The South African

The South African

About the authors

Filip Debergh is a teacher at St Leocollege in Bruges, Belgium, and is involved in the exchange programme between his school and Hoerskool Waterkloof, Pretoria. He is a First World War guide in the Ypres battlefield area, who has developed a particular interest in the role of the South Africans in the First World War. Jaco van Wyk is a teacher at Hoerskool Waterkloof, Pretoria, South Africa.

Springbok head emblem.

On 20 September 1917 at 05.40, two regiments, the 3rd and the 4th South African Infantry battalions of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade, left their assembly positions and advanced from Frezenberg Ridge in the direction of Zonnebeke. Zonnebeke is a small village 8km to the east of Ypres, the town that all soldiers who fought in Flanders knew so well. The attack was later officially named the 'Battle of the Menin Road' and was part of the so-called 'Third Ypres Offensive' in 1917. The South Africans achieved their objective, but the toll was considerable: Of the 2 576 men who went into battle, 1 255 were reported killed, wounded or missing. Today, ninety years after the battle, the date 20 September 1917 appears all too often under the laurelled Springbok head emblem, with its motto 'Union is strength - Eendracht maakt macht', on the headstones of the South African war graves.

Filip Debergh

20 September 2007

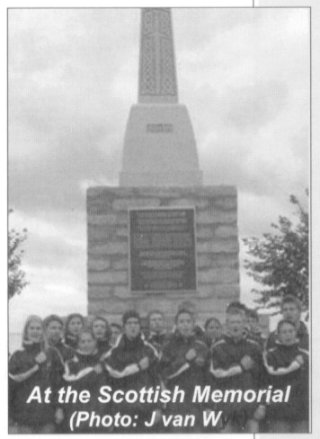

Pupils of Hoerskool Waterkloof, Pretoria, gathered around the brand-new Scottish Memorial on the Frezenberg Ridge near Zonnebeke exactly 90 years after the attack there by the South African Infantry Brigade. They have come to Belgium annually for the past ten years as part of an exchange program with St Leocollege in Bruges.

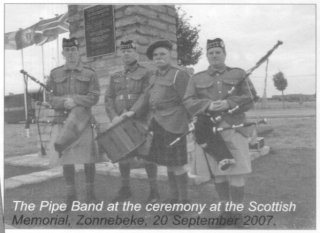

At 15.00 three pipers of the Passchendaele 1917 Pipes and Drums Band played the tune, 'Road to Passchendaele'. The bandsmen of this recently-raised band play in service dress, which was the daily uniform of the Scottish soldiers in the Great War. This was a uniform that must have been quite familiar to the men of the South African Scottish, the 4th Battalion of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade who, no doubt, on many occasions marched towards the front line accompanied by the regimental band playing the 'Atholl Highlander' march and other Highland songs.

The pipe band at the ceremony at the Scottish Memorial,

Zonnebek, 20 September 2007.(Photo: F Debergh)

The Mayor of Zonnebeke, Mr Dirk Cardoen, welcomed the pupils and expressed his gratitude to the South African Brigade who had fought for the village of Zonnebeke and, in doing so, for the liberation of Belgium. Quoting the words of historian Richard Holmes, he said: 'I cannot think of ground more unlike the familiar veld or Drakensberg, although the language would have made sense to many of them', referring to the similarity between Flemish and Afrikaans. More than 15% of the South African ranks in 1917 were Afrikaans-speaking. Many had names like Van Niekerk, Van Blerk, Vanderiet or Morgendaal. The Mayor ended his speech in Afrikaans by saying: 'Ons sal vandag hulde bring aan al die Suid-Afrikaners. Ons sal die jong seuns van Suid-Afrika nie vergeet nie' ('Today we pay homage to all the South Africans. We will never forget the young men of South Africa').

Battlefield guide, Filip Debergh, then explained what had happened on that infamous day in 1917. The battle took place in a small area which is visible, in its entirety, from the Scottish Memorial today. It seems remarkable that, in 1917, it took three hours to reach an objective that now involves a ten minute walk. It is difficult to imagine the apocalyptic scenery of ninety years ago, which transformed a pastoral haven into a hellish wasteland. Major C M Murray of the South African Field Ambulance described the area as 'surpassing the gloomy descriptions we had already had ... Shell-holes filled with water and evilsmelling slime. So long had the fighting been going on here, that the face of the earth was blasted and upheaved beyond description.' Jay Winter in Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History writes that it must have been 'an otherworldly landscape, where the bizarre mixture of putrefaction and ammunition, the presence of the dead among the living, suggested that the demonic and satanic realms were indeed here on earth.'

The area around the monument is undoubtedly still a vast tomb for the missing. Of the ninety South Africans buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery, only a handful are identified. The others remain in the churned-up soil of Flanders. Recent archaeological excavations in Boezinge and Zonnebeke have yielded human remains of First World War soldiers and here, in some cases, the detailed analysis of bones and other remains by forensic pathologists has led to identification and a reburial ceremony ninety years after the battle in the presence of family members. No South African remains or artefacts have been excavated yet, though there were recent digging activities near the Terca Brickworks, where the Bremen Redoubt, a German dug-out, was discovered in 1983. Bremen Redoubt was one of the main objectives of the South African Infantry Brigade and they actually captured the stronghold on 20 September.

A more recent discovery between Borry Farm and the Hanebeek revealed a German dug-out and an underground tunnel system. The material harvest consisted of German equipment, bottles of wine and an intact pocket watch. This reminds one that the vast number of battalions that fed the war machine consisted of individual human beings, each with his own personal history. This was highlighted at the ceremony, when the South African learners read out three individual stories of South African soldiers who died or were wounded on 20 September 1917. One of these soldiers, David Schalke Ross, was not yet 14 years old when he was hit by a bullet in his leg. Three small crosses were placed at the foot of the monument to commemorate these young men.

At the ceremony, Melissa Smit, one of the Waterkloof learners, thanked the Belgian government for keeping the remembrance alive and for donating the cemetery grounds for perpetuity. She expressed the hope that warmongers might reflect upon the futility of war and that war has never ended a war (see p41). After the exhortation and the laying of wreaths, the Waterkloof learners sang the South African National Anthem. With the flag of the 'rainbow nation' fluttering in the wind, one wondered what the Springbok soldiers would think about the South African teenagers bringing honour to them exactly ninety years after they lost their lives here.

After a visit to Caterpillar Crater near Hill 60 (one of nineteen craters resulting from the intensive mining operation on 7 June 1917, which blew the Germans off their positions on the Wijtschate-Mesen Ridge) and after a walk through the German trench system of Bayernwald near Wijtschate, the learners arrived at the Menin Gate in Ypres. Designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and built by the British government, the Menin Gate Memorial was opened on 24 July 1927 as a monument to the missing British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the fierce battles in the Ypres Salient area and who have no known grave. On two central pillars, the names of the missing South Africans are inscribed. Every evening at 20.00, buglers from the local fire brigade close the road that passes under the Memorial and play the 'Last Post'. In front of a large audience, the Waterkloof learners, visibly impressed by the occasion, laid a weath under the side gallery and, moments after the 'Last Post' and 'Reveille', the South African National Anthem resounded under the Memorial. Against protocol, people started to applaud and the pupils were congratulated by the members of the Last Post Committee. Some of them have promised to return in 2017 for the centenary commemoration.

Scottish Memorial in Flanders

The Scottish Memorial in the vicinity of Frezenberg, Zonnebeke, was unveiled on 25 August 2007. The choice of the location for a national Scottish monument could not have been better. The monument was erected on the edge of the area where the Scottish 15th Division launched a bloody attack on 17 August 1917 and offers an impressive view of the battlefield where that action took place. Only weeks later, the 9th Scottish Division, with the 1st South African Brigade under command, took over the sector and were involved in the Battle of the Menin Road on 20 September. Not far from the monument is the hamlet of Potijze. Apart from a chateau, there was an advanced dressing station there, where many wounded Scottish and South African soldiers received first aid in the aftermath of these futile attempts to force a breakthrough.

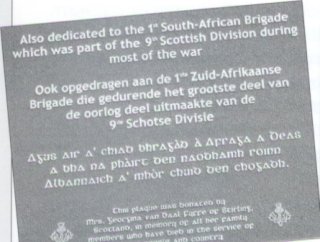

The monument was financed by a variety of sponsors, ranging from regimental associations, local councils, societies, government executives and individuals. A bronze plaque on the back of the monument was donated by Mrs Georgina van Daal Fyffe of Stirling, Scotland, in memory of all her family members who have died in the service oftheir people and country. This plaque is also dedicated to the 1st South African Brigade.

The brass plaque in memory of the South African Brigade

(Photo: F Debergh)

The monument is a 3-metre high 'High Cross' or 'Celtic Cross' of Scottish granite, set on a plinth of orginal bunker stones. ('High Crosses' are part of an age-old Celtic tradition and were erected in many places in the United Kingdom and Ireland to commemorate war casualties. Both in shape and material, they are largely inspired by the local village monuments one finds all over Scotland.)

At the Scottish Memorial (Photo: J van Wyk).

For the past ten years, Hoerskool Waterkloof in Pretoria has had an exchange programme with St Leocollege in Bruges, Belgium. During this three-week visit by twenty learners and two teachers, one full day is normally spent visiting the First World War battlefields near Ypres in Flanders, Belgium, with Filip Debergh, a teacher of St Leocollege. During the First World War, six million shells hit Ypres and nothing was left standing.

'The Battle of the Mud', 3rd Ypres Offensive

This year's exchange programme was unique. It was exactly 90 years ago that South African soldiers were involved in the battle of the Menin Road, part of the Third Ypres Offensive, on 20 September 1917, sustaining heavy casualties. The Third Ypres Offensive is commonly known as the 'Battle of Passchendaele'. Lloyd George, British Prime Minister at the time, referred to it as 'the Battle of the Mud'. Unfortunately for the Allies, it was the wettest summer the area had ever seen and the disaster cost 250 000 lives on the Allied side alone, 35 soldiers per yard (0,914m) of territory won. Tiny Passchendaele itself was hit by a million shells.

German cemetery

A visit was also paid to the German Studentenfriedhof near the village of Langemark. This cemetery, with its rows of black headstones interspersed with clusters of moss-covered stone crosses, is the resting place of more than 44 000 German soldiers, many of them young students who fell in the First Battle of Ypres. Looking at a mass grave of 25 000 soldiers, the young South Africans realised the price paid for their respective countries by the young men on both sides.

In the trenches at Bayernwald (Photo: Jaco van Wyk).

Tyne Cot Cemetery

The visit to Tyne Cot Cemetery was breathtaking, firstly in respect of the size of the cemetery and, secondly, in respect of the number of tourists. Many of the tourists were supporters of the Rugby World Cup in France, who had taken a day to visit the Flanders battlefields. Most were from the British Isles, Australia and New Zealand. In the cemetery, the Springbok head emblem appeared on row upon row of pristine white headstones, indicating ninety South African graves amongst the almost 12 000 soldiers who had been buried there. The date of death of many of the South Africans was the same 20 September 1917. Re-burials continue today and remains are still excavated nearby and identified. The saddest thing about the Tyne Cot Cemetery, however, is the 35 000 soldiers who have no known grave and whose names are engraved on the Memorial to the Missing, a semicircular wall.

Tyne Cot Cemetery (Photo: Jaco van Wyk).

Museum experience

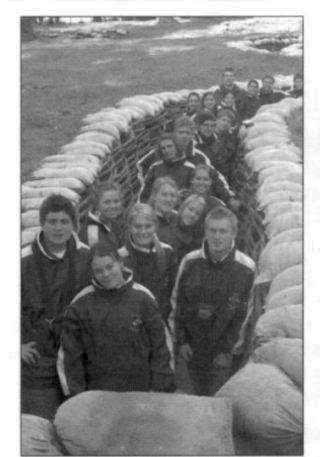

After Tyne Cot, there was the visit to the Memorial Museum Passchendaele at Zonnebeke. The South African learners experienced something new here - in fairly bad weather, standing in a queue to enter a museum. The displays in the gas section, describing the various types of gas and gas-masks and very realistic artificial walk-through trenches, with the sound of guns, were some of the highlights. When one imagines this, and the smell and wetness of the mud, one realises the nightmare that these soldiers must have experienced in those trenches.

A highlight of the tour was

the gas warfare exhibit at the

Memorial Museum Passchendaele.

(Photo: J van Wyk).

Commemoration of the South Africans in the Battle of the Menin Road

The next stop was the commemoration ceremony at the new Scottish Memorial at

Frezenberg. The 1st South African Brigade was part of the 9th Scottish Division,

which is commemorated at this memorial. At the ceremony, the Mayor of Zonnebeke,

Mr Dirk Cardoen, thanked South Africa for her part in the War and Filip Debergh

gave a lecture on South African involvement.

Three Hoerskool Waterkloof learners, Riaan Becker, Kim Ludick and Bernard

Maritz, read out the personal stories of three individual South African

soldiers. Melissa Smit gave an overview of the war and Ruan Kleynhans read out

the fourth stanza of Laurence Binyon's poem, 'For the Fallen'.

The speeches were in Dutch, Afrikaans and English. Three other learners,

Lara Coetzee, Antonie Manser and Tineil Hurter, laid a wreath at the memorial.

About 50 people attended the commemoration. Among them were Richard Jones, who

now lives in England, dressed in the uniform of the Transvaal Scottish

Regiment, the Passchendaele 1917 Pipes & Drums Band, and Ivan Sinnaeve, better

known as 'Shrapnel Charlie'. Ivan is famous for the toy soldiers he makes from

First World War shrapnel. A local television station recorded the commemoration

and later presented it on the news bulletin with an extended interview with one

of the learners, Tanya van Wyk. Het Nieuwsblad newspaper also published

a report and a photograph of the commemoration.

Hill 60 and Bayernwald

The learners also visited the huge Caterpillar Crater at Hill 60, the site of the most violent explosion before the dropping of the first atom bomb on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. The visit to the German trench system at Bayernwald was also an interesting outing.

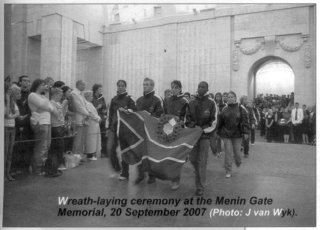

Ceremony at the Menin Gate

The highlight of the day was the wreath-laying ceremony at Menin Gate, Ypres. The Menin Gate was completed in 1927. The names of 54 896 British and Commonwealth troops who had been lost in the quagmire of the trenches up until 15 August 1917, and who therefore had no graves, are inscribed on this huge, white gate. Here, the Hoerskool Waterkloof contingent was part of the official delegation to lay wreaths. The Master of Ceremonies sketched the background to what happened on 20 September 1917 and referred particularly to the South African involvement on that day. The uniformly dressed Waterkloof school group walked over the Meensesstraat (Menin Road) as part of the commemoration and three learners, Pieter Brits, Lesetja Madiba and Marli du Toit, climbed the steps to lay the wreath.

Under the Menin Gate, the school also had the opportunity to sing the South African National Anthem, which sounded magnificent, causing the hundreds of spectators gathered there to break into spontaneous applause, many with tears in their eyes. The rendering of the 'Last Post' was also memorable, especially when one is reminded that, with the exception of the days under German occupation during the Second World War, it has been played every evening at 20.00, since 1928. These days the Ypres Fire Brigade is responsible for playing the 'Last Post'. After the ceremony, many people came to talk to the South Africans and thanked them for their participation in the ceremony, the singing of the anthem and their good behaviour. They mentioned relatives living in South Africa, visits to the country and their appreciation of the fact that young people from South Africa still commemorate their country's fallen comrades from the First World War.

Wreath-laying ceremony at the Menin Gate Memorial, 20 September 2007 (Photo: J van Wyk).

Lessons

The experience was very rewarding and emotional. The Canadian, New Zealand and Australian governments were notable for their deep involvement in this year's commemoration events, especially those of the Battle of Passchendaele. The South African learners on the tour wondered what our own government was doing, especially in terms of the approaching centenary of the First World War. Surprised that they had not learnt about the involvement of South African soldiers in this War and about the huge loss of life during the conflict, the learners thought that such information ought to be included in the school curriculi. They felt that the South African government had a responsibility to inform people about the First World War and to support these commemoration ceremonies financially, especially as the centenary of the war begins in seven years. They also believed that people needed to be reminded of the price these men had paid and that it should serve as a reminder that war must be avoided at all possible costs.

Acknowledgements

The learners and teachers wish to thank Dr L C Becker, the Executive Headmaster of Hoerskool Waterkloof, and the school's Governing Body, for the opportunity to experience this enriching exchange programme. St Leocollege and its teachers, especially Carline Vanderschelden, Peter Waes and Filip Debergh, and the parents and learners were wonderful hosts. A word of special thanks goes to Carolien Verster for her magnificent organisation during this exchange programme.

When the 1st South African Infantry Brigade launched their attack in the vicinity of Zonnebeke, early in the morning on 20 September 1917, in what was later officially called 'the Battle of the Menin Road', their war record was already quite impressive. The brigade had been raised and trained in Potchefstroom in August 1915 to serve overseas. A lot of the 'boys' had already been involved in the South West Africa campaign in what is now Namibia but was then a German protectorate.

The brigade consisted of four regiments. The first regiment was raised mainly in the Cape; the second, in Natal and the Orange Free State; the third in the Transvaal; and the fourth regiment consisted of boys of Scottish origin from all regions. The 4th SAI were suitably named the 'South African Scottish' or the 'kilted Springboks'. In September 1915, 160 officers and 5648 ranks left the Cape by transport ships and, after their arrival in England, they were moved to Bordon Camp, South Hampshire, for training. From December to February 1916, they operated in Egypt to protect the vital supply and communication route provided by the Suez Canal. After the Egyptian campaign, the Brigade arrived at the harbour of Marseilles in the south of France and were transported to Armentieres in the north, where they prepared forthe big Somme offensive in July 1916. They were attached to the 9th Scottish Division.

On 14 July 1916, the Brigade entered Delville Wood and were ordered to hold it at all costs. Under constant artillery and machine-gun fire and surrounded on three sides, the South Africans fought without relief for five days. Only 768 men of the 3 153 who entered the Wood answered the roll call after the battle. Today, the Wood is the location of the South African National Monument near Longueval.

In April 1917, the brigade was involved in a poorly prepared action to capture the village of Fampoux, near Arras and, after this fiasco, the men cynically called themselves 'the Suicide Springboks'. At the end of the battle of the Somme, companies of South African infantrymen were used as mass burial parties, which also dampened their morale. Fortunately, the brigade commander was Henry Timson Lukin, an Anglo-Boer War veteran, veteran of the South West Africa campaign and survivor of Delville Wood. We know that Lukin refused to wear a gas-mask when inspecting the ranks in the front line. He also stepped aside to let troops pass along the duck-boards. The South African Brigade prepared itself for action again, this time for the big Flanders Offensive in the summer of 1917. On 12 September it left Achiet-le-Petit in the north of France and arrived at Poperinghe, a town 10km behind the Ypres front line, on 15 September. After detraining in the town of Ieper, the brigade headed for the deep dug-outs near the Boezinge Canal. Accompanied by guides, the men were funnelled along duck-board- covered ground and reached the assembly positions in darkness. The landscape ahead was disenchanting: derelict tanks, muddy shell holes, not a blade of green grass and, everywhere, well hidden in the churned-up soil, German pillboxes with machine-gun nests that would have to be captured, one by one. Even locating the starting positions in the darkness was a tough task, though the areas were marked with white tape and signposts.

The main objective of the battle of the Menin Road was the capture of the strategically important Geluveld Plateau, a task assigned to the Second Army under General Plumer, who had achieved a major success in capturing the Mesen-Wijtschate Ridge in early June. Further north, the Fifth Army under General Gough tried to break through the Wilhelmstellung, the third defensive line of the Germans. To the left and the right of the Ieper- Roeselare Railway, the 9th Scottish Division was deployed, with the South African Brigade on the left.

In the beginning of August, a massive attack along a wide front had proved to be a tactical failure. Haig now decided in favour of the 'bite and hold' tactic, involving attacks along a much smaller front with limited objectives that had to be taken, step by step. Massive artillery support had to squash the inevitable enemy counter-attacks. Along a front line of less than 10km, the Second and Fifth armies had 875 pieces of heavy artillery and 1 320 pieces of field artillery at their disposal.

The task for the South African Brigade was far from easy. The troops had to advance 1,5km from Frezenberg and reach a line beyond Bremen Redoubt. At the end of August and early September, this terrain had already been captured a number of times by British battalions, but had to be conceded each time after counter-attacks. Names such as 'Beck House', 'Borry Farm', 'Vampir Farm' and 'Potsdam' had a negative association among experienced soldiers in the sector.

At 05.40 on 20 September, the attack was launched. After a preliminary artillery barrage, the 4rd and 3rd SAI advanced behind a smoke curtain and a creeping barrage. They successfully reached their objective, the Red Line, capturing Beck House, Borry Farm, Mitchell Farm and Vampir Farm. The troops displayed great courage by not just running behind the creeping barrage, but actually risking jinking through it, surprising the Germans who did not have the time to get out of their pillboxes to put their machine-guns on the roofs.

Even so, losses were substantial as the 3rd SAI ran into enfilading fire from Potsdam Reboubt, a stronghold consisting of three bunkers. When this stronghold was eventually captured, it was difficult to restrain the men from shooting the enemy as they came out.

An hour later, the second stage of the attack began. On the right, the 1st SAI had to 'leapfrog' the 3rd SAI to reach the Green Line. The 2nd SAI had to 'leapfrog' the 4th SAI and advanced towards Bremen Redoubt. The 2nd SAI came under enfilading fire from Hill 37 and Tulip Cottages. In the meantime, the terrain became a quagmire, with men struggling waist deep in the mud. It was during this second stage in the battle that L/Cpl William Henry Hewitt captured a pillbox single-handedly. He threw a grenade into a doorway, but the Germans threw a stick-bomb that blew off Hewitt's gas-mask and knocked out four of his teeth. Furious because he was engaged to be married and now feared that his fiancee might no longer find him attractive, Hewitt reached the rear of the pillbox. He tried to lob a bomb through a loophole, but missed and had to dive for cover. With only one bomb remaining, Hewitt crept right up to the loophole and, from beneath it, pushed the grenade through, receiving a shot in his hand as he did so. He eventually succeeded in arresting a number of Germans. Fifteen others lay dead in the pillbox. For his exploits, Hewitt received the Victoria Cross, the highest British award for gallantry.

The South African Brigade reached all its objectives, but at a considerable cost. On most of the headstones of the South African graves, there is only one date, 20 September 1917. On the night of 21 September, the South Africans were relieved by other units. Joe Samuels, a veteran, remembered: 'We stuck it out, although with no time to do anything at all for those who were drowning or being cut up. We were played out and should've been finished had we been left there any longer. How we longed for the heat and dusty landscape of Southern Africa.'

The Brigade was in action again on 12 October, during the first battle of Passchendaele. In 1918, during the German Spring Offensive, they were engaged in the battle for Messines on 10 April. There was hardly anybody left from the original contingent that had left Cape Town in 1915.

Bibliography

Bostyn, Franky, Passchendaele 1917 - The story of the fallen and Tyne

Cot Cemetery (Roularta Books, 2007).

Buchan, John, The South African Forces in France (London, Edinburgh

and New York, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1920).

Digby, Peter, Pyramids and Poppies - the 1st SA Infantry Brigade in

Libya, France and Flanders 1915-1919 (Rivonia, Ashanti, 1993).

Liddle, H Peter, Passchendaele in perspective - the Third Battle of Ypres (London, Leo Cooper, 1997).

South Africa and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (Berkshire, CWGC).

Spagnoly, T and Smith, T, Salient Points Three (South Yorkshire, Leo Cooper, 2001).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org