The South African

The South African

On 3 November 1873, a short, confused skirmish took place in the heart of the Drakensberg between Chief Langalibalele's amaHlubi warriors and a small Colonial column under Major Antony Durnford. From a military point of view, it was a trifling affair, but it was nevertheless to have far-reaching repercussions, both for the amaHlubi and for the young colony of Natal. This amaHlubi Colonial forces clash, which took place at Bushman's River Pass near Giant's Castle, is also of interest from the point of view of Durnford himself, given the important role he would play in the much more well-known black/white showdown at Isandlwana a few years later, in 1879. Durnford's distinguished, if often controversial, military career has been admirably addressed in these pages by Steve Bourquin, 'Col A W Durnford' in Military History Journal, Vol 6, No 5, June 1985. This article will provide a more detailed focus on the Bushman's River Pass engagement itself, based on the first-hand accounts of some of those who had the dubious privilege of being caught up in it.

Maj A W Durnford, who led the march

against Langalibalele (Photo: SANMMH).

The trouble with Chief Langalibalele of the amaHlubi, nicknamed 'Long Belly' by the British, began when the Resident Magistrate of Estcourt, J MacFarlane, ordered him to comply with the terms of the Gun Law by having all firearms in his people's possession sent in for registration. Langalibalele failed to comply, reluctant to press his subjects to surrender their hard-won weapons, even for a temporary period. Many believed that it was all a ploy to disarm them and, in practice, it indeed happened that guns brought in were retained indefinitely or rendered useless before return. Had the Natal authorities been less heavy-handed and the amaHlubi less panicky, the controversy need not have got out of hand. Instead, the initial incident led to a rapid deterioration of relations between the two, causing a chain reaction of accumulated misunderstandings that left each party convinced that the other was intent on war.

Losing patience with the recalcitrant Langalibalele, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Benjamin Pine eventually decided to mobilise a large force to bring him to heel. This force comprised the Pietermaritzburg and Karkloof Troops of the Natal Carbineers, two companies of the Gordon Highlanders, the Richmond Mounted Rifles and some 8 000 Natal Native Levies. Langalibalele's response was to retreat to the relative safety of the southern Drakensberg passes, accompanied by his warriors and his people's cattle. His flight was considered an act of secession and was therefore treasonable.

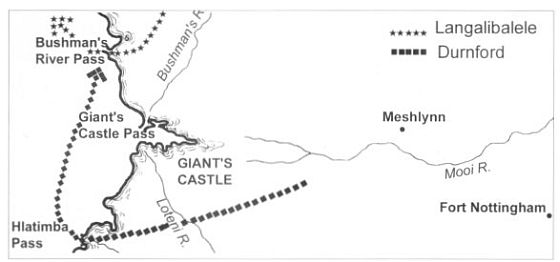

To prevent the amaHlubi from leaving Natal, Pine decided to detach part of the Natal force and use it to turn them back at the Bushman's River Pass, near Giant's Castle. The Karkloof Troop under Captain Barter received their orders to turn out on 31 October. The next day, they mustered at Fort Nottingham where they were joined by the Pietermaritzburg contingent. The combined force was made up of 55 white troopers (including two officers and six NCOs), 25 mounted baSotho auxiliaries and a baSotho interpreter, Elijah Kambule. Maj (later Col) A W Durnford of the Royal Engineers was in overall command. Born in Ireland in 1830 and a professional soldier since the age of sixteen, he had arrived in South Africa in 1871 and been transferred to Natal a few months previously.

Chief Langalibalele.

On Sunday, 2 November, Durnford and his 80 mounted troops set out from Fort Nottingham to intercept Langalibalele. Simultaneously, Border Agent CaptainAllison and 500 black auxiliaries were instructed to ascend via the 'Champagne Castle Pass' and then proceed southwards along the escarpment to link up with Durnford at the head of the Bushman's River Pass early on the following Monday morning. As subsequent events were to prove, it was an absurdly simplistic and over-optimistic plan, casually conceived as if all that was required was a canter over a few undemanding hills. Negotiating the mighty ramparts of the Drakensberg was not a job to be undertaken lightly under any circumstances. To expect Durnford's men to proceed all the way from Fort Nottingham to one of its highest summits in a mere ten hours or so was unrealistic, to say the least. Military Intelligence had also done a poor job of reconnoitring the country, with the result that Allison never made it to the summit at all. (It might have helped had 'Champagne Castle Pass' actually existed). Durnford, meanwhile, took the wrong route and reached their objective a full day later than was intended. Had he known that the planned rendezvous with Allison would not take place, he almost certainly would have abandoned the expedition. Durnford's expedition started to go wrong almost from the outset. The night was foggy, with the result that those in charge of the pack horses, lagging in the rear, lost their way in the gloom, depriving the column of most of its supplies and much of its ammunition.' The baSotho men were asked to share their rations, which they did willingly. Morale remained high, despite this setback, It was already clear that this was not a routine patrol and the largely untried volunteers were eagerly anticipating their first taste of combat.

At daybreak on 3 November, the column advanced up the Game Pass, a spur of the main range. From there, they had a clear view of the Bushman's River Pass leading up to Basutoland (present-day Lesotho) and of amaHlubi herdsmen driving cattle up the steep, rocky slopes. It was then that the men strayed off course. Instead of attempting to ascend via Giant's Castle, they proceeded up the Hlatimba Pass, some ten kilometres further south. The Hlatimba route, apart from its extra distance, entailed a nightmarish trek through some of the most difficult terrain in the country, a veritable maze of deeply cut valleys, cliffs and ridges calculated to daunt even the staunchest of mountaineers. Even so, for all its difficulties, it was at least passable - just - for mounted men. This was certainly not the case with the precipitous slopes leading up Giant's Castle. The exhausting day-long climb, which began at daybreak and continued until well into the night, effectively crippled the Carbineers as an effective fighting force long before the first shot was fired. Even those who managed to struggle through to the summit were to be too wretched and exhausted to be of much use. During the ascent, Durnford's horse, Chieftan, lost his footing and dragged his master over a steep incline. As a result, he fell about fifty metres, 'head over heels, like a ball', breaking two ribs, dislocating his left shoulder and sustaining severe lacerations. Chieftan, by remarkable chance, escaped largely unscathed. Badly shaken and in considerable pain, Durnford would have been justified in handing over command to someone else at this point, but he decided to press on. Some of his men, overcome with exhaustion, were unable to match his soldierly stoicism and dropped out, one by one, as the day progressed. Those who persevered made a pitiful sight as they clambered, yard by yard, up the forbidding mountainside, leading their horses and frequently slipping as they sought to avoid colliding with them. Trooper Henry Bucknall later recalled how he and his comrades were able to cover no more than twenty to thirty metres at a time before being forced to rest. Durnford's second-in-command, Captain Barter, more advanced in years than the men under him, was reduced to crawling and had to be helped along. He later described the spectacular but wild and forbidding nature they encountered: 'The scene before us was savage in the extreme. Down the bare side of the Mountain hung ribands of water, showing the spot to be the very birthplace and nursery of rivers; above, huge krantzes frowned, while the masses of unburnt dry grass, hanging like a vast curtain, gave a sombre and malignant aspect to the scene.'

Map showing the route taken by Maj Durnford's column

in the hope of blocking the escape of Langalibalele's amaHlubi.

Hungry, exhausted and dispirited, the remaining 32 men who eventually reached the head of the pass were in no state to fight a battle the next morning. Too cold to get much sleep, they off-saddled and waited wretchedly for morning, smoking their pipes in lieu of dinner. Durnford, his left arm in a sling, had understandably lagged far behind the rest of the horsemen, fainting away completely at one point. Without the attentions of Trooper R H Erskine, who loyally attended to his stricken commander throughout the day, he would never have made it to the summit. It was only at 03.00 on Tuesday that he finally caught up with the column.

It was soon reported to Durnford that Langalibalele had already succeeded in escaping into Basutoland, but that many of his people had yet to cross the border. Durnford had no intention of allowing them to do so. There was no sign of Captain Allison, only thousands of head of cattle attended by about a hundred young amaHlubi herdsmen. Durnford strung his tiny force in a long line across the mouth ofthe pass, dismounted and at intervals of six paces, and gave strict instructions not to fire unless confronted with an overt act of aggression. In this, he was only following the instructions of his superior, Lieutenant-Governor Pine. Many embittered troopers strongly criticised the order afterwards, claiming that, had they been given a freer hand from the outset, things might have turned out differently.

If Durnford's intention in deploying his men in an extended line had been to stage a show of strength, he failed. Instead, the thin line showed the amaHlubi, who were making their way up the slopes, how few white men there were against them and their confidence grew as the morning wore on. Since the troops were ravenous by then, Barter ordered one of the Hlubi animals to be slaughtered. Durnford insisted that the animal be stabbed rather than shot, as he was afraid of the potential effect of a gunshot on the bristling tribesmen. A farcical scene ensued, at the end ofwhich a cow was finally dispatched, but the watching amaHlubi had probably become even more agitated from watching the melee than they would have been, had the animal been simply shot. Some of the Karkloof men, for reasons best known to themselves, then dissuaded Durnford from paying for the kill, something that would have gone a long way towards appeasing its owners. So famished were the troops that several ate their meat raw.

At 08.00, some mounted black troops appeared near the summit of the pass. Thinking that they might be Allison's men, Durnford, accompanied by some of the baSotho auxiliaries and the interpreter Kambule, rode up to them. A long parley ensued between him and Mabuhe, commander of Langalibalele's forces. It was a tense time for all concerned, but especially for the straggling band of inexperienced Colonial troopers exposed on the mountainside. By then, scores of amaHlubi were streaming up the slopes and lining the rocks on either side of their pitifully thin line. Those who had firearms - a not inconsiderable number - sighted them at the troopers at little more than 80 yards (73m) range and waited. Others climbed to the rear of the column, completely surrounding them. Under these circumstances, Durnford's orders to turn back any amaHlubi moving up the pass looked increasingly ludicrous. Before long, the latter began to push their way past the Carbineers on their way to the summit, ignoring any feeble attempts to stop them. Those on the flanks became progressively more menacing, ostentatiously sharpening their assegais on the rocks or jeering at the nervous troopers, telling them to bring out their real army.

By 09.00, 400 to 500 amaHlubi were positioned around the head of the pass and at least half of them carried firearms of some sort. Even seasoned professional troops would have been hard-put to maintain their discipline under such circumstances. Many had lost faith in Durnford, who seemed oblivious of the fact that the situation was on such a knife-edge and that, at any moment, the amaHlubi might rush down and annihilate them. Certainly, Kambule had no doubts on that score. He practically begged Durnford to allow his men to open fire, but Durnford was determined to stick to the letter of his directive not to fire the first shot.

Group of colonials of the Richmond Mounted Rifles,

c1872 (Photo: SANMMH).

The behaviour of Sergeant Clarke, the Carbineers' drill instructor, helped to turn the uneasiness into mutinous panic. As a veteran of the Eighth Frontier War and a long-serving regular soldier, it had been hoped that his experience and age would serve to stiffen the resolve of the men of the column. Instead, he began to shout, at the top of his voice, that they were all about to be murdered. He would be severely censured for this 'shameful and mutinous' conduct, in the words of Lieut-Governor Pine. His defence would be that he had only been trying to show his obstinate commander how perilous their position had become.

Sensing that his men were on the point of breaking, Durnford called out dramatically, 'Will no-one stand by me?' Three of the troopers, Erskine, C D Potterill and E Bond, responded, rallying to his side. He then gave the order for a slow withdrawal to higher ground and the men, forming fours, moved off at a walk towards the gully through which they had entered. They did so in fairly good order, considering how jaded and scared they were at this stage, but matters had already gone too far.

"'Whiz" came a bullet,' recalled Trooper H Bucknall, 'Then they poured in thick like the pattering of a hailstorm.' There was no thought of answering the fusillade. Durnford turned to see his men disappearing at a gallop around the shoulder of a stony hill, the orderly retreat instantly transformed into a rout. Durnford's men now had to run the gauntlet of at least 200 muskets fired at them at close range while their tired horses attempted to negotiate the treacherous slopes. The flanking hills were wreathed in smoke and swarming with excited amaHlubi warriors running back and forth to get a clearer shot. Their firearms were too antiquated and their marksmanship too poor for them to do much damage, but the skirmish was destined to claim a few lives before it was over. The first to fall was the gallant Trooper Erskine, followed soon afterwards by Bond and by Katana, one of the baSotho levies. Potterill was next. One of the amaHlubi later recalled seeing him, dismounted and possibly already wounded, being pursued by three warriors. He managed to shoot one of his assailants before the other two caught and dispatched him.

Durnford nearly shared the fate of the three loyal young men who had answered his call for support and had paid for it with their lives. He had hung back to allow Kambule, whose horse had been wounded by an assegai thrust, to mount behind him and this delay enabled two warriors to rush in and seize Chieftan's bridle. Before he could draw his pistol and shoot them, Durnford received two assegai wounds, one through his already injured left arm that severed a nerve and left the limb permanently disabled. Kambule was killed in the flurry, shot through the head. All that Durnford could do was to follow the retreating horsemen down the gully, which he did, almost weeping with rage and frustration. He recalled how, at the time, his main concern was not so much to ride free as it was to shoot his cowardly men when he caught up with them. Sergeant Varty also had a narrow escape during the retreat. His own horse was shot and he was only able to cover another hundred metres or so on Erskine's horse, which Trooper R Spiers had been able to catch for him as it careered down the slopes, saddle turned almost under its belly, before it was also wounded. Fortunately, Durnford's spare charger was available. While Sgt Varty was getting it under control and remounting, under heavy fire, several of his comrades hung back to support him.

Headdress badge, Natal Carbineers

The Carbineers were thoroughly shown up by the mounted baSotho auxiliaries who, rallied by their young chief, covered their precipitous retreat and kept the amaHlubi at bay. Durnford tried to rally the Carbineers, but they broke again as soon as the first pursuing amaHlubi came into view and did not stop until they reached the camp. The miserable drill instructor, Sergeant Clarke, led the way, thereby putting the seal on his ignominious day's performance. The amaHlubi followed on foot for as long as they could down the Hlatimba Pass until their quarry were finally out of range and then returned in triumph, singing their war song.

Durnford and his ragged force returned to Fort Nottingham on 5 November, three days after their departure. Their arrival sparked a bitter furore of recriminations, accusations and counter-accusations that would take a considerable time to die down. Few emerged with much credit from the whole fiasco and at least one career - that of Sergeant Clarke - was ruined because of it. Clarke tried in vain to clear his name, writing a series of letters to the local newspapers and beseeching, without success, the Natal Governmentto institute a commission of enquiry. Later, when he was dismissed from the army altogether, he chose to leave Natal rather than be identified forever as a coward. Two weeks after the abortive expedition, Durnford, accompanied by some men of the 75th Regiment and several hundred mounted levies, returned to Bushman's River Pass to bury the five men who had fallen in the skirmish. Cairns at the top of the pass - now known as the Langalibalele Pass - mark their graves and climbers in the area will be familiar with the adjacent peaks that today bear their names: Erskine, Bond, Potterill, Kambula and Katana. For good measure, there is also a Mount Durnford and a Carbineer Point.

Durnford's career survived the debacle, although he, too, came in for much criticism. In particular, he was accused of having ignored the advice of the Colonials, who, after all, knew the country and its people better than he did. Judging by the accounts of some of those who had served under him, Durnford does appear to have been profoundly out of touch with the feelings of the amaHlubi and of his own troops. His blunt assertions that the Carbineers had failed in their duty further enraged the colonial population, who took this as a slur against the local militia. Someone even went as far as to poison his dog. Nevertheless, on 11 Dece:mber, Durnford was promoted to lieutenant-colonel, a vindication of his personal performance in the otherwise disastrous affair. The final chapter in this gallant soldier's career - and the one for which he is primarily remembered - would be written a few years later on the blood-soaked field of Isandlwana. For Langalibalele, the story does not have a happy ending. Four flying columns were organised to capture him and, on 11 December, coincidentally, the day on which his adversary was promoted, he was handed over by the baSotho chief, Molapo. Following a mockery of a trial in Pietermaritzburg, he was sentenced to banishment for life. He returned in 1887, after the British Government intervened on his behalf, and died two years later. The amaHlubi also paid dearly for their defiance. Over a hundred were killed in a series of punitive attacks and their land and cattle were confiscated by the Natal Government.

Further Reading

Bourquin, S, 'Col A W Durnford' in Military History Journal, Vol 6, No 5, June 1985.

Durnford, E, A Soldier's Life and Work in South Africa, 1872-1879: A Memoir of the Late A W

Durnford (London, 1882).

Pearse, R O, et al (eds), Langalibalele and the Natal Carbineers - The Story of the Langalibalele

Rebellion, 1873 (Ladysmith Historical Society, 1973).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org