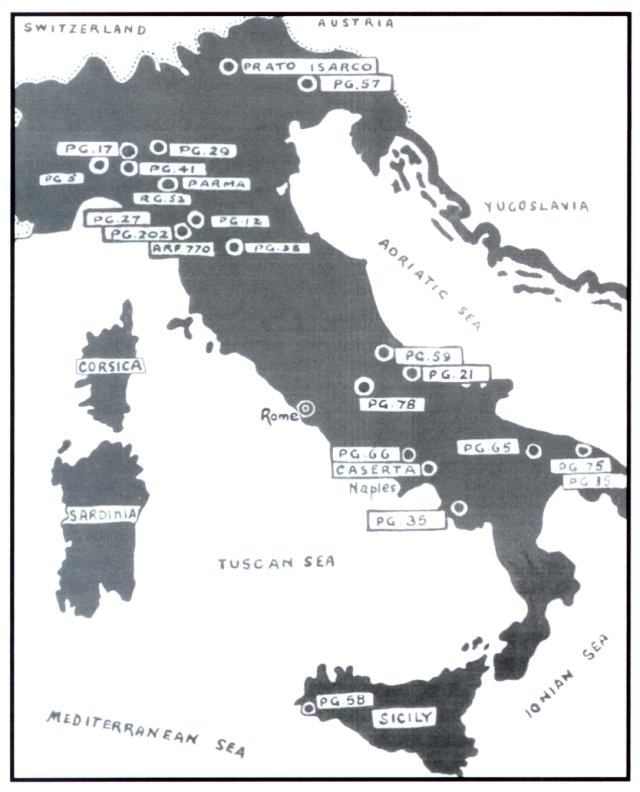

Map of prisoner of war camps in Italy (Courtesy of SANMMH).

Two further events that afternoon compounded an already complex situation. The first happened shortly after noon, when a Roman Catholic priest arrived at the camp gate and, in good English, informed a few officers nearby that British forces had landed, unopposed, at La Spezia, about 100km to the west. 'They should easily reach Modena tomorrow. Be patient, and good luck!', he said. This news, coming from a priest and therefore considered reasonably reliable, stepped up the state of excitement among the men. Opinions and more speculation swept through the camp. The second event that afternoon, also a visitor, who uttered no word, quickly put in doubt any views of an early release. He was an ordinary German soldier, dressed in field-grey and mounted on a much used motorcycle. Over his shoulder was slung his rifle. Not an imposing figure, but nonetheless ominous, threatening. He drove up to the gate, stopped, glanced about the camp and, presumably satisfied with what he saw, turned and drove off. This visit had an electrifying effect on some members, who, ignoring the warnings of the SBO and Camp Commandant, seized their bundles of clothing, raced to the back wall, somehow scrambled over and scattered into the unknown via an adjacent orchard.

Not long afterwards, perhaps an hour and a half, our worst fears materialised in the form of a German unit, bristling with automatic weapons, which burst through the gate and took up positions throughout the camp. An officer appeared at the head of this brisk display of arms and, with the aid of a loud-hailer, informed us that we were now under the control of the German Army. 'You will remain in the camp,' he bellowed, 'It is surrounded and, if necessary, I can call for artillery support.' That was it. We were now Deutsche Kriegsgefangene (German POWs) and faced a very uncertain future. The emotional see-sawing of the day left us drained and unable to think rationally. Satisfied that all was under control, the soldiers left the camp after posting guards.

Under these circumstances, the possibility of unplanned escapes was out of the question, but to some the idea of hiding was an option in view ofthe hint that we would be moved very soon. No head-count had been conducted, so there was no evidence of our precise number. The SBO left the choice to hide to the men, leading to much discussion in the bungalows that evening. Each bungalow, laid out as a large dormitory, was separated from the washroom by a wall about 600mm thick. Access to the washroom was through two doors, one on each side of the wall. Thus, when shut, they enclosed a cavity large enough to hold two men. Several officers decided that this space was to be their place of concealment. Others settled for the ceiling cavity. Both concepts failed, perhaps fortunately. Firstly, the ceilings, which were built of a hollow tile, collapsed under the weight of several men. Secondly, the idea of using the doors was abandoned the following morning, when the entire camp was ordered on parade in preparation for a move. Sensing that there might be dawdlers and others in hiding, German soldiers were sent to conduct a search. They called out, fired one or two warning shots, and then, receiving no reply, riddled the cupboards, doors and any other possible hiding places with automatic fire. This gesture demonstrated the ruthlessness of our new captors.

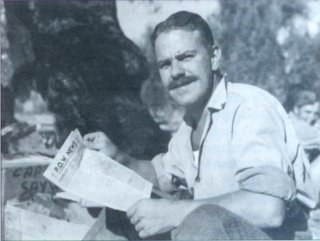

Private John Harding of Johannesburg, captured at Tobruk,

poses with his souvenir copy of a POW newspaper,

after his successful escape bid (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

SS GUARDS

We left our [Italian POW] camp with our little bundles, under the close scrutiny of the guards, marching through the outskirts of Modena to the railway station. It was here that we were reminded once more of the insensitive, brutish manner of the SS (Schutzstaffeln - literally meaning 'protection squads') guards, Himmler's private army. They were entrusted with the duty of looking after prisoners of all categories, including, as we were to learn later, those destined for the concentration camps. This morning one of their number, having transgressed in some way, was ordered by a very young Prussian officer in charge to do press-ups on the gravel platform, in full view of the prisoners. He completed the task in the hot sun and collapsed.

Our train duly arrived, but we were afforded no first class train carriages this time, only dirty old wooden cattle-trucks, interspersed with flat wagons for the guards and their machine-guns, a deterrent for any POW thinking of jumping out. We were divided into groups of 26, each group herded into a truck and the door rolled closed, securely locked and, as we found out later, with the number of prisoners boldly chalked on the outside. I was suffering from a stomach complaint at the time and so crawled into a corner with my possessions to weather out the journey.

Map showing the various POW camps in Germany during the Second World War.

Officers and other ranks were sent to separate Oflag and Stalag camps, respectively

(By courtesy, SANMMH).

We rattled along all afternoon, occasionally catching glimpses of the outside world. It was soon obvious that we were all travelling northwards, passing through Mantova and Verona. Two members of our group guessed that during the night we would be fairly closely to the Swiss border and decided to attempt an escape. The plan was simple but hazardous. They found that a ventilator low down at the end of the truck could be loosened and removed, allowing access to the coupling between the trucks. At about 23.00, they wriggled out onto the coupling, waited for the train to slow down on a corner and leaped into the blackness, while we promptly replaced the ventilator. (About two months later, I received a letter from a friend in South Africa to say that the two escapees were happily living on parole in Switzerland).

In another truck, unbeknown to us, two other POWs were preparing to escape by loosening some floorboards with the purpose of slipping through the gap at the next stop. This stop was at Bolzano, where there was a great rattling of opening doors and shouts of 'Raus! Raus! Austeigen! Austeigen!', ordering everyone out of the trucks. The men clambered out onto the platform in preparation for a head-count. Still feeling unwell, I decided that they could count me in the truck, sitting in my corner, but I misjudged the seriousness with which the guards took their duty. Within moments, half-blinded by torchlight, I was staring at the muzzle of an automatic weapon with shouts of 'Raus! Schnell! Raus!' ('Out! Quick! Out!'). Needless to say, I stumbled out to join my companions on the platform. By that time, the guards and the officer in charge were obviously angry and frustrated. There, before them, the number '26' was clearly displayed on the truck, but they could only find 24 of us. A violent dispute ensued, half in German and half in English, accompanied by wild gesticulations. Finally, reluctantly and without conviction, they accepted that perhaps a mistake had been made at Modena Station. We all climbed aboard again and, at the same time, the second pair of would-be escapees slipped through the gap in the floor of their truck and crawled out. They were spotted by a station official and recaptured amid a second outburst of anger from the guards, who, in their fury, had the two men spreadeagled and tied down with baling wire on a flat truck. They remained in that position until the guard was changed at Innsbruck.

INTO GERMANY - OCTOBER 1943

It was a relief to see that the new guard were not SS troops, but regular German Army troops, not associated with the Nazi Party, but under its control nonetheless. Stopping close to the river, Inn, we were allowed to stretch our legs and snatch a quick wash in the icy water before we received the order, 'Einsteigen! Einsteigen!' and had to clamber on board again. As we clanked along, glimpses caught through chinks in the sides of the truck showed gently rolling farmland with neat, steeply roofed houses. It was calm and beautiful scenery, which made it difficult to imagine that only hundreds of kilometres away, in all directions, the land was shaking with the explosive violence of war. We talked and speculated, not only about our destination, but also our destiny. Somewhere along the way we had been joined by a tall, grey-haired man who spoke English with a half-American, half-German accent. At a later stop, he addressed us with soothing words, telling us that we would be housed in a very comfortable POW camp and that if we behaved well, the Third Reich would respect our rights and our lives would run smoothly. As an experienced propaganda agent, he seemed crestfallen when we received his words with hoots and jeers.

By early afternoon, the train ground to a halt at an unmarked siding opposite which stood a great wooden gate, heavily embroidered with barbed wire. More barbed wire was used to form a high fence on either side of the gate. What lay beyond was obscured by small trees and shrubs. Unbeknown to us, the small town of Moosburg lay one or two kilometres away. Equally unknown, and fortunate indeed for our peace of mind, the town of Dachau was only 50km away, to the south-west. (This small German town was destined to become notorious as the site of one of the most hideous extermination camps dotted like festering sores over the Nazi fatherland).

We passed through the wooden gate with some trepidation as recent pre-war history had shown the German hierarchy to be a group of ruthless men, capable of unscrupulous acts, and we were now entirely in their hands. From the gate, we entered a large wooden building. Here we were given precise instructions in gutteral English: 'Strip. Put your belongings and clothes in neat piles. Shower. Then get dressed.' This done, we moved into an unbelievably large camp with hundreds of dark, wooden huts arranged down each side of a wide, macadam road. Groups of these dwellings were enclosed by barbed wire fences and occupied by a huge variety of disheveled-looking men. Scattered amongst this motley crowd were disinterested-looking German guards, some with rifles slung casually over their shoulders, others holding Alsatian dogs on long leads. The mood of the camp seemed to be one of complete dejection and hopelessness. After being ushered into one of these encampments, and having selected our wooden bunks with their straw mattresses, we were left to contemplate the depressing situation.

There were many thousands of prisoners, of almost every Allied nationality, in the camp; the majority appeared to be French, most of whom had been there since the early days of the war. This long term of residency bestowed upon them the right to carry out the daily running of the camp under mild supervision by the German authorities. The greater one's store of cigarettes or other items of value, the greater one's ability to purchase a variety of goods and services. For example, it was said that hunting knives could be obtained, that a pistol and ammunition could be bought forthe 'right price', and that a few tins of cigarettes could buy a night out in Munich, only 50km away. Most of the prisoners of the camp were other ranks and were sent out in work parties during the day. They were not slow to learn how to appropriate items of food and clothing during these outings. The most degrading facility provided at the camp was a long, narrow and deep trench with three stout poles supported above it. This trench, built in the open, was one of several toilets, capable of serving ten men at a time. But it required a monumental urge to visit this public area and an even greater concentration to maintain one's balance while inhaling the appalling fumes of chlorine, etc, that clung to the area.

Complaints directed to the camp authorities by our group's SBO quickly elicited an explanation of why we were there. Apparently, our permanent camp was not ready, but we were due to leave for it in a few days' time.

We were soon on our way again, this time in drizzling rain, marching a great distance along country lanes through two villages with long, unpronounceable names, and ending at a huge railway marshalling yard. Here, wet, tired and cold, we were given what we came to learn was coffee, a brew made, as one prisoner quipped, from the sweepings of the forest. In fact, it was probably made from a roasted acorns. Into the cattle-trucks again and later that day we passed through a city which someone recognised as Ulm. It was clear that we were moving westwards and the following day we arrived at Strasbourg. It must have been as great a surprise to the townspeople as it was to us when we were led from the station, across the street and into a line of empty trams! This extraordinary convoy set off through part of the city, then, unexpectedly, into the country, our journey ending at a terminus in a small forest. Alighting, we passed through the woods and arrived at a bridge leading across a deep, dry moat and via an iron-barred door, into a massive concrete structure, most of which was set below ground level. Always conscious that our future was fraught with uncertainty, this new destination seemed ominous. Our concern grew when we were ushered down a long, poorly-lit concrete staircase and into the bowels of the edifice. We came to learn a little while later that this was a fort dating back to the Franco-Prussian War and it was to be yet another stop on our protracted journey to a permanent camp. We exercised by walking back and forth along the length of the moat floor, some eight metres below ground level, while the guards paced along the lip of this trench.

Among the prisoners was a canny Scot who, in some inexplicable manner had managed to carry his bagpipes all the way from North Africa! At sunset on fine evenings, he set himself at one end of the moat and played his pipes while most of the others were exercising. The strange skirling tunes of 'Coming thro' the Rye', 'Hielan' laddie' and so forth fascinated the German guards. So fascinated were they that, drawn as if by magnet, they gradually forsook their posts and gathered above and near the source of the sound. Two prisoners, probably British and fluent in French, took note of the guards' movements over several days and used this to formulate their plan of escape. On a suitable evening, with the permission of the escape committee, they scrambled up the deteriorating wall furthest from the musical Scot and vanished into the dusk. Two days later, the German guards discovered their absence and the Commandant, in true German style, called a parade, increased the guard, and burst into a cold rage. His language, colourful German, was understood by only a few, but we got the point. Obviously, his pride was wounded, but he realised that the Geneva Convention forbade him from taking any action against us. It was our good luck that we were not in the hands of the SS!

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org